Translational insights into Duchenne muscular dystrophy: network biomarker identification and drug repositioning through multi-omics approaches

Abstract

Aim: Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) is a rare genetic condition that results in a lack of dystrophin protein due to a series of mutations. Current treatment strategies for DMD remain limited, highlighting the urgent need for novel therapeutic options. This study aimed to identify drugs that can be repositioned using DMD-specific molecular network signatures and potential diagnostic biomarkers, using a holistic, multi-omics data-integration approach.

Methods: We have examined messenger RNA expression datasets GSE109178, GSE70955, and GSE38417 to identify differentially expressed genes (DEGs) using adjusted P-value < 0.001 and |log2(fold change)| > 1 as the cut-off criteria. A total of 285 DEGs were identified as common across all three datasets. Principal component analyses were carried out using 33 hub genes identified from three-layered (protein-protein interaction, transcription factor, and microRNA) biological network constructions.

Results: The discrimination effect of these hub genes was found to be significantly higher between DMD patients and healthy controls. Therefore, these hub genes might be proposed as potential DMD-specific network biomarkers. Also, a drug repositioning analysis was conducted, revealing that celastrol, emetine dihydrochloride hydrate, radicicol, withaferin-A, and apigenin triacetate were reported as potential drugs for the management of DMD pathogenesis. The docking analysis with these repositioned drug candidates showed significant binding affinities among 17 network biomarkers (SQSTM1, PML, SPTAN1, SPTBN1, KIAA1429, SOX4, SP1, SPP1, NFKB1, TP53, NKX3-1, CIITA, ARL6IP1, IGFBP5, OCIAD2, RAP2B, and NFIB).

Conclusion: Celastrol and emetine dihydrochloride hydrate were the two repurposed small molecules that demonstrated effective docking results compared with inhibitors of hub genes and with the clinically used DMD-specific drug vamolorone. Further studies should be conducted to recapitulate these findings through in vitro and in vivo studies.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy (DMD), with an incidence of 1 in 3,000-5,000 male births, is an X-linked (Xp21.1) recessive neuromuscular disease characterized by dystrophin gene mutations that result in loss of function of the dystrophin protein[1]. The majority of mutations (about 60%) are deletions, while the remaining 40% include duplications and frameshift mutations[2]. These mutations occur in hotspot regions of the DMD gene, specifically exons 3-9 and 45-55[3-5].

The dystrophin protein provides an essential connection between the sarcolemmal cytoskeleton of muscle cells and the extracellular matrix, thereby preserving muscle function[6]. In the absence of dystrophin protein, the sarcolemma is damaged and membrane stabilization is disrupted, facilitating the entry of small molecules and calcium ions into the cell[6,7]. This causes increasing complications and pathological changes in muscle cell dysfunction and muscle cell fiber degeneration, eventually resulting in death[6,8]. DMD pathogenesis might cause some comorbidities such as gait disorders, difficulty in climbing stairs, scoliosis, cardiomyopathy, respiratory system disorders, and neurologic/neuropsychiatric problems[9]. Depending on the complications accompanying these disorders, the life expectancy of patients is approximately 20-30 years[8]. DMD has been generally diagnosed by biopsies, blood tests, and physical assessment to measure motor dysfunction.

Novel therapeutic developments rely on biomarkers that hold great promise for precise management strategies and provide potential disease indicators. Biomarkers used in blood tests for DMD diagnosis include inflammatory markers [e.g., cytokines such as interleukin-6 (IL-6)], microRNAs [miRNAs, such as muscle-specific miRNAs (myomiRs)], and metabolites (e.g., creatine kinase levels), which reflect myonecrosis in DMD[10,11]. Recent developments in DMD treatments include gene therapies, exon-skipping vaccines, drugs, genome-editing techniques, anti-inflammatory drugs, and corticosteroids to reduce symptoms[2,12,13]. Although these treatments reduce the course of the disease, they do not provide a complete cure because they cover only a certain percentage of mutations[14].

The majority of DMD-specific research published in the literature has used single-step omics data. Although recent DMD treatments generally focus on gene therapies, a comprehensive multi-omic approach may better uncover the molecular mechanisms of the disease by addressing the limitations of gene therapy-based strategies. Such an approach could provide a more advanced understanding of disease pathogenesis and therapeutic modalities. In this study, molecular networks integrating multi-omic data were constructed based on high-throughput transcriptome data to elucidate disease-specific biomarkers. Furthermore, the diagnostic power of the proposed biomarkers and the drug repositioning based on these disease signatures may provide a methodological illustration for addressing existing gaps in this field.

In this field, we identified 33 genes with the potential to serve as both network and diagnostic biomarkers for DMD. Among these genes, we found that 17 (SQSTM1, PML, SPTAN1, SPTBN1, KIAA1429, SOX4, SP1, SPP1, NFKB1, TP53, NKX3-1, CIITA, ARL6IP1, IGFBP5, OCIAD2, RAP2B, and NFIB) showed higher binding affinities to candidate repositioned drugs, including celastrol, radicicol, withaferin-A, emetine dihydrochloride hydrate, and apigenin triacetate. It is predicted that emetine dihydrochloride hydrate and celastrol may act synergistically in the management of DMD, given their essential roles in apoptosis, autophagy, anti-inflammatory responses, and infection-related pathways.

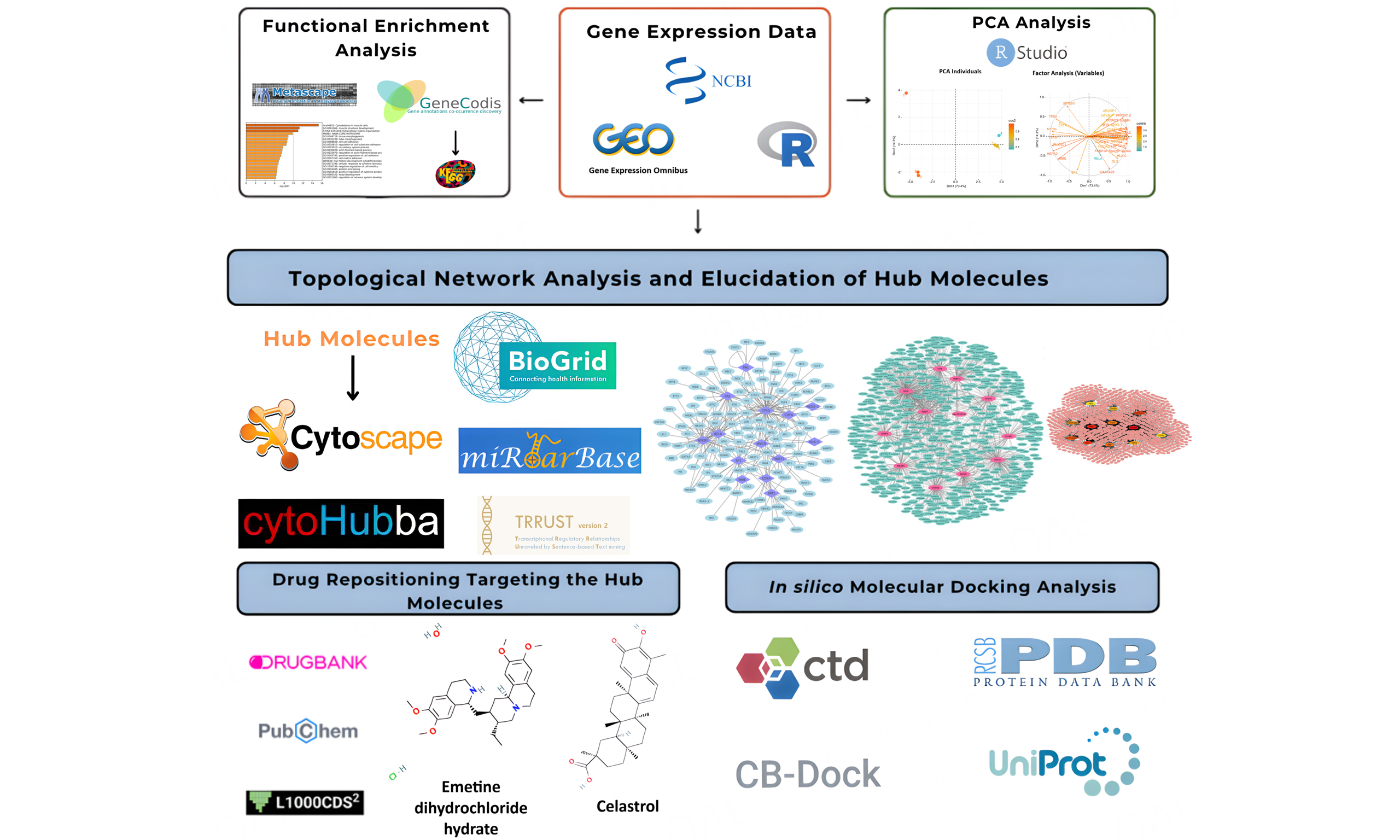

METHODS

Selection of datasets and identification of differentially expressed genes

The transcriptome-level data were searched through the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database with the keywords “DMD, Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy, microarray,” and the datasets with the accession numbers of GSE109178, GSE70955, and GSE38417 were retrieved[15,16]. The data, including six controls and 17 test groups for the GSE109178 dataset, three controls and 3 test groups for the GSE70955 dataset, and six controls and 16 tests for the GSE38317 dataset, were analyzed using GEO2R (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/geo2r/). For normalization, the Linear Models for Microarray Data (LIMMA) package was employed. Detailed information on the selected datasets is provided in Table 1. To determine the expression profiles of these DMD datasets, the cut-off values were adjusted to 0.001 and |log2FC| ≥ 1.0 for P-values and fold changes, respectively. Benjamini-Hochberg’s correction was employed to control the false discovery rate. Genes with log2FC > 1.0 were considered upregulated, whereas those with log2FC < -1.0 were classified as downregulated. The common differentially expressed genes (DEGs) across these three datasets were identified and used for further analysis.

DMD-specific datasets retrieved from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) at the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI)

| Accession number | Tissue | Study design | Platform |

| GSE38417 | Muscle | 16 DMD patients, six healthy controls | Affymetrix human genome U133 plus 2.0 array |

| GSE109178 | Muscle | 17 DMD patients, six healthy controls | Affymetrix human genome U133 Plus 2.0 array |

| GSE70955 | Muscle | 3 DMD patients, three healthy controls | Affymetrix human gene expression array |

Functional enrichment analysis

Common DEGs across 3 datasets (GSE38417, GSE70955, and GSE109178) were identified. These genes were used to enhance the understanding of biological pathways and functions around DEGs using Metascape, which assists in analyzing certain gene or protein lists to identify the biological processes, cellular constituents, or molecular activities associated with the genes or proteins[17]. The heatmap resulting from the analysis may indicate enriched biological pathways or processes[18].

Biological network constructions around DEGs

Three-layered biological network constructions were carried out by protein-protein interactions [PPIs; BioGrid (Biological General Repository for Interaction Datasets, thebiogrid.org)][19], miRNA-target DEG interactions (MiRTarBase, https://mirtarbase.cuhk.edu.cn/)[20], and transcription factor (TF)-target DEG interactions (TRRUST, http://www.grnpedia.org/trrust)[21]. Network constructions were conducted using Cytoscape 3.10.2[22]. The topological properties of these networks were analyzed using the CytoHubba plugin[23]. Hubs with the highest local and global topological parameters, including degree and betweenness centrality obtained from these three networks, were considered as DMD-specific network biomarkers and potential targets for drug repositioning.

Principal component analysis to establish diagnostic power of network signatures

To further assess whether network biomarkers can discriminate between the healthy and diseased states of the dataset samples, principal component analysis (PCA) was performed. R software version 4.3.2[24] and RStudio[25] were used for PCA. The “BiocManager” package was used to install the required Bioconductor dependencies, while the “factoextra” package was employed for visualization and interpretation of PCA results. The “prcomp” function was used to perform PCA based on the gene expression matrices. PCA was conducted separately for each dataset, using the expression values of each network signature. All PCAs were conducted using the normalized expression matrices produced by the limma workflow, in which expression values are mathematically adjusted for distributional differences and rendered directly comparable across samples. Importantly, the datasets were not merged for a unified PCA; instead, each dataset underwent PCA independently, and the clustering patterns were interpreted solely within its own sample space. Therefore, the input values used for PCA already represented variance-stabilized, scale-adjusted measures, eliminating the need for additional standardization beyond the limma normalization pipeline. The principal components explaining at least 70% of the total variance were considered in determining clustering performance, i.e., the ability to predict DMD. Hereupon, unless otherwise stated, these biomarkers will be accepted as potential diagnostic signatures of DMD.

For PCA-based discrimination analyses, sensitivity and specificity were computed using

where TP (True Positive) refers to DMD samples correctly clustered into the DMD group, FN (False Negative) represents DMD samples incorrectly clustered into the control group, TN (True Negative) signifies control samples correctly clustered into the control group, and FP (False Positive) refers to control samples incorrectly clustered into the DMD group.

Drug repositioning via targeting diagnostic biomarkers

To identify candidate drugs or small molecules that may play essential roles in disease pathogenesis, the 33 hub genes identified through network construction were investigated using L1000CDS2[26] based on their expression signatures. In the L1000CDS2 platform, the similarity between the DMD-associated gene expression signature and the drug-induced expression signatures is quantified using the cosine similarity metric (cosα). The value “1 - cosα” therefore represents the cosine distance between two signatures, with higher values indicating a stronger ability of the drug to reverse disease-associated gene expression patterns. Specifically, a larger 1 - cosα value reflects a more pronounced anti-correlation between the drug signature and the DMD signature, suggesting a greater potential for therapeutic reversal of the dysregulated pathways. The 50 potential repositioned drugs were identified and selected based on their 1-cosα values, U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval status, and limitations (e.g., the drug has many side effects; the chosen drug is an antineoplastic agent). Antibiotics, antifungals, anti-inflammatory agents, and anti-malarial drugs were selected considering the above-mentioned limitations. The mechanisms of action and indications of drugs were investigated using publicly available datasets from PubChem[27] and Drug Bank[28].

Molecular docking analysis to determine efficiency of repositioned drugs in silico

Protein Data Bank (PDB)[29] and UniProt[30] were used to select the structures of hub proteins. Protein structures were selected based on X-ray crystallography data with a resolution of ≤ 1.8 Å, as higher-resolution structures provide more accurate atomic positioning and improve the reliability of subsequent docking analyses. Inhibitors of each diagnostic biomarker were searched through the Comparative Toxicogenomics Database (CTD)[31] from the chemical-gene interaction section. The inhibitors were selected based on their ability to decrease the expression of the diagnostic biomarker genes. Three-dimensional structures of inhibitors and drugs were downloaded using PubChem[27]. The clinically used DMD medication vamolorone (VBP15) was also included in the screening pipeline to benchmark our candidate compounds. All ligands, including vamorolore, were subjected to the same preparation workflow and docked against the hub proteins using the CB-DOCK (cavity-detecting blind docking) blind docking platform[32]. This allowed direct comparison of binding affinities between FDA-approved therapeutic agents and the repositioned drug candidates identified in this study. Molecular docking analysis was performed using CB-Dock[32].

RESULTS

Identification of DEGs for DMD

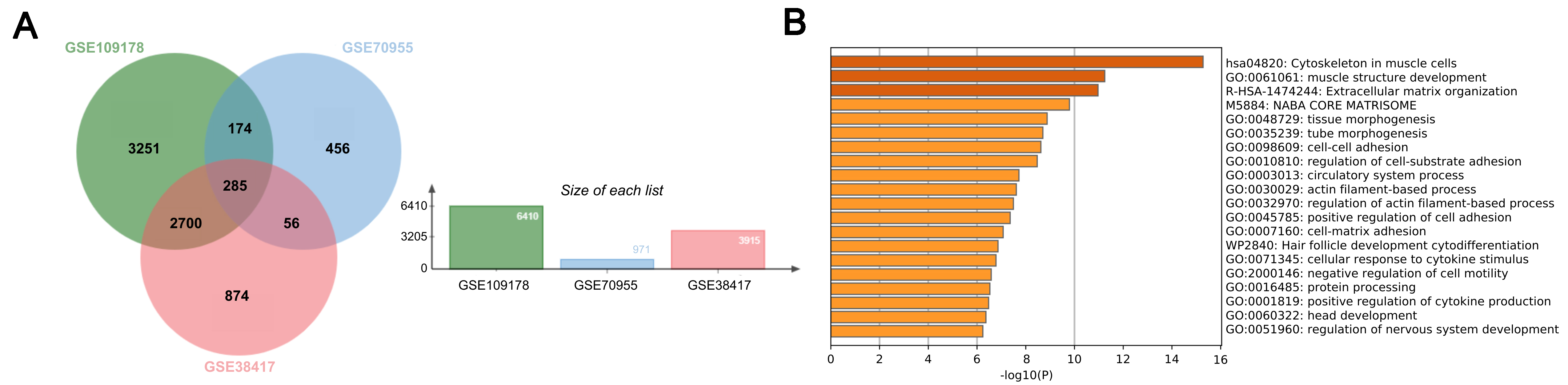

The datasets with accession numbers GSE70955, GSE38417, and GSE109178 were chosen for understanding the molecular mechanism of DMD at the transcriptome level. With the aid of GEO2R, the test and control groups for every set were established, and their differential expression was determined. The significance thresholds were set at a P-value < 0.001 and an |log2 fold change| ≥ 1.0. According to the differential expression analysis, 971 DEGs were identified in the GSE70955 dataset, 3,915 in the GSE38417 dataset, and 6,410 in the GSE109178 dataset. A comparison of the number of DEGs across the selected datasets shows that GSE109178 yielded the highest count. This dataset has a relatively large sample size, which increases statistical power, provides technical robustness, and leads to more genes reaching significance under a stringent threshold (P < 0.001, |log2FC| ≥ 1). The variation in the number of DEGs across the selected datasets may arise from differences in patient cohort characteristics - such as disease severity, age, muscle type biopsied, and treatment history - which collectively broaden or constrain overall transcriptional variability. Among the DEGs from the three datasets, overlapping genes were identified, resulting in 285 genes shared across all datasets [Figure 1A].

Functional enrichment analysis resulted in biological pathways that play crucial roles in pathogenesis

The common DEGs derived from specific datasets (GSE38418, GSE70955, and GSE109178) were functionally enriched and found to be significantly associated with extracellular matrix organization, muscle structure development, and cytoskeleton in muscle cells, as demonstrated by the Metascape results [Figure 1B]. Dark colors were used to express the first two processes, whereas less intense colors were used for the others. Darker hues often indicate more expressed genes or proteins, while lighter hues indicate less expressed ones[17].

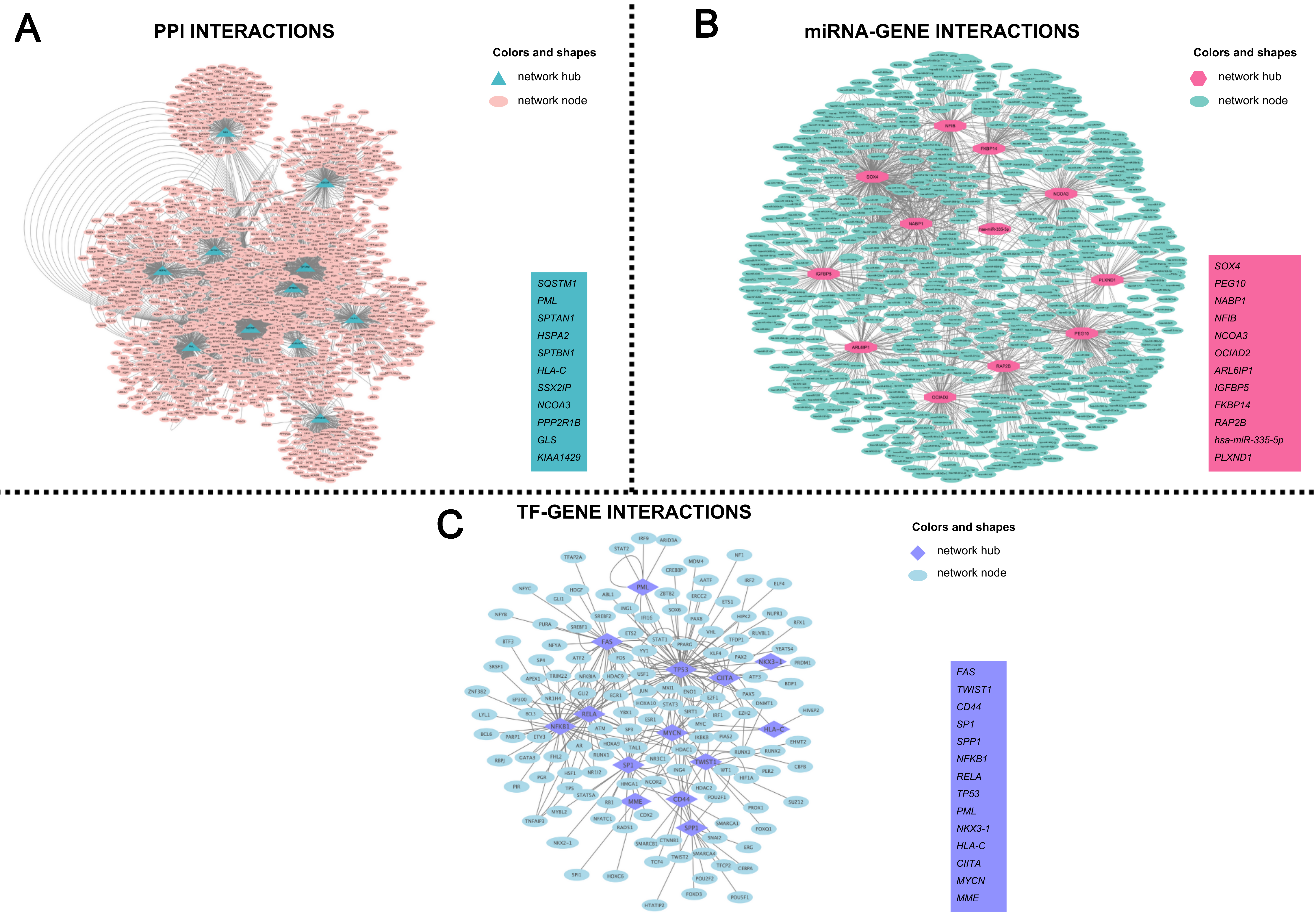

Networks constructions revealed DMD-specific molecular signatures

Network construction for DMD was performed using three different approaches: PPI, TF, and miRNA analyses. A total of 285 common DEGs identified from the GSE38417, GSE70955, and GSE109178 datasets were used. The PPI network comprised 1,739 nodes, 3,961 edges, and an average of 4,555 neighbors; the TF network included 94 nodes, 122 edges, and 2,596 average neighbors; and the miRNA network contained 2,189 nodes, 8,752 edges, and 6,095 average neighbors.

The PPI network was constructed using the BioGrid database. Topological analysis of the network identified the hubs with the highest degree and betweenness values: SQSTM1, PML, SPTAN1, HSPA2, SPTBN1, HLA-C, SSX2IP, NCOA3, PPP2R1B, GLS, and KIAA1429 [Figure 2A].

Figure 2. (A) PPI network constructed from the common differentially expressed genes (DEGs) identified across all datasets. Nodes represent proteins encoded by the DEGs, and edges denote experimentally validated or computationally supported protein–protein interactions obtained from the BioGRID database. Hub nodes (highlighted in teal triangular shapes) indicate proteins with the highest degree and betweenness centrality values, reflecting their central regulatory roles in the network. Non-hub nodes are shown in pink circular shapes. The inset lists the top-ranked PPI hubs prioritized for downstream analyses; (B) miRNA-gene interaction network visualizes microRNA - target gene relationships derived from the MiRTarBase database. Each pink triangular node represents a hub gene identified by network topology, whereas green circular nodes indicate miRNAs that interact with these targets. Edges represent experimentally validated miRNA-mRNA regulatory interactions. The inset summarizes the key miRNA-related hub signatures predicted to contribute to DMD-specific post-transcriptional regulation; (C) Transcription factor (TF)-gene regulatory network depicts TF-target interactions curated from the TRRUST database. Purple triangular nodes represent TF hubs exhibiting the highest centrality metrics, while blue circular nodes denote downstream target genes. Edges indicate known transcriptional regulatory relationships. The inset highlights TF hubs identified as key upstream regulators potentially driving the transcriptional architecture of DMD. DMD: Duchenne muscular dystrophy; PPI: protein-protein interaction.

The miRNA-target gene interactions were retrieved from the MiRTarBase database. Topological analysis considering degree and betweenness values identified the following hubs: SOX4, PEG10, NABP1, NFIB, NCOA3, OCIAD2, ARL6IP1, IGFBP5, FKBP14, RAP2B, hsa-miR-335-5p, PLXND1 [Figure 2B].

TF-target gene interactions were obtained from the TRRUST database to construct a transcriptional regulatory network. Topological analysis of this network, based on degree and betweenness values, identified the following hubs: FAS, TWIST1, CD44, SP1, SPP1, NFKB1, RELA, TP53, PML, NKX3-1, HLA-C, CIITA, MYCN, and MME [Figure 2C].

Together, these three network layers (PPI, miRNA, TF) provide a systems-level overview of the molecular interactions underlying DMD and highlight multi-omic regulatory hubs that serve as the basis for downstream biomarker identification and drug-repositioning analyses. The hub genes identified from these networks were considered the network signatures of DMD, and descriptions of each signature are provided in Table 2.

DMD-specific hubs of three-layered biological networks and their functions, inhibitor names, and UniProt IDs

| Gene name | UniProt ID | Regulation | Function | Inhibitor Name | Inhibitor PubChem ID | Ref |

| ARL6IP1 | Q15041 | UP | It plays a role in protein transport and cell signaling during hematopoietic maturation | Bisphenol A | 6623 | |

| CD44 | P16070 | UP | It is a hyaluronic acid receptor and plays a role in cell-cell crosstalk, cell adhesion, and cell migration | Acetaminophen | 1983 | [35] |

| CIITA | P33076 | UP | It controls MHC class I and II gene transcription that γ-interferon initiates | Melphalan | 460612 | [36] |

| FAS | P25445 | UP | It plays a central role in programmed cell death, cancer development, and progression | Alitretinoin | 449171 | |

| FKBP14 | Q9NWM8 | UP | It aids in procollagen folding, and defects in this gene can cause a type of Ehlers-Danlos syndrome | Deguelin | 1079352 | [39] |

| GLS | O94925 | UP | It encodes the K-type mitochondrial glutaminase, which is responsible for glutamine catabolism | Calcitriol | 5280453 | [40] |

| HLA-C | P10321 | UP | It functions as a ligand for killer immunoglobulin in receptors on natural killer cells and plays a role in the adaptive immune response | Lithocholic acid | 9903 | |

| HSPA2 | P54652 | DOWN | It encodes a chaperone protein, supports spermatogenesis, and facilitates the successful fertilization of oocytes | Aflatoxin B1 | 186907 | |

| IGFBP5 | P24593 | UP-DOWN | It promotes cell viability and the differentiation of muscle cells | Abrine | 160511 | |

| KIAA1429 | Q69YN4 | PPI | It regulates the migration and proliferation of endothelial cells in atherosclerosis | Bisphenol A | 6623 | [47] |

| MME | P08473 | UP-DOWN | The encoded protein is a neutral endopeptidase and functions as a cell surface marker in the diagnosis of acute lymphocytic leukemia | Fisetin | 5281614 | [48] |

| MYCN | P04198 | UP | It is essential for fetal development. Also, it is responsible for the regulation of gene expression, including proliferation, growth, apoptosis, energy metabolism, and differentiation | Ketamine-8 | 3812 | |

| NABP1 | Q96AH0 | UP | It is involved in DNA replication, recombination, and repair | Dronabinol | 16078B | [51] |

| NCOA3 | Q9Y6Q9 | UP | It regulates the progression of the cell cycle and functions as a transcriptional coactivator of NF-κB | Gambogic acid | 9852185 | [52] |

| NFIB | O00712 | UP | It encodes several developmental pathways involved in brain development, pons formation, and lung maturation | Aristolochic acid I | 2236A | [53] |

| NFKB1 | P19838 | TF | It regulates immediate-early response to viral infection, and inappropriate activation of NF-κB has been associated with many inflammatory diseases | Bisphenol A | 6623 | [54] |

| NKX3-1 | Q99801 | UP-DOWN | It acts as a transcription factor that functions critically in prostate development and tumor suppression | Isoflavones | 72304 | [55] |

| OCIAD2 | Q56VL3 | UP | It stimulates STAT3 activation and its phosphorylation, and cell motility | Endosulfan | 3224 | [56] |

| PEG10 | Q86TG7 | UP | It plays an important role in placenta formation and adipocyte differentiation. The dysregulated expression is associated with cell proliferation, apoptosis, and the development of malignancies | Azoxystrobin | 3034285P | [57] |

| PLXND1 | Q9Y4D7 | UP-DOWN | It encodes a protein involved in embryonic neurogenesis and vasculogenesis | Acrylamide | 6579 | [58] |

| PML | P29590 | UP | It regulates hemopoietic differentiation, cell growth, and tumorigenesis | Amphetamine | 3007 | [59] |

| PPP2R1B | P30154 | UP | It triggers tumor suppression by dephosphorylating the β-catenin pathway and plays an important role in cell cycle control | Bisphenol A | 6623 | [60] |

| RAP2B | P61225 | UP | It is the p53 target that mediates survival after DNA damage | Mitomycin | 5746 | [61] |

| RELA | Q04206 | TF | It regulates physiological processes, including cell proliferation, migration, and inflammation, and limits the induction of the IFN promoter at the posttranslational level in T cells | Melphalan | 460612 | [62] |

| SOX4 | Q06945 | UP | It is a crucial transcription factor for controlling progenitor development, differentiation, and stemness | Amitrole | 1639 | [63] |

| SP1 | P08047 | TF | It acts as a transcription factor, and its overexpression is linked to a worse prognosis in many types of cancer | Amitrole | 1639 | |

| SPP1 | P10451 | UP | It is involved in osteoclast binding to the mineralized bone matrix | Alandronate | 17684448 | [66] |

| SPTAN1 | Q13813 | UP | It functions as a pivotal scaffold protein that stabilizes the plasma membrane and organizes intracellular organelles | Acetaminophen | 1983 | [67] |

| SPTBN1 | Q01082 | UP-DOWN | It plays a role in determining cell shape and in regulating transmembrane proteins, cell adhesion, and cell migration | Amitrole | 1639 | [68] |

| SQSTM1 | Q13501 | UP-DOWN | Encoded protein controls the activation of the nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) signaling pathway and binds ubiquitin | 1,2- dimethylhydrazine | 1322 | [69] |

| SSX2IP | Q9Y2D8 | UP | It acts as a centrosome maturation factor and plays a role in the organization of cell-cell adherent junctions. | Levofloxacin | 149096 | [70] |

| TP53 | P04637 | TF | It is a tumor suppressor that plays a fundamental role in the development of cancer | Dust | 6433340 | [71] |

| TWIST1 | Q15672 | UP-DOWN | It regulates cell migration and proliferation during embryonic development | Benzo(a)pyrene | 2336 | [72] |

Principal component analysis unveiled predictive performance of network signatures

The network signatures indicated significantly different expression patterns between healthy controls and DMD patients. Clustering of samples based on these expression profiles, using the first principal component (PC1) from PCA (accounting for approximately 70% of the total variance) combined with the k-means algorithm, resulted in two clearly distinct sample subgroups. The total variance explained by PCA was 87.7% for GSE70955, 68.5% for GSE38417, and 69.9% for GSE109178. These results demonstrated that the diseased and control groups were well discriminated based on the expression patterns of the network signatures [Figure 3A-C]. The cos2 values reflected the contribution of each individual to the principal components, thereby indicating their relative importance in defining the multivariate structure. Higher values indicate a strong representation of the variables on the corresponding principal components, indicating that these components effectively capture their variance structure. Conversely, lower values suggest suboptimal representation, implying that the variables are not well explained by those components. Furthermore, sensitivity and specificity metrics of the identified network signatures were independently evaluated for each dataset to assess their discriminatory performance [Table 3]. The contributions of each network signature expression value were analyzed via factor analysis. As the highest contributors depending on expression values, OCIAD2, FAS, and HSPA2 genes in the GSE70955 dataset; FKBP14, CD44, and TWIST1 genes in the GSE38417 dataset; PLXND1, CD44, and GLS genes were found in the GSE109178 dataset [Figure 3A-C]. Across all three independent datasets, PCA shows that the identified network biomarkers exhibit a coherent variance structure that distinguishes DMD samples from healthy controls. The variable contribution maps further reveal gene-specific influences on clustering patterns, supporting the robustness and reproducibility of the identified biomarker signatures.

Figure 3. Principal Component Analysis (PCA) plots showing the discrimination of test and control groups for each dataset: (A) GSE38417, (B) GSE70955, and (C) GSE109178. Each panel presents two complementary PCA visualizations: (left) the distribution of individual samples and (right) the contribution of variables (network biomarkers) to the principal components. PCA was performed using limma-normalized gene expression matrices for each dataset, ensuring variance-stabilized and directly comparable values within each cohort. Left plots (PCA of individuals): Samples are projected onto the first two principal components (Dim 1 and Dim 2), with colors representing the cos2 values, which quantify the quality of representation of each sample in the PCA space. Higher cos2 values indicate that a sample is well explained by the selected components, whereas lower values reflect weaker representation. Separation patterns between healthy and DMD samples demonstrate the discriminatory capacity of the network signatures. Right plots (variable factor maps): Arrows correspond to individual biomarker genes, and their directions and lengths indicate the strength and orientation of each gene’s contribution to the PCA axes. The color gradient encodes the cos2 values, highlighting the variables that most strongly drive the variance structure. Longer vectors with high cos2 values represent biomarkers with greater influence on sample separation. The correlation circle delineates the multidimensional structure of gene-gene relationships within each dataset. DMD: Duchenne muscular dystrophy.

Sensitivity and specificity analyses of PCA results

| GSE38417 | GSE109178 | GSE70955 | |

| Number of controls | 6 | 6 | 3 |

| Number of patients | 16 | 17 | 3 |

| Sensitivity* | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Specificity** | 100 | 100 | 100 |

Drug repositioning analysis revealed candidate therapeutics for the management of DMD

The L1000CDS2 search engine was used to identify repositioned drug candidates targeting potential diagnostic biomarkers, using log2FC values for each as signature inputs. Using the genes and FC values of potential diagnostic biomarkers as input, we identified signatures and determined possible drug candidates that could reverse gene expression. A healthy state might have been achieved by reversing the expressions of each biomarker. The resulting drug candidates were ranked regarding 1-cosα values, which indicate overlap between input expression and drug-exposed controls in the LINCS (The Library of Integrated Network-Based Cellular Signatures, https://lincsproject.org/) database. The resultant 50 drugs were selected for further evaluation. Three criteria were applied to prioritize repositioned drugs: (i) preferably FDA approved, (ii) not originally indicated as antineoplastic agents to reduce side effects, and (iii) high 1-cosα values. Applying these criteria, five potential repositioned drugs or small molecules were identified: celastrol, radicicol, apigenin triacetate, emetine dihydrochloride hydrate, and withaferin-A. These drugs were comprehensively searched in PubChem, DrugBank, and the relevant literature. Their indications, mechanisms of action, approval statuses, and prior reports related to DMD are summarized in Table 4.

Repositioned drug candidates and their utilizations, mechanisms of action, and FDA approval statuses

| Perturbation | Indication | MOA | Approval status | Reference |

| Celastrol | Used for the treatment of inflammation and autoimmune disorders such as rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, nephritis, and asthma | Acts as an EC 5.99.1.3 [DNA topoisomerase (ATP-hydrolysing)] inhibitor and an Hsp90 inhibitor | Investigational | [73] |

| Radicicol | Exhibits anticancer activity and shows potential as an antitumor agent | Inhibits the heat shock protein 90 (HSP90), disrupting protein folding and stability | Investigational | [74,75] |

| Emetine dihydrochloride hydrate | Employed in the treatment of amebiasis, malaria, and SARS-CoV-2 infection | Inhibits eukaryotic protein synthesis by binding to the 40S ribosomal subunit and blocking the translocation step during translation | Approved | [76,77] |

| Withaferin-A | Demonstrates anti-tumor and anti-inflammatory effects, particularly in pancreatic and breast cancer therapies | Inhibits nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB), activates IκB kinase via a thiol alkylation-sensitive redox mechanism, induces apoptosis, and targets Hsp90 | Investigational, formerly FDA-approved | [78-80] |

| Apigenin triacetate | Associated with antifungal resistance in wheat and shows anticancer, neuroprotective, and antibacterial activities | Suppresses the development of Mycobacterium tuberculosis and exhibits neuroprotective effects in neurodegenerative diseases | Dietary supplements do not require extensive pre-marketing approval from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration | [81] |

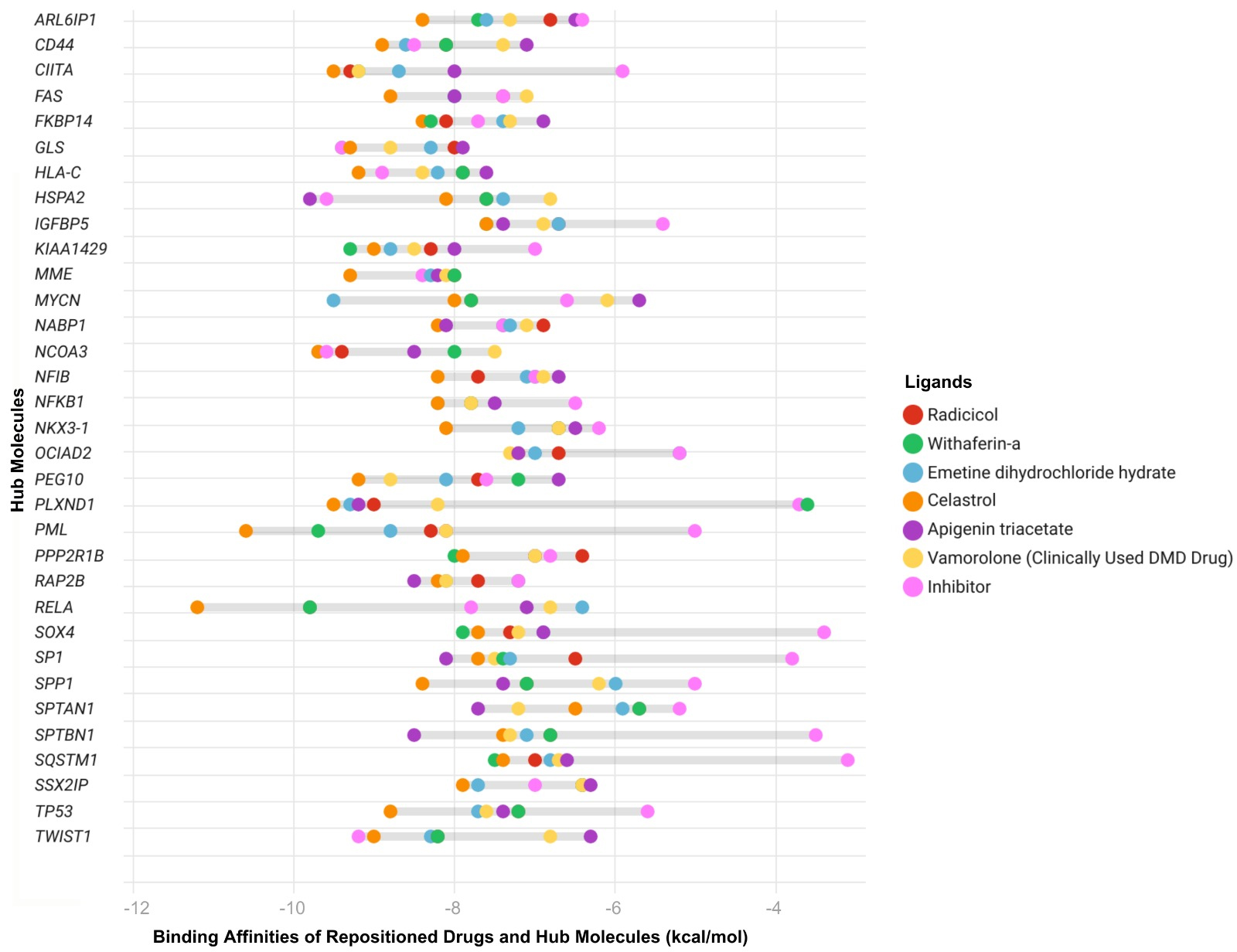

Molecular docking analysis indicated celastrol and emetine as in silico validated repositioned drug candidates

We performed molecular docking analyses to determine the interactions between selected drugs and DMD-specific diagnostic biomarkers. Binding affinities of inhibitors of these biomarkers were used as positive controls to evaluate the effectiveness of the selected drugs. Among the five drugs, celastrol (91%, n = 30 out of 33 network signatures), apigenin triacetate (67%, n = 22), radicicol (70%, n = 23), withaferin-A (73%, n = 24), and emetine dihydrochloride hydrate (emetine, 76%, n = 25) bound effectively to the biomarkers, comparable to the inhibitors [Figure 4]. Applying molecular docking simulations showed that 17 biomarkers (SQSTM1, PML, SPTAN1, SPTBN1, KIAA1429, SOX4, SP1, SPP1, NFKB1, TP53, NKX3-1, CIITA, ARL6IP1, IGFBP5, OCIAD2, RAP2B, and NFIB) out of 33 network signatures bound to the repositioned drugs better than their inhibitors and showed better binding affinities compared with the inhibitors. Comparing all repositioned drugs analyzed by docking, celastrol and emetine demonstrated better binding affinities for the proposed DMD biomarkers [Figure 4]. Emetine is an FDA-approved drug with anti-malarial and anti-protozoal effects, and celastrol is an investigational drug with antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects. These drugs were found to bind well to DMD biomarkers. The docking results demonstrated that the binding affinities of the network-derived candidate compounds - particularly celastrol and emetine - were generally more favorable (i.e., more negative docking energies) toward the DMD-specific diagnostic biomarkers compared with vamolorone. These findings indicate that the proposed candidates exhibit stronger predicted interactions with multiple key hub proteins than the clinically used reference drug.

Figure 4. Predicted binding affinities of ligands - including hub inhibitors, the clinically used DMD-specific drug vamolorone, and repositioned drugs - were assessed by molecular docking analysis. Each drug is represented by a different color. Binding energies were calculated using CB-Dock, with more negative values indicating stronger predicted ligand-protein interactions. Each point represents the docking score for a specific hub protein - ligand pair. The Y-axis shows the most central network biomarkers identified through integrated PPI, TF, and miRNA network analyses, representing key regulatory molecules implicated in DMD pathogenesis. The X-axis lists the same hub proteins. DMD: Duchenne muscular dystrophy; PPI: protein-protein interaction; CB-Dock: cavity-detecting blind docking.

DISCUSSION

DMD is a rare and progressive neuromuscular condition caused by an X-linked mutation resulting in the loss of the protein dystrophin. DMD patients have a reduced life expectancy, with a reported median survival of 22.0 years {95% confidence interval [CI], 21.2-22.4}[82].

The existing mainstay treatment is based on corticosteroids for reducing symptoms and inflammation[12]; however, they do not provide a complete cure. The recent FDA-approved treatment modalities cover utrophin modulation to increase protein expression, and transfer of micro/mini dystrophins designed from gene therapies with adeno-associated virus vector by skipping exon 50-52 (etepliersen)[14], skipping exon-53 (golodirsen and viltolarsen)[2]. Using antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs) is another recently studied technique that enables exon skipping, with studies targeting exons 51, 53, 45, and 44 currently ongoing[13]. Although these drugs and treatments hold promise for DMD patients, full therapeutic effects might not be achieved, as they address only a small subset of disease-causing mutations. In addition, the production costs of ASOs and the challenges of precise targeted delivery pose significant hurdles for their clinical application[83]. Preclinical research is still ongoing due to the risk of off-target effects and unintended mutations[84]. Therefore, there is an urgent unmet need for the development of new therapeutics that can overcome these limitations, potentially through the integration of multi-omics data to identify all molecular players involved in disease progression.

The costs and development time of new treatments are major limitations for researchers and patients struggling with rare diseases. This challenge can be significantly alleviated by state-of-the-art systems, advances in biomedicine, and drug-repositioning approaches using drugs already on the market. Drug repositioning appears to be a promising strategy because it offers a unique way to identify new effects of approved drugs more quickly, at lower cost, and with shorter clinical trial periods. This approach has been and continues to be applied to a wide range of diseases[85].

In this study, DMD was evaluated by integrating transcriptome-level data with network biology approaches to identify new drug candidates, including celastrol, radicicol, apigenin triacetate, emetine dihydrochloride hydrate, and withaferin-A, which have been suggested as potential therapeutics through in silico validations for DMD management. The construction of DMD-specific biological networks at three molecular levels - TFs, miRNAs, and proteins - allowed us to assess the most essential hubs of the disease that carry the information flow potentially responsible for pathogenesis [Figure 2A-C]. These 33 hubs were defined as “network signatures of DMD” and further evaluated for their predictive performance in distinguishing healthy from disease samples using PCA. They demonstrated significant effects in clustering healthy samples and DMD patients, with 100% sensitivity and 100% specificity [Table 3 and Figure 3]. Network signature-based drug repositioning revealed drugs with the potential to reverse gene expression patterns [Table 4]. We selected approved or investigational drugs, including celastrol, apigenin triacetate, emetine dihydrochloride hydrate, withaferin-A, dipyridamole, and radicicol. Some of these compounds were reported to have antineoplastic effects [Table 4]. All these small molecules are discussed comprehensively in subsequent sections.

Radicicol (monorden) is isolated from the fungus Monosporium bonorden and is known as an antibiotic[86]. Radicicol, a powerful sedative with a low toxicity rate, was first identified as a protein tyrosine kinase inhibitor, and later its heat shock protein 90 (Hsp90) inhibitory activity was revealed[75]. Since Hsp90 affects the growth of many oncogenic proteins, its inhibition leads to the shutdown of multiple pathways involved in cancer[87,88]. As a result of drug repositioning research, radicicol became one of 19 drugs that provide rapid inhibition against Naegleria fowleri[89]. Radicicol has also been reported as a repositioned drug candidate for breast cancer and coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)[90,91].

As an ayurvedic herb, Ashwagandha (Withania somnifera) contains a steroidal lactone called withaferin-A. It is well-known for its anti-inflammatory, anti-tumorigenic, and anti-carcinogenic activities[92-94]. It is typically utilized for patients with other unexplained gynecological malignancies, as well as lung, breast, ovarian, colorectal, prostate, gastrointestinal, cervical, and hematological cancers[93,94]. Beyond these diseases, withaferin-A has demonstrated potential as a treatment for conditions such as osteoarthritis, Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer’s disease, and cystic fibrosis[95]. By preventing nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) activation and disrupting the CDC37-Hsp90 complex, withaferin-A has the potential to be used as a therapeutic drug in the treatment of cancer, hematological malignancies, and chronic inflammatory disorders[96]. Overactivity of NF-κB results in the loss and disruption of muscle cells, whereas withaferin-A-induced NF-κB suppression can promote the development of new myofibers and may be useful in DMD treatment[97]. Currently, no study in the literature has reported DMD treatment with withaferin-A.

Apigenin, naturally produced by Thymelaeaceae, Verbenaceae, and Selaginellaceae plants, is a flavonoid component[98]. It exhibits anti-spasmodic, anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, anti-cancer (osteosarcoma, prostate, bladder, liver, and colorectal cancer cells), and antiproliferative properties[99,100]. Apigenin also has strong antiviral activity, as it inhibits Mpro, the primary SARS-CoV-2 (severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2) protease, thereby blocking the virus’s ability to replicate[101]. By modulating integrin signaling pathways and downregulating Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) target genes

Celastrol (tripterine) is a compound obtained from the Tripterygium wilfordii (Thunder God Vine) plant and is widely used in Chinese medicine. It has anti-inflammatory properties and has shown potential as a drug in many autoimmune diseases, including rheumatoid arthritis (RA), systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), allergy, inflammatory bowel disease, ankylosing spondylitis, osteoarthritis[105-107], and metabolic diseases such as obesity and diabetes[108]. Celastrol has also been studied in leukemia, glioma, and prostate cancer, as it prevents tumor cell proliferation through its anticancer properties by inhibiting the NF-κB pathway via limiting IκBα degradation, blocking p65 translocation, and reducing MMP-9 production[105,109]. Celastrol induces heat shock protein 70 (Hsp70), an important chaperone protein involved in cytoprotection, protein folding, and repair in non-muscle cells[110]. It has also been studied for neurodegenerative disorders such as Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s diseases. The effect of celastrol on Parkinson’s disease was investigated using the Drosophila DJ-1A model, and it was found to boost dopamine levels, prevent dopaminergic neuron death, and alleviate locomotor dysfunction[111]. A bioinformatics study found a link between NR1D2 gene expression and mitochondrial quality control, with mitochondrial dysfunction contributing to DMD. Docking analysis between the NR1D2 gene and celastrol suggested that celastrol could be used to treat colorectal muscular atrophy[112]. Celastrol has also been repurposed for the treatment of breast cancer, COVID-19, and human papillomavirus (HPV)18-based cervical cancer[113-115]. Celastrol has not previously been reported as a repositioned drug for the treatment of DMD.

Emetine, or emetine dihydrochloride hydrate, is an isoquinoline alkaloid and an antiprotozoal drug obtained from the alizarin family of the Carapichea ipecacuanha species[116,117]. Emetine, an FDA-approved small molecule, has been used to treat amoebic liver abscesses, malaria, and intestinal infections[77]. It is effective in inhibiting protein synthesis in mammalian cells. Emetine has been reported to disrupt messenger RNA (mRNA)-eIF4E interactions and is therefore proposed as an effective compound for inhibiting viral polymerases[116]. It induces apoptosis by regulating apoptotic factors[118]. Drug repositioning of emetine dihydrochloride hydrate has previously been explored for antimalarial drug trials, Alzheimer’s disease, SARS-CoV-2, breast cancer, and squamous cell carcinoma[77,119]. Emetine dihydrochloride hydrate/emetine has not previously been reported as a repositioned drug for the treatment of DMD.

All these drugs may have the potential to exert therapeutic effects on DMD. Among these five drugs, celastrol and emetine exhibited the highest binding affinities, with percentages of 91% (n = 30 out of 33 DMD biomarkers) and 76% (n = 25 out of 33 DMD biomarkers), respectively. These drugs bind effectively to genes including SQSTM1, PML, SPTAN1, SPTBN1, KIAA1429, SOX4, SP1, SPP1, NFKB1, TP53, NKX3-1, CIITA, ARL6IP1, IGFBP5, OCIAD2, RAP2B, and NFIB, which are involved in inflammation, infection, autophagy, and apoptosis-related biological processes. Therefore, celastrol is proposed as an efficient candidate, either alone or in combination with emetine. Together, they may exert a synergistic effect in managing DMD by enhancing anti-inflammatory responses, reducing oxidative stress, inducing apoptosis, and promoting the scavenging activities of the drugs. The possible mechanisms of action of celastrol are detailed in the following sections.

Celastrol was reported to increase SIRT3 gene expression, which is associated with oxidative stress and has an inflammation-lowering effect[120]. Another study reported that the absence of dystrophin in DMD pathogenesis leads to oxidative stress[121]. In this regard, celastrol might be considered to have an oxidative stress-reducing effect in DMD. It has been observed that pro-inflammatory cytokine levels controlled by NF-κB, examined in dystrophic muscles of DMD patients, are expressed at much higher levels than normal[122]. Inhibiting NF-κB promotes muscle regeneration in DMD[123]. Additionally, in biopsies from Crohn’s disease patients, celastrol suppressed the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, especially tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α)[124]. Celastrol functions as an immunomodulatory agent to minimize excessive inflammation by modulating TNF-α and IL-6[125]. Celastrol’s well-characterized ability to modulate NF-κB signaling, suppress pro-inflammatory cytokines, and attenuate oxidative stress[105,126] is directly linked to the chronic inflammation and ROS accumulation that drive muscle degeneration in DMD. The hub genes identified in our network - such as NFKB1, RELA, SPP1, SP1, and HSPA2 - are central regulators in these pathways, suggesting a direct mechanistic alignment between celastrol’s pharmacodynamics and the molecular signatures disrupted in DMD. Celastrol also induces heat shock responses, enhances chaperone expression [heat shock proteins (HSPs)], and modulates autophagy[127,128]. Given that impaired proteostasis and defective muscle regeneration are hallmark features of DMD, these molecular effects provide a biologically plausible rationale for celastrol’s therapeutic potential, particularly through modulating SQSTM1, HSPA2, and GLS, which emerged as key nodes in our network analysis. Therefore, celastrol is proposed to hold great promise for DMD patients by alleviating effects on NF-κB signaling, inflammation, and oxidative stress responses.

Emetine, by contrast, influences a complementary set of DMD-relevant pathways. Its ability to inhibit protein synthesis under cellular stress, regulate apoptosis, and modulate the integrated stress response[76] intersects with core degenerative mechanisms observed in dystrophic muscle, including mitochondrial dysfunction, excessive apoptotic signaling, and endoplasmic reticulum stress. Additionally, emetine has been reported to exert anti-inflammatory effects and reduce fibrosis-related gene expression[77], processes that are highly pertinent to the fibrotic remodeling and immune dysregulation that characterize late-stage DMD pathology. Together, these drug-specific mechanisms map directly onto the molecular signatures uncovered by our integrated PPI, miRNA, and TF networks - particularly through hubs such as SPP1, CD44, MYCN, HLA-C, CIITA, and PML - highlighting how both compounds may modulate multiple interconnected biological processes central to DMD progression.

Overall, by integrating curated pharmacological evidence with network-level molecular disruptions, our findings provide a coherent mechanistic rationale linking celastrol and emetine to the inflammatory, oxidative, regenerative, and proteostatic abnormalities that define DMD. These results not only strengthen the biological plausibility of our computational predictions but also offer a focused set of hypotheses for future experimental validation in DMD cellular and animal models.

DMD is a rare and clinically heterogeneous disorder for which comprehensive multi-omics datasets remain limited, and this scarcity inevitably constrains the breadth and depth of computational investigations. In this study, DMD was examined through the integration of transcriptome-derived molecular signatures and network-level biomarkers, followed by in silico drug repositioning analyses targeting these diagnostic nodes. Although this systems-based framework provides a valuable hypothesis-generating platform, several important limitations should be acknowledged to contextualize the conclusions drawn from the findings. The analyses depend entirely on publicly available transcriptome-level datasets, which, while enabling broad molecular profiling, lack the granularity and biological control offered by experimental models. Publicly archived datasets often differ in sample collection protocols, tissue processing methods, sequencing platforms, and normalization strategies, all of which may introduce technical variability that cannot be fully eliminated even with rigorous normalization and quality control. Despite employing variance-stabilized, limma-normalized expression matrices to reduce such heterogeneity, the limited availability of matched omics datasets for DMD restricts the capacity to capture the full molecular spectrum of the disease. The absence of age- and sex-matched samples further complicates interpretation, as developmental stage and biological sex are known to influence dystrophic muscle phenotypes and inflammatory responses. Even though the combined sample size across datasets allows for statistically meaningful comparisons, the overall omics landscape might be more accurately resolved through additional datasets encompassing broader demographic and clinical diversity. The computationally predicted biomarker signatures and drug-target interactions represent theoretical inferences grounded in transcriptomic and network-derived associations. These predictions cannot be regarded as confirmatory in the absence of functional validation. DMD patient-derived myoblasts, induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC)-derived muscle models, and well-established animal models such as the mdx mouse would provide the mechanistic context necessary to validate the regulatory importance of the identified biomarkers and to test the biological efficacy of the proposed drug candidates. The lack of experimental evaluation limits the capacity to fully infer whether the predicted modulatory effects would manifest in physiological settings. The drug repositioning strategy implemented here focuses predominantly on inhibitory interactions, which biases the analysis toward regulators of inflammation, immune activation, and fibrosis that are typically upregulated in dystrophic muscle. This targeted emphasis may overlook compounds with activation potential capable of restoring pathways related to muscle regeneration, mitochondrial bioenergetics, or metabolic homeostasis. The restricted scope of screening may therefore underrepresent the therapeutic potential of drugs that act through upregulatory mechanisms. The molecular docking simulations provide structural insight into potential ligand-protein interactions; however, docking remains an approximation that does not account for conformational flexibility, dynamic cellular environments, pharmacokinetic constraints, or drug metabolism. Protein dynamics, post-translational modifications, and tissue-specific isoforms may influence binding in vivo in ways that cannot be fully represented through static docking models.

Despite these limitations, the study establishes a coherent computational framework capable of uncovering biologically meaningful targets and generating testable hypotheses for therapeutic development. The integration of network biomarkers, transcriptomic perturbation signatures, and ligand-target affinity modeling provides a foundation for future investigations that combine in silico predictions with cellular and animal validation studies. A key direction for subsequent work involves confirming whether the in silico predictions translate into measurable phenotypic improvements in experimental DMD models and exploring whether activation-based therapeutics could complement the inhibitory mechanisms identified here.

CONCLUSION

DMD is a rare and challenging disease, as there is no complete cure. In this study, omics-oriented network constructions were performed to integrate transcriptome-level data and multi-omic crosstalk in the pathogenesis of DMD. The identified biomarkers were used as targets to reverse the gene expression signatures of DMD via drug repositioning. Two repositioned drug candidates, emetine dihydrochloride hydrate and celastrol, were reported as potential therapeutic agents for the management of DMD. Emetine dihydrochloride hydrate, a potent plant-derived alkaloid, and celastrol, a bioactive compound derived from plants, exhibited promising pharmacological properties according to docking results. These findings demonstrate the significant therapeutic potential of these phytochemical-derived compounds and reinforce the importance of phytochemicals as a foundation for novel drug development in modern medicine.

DECLARATIONS

Authors’ contributions

Made substantial contributions to drafting the work, methodology, and visualization: Parmak HB, İyisoy ME, Unal Z, Eskicubuk H

Made substantial contributions to methodology, software development, data curation, and visualization: Okutan K

Made substantial contributions to conceptualization, methodology, validation, software development, data curation, visualization, supervision, and writing - review & editing: Aydin B.

All authors contributed to the original draft and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Financial support and sponsorship

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used in this study are publicly available in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database at the following links: GSE38417- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE38417, GSE109178- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE109178, GSE70955- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE70955. Additional data related to this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of interest

All authors declared that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2025.

REFERENCES

1. Chiu W, Hsun YH, Chang KJ, et al. Current genetic survey and potential gene-targeting therapeutics for neuromuscular diseases. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21:9589.

2. Duan D, Goemans N, Takeda S, Mercuri E, Aartsma-Rus A. Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2021;7:13.

3. Patterson G, Conner H, Groneman M, Blavo C, Parmar MS. Duchenne muscular dystrophy: current treatment and emerging exon skipping and gene therapy approach. Eur J Pharmacol. 2023;947:175675.

4. Roberts TC, Wood MJA, Davies KE. Therapeutic approaches for Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2023;22:917-34.

5. Suzuki H, Aoki Y, Kameyama T, et al. Endogenous multiple exon skipping and back-splicing at the DMD mutation hotspot. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17:1722.

6. Chang M, Cai Y, Gao Z, et al. Duchenne muscular dystrophy: pathogenesis and promising therapies. J Neurol. 2023;270:3733-49.

7. Bez Batti Angulski A, Hosny N, Cohen H, et al. Duchenne muscular dystrophy: disease mechanism and therapeutic strategies. Front Physiol. 2023;14:1183101.

8. Ryder S, Leadley RM, Armstrong N, et al. The burden, epidemiology, costs and treatment for Duchenne muscular dystrophy: an evidence review. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2017;12:79.

9. Qian C, Klimchak AC, Szabo SM, Popoff E, Iannaccone ST, Gooch KL. Observing the clinical course of Duchenne muscular dystrophy in medicaid real-world healthcare data. Adv Ther. 2024;41:2519-30.

10. Grounds MD, Terrill JR, Al-Mshhdani BA, Duong MN, Radley-Crabb HG, Arthur PG. Biomarkers for Duchenne muscular dystrophy: myonecrosis, inflammation and oxidative stress. Dis Model Mech. 2020;13:dmm043638.

11. Szigyarto C. Duchenne muscular dystrophy: recent advances in protein biomarkers and the clinical application. Expert Rev Proteomics. 2020;17:365-75.

12. Shieh PB. Emerging strategies in the treatment of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Neurotherapeutics. 2018;15:840-8.

13. Reinig AM, Mirzaei S, Berlau DJ. Advances in the treatment of Duchenne muscular dystrophy: new and emerging pharmacotherapies. Pharmacotherapy. 2017;37:492-9.

14. Lim KR, Maruyama R, Yokota T. Eteplirsen in the treatment of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2017;11:533-45.

15. Dadgar S, Wang Z, Johnston H, et al. Asynchronous remodeling is a driver of failed regeneration in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. J Cell Biol. 2014;207:139-58.

16. Choi IY, Lim H, Estrellas K, et al. Concordant but varied phenotypes among Duchenne muscular dystrophy patient-specific myoblasts derived using a human iPSC-based model. Cell Rep. 2016;15:2301-12.

17. Zhou Y, Zhou B, Pache L, et al. Metascape provides a biologist-oriented resource for the analysis of systems-level datasets. Nat Commun. 2019;10:1523.

18. Merico D, Isserlin R, Stueker O, Emili A, Bader GD. Enrichment map: a network-based method for gene-set enrichment visualization and interpretation. PLoS One. 2010;5:e13984.

19. Oughtred R, Rust J, Chang C, et al. The BioGRID database: a comprehensive biomedical resource of curated protein, genetic, and chemical interactions. Protein Sci. 2021;30:187-200.

20. Huang HY, Lin YC, Cui S, et al. miRTarBase update 2022: an informative resource for experimentally validated miRNA-target interactions. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022;50:D222-30.

21. Han H, Shim H, Shin D, et al. TRRUST: a reference database of human transcriptional regulatory interactions. Sci Rep. 2015;5:11432.

22. Shannon P, Markiel A, Ozier O, et al. Cytoscape: a software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res. 2003;13:2498-504.

23. Chin CH, Chen SH, Wu HH, Ho CW, Ko MT, Lin CY. cytoHubba: identifying hub objects and sub-networks from complex interactome. BMC Syst Biol. 2014;8 (Suppl 4):S11.

24. R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. 2013. Available from https://cran.r-project.org/bin/windows/base/ [Last accessed on 29 Dec 2025].

25. RStudio Team. RStudio: Integrated development environment for R. 2020. Available from https://posit.co/download/rstudio-desktop/ [Last accessed on 29 Dec 2025].

26. Duan Q, Reid SP, Clark NR, et al. L1000CDS2: LINCS L1000 characteristic direction signatures search engine. npj Syst Biol Appl. 2016;2:16015.

28. Wishart DS, Knox C, Guo AC, et al. DrugBank: a knowledgebase for drugs, drug actions and drug targets. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:D901-6.

29. Berman HM, Westbrook J, Feng Z, et al. The protein data bank. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:235-42.

30. The UniProt Consortium. UniProt: the universal protein knowledgebase in 2023. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023;51:D523-31.

31. Davis AP, Wiegers TC, Johnson RJ, Sciaky D, Wiegers J, Mattingly CJ. Comparative toxicogenomics database (CTD): update 2023. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023;51:D1257-62.

32. Liu Y, Grimm M, Dai WT, Hou MC, Xiao ZX, Cao Y. CB-Dock: a web server for cavity detection-guided protein-ligand blind docking. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2020;41:138-44.

33. Akiduki S, Ikemoto MJ. Modulation of the neural glutamate transporter EAAC1 by the addicsin-interacting protein ARL6IP1. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:31323-32.

34. Lim JH, Kang HM, Kim DH, et al. ARL6IP1 gene delivery reduces neuroinflammation and neurodegenerative pathology in hereditary spastic paraplegia model. J Exp Med. 2024;221:e20230367.

35. Ritchie KE, Nör JE. Perivascular stem cell niche in head and neck cancer. Cancer Lett. 2013;338:41-6.

36. Devaiah BN, Singer DS. CIITA and its dual roles in MHC gene transcription. Front Immunol. 2013;4:476.

37. Comi C, Leone M, Bonissoni S, et al. Defective T cell fas function in patients with multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2000;55:921-7.

38. Cao Y, Miao XP, Huang MY, et al. Polymorphisms of death pathway genes FAS and FASL and risk of nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Mol Carcinog. 2010;49:944-50.

39. Aldeeri AA, Alazami AM, Hijazi H, Alzahrani F, Alkuraya FS. Excessively redundant umbilical skin as a potential early clinical feature of Morquio syndrome and FKBP14-related Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. Clin Genet. 2014;86:469-72.

40. Aledo JC, Gómez-Fabre PM, Olalla L, Márquez J. Identification of two human glutaminase loci and tissue-specific expression of the two related genes. Mamm Genome. 2000;11:1107-10.

41. Blais ME, Dong T, Rowland-Jones S. HLA-C as a mediator of natural killer and T-cell activation: spectator or key player? Immunology. 2011;133:1-7.

42. Vollmers S, Lobermeyer A, Körner C. The new kid on the block: HLA-C, a key regulator of natural killer cells in viral immunity. Cells. 2021;10:3108.

43. Nowicka-Bauer K, Malcher A, Włoczkowska O, Kamieniczna M, Olszewska M, Kurpisz MK. Evaluation of seminal plasma HSPA2 protein as a biomarker of human spermatogenesis status. Reprod Biol. 2022;22:100597.

44. Mohanty G, Jena SR, Kar S, Samanta L. Paternal factors in recurrent pregnancy loss: an insight through analysis of non-synonymous single-nucleotide polymorphism in human testis-specific chaperone HSPA2 gene. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2022;29:62219-34.

45. Cobb LJ, Salih DA, Gonzalez I, et al. Partitioning of IGFBP-5 actions in myogenesis: IGF-independent anti-apoptotic function. J Cell Sci. 2004;117:1737-46.

46. Ren H, Yin P, Duan C. IGFBP-5 regulates muscle cell differentiation by binding to IGF-II and switching on the IGF-II auto-regulation loop. J Cell Biol. 2008;182:979-91.

47. Rong J, Jie Y, Zhao H. m6A ‘writer’ KIAA1429 regulates the proliferation and migration of endothelial cells in atherosclerosis. Mol Biotechnol. 2023;65:1198-206.

48. Choi WW, Weisenburger DD, Greiner TC, et al. A new immunostain algorithm classifies diffuse large B-cell lymphoma into molecular subtypes with high accuracy. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:5494-502.

49. Henriksson M, Luscher B. Proteins of the Myc network: essential regulators of cell growth and differentiation. Adv Cancer Res. 1996;68:109-82.

51. Lawson T, El-Kamand S, Boucher D, et al. The structural details of the interaction of single-stranded DNA binding protein hSSB2 (NABP1/OBFC2A) with UV-damaged DNA. Proteins. 2020;88:319-26.

52. Lira MC, Rosa FD, Aiello I, et al. NCoA3 upregulation in breast cancer-associated adipocytes elicits an inflammatory profile. Oncol Rep. 2023;49:105.

53. Steele-Perkins G, Plachez C, Butz KG, et al. The transcription factor gene Nfib is essential for both lung maturation and brain development. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:685-98.

54. Biswas R, Bagchi A. NFkB pathway and inhibition: an overview. Comput Mol Biol. 2016;6:1. Available from: https://bioscipublisher.com/index.php/cmb/article/view/2268. [Last accessed on 25 Dex 2025].

55. Papachristodoulou A, Heidegger I, Virk RK, et al. Metformin overcomes the consequences of NKX3.1 loss to suppress prostate cancer progression. Eur Urol. 2024;85:361-72.

56. Sinha S, Bheemsetty VA, Inamdar MS. A double helical motif in OCIAD2 is essential for its localization, interactions and STAT3 activation. Sci Rep. 2018;8:7362.

57. Xie T, Pan S, Zheng H, et al. PEG10 as an oncogene: expression regulatory mechanisms and role in tumor progression. Cancer Cell Int. 2018;18:112.

58. Glass GE, Mohammedali S, Sivakumar B, et al. Poland-Möbius syndrome: a case report implicating a novel mutation of the PLXND1 gene and literature review. BMC Pediatr. 2022;22:745.

59. Wang ZG, Delva L, Gaboli M, et al. Role of PML in cell growth and the retinoic acid pathway. Science. 1998;279:1547-51.

60. Zhu Y, Loukola A, Monni O, et al. PPP2R1B gene in chronic lymphocytic leukemias and mantle cell lymphomas. Leuk Lymphoma. 2001;41:177-83.

61. Zhang X, He Y, Lee KH, et al. Rap2b, a novel p53 target, regulates p53-mediated pro-survival function. Cell Cycle. 2013;12:1279-91.

62. Jeremiah N, Ferran H, Antoniadou K, et al. RELA tunes innate-like interferon I/III responses in human T cells. J Exp Med. 2023;220:e20220666.

64. Citron BA, Saykally JN, Cao C, Dennis JS, Runfeldt M, Arendash GW. Transcription factor Sp1 inhibition, memory, and cytokines in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Neurodegener Dis. 2015;4:40-8.

66. McKee MD, Cole WG. Chapter 2 - Bone Matrix and Mineralization. In: Glorieux FH, Pettifor JM, Jüppner HBT-PB, editors. Pediatric bone. San Diego: Elsevier; 2012. pp. 9-37.

67. Goodman SR, Johnson D, Youngentob SL, Kakhniashvili D. The spectrinome: the interactome of a scaffold protein creating nuclear and cytoplasmic connectivity and function. Exp Biol Med. 2019;244:1273-302.

68. Tang W, Shao Q, He Z, Zhang X, Li X, Wu R. Clinical significance of nonerythrocytic spectrin Beta 1 (SPTBN1) in human kidney renal clear cell carcinoma and uveal melanoma: a study based on pan-cancer analysis. BMC Cancer. 2023;23:303.

70. Breslin A, Denniss FA, Guinn BA. SSX2IP: an emerging role in cancer. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;363:462-5.

71. Aubrey BJ, Strasser A, Kelly GL. Tumor-suppressor functions of the TP53 pathway. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2016;6:a026062.

72. Shelton EL, Yutzey KE. Twist1 function in endocardial cushion cell proliferation, migration, and differentiation during heart valve development. Dev Biol. 2008;317:282-95.

73. Song X, Zhang Y, Dai E, Du H, Wang L. Mechanism of action of celastrol against rheumatoid arthritis: a network pharmacology analysis. Int Immunopharmacol. 2019;74:105725.

74. Hesterkamp T, Whittaker M. Fragment-based activity space: smaller is better. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2008;12:260-8.

75. Sano M. Radicicol and geldanamycin prevent neurotoxic effects of anti-cancer drugs on cultured embryonic sensory neurons. Neuropharmacology. 2001;40:947-53.

76. Jiménez A, Carrasco L, Vázquez D. Enzymic and nonenzymic translocation by yeast polysomes. Site of action of a number of inhibitors. Biochemistry. 1977;16:4727-30.

77. Matthews H, Usman-Idris M, Khan F, Read M, Nirmalan N. Drug repositioning as a route to anti-malarial drug discovery: preliminary investigation of the in vitro anti-malarial efficacy of emetine dihydrochloride hydrate. Malar J. 2013;12:359.

78. Xing Z, Su A, Mi L, et al. Withaferin a: a dietary supplement with promising potential as an anti-tumor therapeutic for cancer treatment - pharmacology and mechanisms. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2023;17:2909-29.

79. Hahm ER, Kim SH, Singh SV. Withaferin A inhibits breast cancer-induced osteoclast differentiation. Mol Carcinog. 2023;62:1051-61.

80. Patra JK, Das G, Lee S, Kang S, Shin H. Selected commercial plants: a review of extraction and isolation of bioactive compounds and their pharmacological market value. Trends Food Sci Technol. 2018;82:89-109.

81. Deshaies M, Lamari N, Ng CKY, Ward P, Doohan FM. The impact of chitosan on the early metabolomic response of wheat to infection by Fusarium graminearum. BMC Plant Biol. 2022;22:73.

82. Broomfield J, Hill M, Guglieri M, Crowther M, Abrams K. Life expectancy in Duchenne muscular dystrophy: reproduced individual patient data meta-analysis. Neurology. 2021;97:e2304-14.

83. Matsuo M. Antisense oligonucleotide-mediated exon-skipping therapies: precision medicine spreading from Duchenne muscular dystrophy. JMA J. 2021;4:232-40.

84. Wasala NB, Hakim CH, Chen SJ, Yang NN, Duan D. Questions answered and unanswered by the first CRISPR editing study in a canine model of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Hum Gene Ther. 2019;30:535-43.

85. Zhao B, Wang L, Hu P, et al. Fusing higher and lower-order biological information for drug repositioning via graph representation learning. IEEE Trans Emerg Topics Comput. 2024;12:163-76.

86. Agatsuma T, Ogawa H, Akasaka K, et al. Halohydrin and oxime derivatives of radicicol: synthesis and antitumor activities. Bioorg Med Chem. 2002;10:3445-54.

87. Schulte TW, Akinaga S, Murakata T, et al. Interaction of radicicol with members of the heat shock protein 90 family of molecular chaperones. Mol Endocrinol. 1999;13:1435-48.

88. Zhou H, Qiao K, Gao Z, Vederas JC, Tang Y. Insights into radicicol biosynthesis via heterologous synthesis of intermediates and analogs. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:41412-21.

89. Rice CA, Colon BL, Chen E, Hull MV, Kyle DE. Discovery of repurposing drug candidates for the treatment of diseases caused by pathogenic free-living amoebae. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2020;14:e0008353.

90. Islam T, Rahman MR, Aydin B, Beklen H, Arga KY, Shahjaman M. Integrative transcriptomics analysis of lung epithelial cells and identification of repurposable drug candidates for COVID-19. Eur J Pharmacol. 2020;887:173594.

91. Turanli B, Karagoz K, Bidkhori G, et al. Multi-omic data interpretation to repurpose subtype specific drug candidates for breast cancer. Front Genet. 2019;10:420.

92. Sail V, Hadden MK. Chapter eighteen - notch pathway modulators as anticancer chemotherapeutics. Annu Rep Med Chem. 2012;47:267-80.

93. Dutta R, Khalil R, Green R, Mohapatra SS, Mohapatra S. Withania somnifera (Ashwagandha) and withaferin a: potential in integrative oncology. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20:5310.

94. Straughn AR, Kakar SS. Withaferin a: a potential therapeutic agent against COVID-19 infection. J Ovarian Res. 2020;13:79.

95. Das R, Rauf A, Akhter S, et al. Role of Withaferin a and its derivatives in the management of alzheimer’s disease: recent trends and future perspectives. Molecules. 2021;26:3696.

96. Berghe W, Sabbe L, Kaileh M, Haegeman G, Heyninck K. Molecular insight in the multifunctional activities of Withaferin A. Biochem Pharmacol. 2012;84:1282-91.

97. Radzka J, Łapińska Z, Szwedowicz U, Gajewska-Naryniecka A, Gizak A, Kulbacka J. Alternations of NF-κB signaling by natural compounds in muscle-derived cancers. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24:11900.

98. Zhang W, Zhuang X, Wu C, et al. Apigenin inhibits tumor angiogenesis by hindering microvesicle biogenesis via ARHGEF1. Cancer Lett. 2024;596:216961.

99. Dormán G, Flachner B, Hajdú I, András C. Target identification and polypharmacology of nutraceuticals. In: Gupta RC, Lall R, Srivastava A, Editors. Nutraceuticals. Elsevier Inc.; 2016. pp. 263-86.

100. Jantan I, Haque MA, Arshad L, Harikrishnan H, Septama AW, Mohamed-Hussein ZA. Dietary polyphenols suppress chronic inflammation by modulation of multiple inflammation-associated cell signaling pathways. J Nutr Biochem. 2021;93:108634.

101. Yang M, Lin L, Scartelli C, et al. Inhibition of Sars-Cov-2 viral replication and in vivo thrombus formation by a novel plant flavonoid. Blood. 2021;138:3144.

103. Laoudj-Chenivesse D, Carnac G, Bisbal C, et al. Increased levels of adenine nucleotide translocator 1 protein and response to oxidative stress are early events in facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy muscle. J Mol Med. 2005;83:216-24.

104. Hangül C, Karaüzüm SB, Akkol EK, et al. Promising perspective to facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy treatment: nutraceuticals and phytochemicals. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2021;19:2276-95.

105. Sethi G, Ahn KS, Pandey MK, Aggarwal BB. Celastrol, a novel triterpene, potentiates TNF-induced apoptosis and suppresses invasion of tumor cells by inhibiting NF-κB-regulated gene products and TAK1-mediated NF-κB activation. Blood. 2007;109:2727-35.

106. Cohen TV, Cohen JE, Partridge TA. Myogenesis in dysferlin-deficient myoblasts is inhibited by an intrinsic inflammatory response. Neuromuscul Disord. 2012;22:648-58.

107. Cascão R, Fonseca JE, Moita LF. Celastrol: a spectrum of treatment opportunities in chronic diseases. Front Med. 2017;4:69.

108. Xu S, Feng Y, He W, et al. Celastrol in metabolic diseases: progress and application prospects. Pharmacol Res. 2021;167:105572.

109. Wang Z, Zhai Z, Du X. Celastrol inhibits migration and invasion through blocking the NF-κB pathway in ovarian cancer cells. Exp Ther Med. 2017;14:819-24.

110. Gwag T, Ha K, Shin H, et al. Application of a heat shock protein inducer to remedy for an atrophied muscle cell: a basic research for ISS/JEM onboard experiment. Trans JSASS Aerospace Tech Japan. 2014;12:Pp_7-Pp_10.

111. Faust K, Gehrke S, Yang Y, Yang L, Beal MF, Lu B. Neuroprotective effects of compounds with antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties in a Drosophila model of Parkinson’s disease. BMC Neurosci. 2009;10:109.

112. Wu M, Zhang Y. Integrated bioinformatics, network pharmacology, and artificial intelligence to predict the mechanism of celastrol against muscle atrophy caused by colorectal cancer. Front Genet. 2022;13:1012932.

113. Kori M, Arga KY, Mardinoglu A, Turanli B. Repositioning of anti-inflammatory drugs for the treatment of cervical cancer sub-types. Front Pharmacol. 2022;13:884548.

114. Jadamba E, Shin M. A systematic framework for drug repositioning from integrated omics and drug phenotype profiles using pathway-drug network. Biomed Res Int. 2016;2016:7147039.

115. Fuzo CA, Martins RB, Fraga-Silva TFC, et al. Drug repurposing to face Covid-19: Celastrol, a potential leading drug capable of inhibiting SARS-CoV-2 replication and induced inflammation. bioRxiv. 2021;bioRxiv:2021.04.20.439992.

116. Kumar R, Khandelwal N, Chander Y, et al. Emetine as an antiviral agent suppresses SARS-CoV-2 replication by inhibitinginteraction of viral mRNAwith eIF4E: an in vitro study. bioRxiv. 2020;bioRxiv:2020.11.29.401984.

117. Wang X, Li M, Yin J, et al. Emetine dihydrochloride alleviated radiation-induced lung injury through inhibiting EMT. J Cell Mol Med. 2023;27:3839-50.

119. Savva K, Zachariou M, Bourdakou MM, Dietis N, Spyrou GM. Network-based stage-specific drug repurposing for Alzheimer’s disease. Comput Struct Biotechnol J. 2022;20:1427-38.

120. Wang Y, Li C, Gu J, et al. Celastrol exerts anti-inflammatory effect in liver fibrosis via activation of AMPK-SIRT3 signalling. J Cell Mol Med. 2020;24:941-53.

121. Petrillo S, Pelosi L, Piemonte F, et al. Oxidative stress in Duchenne muscular dystrophy: focus on the NRF2 redox pathway. Hum Mol Genet. 2017;26:2781-90.

122. Messina S, Vita GL, Aguennouz M, et al. Activation of NF-κB pathway in Duchenne muscular dystrophy: relation to age. Acta Myol. 2011;30:16-23.

123. Donovan J, Elvire Vandenborne KH, Sweeney L, et al. Move DMD results: effects of edasalonexent, an NF-kB inhibitor, in 4 to 7 year old patients with Duchenne Muscular dystrophy (P3.210). Neurology. 2017;88:P3.210.

124. Pinna GF, Fiorucci M, Reimund JM, Taquet N, Arondel Y, Muller CD. Celastrol inhibits pro-inflammatory cytokine secretion in Crohn’s disease biopsies. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;322:778-86.

125. Khalili N, Karimi A, Moradi MT, Shirzad H. In vitro immunomodulatory activity of celastrol against influenza a virus infection. Immunopharmacol Immunotoxicol. 2018;40:250-5.

126. Cascão R, Vidal B, Raquel H, et al. Effective treatment of rat adjuvant-induced arthritis by celastrol. Autoimmun Rev. 2012;11:856-62.

127. Trott A, West JD, Klaić L, et al. Activation of heat shock and antioxidant responses by the natural product celastrol: transcriptional signatures of a thiol-targeted molecule. Mol Biol Cell. 2008;19:1104-12.

Cite This Article

How to Cite

Download Citation

Export Citation File:

Type of Import

Tips on Downloading Citation

Citation Manager File Format

Type of Import

Direct Import: When the Direct Import option is selected (the default state), a dialogue box will give you the option to Save or Open the downloaded citation data. Choosing Open will either launch your citation manager or give you a choice of applications with which to use the metadata. The Save option saves the file locally for later use.

Indirect Import: When the Indirect Import option is selected, the metadata is displayed and may be copied and pasted as needed.

About This Article

Special Topic

Copyright

Data & Comments

Data

Comments

Comments must be written in English. Spam, offensive content, impersonation, and private information will not be permitted. If any comment is reported and identified as inappropriate content by OAE staff, the comment will be removed without notice. If you have any queries or need any help, please contact us at support@oaepublish.com.