Recent advances in hierarchical heterostructures and mechanical properties of additively manufactured aluminum alloys

Abstract

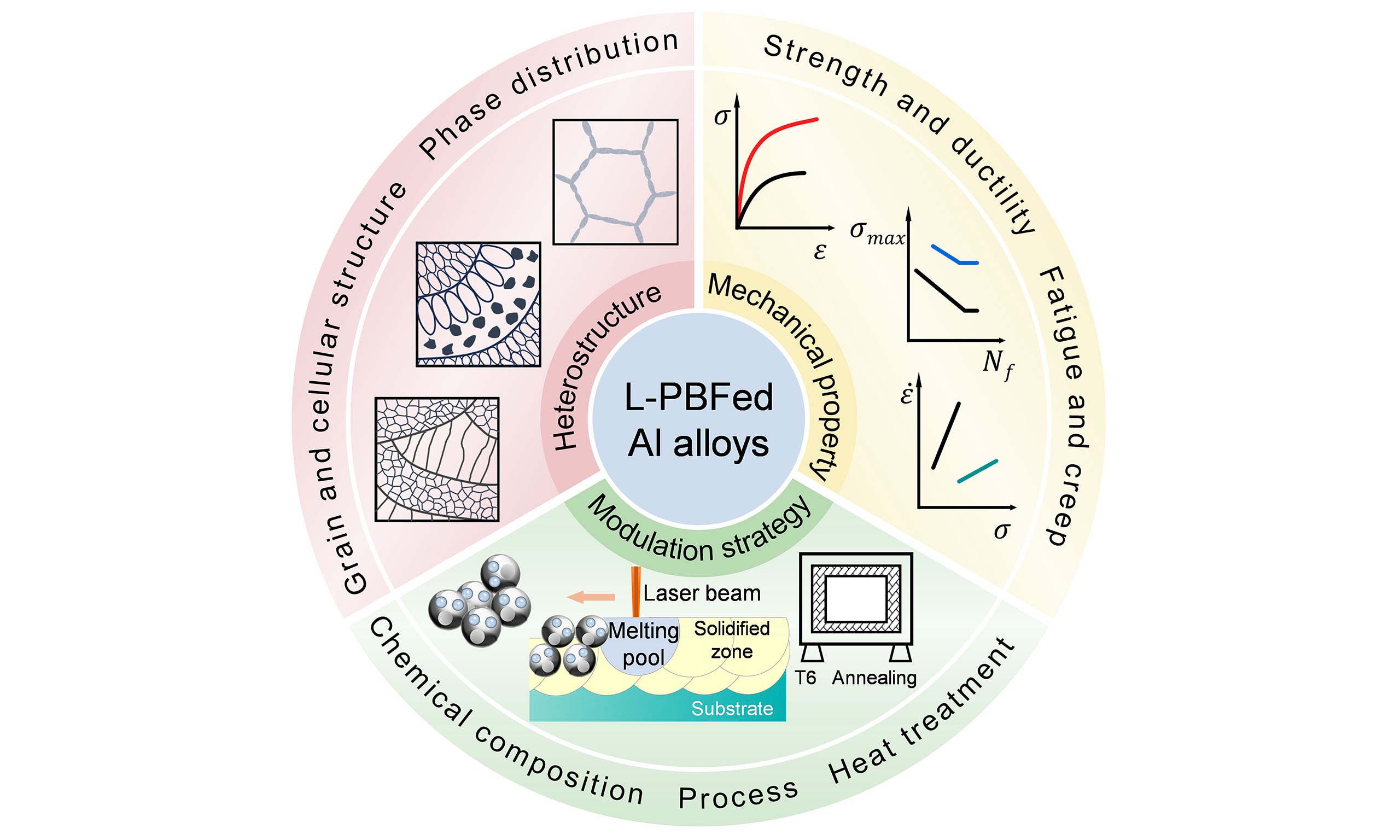

Driven by the rapid advancement of key engineering domains such as aerospace, transportation, and marine systems, there is an urgent need for aluminum alloys exhibiting superior mechanical properties. Heterostructures, defined by inhomogeneous distributions of microstructural domains with distinct property gradients, have become a leading strategy to achieve a synergy between outstanding strength and satisfactory ductility. Additive manufacturing technologies, particularly laser powder bed fusion (L-PBF), provide unparalleled design flexibility for creating heterogeneous microstructures. This review systematically classifies the various heterostructures in additively manufactured aluminum alloys, investigates the mechanisms enabling precise control of microstructural heterogeneity, and underscores the exceptional mechanical performance of L-PBF-processed alloys with such structures. Moreover, the challenges and opportunities associated with advancing heterostructured aluminum alloys via L-PBF are critically analyzed, highlighting the necessity for robust theoretical frameworks and scalable manufacturing approaches.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

Due to their favorable combination of specific strength, specific stiffness, and corrosion resistance, Al alloys have become pivotal in advancing sustainable lightweighting for engineering industries, driven by continuous improvements in comprehensive service performance[1,2]. As critical physical properties for structural materials, strength and ductility are generally targeted for synergistic optimization, representing a central goal of material design and modification[3,4]. Nevertheless, the persistent strength-ductility trade-off in Al alloys remains a critical bottleneck, impeding breakthroughs in mechanical properties and restricting their broader engineering applications[5,6].

This challenge has motivated researchers to explore innovative microstructural designs, such as heterostructured materials, drawing inspiration from natural systems like bamboo, teeth, and mollusk shells[7]. These materials exhibit superior mechanical properties and application potential compared to homogeneous counterparts, establishing themselves as a vital class of engineered systems[8]. Heterostructured materials, typically composed of two or more domains with distinctive differences in chemical composition, microstructure features, and properties, can be classified into several categories, including gradient structure[9], lamellar structure[10], core-shell structure[11], bimodal structure[12], dual-phase structure[13], and metal matrix composites[14]. It is gradually recognized that heterogeneous materials, comprising soft and hard domains distinguished by their structural and/or mechanical features, develop extra strengthening and strain hardening that surpasses the predictions by the rule of mixtures[15,16]. During the initial stage of deformation, the hard domains remain primarily elastic, while the soft domains preferentially undergo plastic strain[17]. Due to the strain gradients induced by strain partitioning arising from mechanical incompatibility, geometrically necessary dislocations (GNDs) are generated and pile up against the domain boundaries[18]. This results in forward stress within the hard domains and back stress within the soft domains[19,20], thereby significantly elevating the yield strength of heterostructured materials[21]. As plastic deformation progresses into the hard domains with increasing strain, the accumulation of GNDs near the domain boundaries accommodates hetero-deformation, which in turn further enhances work hardening capability[22]. Notably, the synergistic interaction between back stress and forward stress contributes to both hetero-deformation induced (HDI) strengthening and strain hardening[23].

In pursuit of superior comprehensive performance in Al alloys, considerable research efforts have been dedicated to designing microstructural heterogeneity[24]. For instance, gradient structures are characterized by spatially varying grain sizes or particle densities, such as dual-gradient Al alloys produced via short-flow thermomechanical processing (SFTP), which achieve balanced strength-formability through surface-to-center gradients in precipitates and grain size[25,26]. Furthermore, methods like friction stir processing (FSP) have demonstrated the potential of gradient heterostructures by introducing Fe-Al compounds and pseudo-precipitate gradients, achieving strength-ductility synergy[27]. Despite these advancements, the scalability of such heterostructured materials remains limited by the complexity of their fabrication processes, necessitating further exploration of production efficiency for industrial applications.

The emergence of additive manufacturing (AM) has revolutionized the fabrication of heterostructured Al alloys[28-30]. Laser powder bed fusion (L-PBF) technique, a prominent AM technique, stands out for its ability to produce near-net-shape components with complex geometries through layer-by-layer selective melting of metal powders[31-33]. By reducing the reliance on post-processing methods common in traditional machining, L-PBF has become an industry-standard technology[34]. Owing to rapid heating and cooling rates, as well as complex thermal gradients, the microstructures of Al alloys produced by L-PBF are unique compared to those obtained via casting, powder metallurgy, or other techniques[35,36]. The Gaussian energy distribution of the laser spot leads to distinct solidification conditions across different regions of the entire melt pool[37,38]. Furthermore, various solutes in Al alloys exhibit distinct solidification behaviors under rapid solidification, such as dendrite growth and segregation[39,40]. These characteristics, combined with the diverse family of Al alloys and the intricate interplay between laser parameters and powder composition, enable precise regulation over microstructural heterogeneity[41-43].

This review systematically addresses the following aspects of heterostructured Al alloys produced via L-PBF: (1) microstructural heterogeneity and formation mechanisms - analyzing the origin of HDI strengthening and domain boundary interactions; (2) critical influencing factors - establishing correlations between processing parameters, heterostructure evolution, and mechanical performance; and (3) future perspectives - proposing strategies for scalable fabrication and property enhancement. By elucidating the structural characteristics, modulation techniques, and performance responses of heterostructured Al alloys, this work aims to provide deeper insights into L-PBFed materials and accelerate the development of next-generation high-performance alloys.

HETEROGENEOUS MICROSTRUCTURES

In general, the intrinsic distribution differences in solidification features during the L-PBF process, including complex thermal gradient and rapid cooling rate, can lead to hierarchically multiscale heterostructures within Al alloys. The appropriate introduction of distinct solute elements, coupled with the solidification conditions afforded by AM, results in microstructural heterogeneity, which primarily manifests through the heterogeneity of grain structure, cellular structure, and phase distribution. It is worth noting that as research on materials deepens, various heterogeneous structures simultaneously arise in the AM of Al alloys. A fundamental elucidation of the morphology characteristics and formation mechanism of diverse heterogeneous microstructures is crucial for the design of additively manufactured Al alloys. The following sections will review reported works on each type of heterostructure.

Heterogeneity in grain structure

To date, wrought Al alloys have garnered significant attention for L-PBF due to their outperforming specific strength and remarkable precipitation hardening response. However, age-hardenable Al alloys, represented by Al2024 (Al-Cu), Al6061 (Al-Mg-Si) and Al7075 (Al-Zn-Mg), exhibit a high susceptibility to hot cracking, potentially compromising their printability and deteriorating mechanical properties. This vulnerability stems from their wide solidification temperature range and complex thermal history inherent in the L-PBF process. It is well recognized that the incorporation of alloying elements (Sc, Zr, Ti, Nb, etc.) can mitigate the aforementioned intricacy, resulting in the successful fabrication of highly dense and crack-free components[44-54]. Consequently, a wide category of Al alloys, such as Al-Mg-Sc-Zr[44,45], Al-Mg-Si-Sc-Zr[46-48], and Al-Zn-Mg-Cu-Nb[49,55], have emerged as high-performance Al alloys tailored for L-PBF.

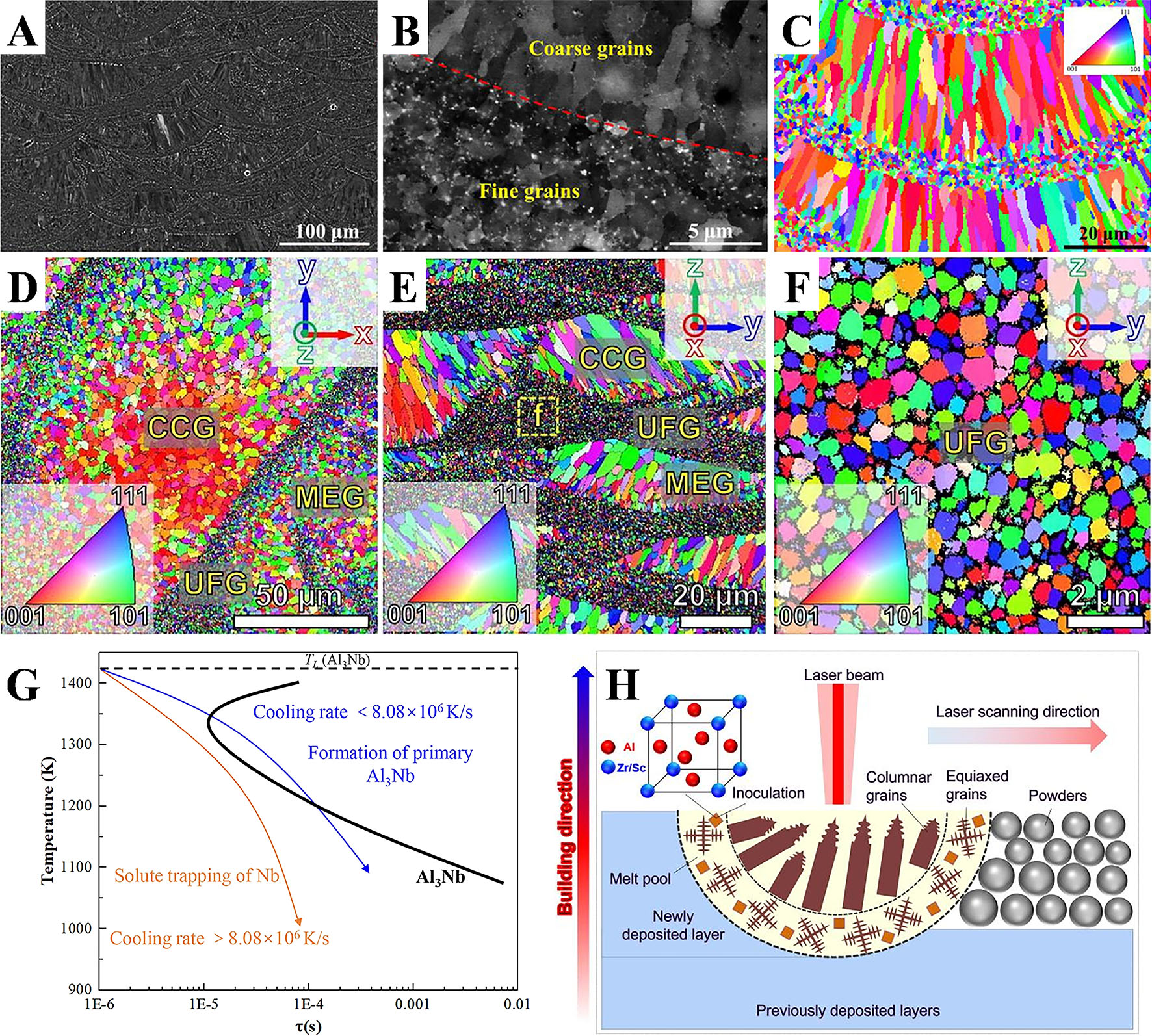

From the crystallographic perspective, the L12-structured Al3X (X = Sc, Zr, Ti, Nb, etc.) phases precipitated within the melt pool can serve as appropriate inoculants for the heterogeneous nucleation of α-Al matrix, ultimately promoting the formation of equiaxed grains. The substantial difference in solidification-front velocity between the edge and top of the melt pool can lead to uneven precipitation behavior of Al3X phases, resulting in a heterogeneous microstructure characterized by bimodal or multimodal grain structures. For instance, Wang et al. reported a heterogeneous grain structure in crack-free L-PBFed Al-Mg-Sc-Zr alloy, consisting of ultrafine grains (UFGs) with random orientations and coarse-grained domains exhibiting a strong <001> solidification texture[44], as shown in Figure 1A-C. The strain partitioning between UFG bands and coarse-grained domains is considered the primary mechanism for additional back stress hardening, improving strain hardening ability and enhancing mechanical properties. Similarly, Zhu et al. fabricated crack-free AlZnMgCuScZr alloys with an unprecedented strength-ductility synergy[50], revealing a multimodal grain size distribution with periodic building blocks composed of coarse columnar grains (CCGs), medium-sized equiaxed grains (MEGs), and UFGs [Figure 1D-F]. Specifically, UFGs with an average grain size of approximately 350 nm are observed along the melt pool boundaries, separated by MEGs with grain sizes ranging from 2 to 8 μm and CCGs with widths of approximately 2 μm and lengths ranging from 3 to 20 μm. The high grain boundary density induced by effective grain refinement disrupts thermal stress and bolsters crack resistance, thus suppressing the generation of defects during L-PBF. It should be noted that the Al alloys modified by alloying elements accommodate stress associated with solidification instead of shifting the solidification behavior, to attain the elimination of cracks[56,57].

Figure 1. Heterogeneous microstructures induced by grain structure. (A and B) Backscattered electron (BSE) images along deposition direction of L-PBFed Al-Mg-Sc-Zr alloy; (C) Inverse polar figure (IPF) map[44]. (D and E) IPF images observed from the top surface and side view of the L-PBFed AlZnMgCuScZr alloy showing the heterogeneous grain distribution; (F) IPF image revealing the UFGs[50]. (G) Calculated incubation time for the competing Al3Nb primary phase and Al matrix, with two cooling curves representative for the center (orange curve) and the bottom (blue curve) of melt pools in the L-PBFed Al-Zn-Mg-Cu-Nb alloy[49]. (H) Schematic sketch of the L-PBF process for AlZnMgCuScZr alloy[50].

It is well-known that the heterogeneous grain structure is primarily related to the distribution characteristics of primary Al3X particles. Therefore, understanding the formation mechanism of precipitation behavior under complex conditions is essential for tuning microstructural heterogeneity. The energy density distribution of the laser heat source in L-PBF commonly follows an axisymmetric Gaussian profile, leading to variations in thermal histories across different regions of the molten pool during the interaction between the laser beam and the powder[58,59]. Meanwhile, the rapid movement of the high-power laser beam and the transient ultra-high temperature within the melt pool contribute to an extremely fast cooling rate up to

Heterogeneity in cellular structure

The eutectic Al alloys, with a narrow solidification temperature range, exhibit enhanced printability and reduced hot cracking during the rapid solidification process of L-PBF. A distinctive cellular structure, comprising supersaturated α-Al cells and a eutectic network along cell boundaries, is commonly observed in additively manufactured eutectic Al alloys, a consequence of localized compositional variations. The layer-by-layer cyclic heating and cooling characteristic of L-PBF not only melts the current powder layer but also partially remelts previously solidified layers, resulting in a heterogeneous cellular structure.

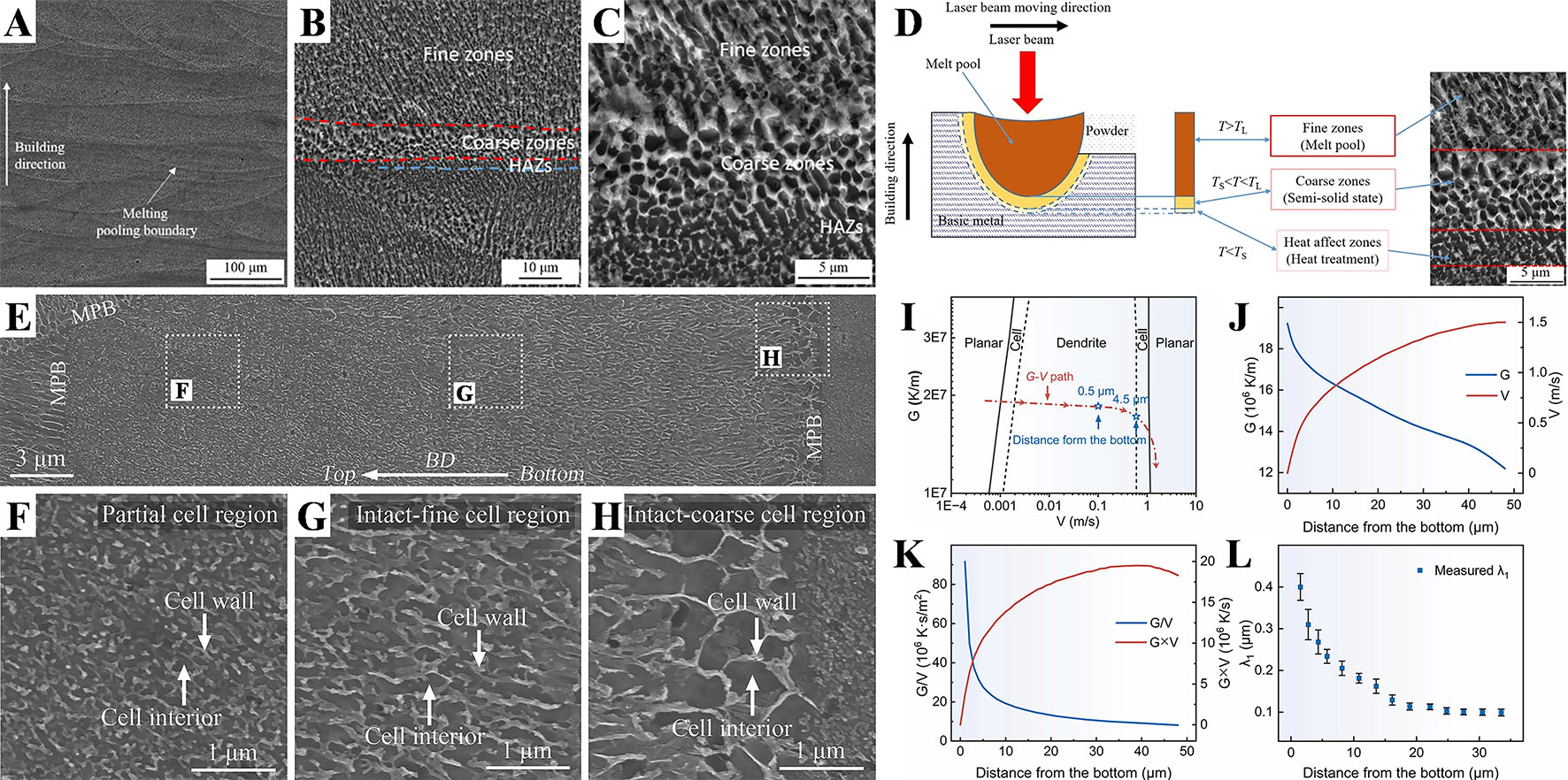

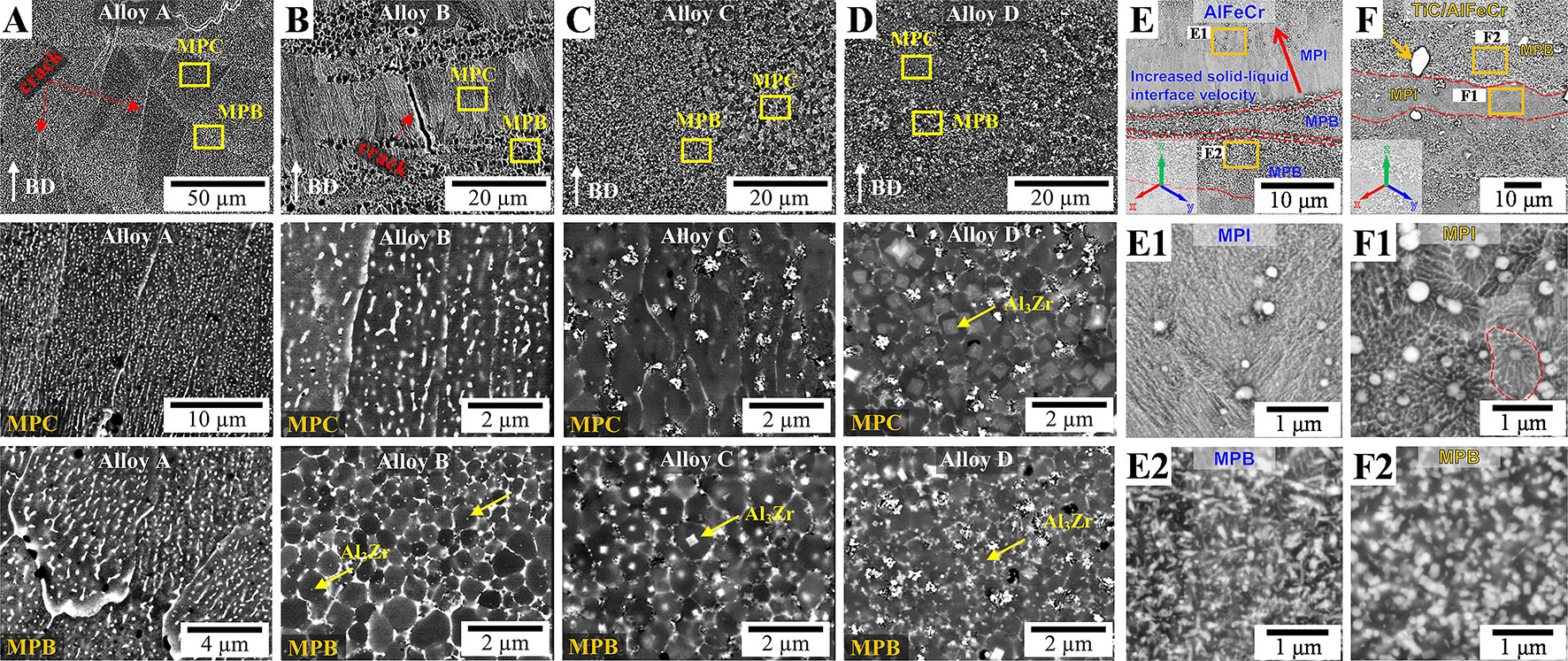

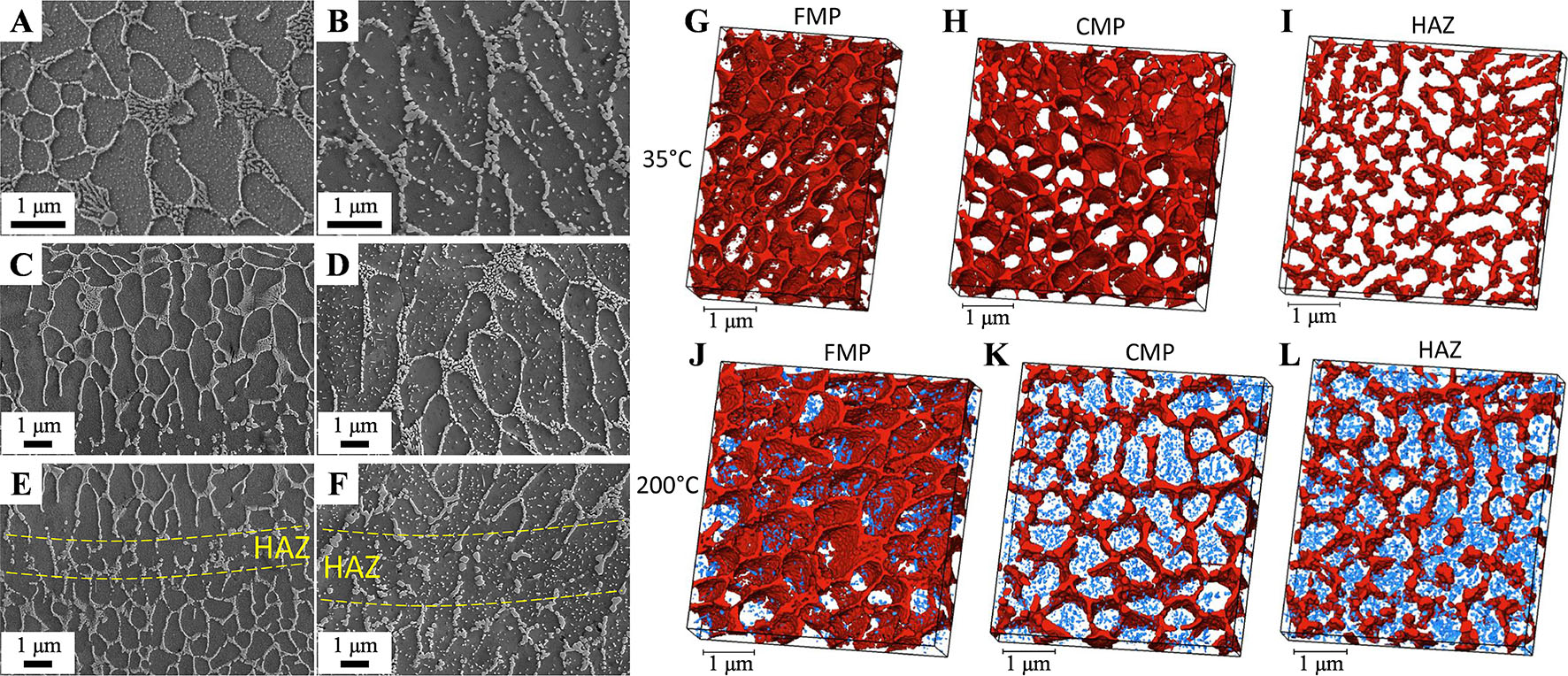

Among castable Al-Si alloys, AlSi10Mg has emerged as a potential candidate in the nascent stage of AM development, owing to its broad applications in aerospace and electric automotive industries[61-63]. The cellular structure observed in L-PBFed AlSi10Mg alloy exhibits three distinguishable zones, including fine zone, coarse zone, and heat-affected zone (HAZ), which is differentiated by the morphology and size of the Al-Si cellular structure[61] [Figure 2A-C]. The fine zone and coarse zone are also referred to as fine melt pool (FMP) zone and coarse melt pool (CMP) zone, respectively[62]. The Si-rich eutectic phase within the FMP and CMP manifests as a continuous and interconnected cellular structure, but becomes fragmented and spheroidized in the HAZ. Furthermore, the FMP, dominated by columnar α-Al cells, typically constitutes the majority of the melt pool, while the CMP, containing equiaxed α-Al cells, exists at the melt pool border in association with HAZ. As depicted in Figure 2D, this microstructural heterogeneity in L-PBFed AlSi10Mg alloy arises from temperature gradients induced during laser beam heating[61]. Compared to conventional powder metallurgy and cast methods, the unique cellular structure and dispersed Si precipitates in AlSi10Mg promote a pronounced Orowan strengthening effect[64,65]. However, the relatively low spheroidization temperature of the Si phase leads to decomposition of the continuous Si-rich cellular boundaries into submicron Si particles during prolonged thermal exposure, thereby restricting the high-temperature application of AlSi10Mg[66].

Figure 2. Heterogeneous microstructures induced by cellular structure. (A-C) Microstructural characterization on the longitudinal cross sections in L-PBFed AlSi10Mg; (D) Schematic diagram of the formation mechanism for microstructure heterogeneity in the L-PBFed AlSi10Mg[61]. (E) SEM image showing multiple cellular structures across the whole melt pool in the L-PBFed Al-Ni-Sc-Zr alloy; (F-H) Magnified images of the white squares indicated by the dashed lines in (E); (I) Microstructure selection map of Al-5.6Ni alloy (wt.%) with the red line referring to the solidification path of L-PBFed Al-Ni-Sc-Zr alloy; (J) Variations of temperature gradient (G) and solidification velocity (V) at the solidification interface; (K) Curves depicting G × V and G/V within the melt pool; (L) Experimentally measured cell spacing (λ1)[67].

Recently, novel eutectic Al alloys containing principal alloying elements such as Ni, Fe, Ce and La have garnered substantial attention in L-PBF[67-70]. The low equilibrium solubility and limited diffusion coefficient of such elements in the α-Al matrix promote the formation of thermally stable cellular structures, leading to excellent elevated-temperature mechanical properties. For example, Luo et al. utilized L-PBF to prepare an Al-Ni-Sc-Zr alloy with multiple cellular structures composed of Al cell interior and Al9Ni2 cell wall[67]. The alloy maintained a yield strength of 203 MPa at 300 °C, attributed to the continuous and integral cell walls. It is noteworthy that the intact-coarse, intact-fine, and partial cell regions can be categorized along the building direction (BD), as illustrated in Figure 2E-H. The potential mechanism underlying the cellular structure heterogeneity throughout the melt pool can be elucidated by classical solidification theory, considering the temperature gradient (G) and solidification velocity (V) [Figure 2I-L]. The G/V ratio dictates the solidification morphology, whereas the product of G and V (G × V) is pivotal in determining cell size. A rapid reduction in the value of the G/V ratio favors the transition from dendritic to cellular morphology, thus promoting cellular structure formation. Meanwhile, the size of the cellular structure, which is related to an opposite correlation with the value of G × V, represents a decreasing cell size gradient from the bottom to the top of the melt pool. Additionally, the rejection of Ni solute at the solidification front also influences the morphological characteristics of the cell wall, leading to the intact and partial Al9Ni2 cell wall.

Heterogeneity in phase distribution

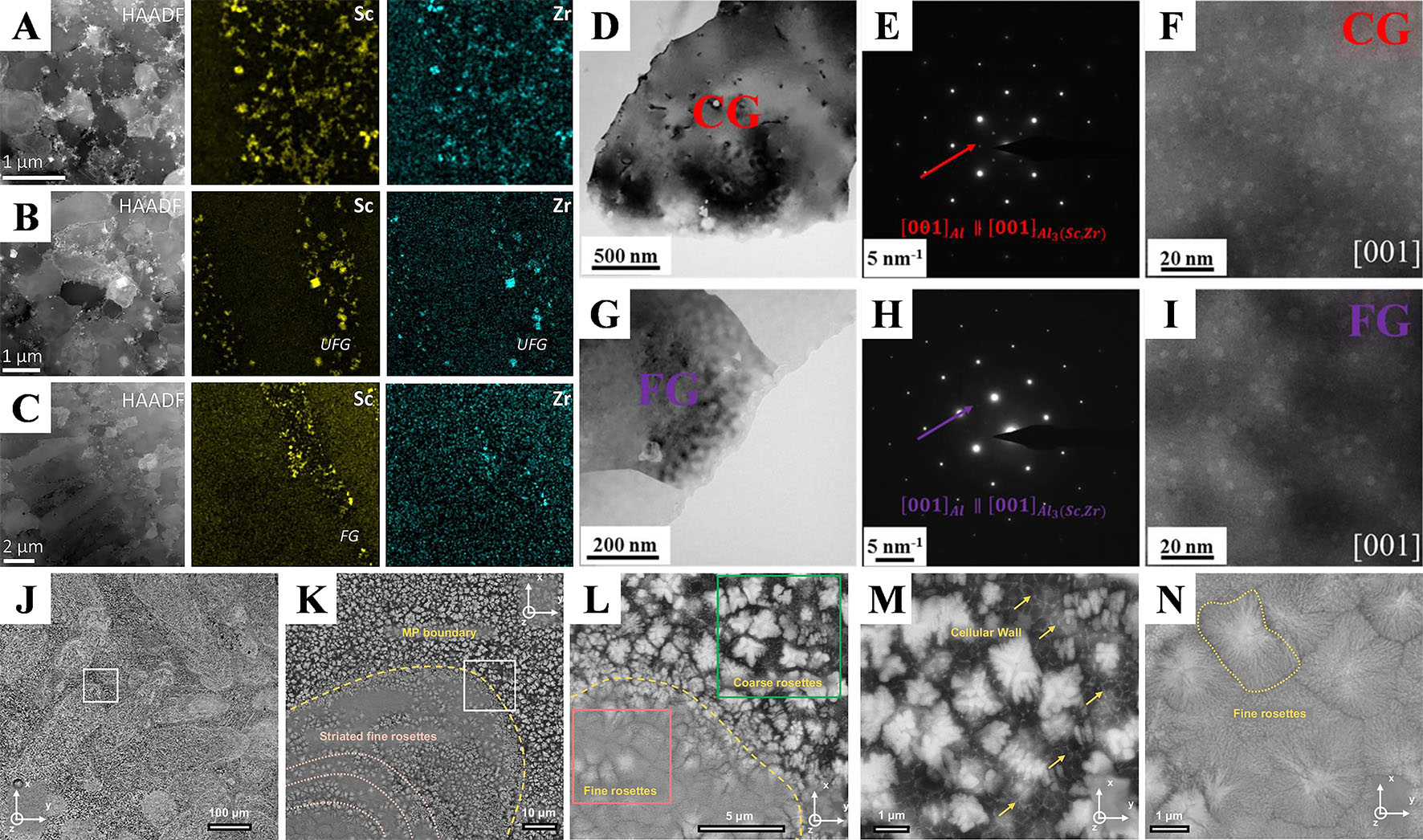

The localized variations in thermal history within the melt pool during L-PBF result in heterogeneously distributed phases in Al alloys. For instance, Li et al. produced an Al-Mg-Mn-Sc-Zr alloy reinforced with nano-scaled planar defects[51]. Their work revealed a significantly higher concentration of Al3(Sc,Zr) phases in UFG regions compared to CCG regions, a consequence of competitive nucleation between the primary Al3(Sc,Zr) phases and the Al matrix, as shown in Figure 3A-C. To enhance the mechanical properties of the bulk samples, heat treatment is generally employed to further regulate the microstructure of Al3(Sc,Zr) precipitates. As depicted in the aged Al-Mg-Sc-Zr alloy, the CG region exhibited a higher density of secondary Al3(Sc,Zr) phases compared with the fine-grained region[71]. Moreover, the average diameter of these secondary precipitates was approximately 1.6 nm, which was markedly smaller than that of the primary precipitates [Figure 3D-I].

Figure 3. Heterogeneous microstructures induced by phase distribution. (A-C) Scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM) and corresponding energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) maps of Sc and Zr elements in different regions of L-PBFed Al-Mg-Mn-Sc-Zr alloy, showing the uneven distribution of the L12-ordered Al3(Sc,Zr) nanoparticles[51]. (D) Bright-field (BF)-TEM image from the CG region of the L-PBFed Al-Mg-Sc-Zr alloy during direct aging; (E) The corresponding selected area electron diffraction (SAED) pattern; (F) High-angle annular dark field (HADDF)-STEM image; (G) BF-TEM image in FG region; (H) The corresponding SAED pattern; (I) HADDF-STEM image[71]. (J) Microstructure on the horizontal view of Al92Ti2Fe2Co2Ni2 alloy produced via L-PBF; (K) Enlarged region outlined in the white box of (J) showing a representative melt pool micrograph; (L) Magnified region outlined in the white box of (K) showing the microstructure across the melt pool boundaries; (M) High-magnification SEM micrograph of the coarse rosettes region taken from the green box of (L); (N) High-magnification SEM micrograph of the fine rosettes region taken from the pink box of (L)[72].

Another representative work is that Shang et al. utilized L-PBF to fabricate an intermetallics-strengthened Al92Ti2Fe2Co2Ni2 alloy, constructing a highly gradient heterogeneous microstructure[72]. This microstructure comprised coarse rosettes with thicker lamellae dominating the melt pool center and fine rosettes with finer lamellar spacing near the melt pool boundaries [Figure 3J-N]. The fine rosette region featured Al3Ti cores surrounded by alternating Al3Ti and Al9(Fe,Co,Ni)2 alternating intermetallic laminate. In contrast, the coarse rosette region was primarily composed of medium entropy Al9(Fe,Co,Ni)2 intermetallics. Attributed to the significant deviation in melting temperature, the Al3Ti initially formed as the cores of the intermetallic rosettes, subsequently facilitating the co-precipitation of Al9(Fe,Co,Ni)2. The complex and periodic thermal cycles, coupled with abundant solutes and a high quenching rate near the melt pool boundaries, promoted the formation of a greater volume fraction of striated fine rosettes. Conversely, coarse rosettes were predominantly observed in the melt pool center.

Similarly, Rakhmonov et al. also demonstrated microstructural variations through L-PBF, fabricating a hypoeutectic Al-7.3Ce-7.7Mg alloy[73]. This alloy exhibited a distinctive grain microstructure, transitioning from cellular-shaped to near-equiaxed eutectic colonies from the bottom to the top of the melt pool. A unique heterogeneity of phase distribution was also observed, with ternary metastable Al13CeMg6 primarily located near the melt pool bottom and stable Al11Ce3 phases concentrated at the melt pool top. These specialized microstructures endow the alloy with high creep resistance.

In response to the demand for excellent mechanical properties at high temperature, novel heat-resistant Al alloys incorporating intermetallic compounds have been reported, often leveraging Al-Si systems known for their printability and workability. Taking the L-PBFed Al-12Si-1.5Ni-2.0Fe alloy as an example, it exhibits superior thermal stability, resulting in the impressive tensile strength of 271 MPa at 300 °C[74]. Fe/Ni segregation, characterized by a strong partitioning effect and low diffusion coefficient, acts as a solid obstacle, inhibiting the coarsening or annihilation of Si cellular structures in the center of the melt pool. Furthermore, the formation of ultra-fine AlFeNi precipitates, heterogeneously distributed at the melt pool boundaries, contributes to the alloy's heat resistance due to their nature as stable intermetallics.

In addition, such a eutectic phase decorated in the cellular structures is also regarded as a typical type of heterogeneity in phase distribution, which plays the pivotal role in printing processability and mechanical performance of additively manufactured Al alloys. On the one hand, the precise design of the eutectic phase can incorporate a low crack susceptibility index, sufficient liquid feeding, and grain refinement to optimize the non-equilibrium solidification path, thus achieving superb printability[75]. On the other hand, the eutectic-decorated cellular structures can effectively inhibit dislocation movement and local damage accumulation during plastic deformation, thereby contributing to exceptional mechanical behavior[76].

MODULATION OF HIERARCHICALLY HETEROGENEOUS MICROSTRUCTURES

Heterostructures play a crucial role in enhancing the mechanical properties of L-PBF fabricated Al alloys. Consequently, extensive research has been conducted to develop strategies for precisely modulating microstructural heterogeneity. In this section, we elaborate on several key factors, including chemical composition, the L-PBF process, and heat treatment.

Chemical composition

As detailed in the preceding section, it can be inferred that the chemical composition exerts the paramount role on the heterogeneous microstructures by controlling solute partition and phase formation during subsequent solidification. Li et al. designed L-PBFed Al-Cu-Mg-Mn-based alloys with different Zr contents[77]. Significant differences were observed in grain morphology and grain size as the Zr content increased. In the alloy without Zr addition, epitaxially grown columnar grains predominated, where prevalent hot cracks mainly propagate along the columnar dendritic boundaries [Figure 4A]. As illustrated in Figure 4B and C, bimodal grains developed in alloys with low to intermediate Zr additions, exhibiting a heterogeneous grain structure. Unexpectedly, high Zr content promoted a fully equiaxed microstructure owing to excessive nucleation particles throughout the melt pool and extended Zr solid solubility

Figure 4. BSE images showing the cross-section microstructure of Al-Cu-Mg-Mn-Zr alloys with different Zr contents of 0 wt.% (A);

Furthermore, the heterogeneous structural characteristics in additively manufactured Al alloys are closely correlated with the addition of various particle reinforcements, including borides, carbides, hydrides, and oxides. Among these, thermally stable in situ TiB2 particles have been widely utilized to modify castable and heat-treatable Al alloys in AM[78,79]. On the one hand, these particles provide effective heterogeneous nucleation sites due to their highly coherent crystallographic orientation relationships with the Al matrix, facilitating columnar-to-equiaxed transition (CET) and thereby refining grains and suppressing crystallographic texture formation[80]. On the other hand, TiB2 particles function as reinforcements, contributing to enhanced strength through mechanisms such as Hall-Petch strengthening, coefficient of thermal expansion (CTE) mismatch strengthening, loading-bearing strengthening, and Orowan strengthening[81,82]. Critically, track overlapping and the subsequent remelting/re-solidification behavior enable uniform dispersion of reinforcements, facilitating fully equiaxed grain formation and mitigating microstructural heterogeneity[83]. By contrast, less stable hydrides and oxides such as ZrH2, TiO2, and YSZ tend to dissolve or react within the Al matrix during laser scanning. This leads to the formation of Al3X particles, which in turn induce the heterogeneous distribution of grain structures, as previously described[56,84,85].

The morphology and distribution of intermetallics have been shown to strongly correlate with the addition of nanoparticles. Sun et al. analyzed the effect of TiC carbides on tailoring the microstructure, crack inhibition, and thermal resistance of L-PBFed AlFeCr[86]. The heterogeneous microstructure in AlFeCr alloy consists of hierarchical intermetallics within the melt pool interior (fibrous Al6Fe eutectic) and along the melt pool boundary (quasicrystalline i-phase and θ-Al13(Fe,Cr)2-4 phase) [Figure 4E]. TiC nanoparticles can not only promote the formation of equiaxed grains through the reduction of required undercooling, but also act as nucleation sites, increasing the volume fraction of intermetallics, as shown in Figure 4F. Additionally, the lower diffusion coefficient of Ti compared to Fe and Cr enhances the thermal resistance of the quasicrystalline icosahedral phase. This specialized heterostructure imparts exceptional mechanical properties and thermal stability to the TiC/AlFeCr alloy, achieving an impressive tensile yield strength of

L-PBF process

During L-PBF, a high-energy moving laser beam is employed to fully melt metal powder in an extremely short time, followed by solidifying the new layer through high cooling rate. The intricate laser-matter interactions and rapid solidification conditions, directly influenced by the L-PBF process, significantly impact the microstructure. In this subsection, we will focus on adjustment strategies that incorporate laser parameters, substrate temperature, and scanning remelting techniques for tailoring heterogeneous microstructures in additively manufactured Al alloys.

Laser parameters

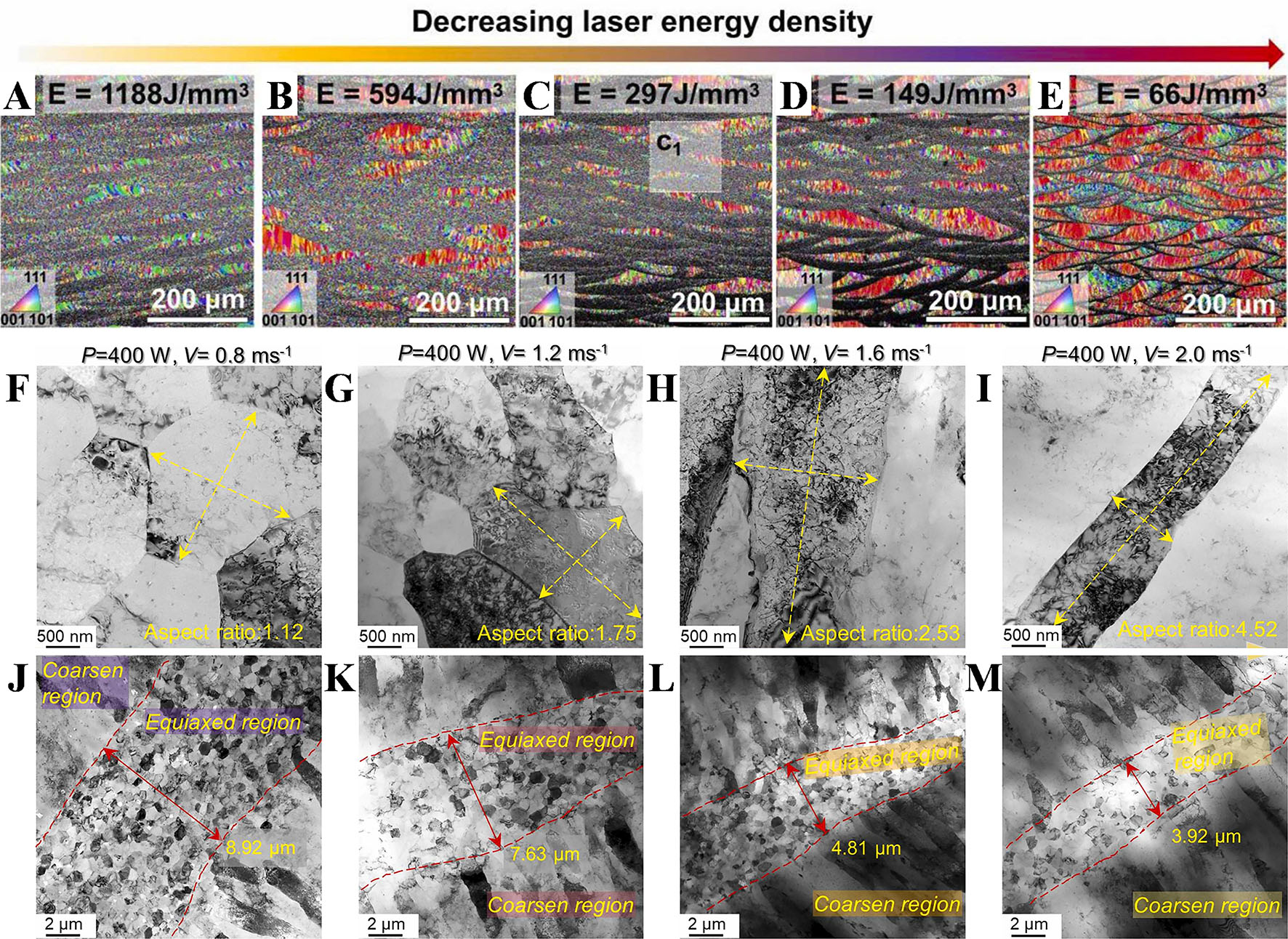

The laser parameters, including laser power, scanning speed, hatching space, laser input mode, and laser spot shape, have been precisely adopted to optimize the solidification conditions at the solid-liquid (S-L) interface. Among these parameters, those associated with input volumetric energy density, particularly laser power and scanning speed, significantly influence the engineering of the heterogeneous microstructures. By manipulating laser energy density, Zhu et al. systematically regulated the microstructure evolution of AL6061MOD alloy fabricated by L-PBF[87]. All alloys present a bimodal grain size distribution consisting of CCGs and UFGs, as depicted in Figure 5A-E. It is apparent that the area fraction of UFGs decreases with reduced input energy density and concurrent faster cooling rate, attributed to the more pronounced solute trapping effects of Sc and Zr. Further, Zhang et al. conducted a comprehensive characterization of the detailed grain structures in both the coarse and fine regions of Al-4.2Mg-0.4Sc-0.2Zr alloys[45]. The results show that increasing the laser scan speed leads to a slenderer coarse grain region at the center of the melt pool and a narrow equiaxed grain region along the melt pool boundary [Figure 5F-M], which correlates with lower G and higher V based on the finite element simulations. However, increasing the laser scanning speed may facilitate high porosity and suppress the grain boundary (GB) segregation of Mg, thereby inducing a transition in fracture mechanism from toughness to brittleness.

Figure 5. Cross-sectional IPF images under different laser energy densities of 1,188 J/mm3 (A); 594 J/mm3 (B); 297 J/mm3 (C);

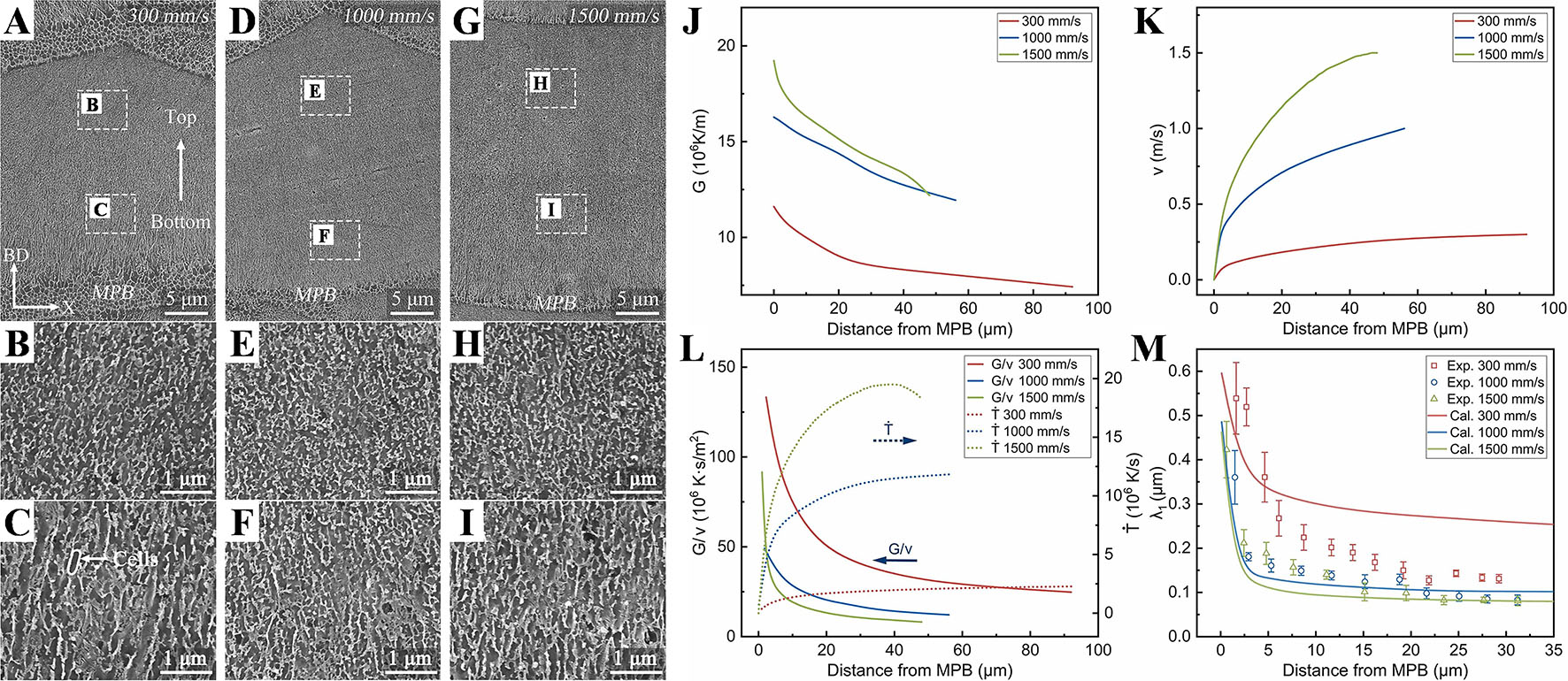

Thanks to the substantial influence of the rapid solidification process, the size and morphology of cellular structures can be well tailored via manipulation of laser parameters. As a typical example, Luo et al. investigated the relationship between laser scanning speed, cellular structure, and mechanical properties[88]. The elevated laser scanning speed not only promotes the growth of the CCG region within the melt pool, but also inhibits the formation of the UFG band near the melt pool boundary [Figure 6A-I]. The results indicate that an increase in scanning speed is related to a reduction in overall cell size, exhibiting a gradient size distribution along the BD. Such variation in cell size is closely correlated with the G and V across the melt pool, as illustrated in Figure 6J-M. These finer cells, specifically the continuous networks of the Al9Ni2 phase, remarkably impede dislocation motion, thereby contributing significantly to the superior strength.

Figure 6. SEM images of pronounced cellular structures form the bottom to the top of melt pool at laser scanning speed of 300 mm/s (A); 1,000 mm/s (D); 1,500 mm/s (G) in the near eutectic Al-Ni-Sc-Zr alloy fabricated by L-PBF; Magnified images of cellular structures at different positions of the melt pool at scanning speed of 300 mm/s (B and C); 1,000 mm/s (E and F); 1,500 mm/s (H and I); Variation of G (J) and V (K) at the S-L interface; (L) Curves of G/V and cooling rate

Another example is that Pérez-prado et al. prepared an AlFeCr alloy with the heterogeneous distribution of second phases using L-PBF, reaching remarkable thermal stability with a yield strength of up to 273 MPa at 300 °C[68]. Ubiquitous fine i-phase particles are ubiquitously dispersed within the melt pool interior, while slightly coarser particles are located along the boundaries, which is consistent with the local thermal gradients within the melt pool. It is evident that decreasing energy density, coupled with progressively higher solidification rate, refines the diameters of intermetallic particles.

As is widely acknowledged, the variance in hatching space (the separation between adjacent laser scan paths) can also lead to differences in input energy density. Large hatch spacing generates insufficient track overlapping and poor fusion, whereas small hatch spacing induces high porosity due to melt pool instability. Consequently, an appropriate hatch spacing, as a key factor, is essential for modulating microstructural heterogeneity. For instance, Ekubaru et al. achieved a strength-ductility balance in Sc/Zr-modified Al-Mg alloys manufactured through L-PBF by carefully tuning the degrees of hatch spacing[89]. The optimal hatch spacing with sufficient track overlap gives rise to a large number of track-track melt pool boundaries, which typically increases the volume fraction of Al3(Sc,Zr) precipitates and subsequently enhances the formation of UFGs. Both GB and precipitate strengthening mechanisms substantially contribute to the mechanical properties. These findings underscore the critical role of track overlapping in controlling grain structure.

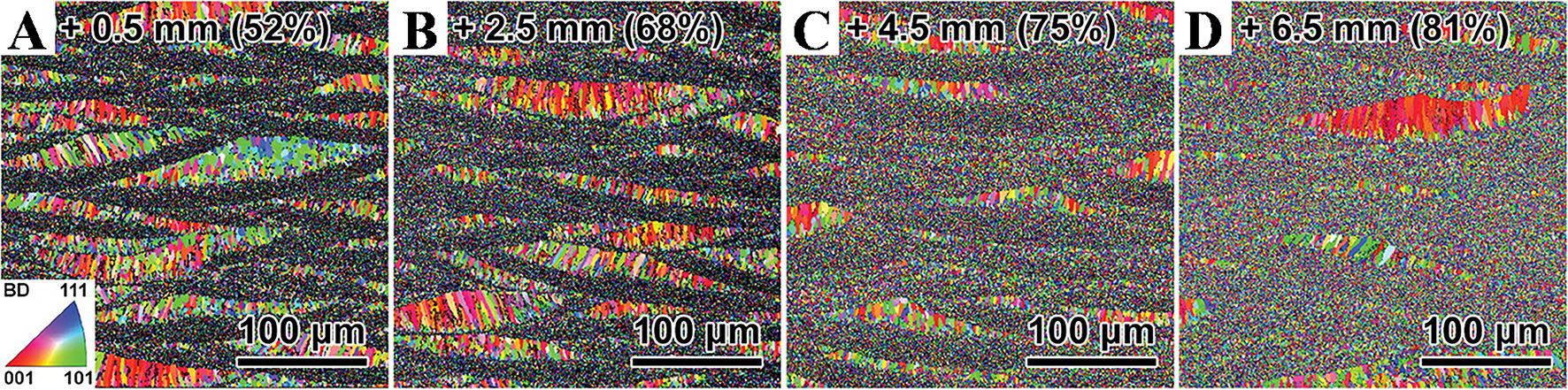

Moreover, in the case of laser parameters, while the laser defocusing distance does not affect laser volumetric energy density, it can alter the distribution of laser density by adjusting the relative position of the building plane with respect to the focal point. As the positive defocusing distance increases, the laser beam diverges, leading to a more uniform energy intensity distribution. This effect reduces both the cooling rate and thermal gradient. A typical example is the L-PBF fabricated Sc/Zr-modified Al6061 with heterogeneous microstructure, as reported by Hu et al.[46]. The fraction of UFGs increases from 52% to 81% along with the defocusing distances, as illustrated in Figure 7, which is attributed to the increasing fraction of heterogeneous nucleation sites. It is worth emphasizing that equiaxed grains with higher GB density are conducive to mitigating thermal stress and retarding tortuous crack propagation. However, the plastic instability manifested by the formation of Lüders bands, which arises from the interaction between the heterogeneous microstructure and mobile dislocations, is detrimental to achieving a strength-ductility synergy.

Figure 7. IPF maps of the Sc/Zr-modified Al6061 through L-PBF by various laser defocusing distances of +0.5 mm (A), +2.5 mm (B),

Substrate temperature

The substrate temperature represents another remarkable processing parameter that modifies the microstructure by regulating the cooling rate and thermal gradient during L-PBF. Santos Macías et al. investigated the effect of build platform temperature on the microstructural features and mechanical performance in AlSi10Mg alloy prepared via L-PBF[62]. As shown in Figure 8A-F, the variations in distinguishable zones of cellular structure with the substrate temperature increase from 35 to 200 °C can be categorized as follows: (1) Si-rich precipitates coarsen; (2) some rounded Si-rich precipitates transform into needle shapes; (3) the regions of CMP and HAZ expand. Further characterization using focused ion beam (FIB)/SEM confirms the increased thickness and reduced connectivity of the tubular cellular microstructure processed at a 200 °C build platform temperature [Figure 8G-L]. Meanwhile, it is found that the grain size and morphology are relatively unaffected by substrate temperature. Due to the low interconnectivity and thicker Si-rich eutectic network, preheating the substrate negatively impacts damage initiation and plastic deformation. Additionally, Sun et al. prepared an Al-Mn-Mg-Sc-Zr alloy utilizing L-PBF at elevated substrate temperature[90]. It is demonstrated that high build platform temperature enhances both mechanical properties and fatigue performance in a low-cycle fatigue regime. The increase in substrate temperature reduces the thermal gradient within the melt pool, which generates a higher volume fraction of equiaxed grains. Therefore, controlling the heterogeneous microstructure can be achieved by manipulating the substrate temperature.

Figure 8. SEM micrographs of the FMP zone of L-PBFed AlSi10Mg with substrate temperature of 35 °C (A) and 200 °C (B); of the CMP zone with substrate temperature of 35 °C (C) and 200 °C (D); of the HAZ zone with substrate temperature of 35 °C (E) and 200 °C (F); Focused ion beam (FIB)/SEM tomographies of Si-rich eutectic network of FMP (G); CMP (H) and HAZ (I) zones with substrate temperature of 35 °C; of Si-rich phases of FMP (J); CMP (K) and HAZ (L) zones with substrate temperature of 200 °C[62].

Scanning remelting

Laser surface melting is an innovative technology of surface treatment that involves re-scanning the component surface with a high-energy laser beam to improve surface quality and eliminate defects. Notably, researchers have applied a similar approach in AM through layer-by-layer remelting to refine the microstructure and mechanical properties.

Taking the AlMgSiScZr alloy as an example, in the double melt mode, each printed layer is subjected to two consecutive laser scans[91]. During the first scan, a bimodal grain structure forms, characterized by equiaxed grains near the melt pool boundary and CCGs in the center of the molten pool. This structure arises due to the heterogeneous nucleation behavior of precipitating agents. Influenced by the thermal effect of the preceding laser scan, the temperature distribution during the second scan becomes more uniform and prolongs the solidification time, promoting the generation of dense Al3(Sc,Zr) particles to refine the grain size. Furthermore, Zhou et al. demonstrated that scanning remelting pronouncedly mitigates the internal defects and ameliorates microhardness for the AlSi10Mg alloy[92]. However, the current remelting strategy with identical process parameters has limited effects on improving physical properties. Moreover, the remelting process inevitably declines production efficiency and incurs additional costs.

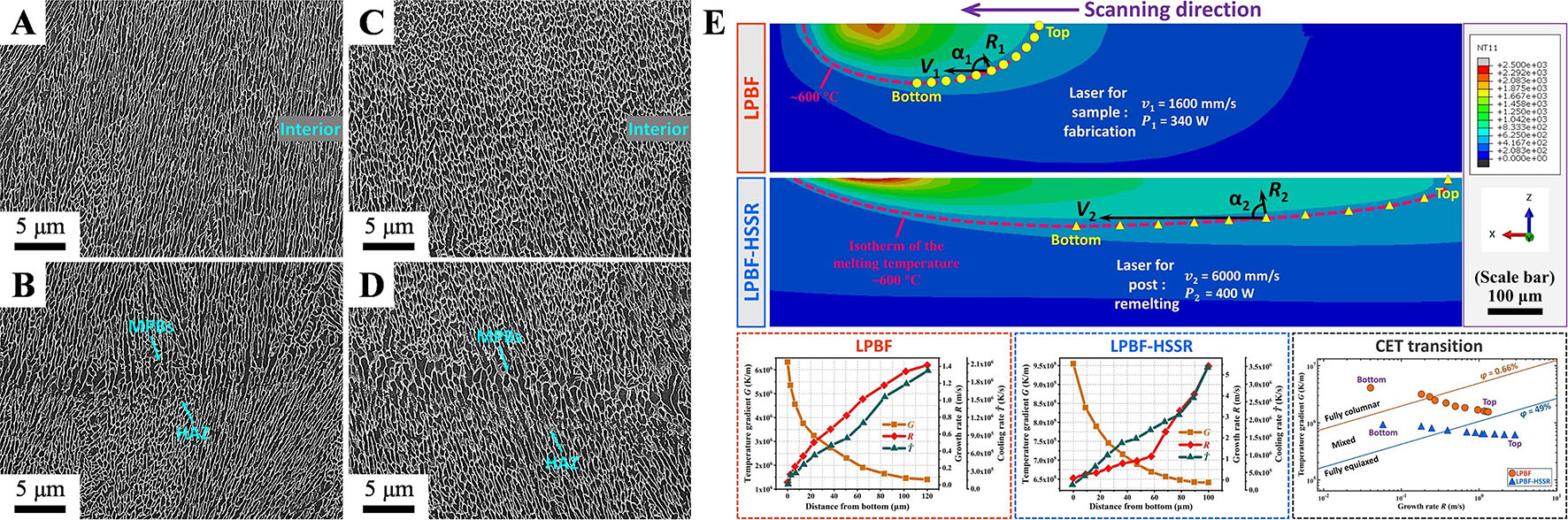

To address this dilemma, Shi et al. proposed a novel and practical high-speed scanning remelting (HSSR) technique for L-PBFed AlSi10Mg[93], achieving an exceptional tensile strength of 496 MPa and a fracture elongation of 21.4%. Detailed characterization and finite element method (FEM) model were conducted to uncover the microstructure adjustment through HSSR [Figure 9]. The remelting strategy with high power and high scanning speed not only refines grains and cellular structures by altering the solidification conditions, but also promotes the CET model. Additionally, abundant fine nanoparticles precipitated from the supersaturated Si element in the Al matrix under the significant thermal cycling effect. The refined microstructure, high-density boundary, and large amounts of nanoparticles remarkably enhance dislocation accumulation, thereby greatly promoting the strain hardening and mechanical performance. Importantly, the increased irregularity of the molten pool and incoherent deformation between adjacent grains collectively suppress crack initiation and propagation, thus enhancing the impact toughness of the AlSi10Mg alloy[94].

Figure 9. SEM images of cellular sub-structure of AlSi10Mg produced by L-PBF (A and B) and by high-speed scanning remelting (HSSR) (C and D); (E) Molten pool temperature field and solidification conditions[93].

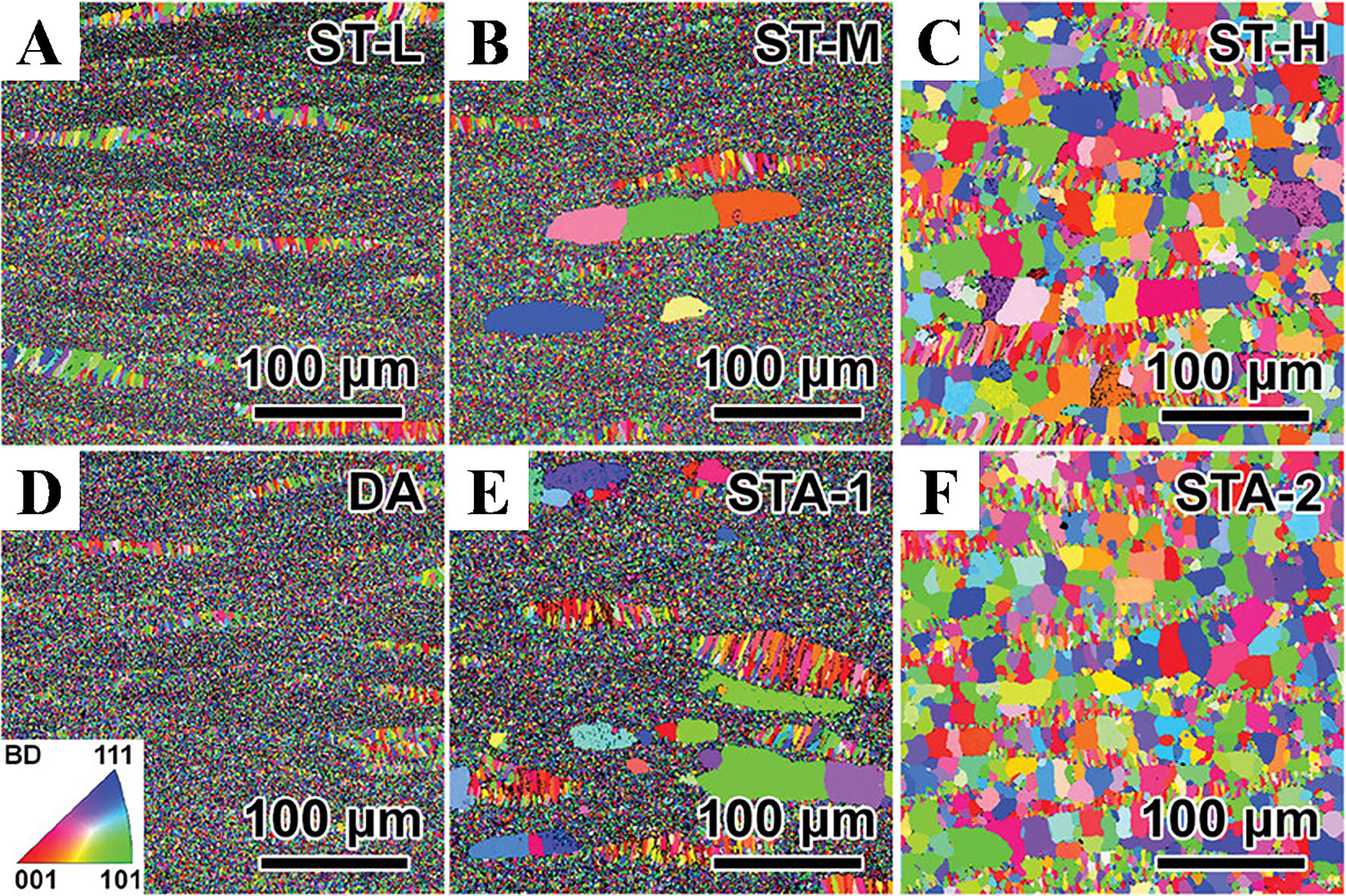

Heat treatment

For as-built samples, the extremely fast cooling rate during L-PBF generates a high density of dislocations, residual stress, and high-energy GBs, which readily facilitate grain recrystallization in the subsequent heat treatment. This effect is particularly pronounced in the fine-grained Al alloys. Consequently, the optimization of heat treatment plays a paramount role in modulating the heterogeneity of grain structure. For instance, Hu et al. conducted a comprehensive investigation on the microstructural evolution of Sc/Zr-modified Al6061 under six typical heat treatment conditions, including solution treatment + natural aging (ST), direct aging (DA) and solution treatment + artificial aging (STA) at different temperatures[46]. Their findings revealed that the grain growth is negligible at relatively low temperatures [Figure 10], preserving the alternating distribution of CCGs and UFGs. Moreover, with the increasing temperature, the changes in grain size become more obvious, revealing a strong correlation between grain coarsening behavior and heat treatment. Thanks to the grain growth, the weakening and elimination of the Lüders band is achieved, accompanied by the enhancement in strength, plasticity, and thermal conductivity. Similar phenomena regarding the significant dependence of heterogeneous grain structure on heat treatment have also been observed in additively manufactured Al-Zn-Mg-Cu-Nb alloys[49].

Figure 10. IPF maps of the L-PBF fabricated Sc/Zr-modified Al6061 with the defocusing distance of +4.5 mm under different heat treatments: ST-L (A), ST-M (B), ST-H (C), DA (D), STA-1 (E), and STA-2 (F)[46].

Additionally, for near-eutectic Al alloys with heterogeneous cellular structure, such as Al-Si, Al-Ni, and Al-Fe, denoted as non-heat treatable, researchers typically investigate their thermal stability and microstructural evolution during prolonged thermal exposure[95]. For example, in the Al-Ni-Sc-Zr alloy aged isothermally at 250 °C for 100 h, most of the distinct Al9Ni2 cellular structures, which are divided into the intact-coarse, intact-fine, and partial cell regions, remain clearly observable[67]. Following thermal exposure to 300 h, the majority of Al9Ni2 eutectic phase transforms into nanoscale particles, while a few residual intact-fine Al9Ni2 cells maintain their original morphology. It is also worth mentioning that coarse particles are observed at the columnar grains, where these boundaries can facilitate atom diffusion and accelerate precipitate coarsening. After prolonged thermal exposure of up to 500 h, the particles in the intact-fine and partial cell regions exhibit minimal coarsening, thus contributing to excellent thermal stability.

MECHANICAL PROPERTIES

In the previous section, we discussed various methods for modulating the heterogeneous structures in additive-manufactured Al alloys. Here, we focus on the underlying mechanisms of the effect of remarkably heterogeneous structures on mechanical properties, including tensile, fatigue, and creep behaviors.

Quasi-static mechanical properties

As the lightweight material is extensively utilized across various fields, the tensile properties of Al alloys are the primary factor for structural applications. Tensile properties of typical alloys prepared by L-PBF are listed in Table 1.

Summary of the tensile properties for L-PBF of typical Al alloys with heterogeneous structures. DA, ST, STA, and As-SR represent direct aging treatment, solution treatment, solution + artificial aging treatment, and as-stress-relieved, respectively

| Family | Alloy | Condition | Yield strength (MPa) | Ultimate tensile strength (MPa) | Elongation to fracture (%) | Ref. |

| Heterogeneity in grain structure | Al-Cu-Mg-Zr | As-built | 446 | 451 | 2.7 | [96] |

| Al-Cu-Li-Sc-Zr | As-built | 482 | 539 | 8.8 | [97] | |

| DA | 520 | 553 | 2.9 | |||

| ST | 371 | 447 | 4.1 | |||

| Al-Mn-Mg-Sc-Zr | As-built | 438 | 452 | 20.0 | [98] | |

| DA | 571 | 573 | 16.0 | [99] | ||

| Al-Zn-Mg-Cu-Nb | As-built | 332 | 422 | 17.1 | [100] | |

| STA | 412 | 505 | 12.4 | |||

| Al-Zn-Mg-Sc-Zr | As-built | 284 | 386 | 18.4 | [101] | |

| STA | 418 | 436 | 11.1 | |||

| Al-Ni-Ti-Zr | As-built | 266 | 331 | 17.0 | [102] | |

| DA | 335 | 345 | 10.0 | |||

| Heterogeneity in cellular structure | Al-Si-Mg (AlSi10Mg) | As-built | 305 | 465 | 6.5 | [103] |

| ST | 98 | 185 | 16.7 | |||

| STA | 194 | 254 | 7.0 | |||

| Al-Si-Fe-Mn-Ni | As-built | 373 | 602 | 4.2 | [104] | |

| Al-Ni-Sc-Zr | As-built | 350 | 456 | 5.9 | [105] | |

| DA | 470 | 530 | 11.3 | |||

| Al-Ce-Mg | As-built | 300 | 438 | 9.3 | [106] | |

| 303 | 442 | 6.2 | ||||

| Heterogeneity in phase distribution | Al-Ce-Ni-Mn | As-SR | 258 | 370 | 10.0 | [107] |

| Al-Ce-Ni-Ti-Zr | As-SR | 427 | 573 | 4.7 | [108] | |

| Al-Fe-V-Si-Sc | DA | 649 | 865 | 2.1 | [109] | |

| Al-Fe-Cu-Zr | As-built | 500 | 528 | 2.0 | [110] |

The enhancement in strength is primarily attributed to fine-grained strengthening, solid solution strengthening, precipitation strengthening, and dislocation strengthening[111,112]. Despite taking full advantage of these strengthening contributions, it remains essential to develop additional strengthening mechanisms for achieving L-PBFed Al alloys with an optimized combination of ultrahigh strength and ductility.

To evaluate the mechanical properties in heterogeneous structures, researchers typically utilize hardness testing or nanoindentation experiments to measure hardness and Young's modulus, complemented by SEM for characterizing indentation morphologies[113,114]. For instance, Delahaye et al. employed nanoindentation to assess the hardness of typical cellular structures in AlSi10Mg alloy[63]. The results revealed distinct variations in hardness distribution characteristic of the FMP, CMP, and HAZ. Specifically, the HAZ was identified as a weak zone due to the presence of coarse Si particles and partial breakdown of the cellular network. Similarly, fluctuations in microhardness have been observed in additively manufactured Al alloys with inhomogeneous grain size distributions[49,71,115]. Fine-grained regions are considered hard domains, while coarse-grained regions are regarded as soft domains, attributed to differences in grain size and the dispersion of secondary phases. Additionally, variations in measured hardness throughout the molten pool are also reported in L-PBF-processed Al-Ce, Al-Fe series alloys with heterogeneity in phase distribution[72,86,116]. Therefore, the HDI stress arises in L-PBFed Al alloys with heterogeneous structures, promoting extra kinematic hardening during plastic deformation.

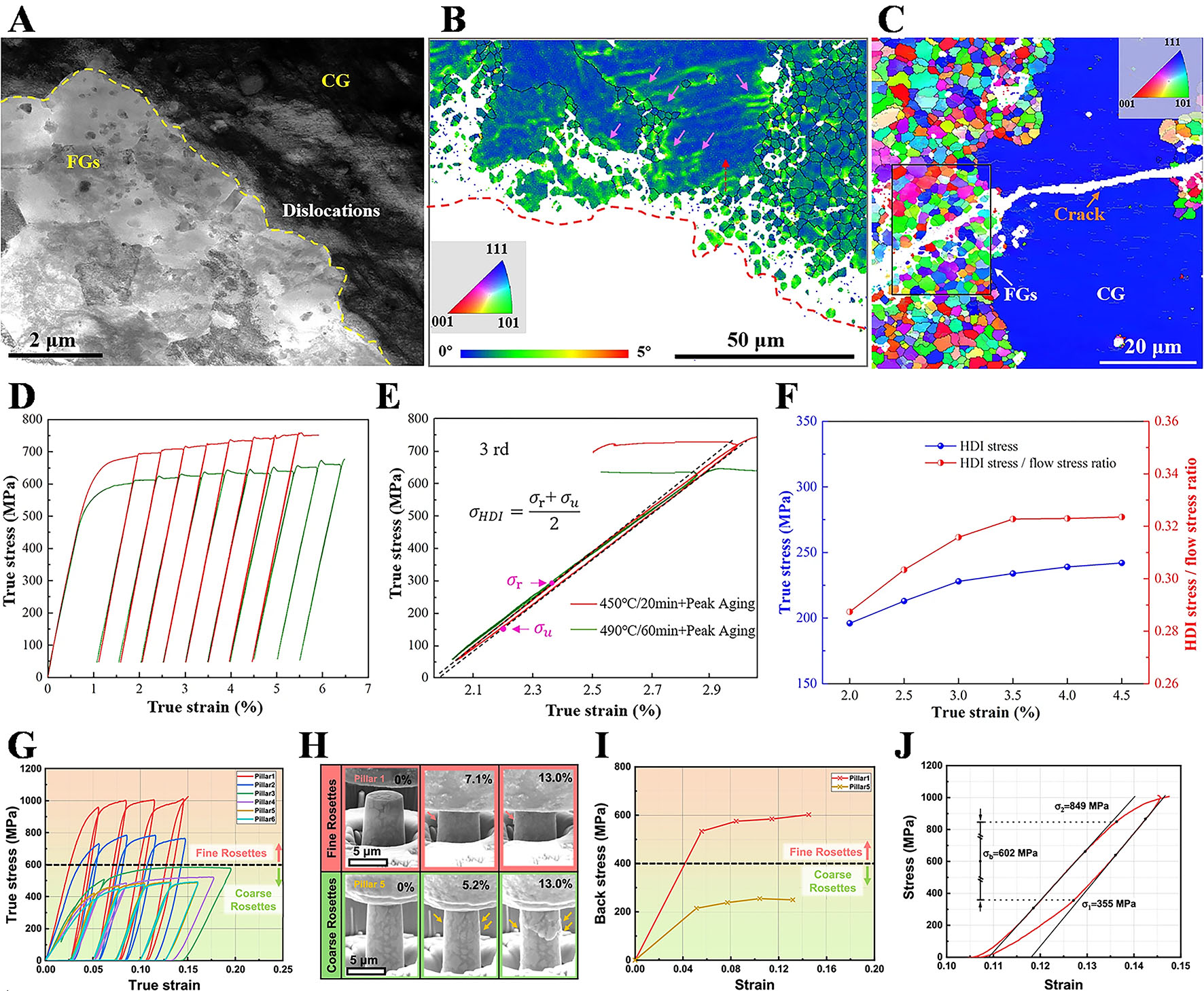

The loading-unloading-reloading (LUR) tensile test serves as a common method to quantify the HDI stress generated by GNDs at the interfaces between hard domains and soft domains. The specific values of HDI stress (σHDI) and effective stress (σeff) can be calculated from the following equations[113,117]:

where σu and σr are the unloading and reloading yield stress, respectively. σflow represents the global flow stress of the sample. Thus, the results of HDI stress measurement through LUR curves at different strain levels are feasible.

The stress-strain curves of additively manufactured Al alloys with heterogeneous grain structure exhibit a distinct deformation plateau and Lüders bands, as well as negligible work hardening and acceptable elongation. These characteristics are primarily associated with the coordinated deformation ability and dislocation storage capability. Owing to the deformation inhomogeneity near interfaces of coarse and fine grain zones, a higher density and remarkable accumulation of dislocations are detected in the coarse grain zone of Al-Zn-Mg-Cu-Nd alloy after failure[49], as shown in Figure 11A. In contrast, the reduced dislocation's mean free path and enhanced dislocation annihilation at GBs restrict dislocation accumulation in the fine grain zone. Another notable feature is that the value of kernel average misorientation (KAM) across the interface is higher than that within the coarse grain zone, implying the prominent GND pileups [Figure 11B]. Moreover, intergranular fracture in the fine grain zone and transgranular fracture in the coarse grain zone are the fracture behaviors of L-PBFed Al-Zn-Mg-Cu-Nb alloy, where the intrinsic properties of ductile coarse grains can restrict and blunt crack propagation, thereby enhancing the ductility [Figure 11C]. To probe the interaction of forward stress and back stress, the distinct hysteresis loops and increase in HDI stress reflect effective work hardening ability based on the results of the LUR curves

Figure 11. (A) TEM map showing the dislocations in the heat-treated Al-Zn-Mg-Cu-Nb alloy prepared by L-PBF after tensile testing; (B) KAM image of the tensile fracture surface of the sample; (C) Crack propagation path during three-point bending experiment; (D) The LUR curves under different heat treatment; (E) The third hysteresis loop from (D), utilized for calculating HDI stress and effective stress; (F) The statistics of HDI stress and the ratio of HDI stress to flow stress[49]. (G) The curves of true stress-strain obtained from in situ micropillar compression tests conducted on both fine and coarse rosette regions of the L-PBFed Al92Ti2Fe2Co2Ni2 alloy; (H) SEM micrographs of pillars under in situ compression; (I) Back stress measurements for micropillars; (J) A complete hysteresis loop for a pillar in fine rosette region at 14% strain[72].

Additionally, recent findings by Shang et al. have suggested that the appropriate incorporation of nanoscale medium entropy intermetallics with heterogeneous distribution can significantly enhance ultra-high engineering stress[72,118]. Micropillar compression tests were employed to investigate the underlying mechanisms of the pronounced strain hardening in the as-printed Al92Ti2Fe2Co2Ni2 alloy. The significant hysteresis loops and back stress in both the fine rosette region and coarse rosette region imply the reliable HDI stress adjacent to the Al-intermetallic interface [Figure 11G-J]. It is noteworthy that the flow stresses in the fine rosette region occasionally reached 1 GPa. Furthermore, abundant stacking faults and complex dislocations suggest plastic deformation within the intermetallics, thus generating back stress at the interfaces between Al9(Fe,Co,Ni)2 and D022-Al3Ti in the fine rosette region. In macroscale compression tests, the heterostructured alloy printed at a 200 W laser exhibits high strength (over 700 MPa) and notable plastic deformability (approximately 20%).

In situ synchrotron X-ray diffraction enables a clearer understanding of the precipitate-matrix interaction and the evolution of dislocation configurations during the deformation. In the elastic deformation stage of additively manufactured Al-Mg-Sc-Zr alloys, both the matrix and the particles exhibit similar lattice strains and undergo uniform deformation[119]. Upon yielding, intensified lattice strain mismatch between the matrix and precipitates triggers severe dislocation pileups and increases dislocation density. In the plastic regime, the icosahedral quasicrystalline structure accommodates elastic strain, causing the quasi-linear behavior of Al85Mn15 precipitates formed during heat treatment. This promotes dislocation accumulation in the matrix. Meanwhile, nanoscale secondary Al3(Sc,Zr) phases impede the cross-slip of screw dislocations through a shearing mechanism, forming tangled dislocation networks within grains. Moreover, the precipitation of solute atoms diminishes the solute drag effect on edge dislocations, thereby enhancing their annihilation potential.

The evolution behaviors of heterogeneous microstructures under straining in AlSi10Mg alloy have been systematically investigated. Due to the notable discrepancies in mechanical responses, a high density of GNDs is introduced near the Al/Si interfaces, effectively accommodating the strain incompatibility between the hard Si-rich network and the soft Al matrix. Li et al. implied the constraint imposed by the continuous cellular structure on the matrix through post-mortem TEM images and transmission Kikuchi diffraction (TKD) results[103]. The high density of GNDs and large local misorientations at Al/Si interfaces impart the outstanding work hardening capacity and flow strength. Meanwhile, high strain gradients and substantial GNDs are observed at the interfaces of FMP, CMP, and HAZ, attributed to variations in Si phases[120,121]. The continuity of the cellular structure profoundly influences strain partitioning under deformation. A high value of KAM reveals severe deformation at the melt pool border, compared with the interior of the molten pool[122]. Spheroidized Si creates weak regions that promote strain localization and void nucleation, thereby facilitating crack propagation within the HAZ and ultimately leading to failure.

Moreover, to uncover the effect of heterostructured melt pool on mechanical behavior, modeling and numerical simulation serve as effective approaches across multiple scales. Li et al. proposed the representative volume elements and a homogenized constitutive model for the CMP, FMP, HAZ, and bulk microstructure[123]. This multiscale microstructure-based framework evaluates the flow behavior of heterogeneous cellular structures with high precision, further corroborating the inhomogeneity of plastic deformation.

Under thermal cycling loads in practical applications, the behavior of heterogeneous microstructures is directly related to their properties. Heterogeneous grain structures, which are characterized by variations in grain size across different regions, can significantly influence a material's response to thermal cycling. Finer-grained regions generally offer higher resistance to deformation through the mechanism of grain boundary strengthening. However, during thermal cycling, these regions are more prone to stress concentration at grain boundaries, primarily due to the mismatch in thermal expansion coefficients between individual grains and the surrounding matrix[124]. This thermal expansion mismatch can lead to localized plastic deformation, microcrack formation, and ultimately failure initiation at these boundaries. In contrast, coarser-grained regions, although potentially less effective in terms of strength enhancement, may exhibit superior resistance to crack propagation under cyclic thermal loading due to their larger grain size and more stable microstructural configuration. The overall thermal cycling behavior of heterogeneous materials depends on the balance between the strength of fine grains and the crack resistance of coarse grains.

Cellular structures that are often formed during rapid solidification processes or through specific heat treatments can exhibit complex thermomechanical behavior under thermal cycling. The cell walls, typically composed of harder phases, provide structural support to the surrounding matrix. However, during thermal cycling, these cell walls may undergo deformation due to differential thermal expansion between the cells and the matrix. Notably, larger cells are more prone to stress concentration and subsequent deformation, which can lead to crack initiation and propagation. In contrast, a finer cell structure can enhance thermal stability by offering more pathways for stress dissipation, thereby minimizing the potential of crack formation. The overall performance of cellular structures under thermal cycling is significantly influenced by the size, distribution, and mechanical strength of the cell walls.

The heterogeneous phase distribution significantly influences material behavior due to varying thermal expansion among phases. Hard phases provide strengthening but have lower thermal expansion coefficients than the matrix, which can cause stress concentration at phase boundaries[125]. During thermal cycling, this mismatch may lead to localized stress, resulting in delamination or crack initiation. In contrast, a uniform dispersion of strengthening phases improves thermal stability by reducing stress accumulation[126]. Therefore, optimizing heterogeneous materials requires precise control over phase size, distribution, and interfacial properties to minimize thermal cycling effects.

Fatigue property

Fatigue refers to the process of crack initiation or complete fracture in materials subjected to cyclic loading, which accounts for the failure of most engineering components. For the assurance of structural integrity and operational safety, fatigue performance is regarded as a key evaluation criterion, particularly in the application of metal AM in the aerospace industry. In comparison to the conventional casting processes, the L-PBFed Al-12Si demonstrates excellent strength and toughness, but relatively lower fatigue strength[127]. Despite these alloys exhibiting excellent printability, their reduced fatigue resistance typically stems from a variety of factors, including intrinsic defects (such as keyhole, lack of fusion and gas pore defects)[128], residual stress[129], and surface roughness[130], which are inevitable in the non-equilibrium solidification of L-PBF[131]. Among these, residual stress and surface roughness can be effectively eliminated through stress-relief annealing, substrate preheating, and surface machining[132-134]. However, even if a void-free condition can be achieved via hot isostatic pressing (HIP) or other feasible solutions, microstructural coarsening and the associated degradation of mechanical properties still remarkably impair fatigue resistance[135,136]. Thus, the influence of intrinsic defects and microstructures on fatigue performance has become an expanding area of research in near-eutectic Al-Si-based alloys prepared by L-PBF.

The investigations by Zhang et al. have revealed the fracture behavior of L-PBFed AlSi10Mg alloys[137]. The fracture surface can be clearly divided into three distinct characteristic regions: the crack initiation source (CIS), the crack propagation zone (CPZ), and the overload fracture zone (OFZ). The CIS originates from imperfections on the surface or subsurface with higher stress concentration, serving as the nucleation and initiation sites for fatigue cracks.

The representative study by Wu et al. highlights the impact of defect population on the anisotropic fatigue performance of AlSi10Mg produced via L-PBF[138]. Profuse defects varying in sizes and shapes were detected through X-ray computed tomography in all specimens, including over 90% identified as gas porosity defects with an equivalent diameter below 80 μm, and less than 1% pancake-shaped lack of fusion defects with an equivalent diameter exceeding 160 μm. According to an equivalent ellipsoid model applied to large oblate defects, anisotropy in defect orientation angle was observed. Such larger effective defect sizes within the vertical build plan result in higher fatigue strength in the horizontal direction.

To gain further insight into the evolution of fatigue damage arising from the interplay between melt pool structures and manufacturing defects, Wu et al. further investigated the mechanical behavior of additively manufactured AlSi10Mg alloys under high cycle fatigue (HCF) and low cycle fatigue (LCF) using in situ synchrotron X-ray tomography and diffraction[139]. A new transition from defect-dominated short fatigue crack initiation under HCF to meso-structure sensitive fatigue crack propagation under LCF was identified. More specifically, under the HCF condition, the fatigue cracks initiate at surface defects, with minimal influence of the melt pool boundaries on the crack propagation direction. Conversely, under the LCF condition, strain localization and micro-void nucleation at the melt pool boundaries cause crack propagation predominantly along these boundaries. Analyses of fracture surfaces, 3D reconstructions of micro-void distributions, and measurements of strain localization in terms of GNDs from post-mortem test samples collectively provide novel insights into the intrinsic relationship between fatigue behavior and intricate heterostructured architectures.

Furthermore, characterizing fatigue crack propagation pathways using C(T) samples provides critical insights into failure mechanisms and their correlation with microstructural features[140]. The near-threshold regime, the Paris crack growth regime, and the fast crack growth regime in fatigue crack growth (FCG) characteristics of as-built L-PBF-processed AlSi10Mg were systematically investigated by Paul et al., emphasizing the impact of micro and mesostructured features on fatigue behavior[141]. The near-threshold region is predominantly governed by Si-enriched eutectic cellular structures filled with GNDs, which act as effective barriers to inhibit short-crack propagation. In the Paris regime, the interaction volume of the stress field and the plastic zone at the crack tip transitions from a cell structure within the melt pool to the mesostructural melt pool boundaries. This results in a more tortuous crack path, thereby reducing the crack propagation rate. The rough and tortuous crack paths observed in the fast crack growth region of the fracture surface demonstrate that crack deflection predominantly occurs along the melt pool boundaries. This phenomenon is primarily attributed to strength degradation at the melt pool boundaries, which reduces the stress intensity at the crack front and consequently leads to crack-tip blunting[142].

On the basis of high density, the elevated strength of alloys directly contributes to sufficient fatigue strength. Meanwhile, the deformation interactions within heterogeneous microstructure exert a conspicuous effect on improving fatigue performance. Sun et al. explored the impact of microstructural transition on the fatigue properties of Al-Mn-Mg-Sc-Zr alloy[90]. They demonstrated that both the GBs of equiaxed grains and the alternating strain distribution between coarse and fine grains act as effective barriers to fatigue crack propagation, thereby delaying localized strain damage and achieving satisfactory fatigue resistance[143]. In addition, the inhomogeneous distribution of Al3(Sc,Zr) phases causes disparities in resistance under long-term cyclic loading[115]. During the L-PBF process, the primary Al3(Sc,Zr) phase with nanoscale dimensions preferentially precipitated in equiaxed grains, while the secondary Al3(Sc,Zr) phase with a size less than

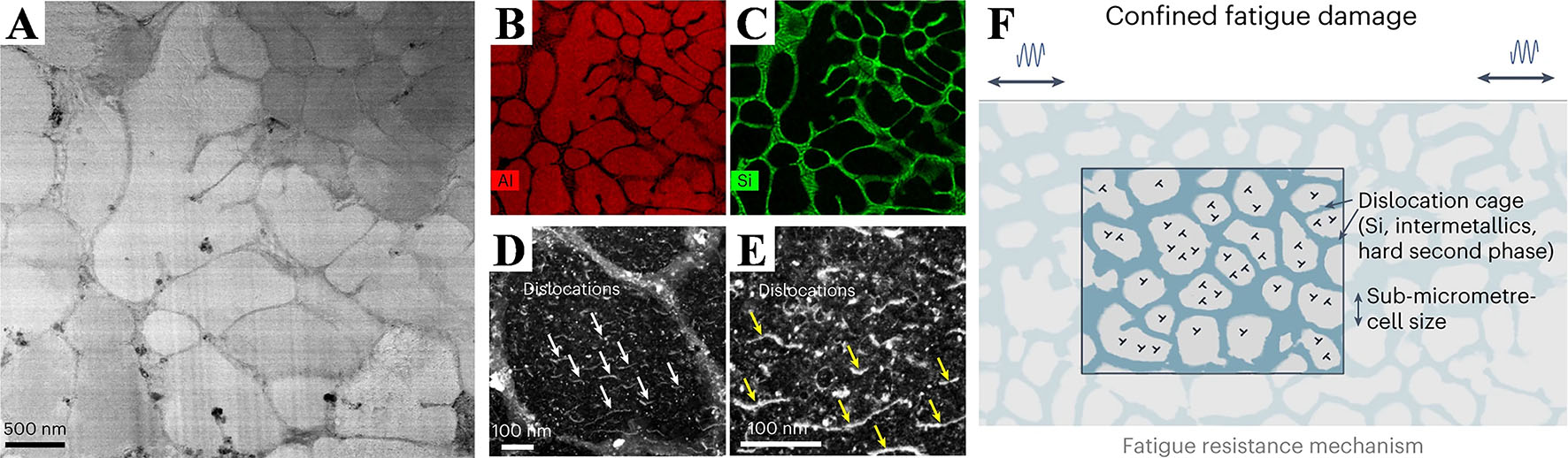

In another study, Dan et al. reported an ultrahigh fatigue resistance phenomenon in nano-TiB2-decorated AlSi10Mg (NTD-Al) fabricated by L-PBF[144]. As shown in Figure 12, the continuous three-dimensional (3D) dual-phase cellular nanostructure (3D-DPCN) acts as a strong volumetric 3D dislocation barrier nanocage to trap dislocation motion and inhibit localized fatigue damage accumulation during fatigue loading. Based on the in situ microfatigue test, the unique microstructure enables the intrinsic fatigue strength of the NTD-Al alloy to approach tensile strength, achieving the highest fatigue strength of all the Al alloys.

Figure 12. (A) TEM characterization of the intact Si cellular structure on the nano-TiB2-decorated AlSi10Mg after 107 fatigue cycles at a maximum stress of 260 MPa (R = 0.1); EDS maps for local element distribution of Al (B) and Si (C); (D and E) Individual dislocations inside the Si nanocellular structure; (F) Schematic showing the fatigue resistance mechanism[144].

Creep property

Creep performance is critical for the reliable operation of metallic components subjected to prolonged stress at elevated temperatures. Due to the relatively low melting temperature of Al alloys, studies on their creep behavior are mainly conducted within the temperature range of 200-300 °C. Glerum et al. revealed the creep response and microstructural evolution of eutectic AlSi10Mg at 260 and 300 °C[145]. It was found that coarsened Si particles located at GBs strengthen the Al matrix through load transfer in the dislocation creep regime, thereby inhibiting GB sliding under low-stress conditions. As a result, the L-PBFed AlSi10Mg alloy exhibits creep resistance comparable to that of conventional cast alloys.

Nevertheless, although Sc/Zr modified Al alloys exhibit enhanced mechanical properties at ambient temperature, the high fraction of GBs significantly promotes rapid dynamic recovery and dislocation annihilation, further accelerating the creep rate and lowering the creep threshold stress[146]. For example, Griffiths et al. studied the precipitation-strengthened Al-Mg-Zr alloys prepared by L-PBF and highlighted this phenomenon[147]. The presence of a bimodal grain microstructure and GB precipitates in the as-fabricated alloy suggests that the dislocation motion and GB sliding constitute the dominant mechanisms governing creep behavior.

Surprisingly, recent advancements conducted by Zhang et al. have demonstrated impressive creep resistance in a novel Al-Mg alloy with a bimodal grain structure fabricated via AM multiscale microstructure tuning[148]. Despite the presence of UFGs, the alloy boasts low minimum strain rates of

To optimize creep resistance, current strategies frequently focus on tailoring the composition of novel eutectic-based alloys, enabling the formation of a high volume fraction of intermetallics with intrinsic coarsening resistance during the L-PBF process. For instance, the microstructural development and creep resistance of L-PBFed Al-Mn-Fe-Si-Zr alloy are investigated by Rakhmonov et al.[150]. The semi-coherent α-Al(FeMn)Si precipitates limit GB sliding and dislocation motion, resulting in a compressive threshold stress of 74 MPa at 300 °C. Furthermore, Michi et al. reported a new additively manufactured Al-Ce-Ni-Mn alloy that exhibits heterogeneity in precipitate distribution[107]. The results revealed that approximately

CONCLUSIONS AND OUTLOOK

Herein, this review systematically highlights the specific manifestations and formation mechanisms of microstructural heterogeneity in additively manufactured Al alloys, including grain structure, cellular structure, and phase distribution. We elaborate on the modulation strategies for heterogeneous microstructures by integrating alloy composition, L-PBF process, and heat treatment. More importantly, the remarkable impact of the heterostructure on mechanical properties is elucidated, particularly in terms of tensile, fatigue, and creep behaviors. Looking ahead, research on microstructural heterogeneity in AMed Al alloys can be further optimized in the following aspects.

(1) Development of novel Al alloys with advanced heterogeneous structures. Although AM techniques hold significant promise, the deliberate introduction of complex heterogeneous structures into Al alloys remains a persistent challenge due to the interplay of rapid solidification, melt pool dynamics, and solute redistribution. However, the inherent versatility of alloying elements and the multifaceted solidification conditions in L-PBF processes create unique opportunities for engineering tailored microstructural heterogeneity. By integrating thermodynamic software with advanced solidification modeling, researchers can now systematically design alloy compositions and refine processing parameters to predict and control solidification pathways, phase transformations, and solute partitioning behaviors. This synergistic approach not only enables precise manipulation of microstructural features - such as phase morphology, spatial distribution, and interfacial coherency - but also establishes a robust framework for enhancing the mechanical performance of L-PBF-fabricated Al alloys through heterostructure engineering. The combined control over composition and process variables thus represents a pivotal strategy for overcoming current limitations and advancing the structural integrity of AMed components under extreme service conditions.

(2) Investigation of emerging strategies for heterogeneous structure regulation. Leveraging the inherent advantages of diverse auxiliary fields (e.g., ultrasound, magnetism, etc.), field-assisted additive manufacturing (FAAM) has emerged as a powerful strategy for fabricating structural components with enhanced microstructural control. However, current research on laser powder bed fusion (L-PBF) primarily focuses on defect characterization, such as spatter formation, keyhole instability, porosity evolution, and melt pool turbulence, through X-ray imaging systems and fluid flow simulations[151,152], while the regulatory effects of auxiliary energy fields on microstructural heterogeneity remain underexplored. A promising alternative lies in the integration of laser shock peening (LSP) with L-PBF, where the additional thermal cycles generated by pulsed-wave lasers provide novel pathways for microstructure engineering in Al alloys[153,154]. This approach not only refines melt pool dynamics but also modulates phase nucleation and growth kinetics through localized energy input. Under the guidance of advanced computational strategies and process modeling, tailored heterogeneous structures can be systematically designed to optimize mechanical performance.

(3) Revealing the underlying mechanisms of heterostructured materials on mechanical properties. Over the past decade, the strategic incorporation of structural heterogeneity in AMed Al alloys has been demonstrated to significantly improve the strength-ductility synergy through the coexistence of hard and soft domains. This approach enables precise quantification of the HDI stress and effective stress via LUR experiments, offering critical insights into the mechanical behavior of these materials. However, the underlying mechanisms governing the interplay between hard and soft domains in fatigue and creep performance remain insufficiently comprehensive, particularly in terms of dislocation dynamics, phase boundary interactions, and solute segregation effects. Additionally, systematic evaluation methodologies to quantify the fatigue and creep resistance enhancements conferred by heterogeneous structures are still limited, hindering the full exploitation of their potential in high-performance applications. Addressing these gaps requires integrated experimental and computational frameworks that correlate microstructural features with macroscopic mechanical responses, thereby advancing the design of heterostructured Al alloys for AM.

(4) Elucidating the evolution mechanisms of heterogeneous structure under cyclic thermal loading. Thermal cycling is a critical factor in practical applications, especially for materials exposed to thermal fatigue and high-temperature environments. Although additively manufactured Al alloys with heterogeneous structures offer notable enhancements in strength and ductility, their performance under thermal cycling conditions becomes considerably more complex. These microstructural features strongly influence material performance, as they give rise to both favorable and potentially detrimental effects through thermal and mechanical interactions among phases and microregions. The mismatch in thermal expansion across different phases, grains, and cell walls may lead to stress concentration and failure initiation, particularly in materials characterized by pronounced microstructural heterogeneity. Therefore, these factors should be thoroughly considered in the design of materials intended for cyclic thermal loading applications. Further research will focus on a comprehensive investigation of these phenomena and the development of potential strategies to minimize the negative impacts of thermal cycling on heterogeneous structures.

DECLARATIONS

Authors’ contributions

Investigation, conceptualization and manuscript writing: Rong, Z.; Rong, X.

Supervision, editing and discussion: Rong, X.; Zhao, D.; Xu, Z.; Zhang, X.; Sha, J.; Shi, C.; He, C.; Zhao, N.

Manuscript review and finalization: Rong, X.; Zhao, D.; Shi, C.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Financial support and sponsorship

This work was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (2024YFA1209800), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (52201162, 52422103, and U23A20546), and the Natural Science Foundation of Tianjin (24JCQNJC00150).

Conflicts of interest

All authors declared that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026.

REFERENCES

2. Sun, W.; Zhu, Y.; Marceau, R.; et al. Precipitation strengthening of aluminum alloys by room-temperature cyclic plasticity. Science 2019, 363, 972-5.

3. Xue, H.; Yang, C.; De, Geuser. F.; et al. Highly stable coherent nanoprecipitates via diffusion-dominated solute uptake and interstitial ordering. Nat. Mater. 2023, 22, 434-41.

4. Raabe, D.; Tasan, C. C.; Olivetti, E. A. Strategies for improving the sustainability of structural metals. Nature 2019, 575, 64-74.

5. Xu, X.; Wu, G.; Tong, X.; et al. Achieving superior strength-ductility balance by tailoring dislocation density and shearable GP zone of extruded Al-Cu-Li alloy. Int. J. Plasticity. 2024, 182, 104135.

7. Liu, Z.; Meyers, M. A.; Zhang, Z.; Ritchie, R. O. Functional gradients and heterogeneities in biological materials: Design principles, functions, and bioinspired applications. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2017, 88, 467-98.

9. Hassanpour, H.; Jamaati, R.; Hosseinipour, S. J. A novel technique to form gradient microstructure in AA5052 alloy. Mater. Sci. Eng. A. 2020, 777, 139075.

10. Jiang, H.; Xing, H.; Xu, Z.; Feng, J.; Zhang, J.; Sun, B. Achieving superior strength-ductility balance in novel heterogeneous lamella structures of Al-Zn-Mg-Cu alloys. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2024, 184, 122-35.

11. Li, G.; Liu, M.; Lyu, S.; et al. Simultaneously enhanced strength and strain hardening capacity in FeMnCoCr high-entropy alloy via harmonic structure design. Scr. Mater. 2021, 191, 196-201.

12. Liu, J.; Liu, C.; Cai, H.; et al. Enhanced precipitate strengthening in particulates reinforced Al-Zn-Mg-Cu composites via bimodal structure design and optimum aging strategy. Compos. Part. B. Eng. 2023, 260, 110772.

13. Peng, Y.; Li, C.; Song, M.; et al. Breaking the strength-ductility trade-off in aluminum matrix composite through "dual-metal" heterogeneous structure and interface control. Int. J. Plasticity. 2025, 185, 104216.

14. Rong, X.; Zhao, D.; He, C.; Shi, C.; Liu, E.; Zhao, N. Revealing the strengthening and toughening mechanisms of Al-CuO composite fabricated via in-situ solid-state reaction. Acta. Mater. 2021, 204, 116524.

15. Zhang, Y.; Chen, R.; Hu, Y.; Wang, C.; Shen, Y.; Wang, X. Phase-specific tailoring strategy for synergetic and prolonged work hardening to achieve superior strength-plasticity in lamellar-structured alloy. Int. J. Plasticity. 2025, 188, 104317.

16. Nie, J.; Chen, Y.; Song, L.; et al. Enhancing strength and ductility of Al-matrix composite via a dual-heterostructure strategy. Int. J. Plasticity. 2023, 171, 103825.

17. Liu, L.; Li, S.; Pan, D.; et al. Loss-free tensile ductility of dual-structure titanium composites via an interdiffusion and self-organization strategy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2023, 120, e2302234120.

18. Zhang, X.; Yuan, H.; Huang, F.; et al. Enhanced strength-plasticity synergy of copper composites by designing uniformly dispersed yttria nanoparticles and a heterogeneous grain structure. Rare. Met. 2024, 43, 6704-16.

19. Xie, Y.; Lu, T.; Sun, B.; et al. Discontinuous precipitation enables an exceptional cryogenic strength-strain hardening synergy in a heterostructured medium entropy alloy. Acta. Mater. 2025, 290, 120955.

20. Li, X.; Lu, L.; Li, J.; Zhang, X.; Gao, H. Mechanical properties and deformation mechanisms of gradient nanostructured metals and alloys. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2020, 5, 706-23.

21. Zhu, Y.; Wu, X. Perspective on hetero-deformation induced (HDI) hardening and back stress. Mater. Res. Lett. 2019, 7, 393-8.

22. Shi, P.; Shen, Z.; Wang, H.; et al. Bioinspired, heredity-derived hierarchical bulk multifunctional copper alloys. Mater. Today. 2023, 71, 22-37.

23. Chen, H.; He, Y.; Dash, S. S.; Zou, Y. Additive manufacturing of metals and alloys to achieve heterogeneous microstructures for exceptional mechanical properties. Mater. Res. Lett. 2024, 12, 149-71.

24. Dong, X.; Gao, B.; Xiao, L.; et al. Heterostructured metallic structural materials: research methods, properties, and future perspectives. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2410521.

25. Ji, W.; Zhou, R.; Vivegananthan, P.; See, Wu. M.; Gao, H.; Zhou, K. Recent progress in gradient-structured metals and alloys. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2023, 140, 101194.

26. Wang, C.; Guo, M.; Chi, X.; Zhuang, L.; Niewczas, M. Dual gradient structure in Al-Zn-Mg-Cu-Fe alloys: a pathway to balancing strength and formability. Scr. Mater. 2025, 259, 116566.

27. Wu, R.; Choi, Y. T.; Wu, Q.; et al. Enhanced strength-ductility synergy in a gradient pseudo-precipitates heterostructured Al-2.5%Mg alloy: design, fabrication, and deformation mechanism. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2024, 196, 88-100.

28. Gu, D.; Shi, X.; Poprawe, R.; Bourell, D. L.; Setchi, R.; Zhu, J. Material-structure-performance integrated laser-metal additive manufacturing. Science 2021, 372, eabg1487.

29. Bandyopadhyay, A.; Traxel, K. D.; Lang, M.; Juhasz, M.; Eliaz, N.; Bose, S. Alloy design via additive manufacturing: advantages, challenges, applications and perspectives. Mater. Today. 2022, 52, 207-24.

30. Aboulkhair, N. T.; Simonelli, M.; Parry, L.; Ashcroft, I.; Tuck, C.; Hague, R. 3D printing of Aluminium alloys: additive manufacturing of aluminium alloys using selective laser melting. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2019, 106, 100578.

31. Yang, H.; Sha, J.; Zhao, D.; et al. Defects control of aluminum alloys and their composites fabricated via laser powder bed fusion: a review. J. Mater. Proc. Technol. 2023, 319, 118064.

32. Chua, C.; An, J.; Chua, C. K.; Kuo, C.; Sing, S. L. Microstructure control for inoculated high-strength aluminum alloys fabricated by additive manufacturing: a state-of-the-art review. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2025, 154, 101502.

33. Tan, Q.; Zhang, M. Recent advances in inoculation treatment for powder-based additive manufacturing of aluminium alloys. Mater. Sci. Eng. R. Rep. 2024, 158, 100773.

34. Huang, J.; Yang, W.; Gao, Z.; Hou, X.; Yan, X. Heterostructured multi-principal element alloys prepared by laser-based techniques. Microstructures 2025, 5, 2025021.

35. Deng, J.; Chen, C.; Liu, X.; Li, Y.; Zhou, K.; Guo, S. A high-strength heat-resistant Al-5.7Ni eutectic alloy with spherical Al3Ni nano-particles by selective laser melting. Scr. Mater. 2021, 203, 114034.

36. Qi, Y.; Zhang, H.; Yang, X.; et al. Achieving superior high-temperature mechanical properties in Al-Cu-Li-Sc-Zr alloy with nano-scale microstructure via laser additive manufacturing. Mater. Res. Lett. 2024, 12, 17-25.

37. Hyer, H.; Zhou, L.; Mehta, A.; et al. Composition-dependent solidification cracking of aluminum-silicon alloys during laser powder bed fusion. Acta. Mater. 2021, 208, 116698.

38. Wang, Y.; Li, R.; Yuan, T.; Zou, L.; Wang, M.; Yang, H. Microstructure and mechanical properties of Al-Fe-Sc-Zr alloy additively manufactured by selective laser melting. Mater. Charact. 2021, 180, 111397.

39. Tan, Q.; Yin, Y.; Prasad, A.; et al. Demonstrating the roles of solute and nucleant in grain refinement of additively manufactured aluminium alloys. Addit. Manuf. 2022, 49, 102516.

40. Cao, L.; Lu, R.; Dou, Z.; et al. Understanding the influence of high-strength submicron precipitate on the fracture performance of additively-manufactured aluminum alloy. Int. J. Plasticity. 2025, 188, 104306.

41. Agrawal, P.; Gupta, S.; Thapliyal, S.; Shukla, S.; Haridas, R. S.; Mishra, R. S. Additively manufactured novel Al-Cu-Sc-Zr alloy: microstructure and mechanical properties. Addit. Manuf. 2021, 37, 101623.

42. Thijs, L.; Kempen, K.; Kruth, J.; Van, Humbeeck. J. Fine-structured aluminium products with controllable texture by selective laser melting of pre-alloyed AlSi10Mg powder. Acta. Mater. 2013, 61, 1809-19.

43. Plotkowski, A.; Rios, O.; Sridharan, N.; et al. Evaluation of an Al-Ce alloy for laser additive manufacturing. Acta. Mater. 2017, 126, 507-19.

44. Wang, Z.; Lin, X.; Kang, N.; Hu, Y.; Chen, J.; Huang, W. Strength-ductility synergy of selective laser melted Al-Mg-Sc-Zr alloy with a heterogeneous grain structure. Addit. Manuf. 2020, 34, 101260.

45. Zhang, H.; Dai, D.; Yuan, L.; Liu, H.; Gu, D. Temperature gradient induced tough-brittle transition behavior of a high-strength