CNT array-based aluminum bipolar electrode iontronic memristors

Abstract

Iontronics has emerged as a compelling platform for neuromorphic computing, where ions serve as functional charge carriers for information processing. Iontronic memristors hold particular promise due to their ability to emulate synaptic signal transmission through history-dependent ion transport. However, most existing devices rely on delicate control of nanochannel geometry and surface chemistry to induce ionic hysteresis, posing challenges for tunability and scalable materials design. Here, we introduce an alternative route to ionic memristive behavior based on asymmetric electrochemical reactions occurring at the poles of a bipolar electrode (BPE). In this system, a carbon nanotube array (ACNT) membrane selectively regulates cation transport on one side of an aluminum BPE, dynamically modifying local reaction environments and producing voltage-dependent enhancement or suppression of the redox current. This coupling between ion-selective nanochannels and reaction kinetics yields pronounced rectification and hysteretic current-voltage responses without requiring precise adjustment of nanoscale confinement. The ACNT-based- aluminum device further mimics short-term synaptic plasticity, demonstrating its capability for neuromorphic emulation. This electrochemically driven strategy establishes a versatile materials framework in which diverse redox chemistries and ion-regulating layers can be combined to construct tunable, solution-operable iontronic memristors.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

Iontronic memristors are promising candidates for brain-like neuromorphic computing to model the processing and memory functions of synapses and neurons[1,2]. Among various ionic systems, nanofluidic devices featuring nanoscale pores, channels, or slits[3-8] are particularly significant, as they uncover the fundamental mechanisms of ion transport regulation in aqueous environments. In these nanofluidic devices, the hysteresis of ion transport, which is the intrinsic property of memristors, relies on the strong interaction between mobile ions and the electric double layer (EDL) at the solid-liquid interface[9-11]. To achieve hysteresis in ion transport behavior, a strong-confinement structure and high-density surface charges are required[12-14]. For instance, in (sub) nanoscale 2D slits, the conduction changes occur through the assembling or breaking of nonconducting Bjerrum pairs, or their clustering into conducting arcs[15-17]. Additionally, high charge density - either from inner wall charges or from modified polyelectrolytes in asymmetric nanochannels - can lead to ion accumulation or depletion, further contributing to the hysteretic changes in conduction[18-22]. These advances in nanofluidic devices have significantly grounded our understanding of ionic transport regulation[3,23]. However, the approaches that rely on channel geometry and interfacial surface modification offer limited tunability of ion transport in nanoconfined environments. Consequently, expanding the modulation range, achieving effective amplification, and enabling scalable integration remain challenges for nanofluidic memristors.

A bipolar electrode (BPE) is a conductive material that drives electrochemical reactions at its poles when immersed in an electrolyte and subjected to an applied voltage[24,25]. This induces oxidation at one pole and reduction at the other, enabling reactions without direct electrical contact. Additionally, it is known that the kinetics of these electrochemical reactions are determined by the ion diffusion rate and the charge transfer efficiency at the electrode interface[26]. Building upon the ion regulation mechanisms in previous nanofluidic research, the integration of BPEs can introduce a new dimension of control through employing the intrinsically sluggish kinetics of electrochemical reactions, rather than relying solely on precise control of interfacial properties and geometrical features at the nanoscale[27]. In addition, the driving force arising from the spontaneous reaction can generate hysteresis even at relatively high ion migration rates, greatly enhancing the tuning freedom of ion transport. Meanwhile, the cooperative regulation enabled by electrochemical reactions reduces the strict dependence on nanoscale channel structures and interfacial properties, thereby facilitating scaling and integration of the device. Together, such nanofluidic/ electrochemical architectures provide new inspiration for dynamic tuning strategies to develop iontronic memristors.

In this work, we demonstrate a carbon nanotube array (ACNT) membrane-based aluminum (Al) BPE. Compared to Al foil serving as a closed BPE, which generates symmetrical redox currents under opposite voltage due to similar reaction conditions at both poles, the cation-selective multichannel ACNT membrane at one pole can selectively modulate ion transport on that side and introduce a controlled asymmetry in the electrochemical reaction conditions. This asymmetry, combined with the intrinsically sluggish kinetics of the redox reactions, enables pronounced diode-like memristive characteristics of hysteresis and rectification. Importantly, this design eliminates the strict nanoscale precision required in nanofluidic devices and proposes a versatile, programmable platform where ionic conductance can be tuned through both ion transport and electrochemical reaction dynamics. Such a strategy offers a new approach to constructing scalable and tunable iontronic memristors for neuromorphic computing applications.

EXPERIMENTAL

Materials

High-purity Al foil (~2 mm × 2 mm, 20 μm thick) was purchased from Anhui Zhengying Technology Co., Ltd., China. Bisphenol A epoxy resin (EP) was purchased from Nantong Xingchen Synthetic Material Co., Ltd., China. Polyamide resin was purchased from Dingyuan County Danbao Resin Co., Ltd., China. Dibutyl phthalate was purchased from Aladdin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd., China.

Fabrication of ACNT membrane

First, a piece of ACNT was deposited on a silicon wafer (~15 mm × 15 mm) according to the previously reported method[28]. The obtained ACNT was treated with a vacuum plasma cleaner (TS-PL05, Tonson Tec Technology Co., Ltd., China) under an oxygen atmosphere for surface activation. Next, polyamide resin, EP, and dibutyl phthalate were mixed at a mass ratio of 1:0.9:0.72 and thoroughly stirred to form a polymer precursor solution, which was then degassed in a vacuum oven (DZG-6020, Shanghai Sumsung Experimental Instrument Co., Ltd., China) to remove air bubbles. Subsequently, the treated ACNT was placed into a square acrylic mold and fully immersed in the degassed polymer solution, which was further degassed and maintained under vacuum for about 40 min to eliminate bubbles trapped between CNTs, followed by curing at 60 °C for 3 h under ambient pressure to obtain a bulk composite. After demolding and trimming excess EP, the composite was embedded in molten paraffin using a biological tissue embedding machine (KD-BM, Zhejiang Jinhua Kedi Instrumental Equipment Co., Ltd., China) and rapidly cooled on a cryogenic plate (KD-BL, Zhejiang Jinhua Kedi Instrumental Equipment Co., Ltd., China). Finally, the paraffin-embedded composite was sectioned into flexible ACNT membranes (~20 μm thick) using a manual rotary microtome (RM2235, Leica Biosystems, Germany). A simplified schematic of the fabrication process is shown in Supplementary Figure 1.

Characterizations

The surfaces of the ACNT membrane and Al foil were examined using a desktop field emission scanning electron microscope (SEM) equipped with energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) (Phenom Pharos G2, Phenom, Netherlands), operated at acceleration voltages of 10 and 5 kV, respectively. Wettability was characterized using an optical contact angle measuring instrument (OCA100, Dataphysics, Germany). Water contact angles of the untreated Al foil and the ACNT membrane (before and after plasma treatment) were measured, and each value was averaged from three measurements at different surface positions using a 3 μL droplet of deionized water. The zeta potentials of the ACNT membrane and Al foil were determined using an electrokinetic analyzer (SurPASSTM 3, Anton Paar, Austria), based on the streaming current generated by an electrolyte solution (1 mM KCl, pH ≈ 5.7) flowing along the sample surface.

Experimental setup

A 20 mM KCl aqueous solution was prepared by dissolving KCl in deionized water and subsequently diluted to obtain solutions of different concentrations. The ACNT membrane and Al foil were mounted between homemade two-compartment cells, which consisted of an aluminum alloy substrate, two square polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA) containers, and a rotating push pole. Two Ag/AgCl electrodes were separately placed in the two compartments, with the working electrode on the side of the Al foil. Current-voltage (I-V) experiments were performed using triangular waveforms (amplitudes of ±1.0 or ±1.5 V) on an electrochemical workstation (CHI 660E, Shanghai CH Instruments, Inc., USA) to analyze electrochemical performance. All experiments were conducted in a Faraday cage to minimize interference from external electromagnetic fields. Bar charts with error bars were plotted and analyzed using Origin (OriginLab, USA).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

ACNT/Al BPE iontronic memristors

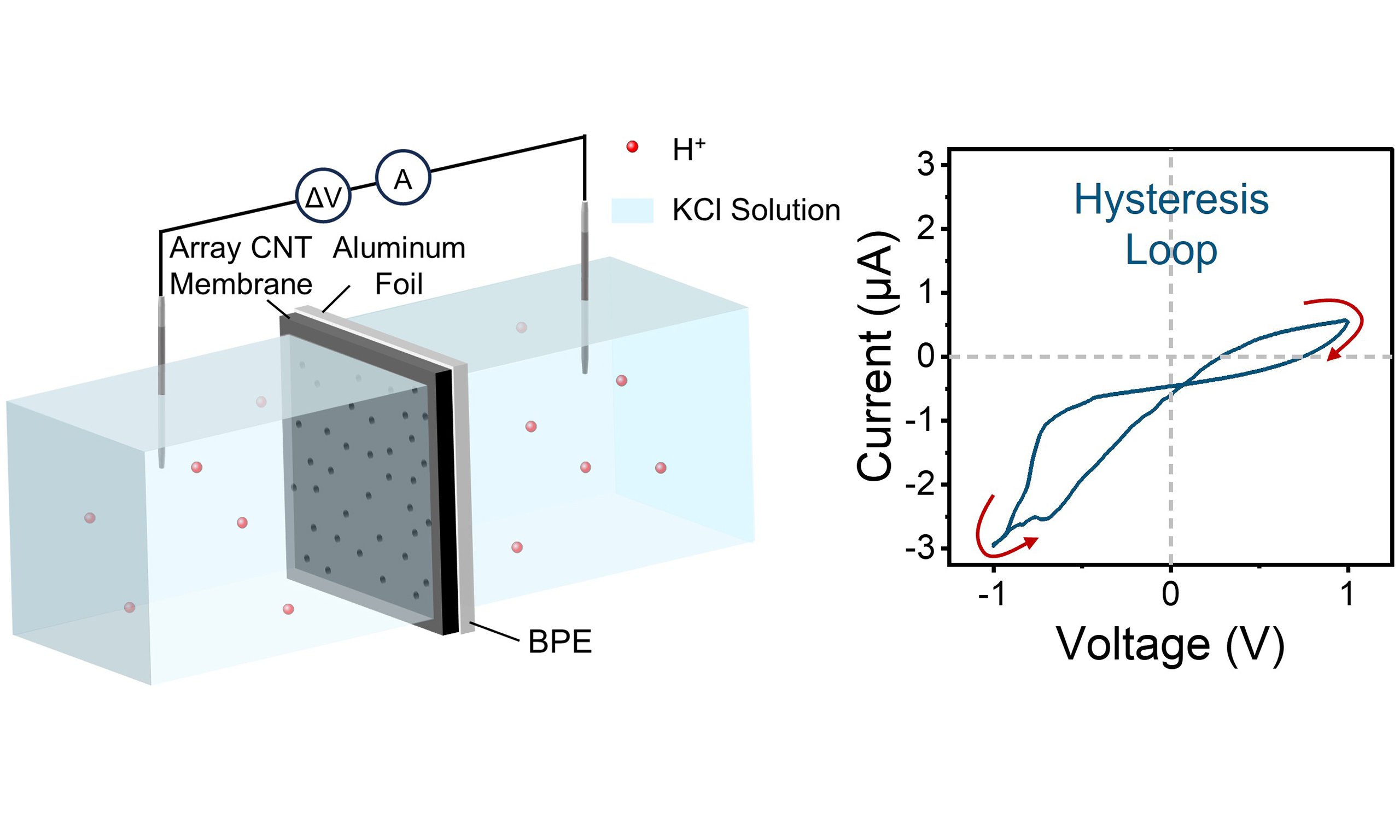

The ACNT membrane and Al foil are contacted tightly and mounted into a two-compartment cell as a separator to test current [Figure 1A], and the photo of the experimental setup is shown in Supplementary Figure 2. The current path in the device is composed of aqueous ion diffusion, ion-electron exchange through interfacial electrochemical reactions and electronic conduction through the Al BPE. Here, the ACNT membrane is a hybrid material consisting of carbon nanotube (CNT) channels embedded in EP[29]. The EDS of the ACNT membrane demonstrates the uniform distribution of nitrogen from the polymer [Supplementary Figure 3]. The Al foil used is high-purity and polished custom foil [Supplementary Figure 4]. Additionally, SEM images reveal numerous CNT openings exposed on the outer surface of continuous EP [Supplementary Figure 5A]. The SEM images show nearly identical microtopography on both sides of the Al foil, despite slight differences in gloss resulting from the manufacturing process [Supplementary Figure 5B and C]. Both the ACNT membrane and Al foil exhibit negative zeta potentials [Supplementary Figure 6]. The ACNT membrane is initially hydrophobic, but the plasma treatment opens the ports of CNTs and grafts them with carboxyl groups, thereby turning the hydrophobic surface into hydrophilic [Supplementary Figure 7A and B][30]. Meanwhile, although the Al foil shows only weak hydrophilicity, it is sufficiently wettable by the solution to ensure effective interfacial contact [Supplementary Figure 7C]. When the Al foil and the ACNT membrane were tested separately, both exhibited symmetrical current responses. However, when the two were simply combined as described above, an asymmetric interface was formed, and memristive characteristics of hysteresis and rectification were observed [Figure 1B].

Figure 1. The ACNT/Al BPE iontronic memristor. (A) Schematic diagram of the installation and experimental setup of ACNT/Al, showing the internal current path; (B) (i) Simplified schematic diagrams of the Al, ACNT, and ACNT/Al systems and (ii) the corresponding I-V responses under a triangular potential waveform at an electrolyte concentration of 10 mM and a scan rate of 0.3 V/s. Both the electrochemical Al system and the nanofluidic ACNT system show symmetric, non-memristive I-V characteristics, whereas the asymmetric ACNT/Al BPE with coupling between electrochemical and nanofluidic processes exhibits a characteristic hysteresis loop typical of iontronic memristors. ACNT/Al: Al and CNT array-based aluminum; ACNT: a carbon nanotube array; Al: aluminum; CNT: carbon nanotube; BPE: bipolar electrode; I-V: current-voltage.

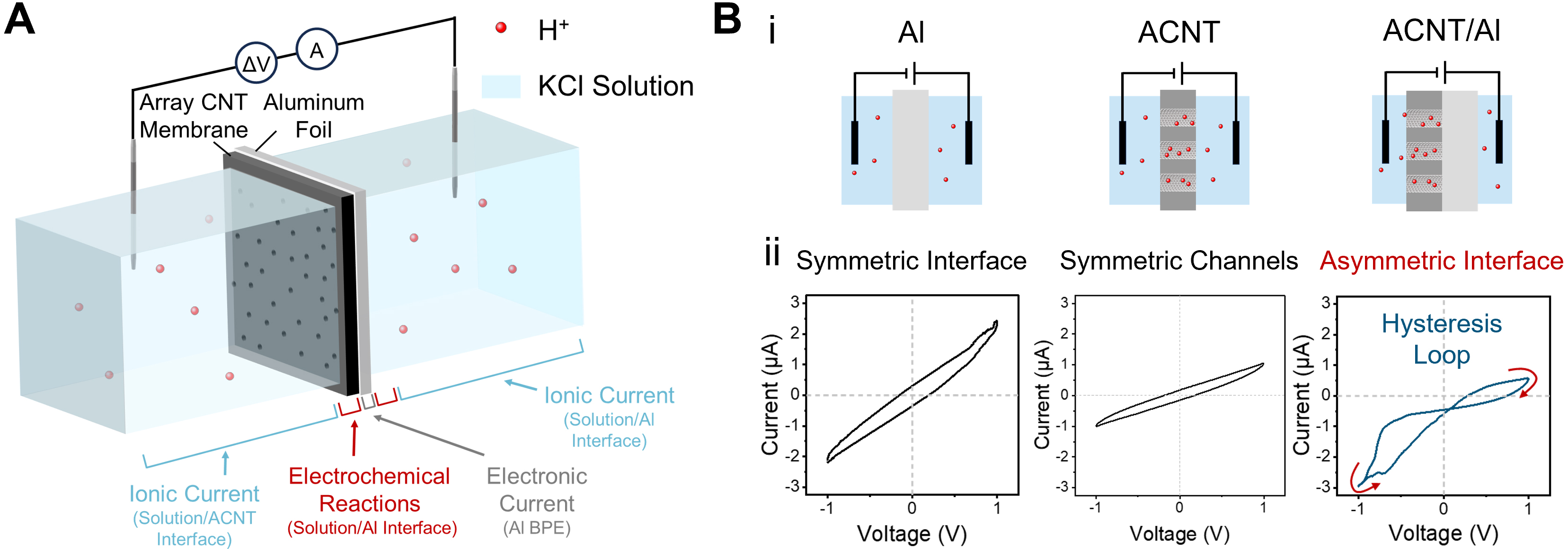

In the Al and CNT array-based aluminum (ACNT/Al) system, the potential difference at the Al-solution interface drives redox reactions[31]. The end with higher potential serves as the anode, where the oxidation reaction occurs: Al → Al3+ + 3e-, followed by Al3+ + 3H2O → Al(OH)3 +3H+. The end with lower potential serves as the cathode, where the reduction reaction occurs: 2H+ → H2 + 2e-. The critical potentials required to trigger these half-reactions are Eox,1 and Ered,1 (Eox,2 and Ered,2 for the opposite potential), defined by thermodynamic equilibrium potentials and overpotentials[32]. Although Al naturally forms an oxide film upon contact with aqueous solutions, the presence of Cl- induces pitting corrosion, exposing and dissolving the Al surface, allowing the reactions to proceed[33]. This is further confirmed by the SEM comparison of the Al foil before and after testing, which shows the formation of small corrosion sites on the aluminum surface induced by Cl- after testing [Supplementary Figure 8]. Consequently, the net driving potentials remain symmetrical under opposite potentials (ΔE1 = ΔE2), due to the identical surface conditions of both poles of Al [Figure 2A]. Notably, under the moderate operating conditions employed in this work (applied potential ≤ 1.5 V and a KCl concentration of 10 mM), the dissolution of Al is limited and does not lead to significant consumption. Repeated measurements under identical conditions demonstrate preserved memristive characteristics with minor variations, confirming the operational stability of the device [Supplementary Figure 9]. The ACNT membrane also features symmetric geometry and interfacial physicochemical properties. As a result, ion migration within its nanochannels proceeds equivalently under forward and reverse biases, generating equal ionic currents under opposite potentials [Figure 2B].

Figure 2. Mechanism of the BPE iontronic memristor. (A) Schematic diagram of ion behavior and potential illustration under opposite bias in Al system; (B) Schematic diagram of ion behavior under opposite bias in ACNT system; (C) Schematic diagram of ion behavior and potential illustration under opposite bias in ACNT/Al system. Eox,1 and Ered,1 respectively represent the critical potentials of half-reactions at the anodic pole and cathodic pole in Al. E’ox,1 and E’red,1 respectively represent the critical potentials of half-reactions at the anodic pole and cathodic pole in ACNT/Al. ΔE1 and ΔE’1 represent the net driving potential in Al and ACNT/Al, respectively. The parameters with the subscript “2” correspond to the respective values under the reversed bias. BPE: Bipolar electrode; Al: aluminum; ACNT: a carbon nanotube array; ACNT/Al: Al and CNT array-based aluminum; CNT: carbon nanotube.

In contrast, the ACNT/Al BPE system exhibits rectification and memristive behaviors arising from the asymmetry in reaction conditions [Figure 2C]. Owing to the negative charges of the CNTs, the ACNT membrane preferentially transports and enriches cations, leading to H+ accumulation inside the CNT channels. Consequently, this selective H+ accumulation breaks the initial symmetry of H+ concentration on the two sides of the Al foil, creating a higher local H+ concentration at the ACNT/Al interface compared with the Al/solution interface. When the ACNT membrane is placed at the cathode of Al, H+ ions serve as the reactants in the cathodic reaction, reducing the overpotential (E’red,1 < Ered,1), while Cl- continues to damage the oxide film at the anode. This decreases the overall voltage required for the redox reactions, increasing the net driving potential (ΔE’1 > ΔE1) and leading to faster reaction rate (v’1 > v1). Therefore, the reaction current increases gradually under negative bias. Conversely, when the ACNT membrane is placed at the anode, and H+ ions are the products in the anodic reaction, the higher H+ concentration in the channels inhibits the anodic reaction. This leads to a higher overpotential (E’ox,2 > Eox,2) and a lower net driving potential and reaction rate (ΔE’2 < ΔE2, v’2 < v2). Therefore, the reaction current decreases gradually under positive bias. Together, these asymmetric reaction kinetics give rise to the observed diode-like rectification characteristics of ACNT/Al. Due to the slow kinetics of H+ accumulation and depletion, as well as oxide film dissolution and formation - which occur more slowly than the voltage sweep - the coupling of ion transport and interfacial reaction kinetics produces a lag between voltage and current, consistent with the hysteretic characteristics of the I-V curve for the ACNT/Al system. Importantly, this mechanism is not limited to specific material combinations but originates from the general interplay between electrostatically induced ion rearrangement and reaction kinetics, providing a versatile basis for ionic signal processing in neuromorphic computing in aqueous environments.

Tuning ion transport in ACNT nanochannels

The ACNT membrane tunes one side of the ion transport in the electrochemical reactions resulting in memristive behavior. To verify the existence of electrochemical reactions, four metals with different reactivities were tested individually and combined with the ACNT membrane, which are silver (Ag), copper (Cu), zinc (Zn) and Al, and their I-V behaviors are obtained via a triangular voltage waveform. The I-V curves are symmetric under opposite potentials since both sides of the four metals are identical [Supplementary Figure 10]. When mounted with ACNT membrane, a slight rectification was observed due to the overall asymmetry of the system. The two systems with inert metals, ACNT/Ag and ACNT/Cu, exhibited no memristive behaviors. In contrast, the two with active metals, ACNT/Zn and ACNT/Al, exhibited a hysteresis in the rectified I-V curves [Supplementary Figure 11]. The currents for Ag and Cu correspond to the normal capacitance charging current, which arises from the EDL of their exterior surfaces[34]. It is indicated that ion migration or accumulation within the CNT channels alone is insufficient to generate significant hysteresis. Pronounced memristive behavior emerges only when ion transport is coupled with electrochemical reactions at the BPE poles, allowing the slow kinetics of both processes and substantial asymmetry in reaction conditions.

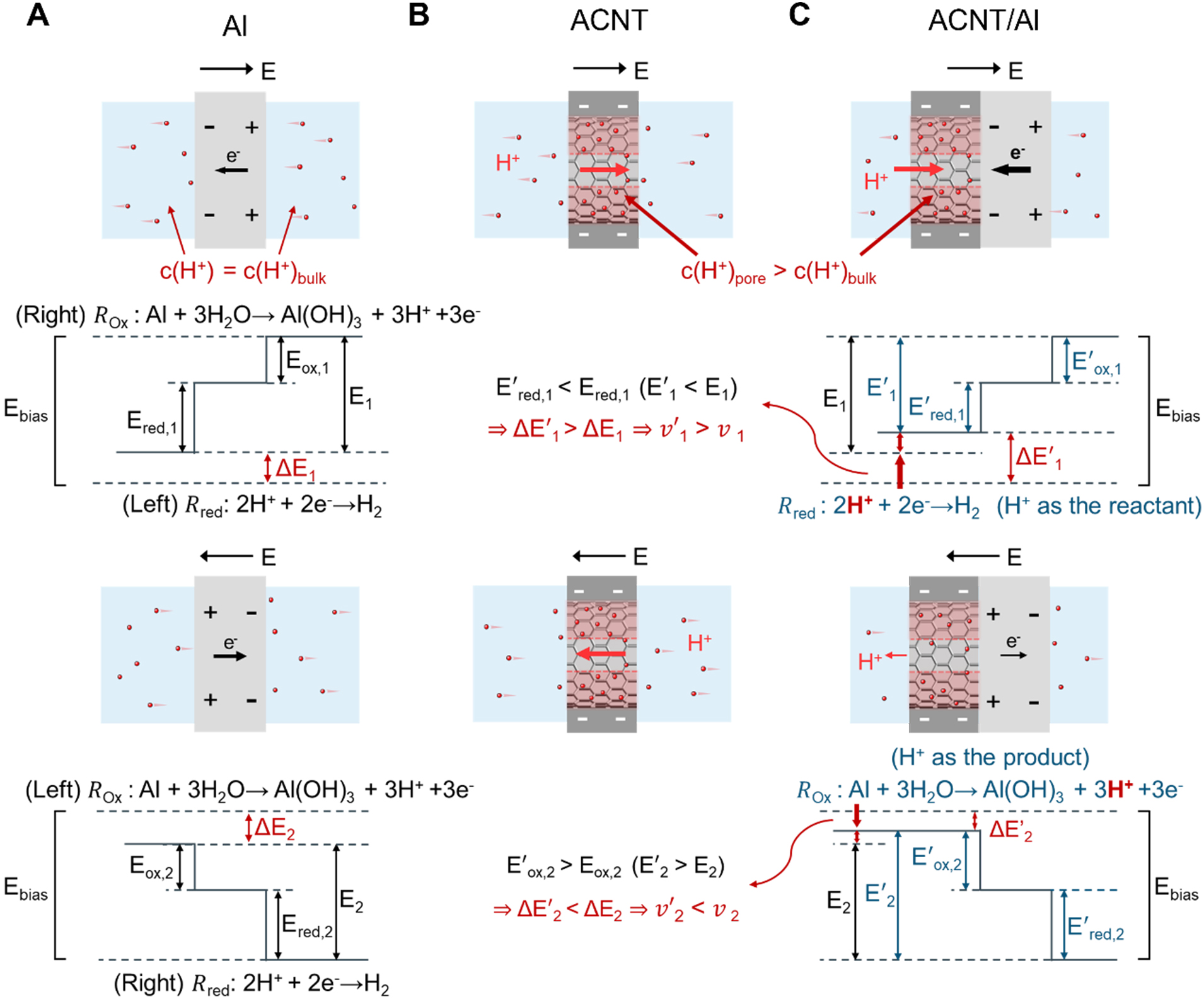

To examine whether the asymmetric structure of ACNT/Al introduces distinct reaction conditions, as evidenced by the pronounced memristive and rectifying behavior observed in the asymmetric configuration [Figure 3A, i], we constructed a three-layer symmetrical structure of ACNT/Al/ACNT [Figure 3A, ii]. In this system, H+ migration on both sides of the Al foil is regulated by the ACNT membranes, resulting in symmetric electrochemical kinetics at the two poles. The absence of memristive effects showed that the kinetic difference in the electrochemical reactions is the key to the hysteretic mechanism. To further verify the influence of the asymmetric interfaces, the I-V behavior of the asymmetric four-layer structure (ACNT/Al/ACNT/Al) was obtained [Figure 3A, iii], which demonstrated the memristive characteristic. This proves that the memristive mechanism stems from the asymmetric ion migration and electrochemical reactions that occur at the ACNT/Al interface and the Al/solution interface.

Figure 3. Ion transport regulation of the ACNT membrane. (A) I-V curves obtained from different configurations (symmetric and asymmetric): (i)ACNT/Al, (ii) ACNT/Al/ACNT and (iii) ACNT/Al/ACNT/Al, demonstrating a hysteretic loop behavior only in asymmetric configurations; (B) Comparative I-V responses of CNT membranes without oriented channels: (i) CNT and (iii) CNT/Al; and ACNT membranes with oriented channels: (ii) ACNT and (iv) ACNT/Al; (C) Schematic of the ACNT/Al system under applied stress; (D) I-V curves of ACNT/Al under various applied pressures. All I-V measurements were performed in 10 mM KCl at a scan rate of 0.3 V/s. ACNT: A carbon nanotube array; I-V: current-voltage; ACNT/Al: Al and CNT array-based aluminum; CNT: carbon nanotube.

To verify the role of ion-selective transfer in nanochannels, CNT membranes without oriented CNT channels were prepared by grinding the CNT array before it was mixed with EP. As a result, ions cannot migrate through the interior of CNT channels. The CNT membrane also exhibited a measurable current [Figure 3B, i], due to the presence of a few residual channels that cannot be completely excluded. However, its current is two orders of magnitude lower than that of ACNT [Figure 3B, ii]. When the CNT membrane is combined with Al (CNT/Al), the overall current increases compared with CNT alone, yet no memristive behavior is observed [Figure 3B, iii]. This confirms that both nanoscale confinement and ion selectivity within the CNT channels are essential for ion accumulation and depletion, leading to significant differences in reaction kinetics. Additionally, this conclusion can also be supported by [Figure 3B, iv], as the selective ion transport at negative potential greatly increases the cathodic reaction current.

The CNTs have excellent deformation properties and can sustain deformation within the elastic range under the external stress[35]. Meanwhile, the introduction of EP as an embedding medium maintains the recoverable deformability of the membrane. The I-V behaviors were obtained when it was under dynamic stress regulation [Figure 3C]. The bending of the ACNT structure under applied pressure increases the resistance to ion transport within the CNT channels. Under no stress, the cross-sections of CNTs are generally circular, exerting nearly no inhibition to ion transport. When being compressed axially, local buckling or even collapse appears[36], thereby hindering the passage of cations [Supplementary Figure 12]. Consequently, in the ACNT/Al BPE system, increased stress causes elastic bending of the CNTs, which impedes the interior ion transport. As the applied stress rises, the hysteretic current gradually decreases [Figure 3D]. This phenomenon further proves that the asymmetric H+ migration across the two sides of Al is a key factor of the memristive behavior in the ACNT/Al BPE system. Furthermore, the combination of mechanical flexibility, stress-responsive ion transport, and aqueous operation offers the ACNT membrane with strong potential for applications in bio-interfaced iontronics, where soft mechanics and biocompatibility are essential.

The memristive behaviors under different conditions

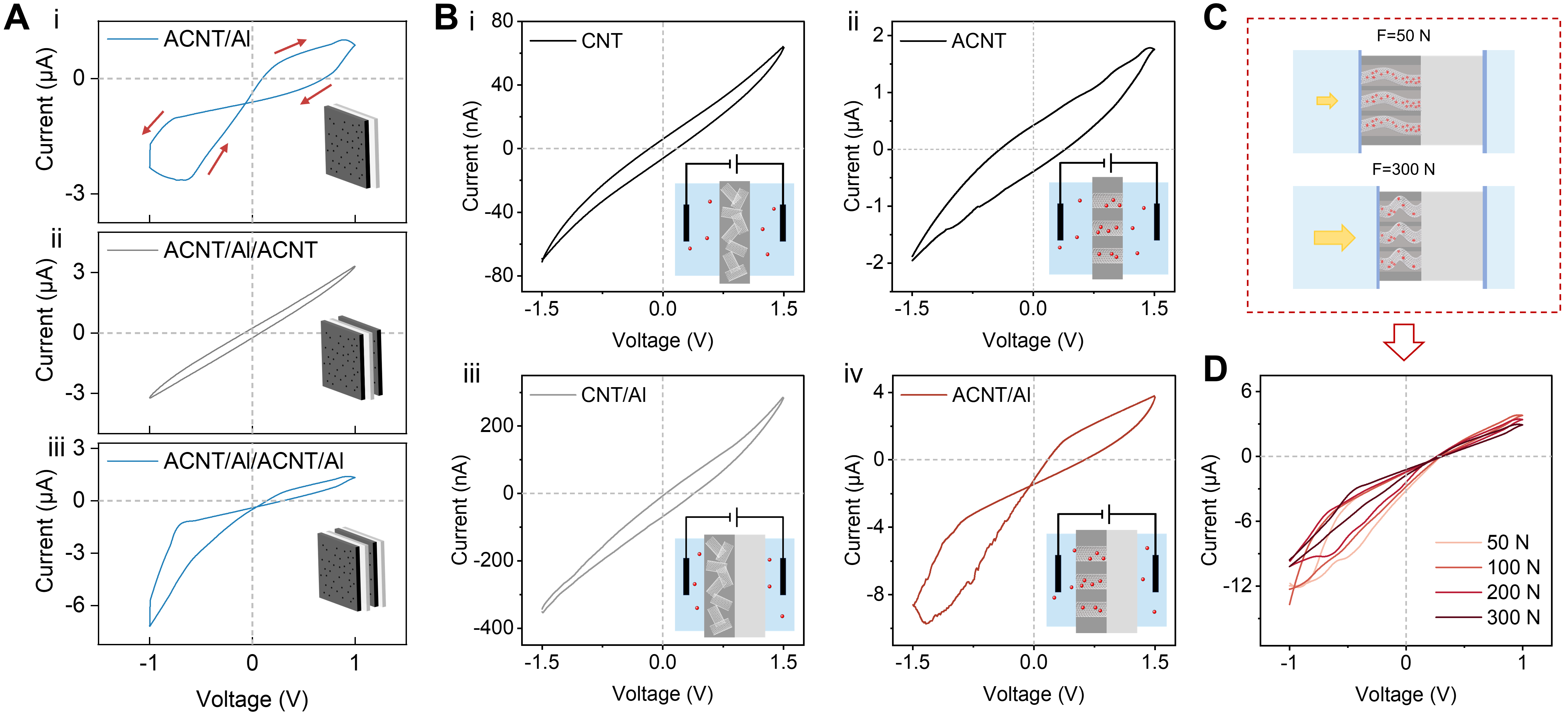

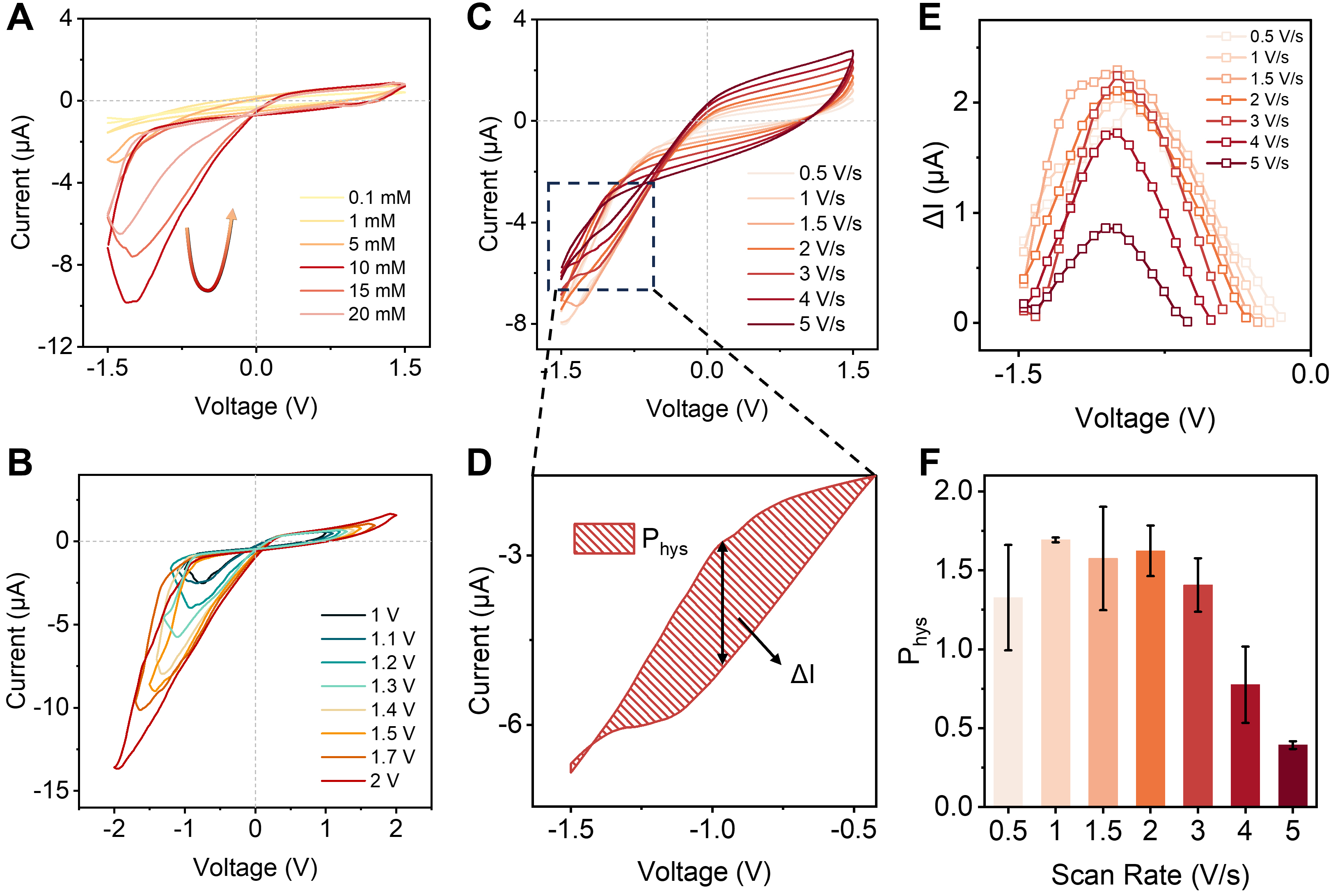

To study the influence of parameters on the memristor behavior, I-V tests were conducted at different electrolyte concentrations. The curves show only symmetrical capacitance charging currents in KCl solutions at concentrations of 1 and 0.1 mM [Figure 4A], likely due to the low Cl- concentration greatly weakening the corrosive effect on Al, thereby preventing the electrochemical reactions. Correspondingly, as the KCl concentration increases from 1 to 10 mM, the current increases significantly and memristive behavior emerges at the concentration of 5 mM, indicating the activation of electrochemical reactions. At higher electrolyte concentrations, however, the memristive characteristics do not further improve due to enhanced electrostatic screening, which weakens ion selectivity and suppresses H+ accumulation within the CNT nanochannels. Therefore, 10 mM KCl is identified as an optimal electrolyte concentration for achieving pronounced and stable memristive behavior. A similar trend was observed at a voltage range of ±1.0 V [Supplementary Figure 13]. In the 10 mM KCl solution, the memristor behavior within different scanning voltage ranges was regulated [Figure 4B]. The system showed no hysteresis below a voltage of ±1 V [Supplementary Figure 14], due to the slow speed of ion migration and rearrangement, and because the applied voltage was lower than the critical voltage required to trigger the reaction. When the applied voltage exceeded ±1.0 V, the memristive characteristics are enhanced and well preserved as the scan voltage range is increased from ±1.0 to ±2.0 V. However, higher voltages also accelerate electrochemical corrosion of the Al BPE. Considering the long-term stability of the system, the operating voltage in this work was therefore limited to ±1.5 V.

Figure 4. Memristive performance of the ACNT/Al system. (A) I-V curves obtained at different electrolyte concentrations (0.3 V/s), showing the most pronounced hysteretic behavior at 10 mM KCl; (B) I-V curves measured within various voltage ranges (10 mM KCl,

The memristive behavior maintains over a wide range of scan rate from the I-V curves[37] [Figure 4C]. The area below the cross-point corresponds to the excitatory state of ion accumulation, characterized by a continuous increase in effective conductance. The area above the cross-point corresponds to the inhibitory state of ion depletion, characterized by a continuous decrease in effective conductance. The current difference (ΔI) of the excitatory state was obtained by subtracting the forward curve from the reverse curve as shown in Figure 4D, which is analogous to the on-off ratio in the memristor [Figure 4E]. In the excitatory state, the reaction current exceeded the capacitance charging current and increased progressively with scan rate, leading to the hysteresis characteristic, with the highest on-off ratio at 1.5 V/s of scan rate. Meanwhile, the current at the inhibitory state manifested mainly as the capacitance charging current, on account of the weak reaction current and rapid charging current at higher scan rates. Also, the corresponding loop areas (Phys) for the excitatory state were obtained by integrating the loop areas below the cross-point. At low scan rates, there is sufficient time for ions to approach their quasi-equilibrium concentrations, inhibiting further growth in current amplitude and producing a relatively modest hysteresis. At sufficiently high potentials, the ion distribution is unable to reach the non-equilibrium state of accumulation or depletion, and with the rapidly increasing capacitance charging current, the hysteretic current is completely overshadowed. Consequently, with increasing scan rate, the Phys of the excitatory state first increases and then declines [Figure 4F]. Additionally, as the scan rate increases, the capacitive current continues to grow in proportion until it dominates the total current, so the cross-point shifted to more negative and ultimately disappeared.

The simulation of short-term synaptic plasticity

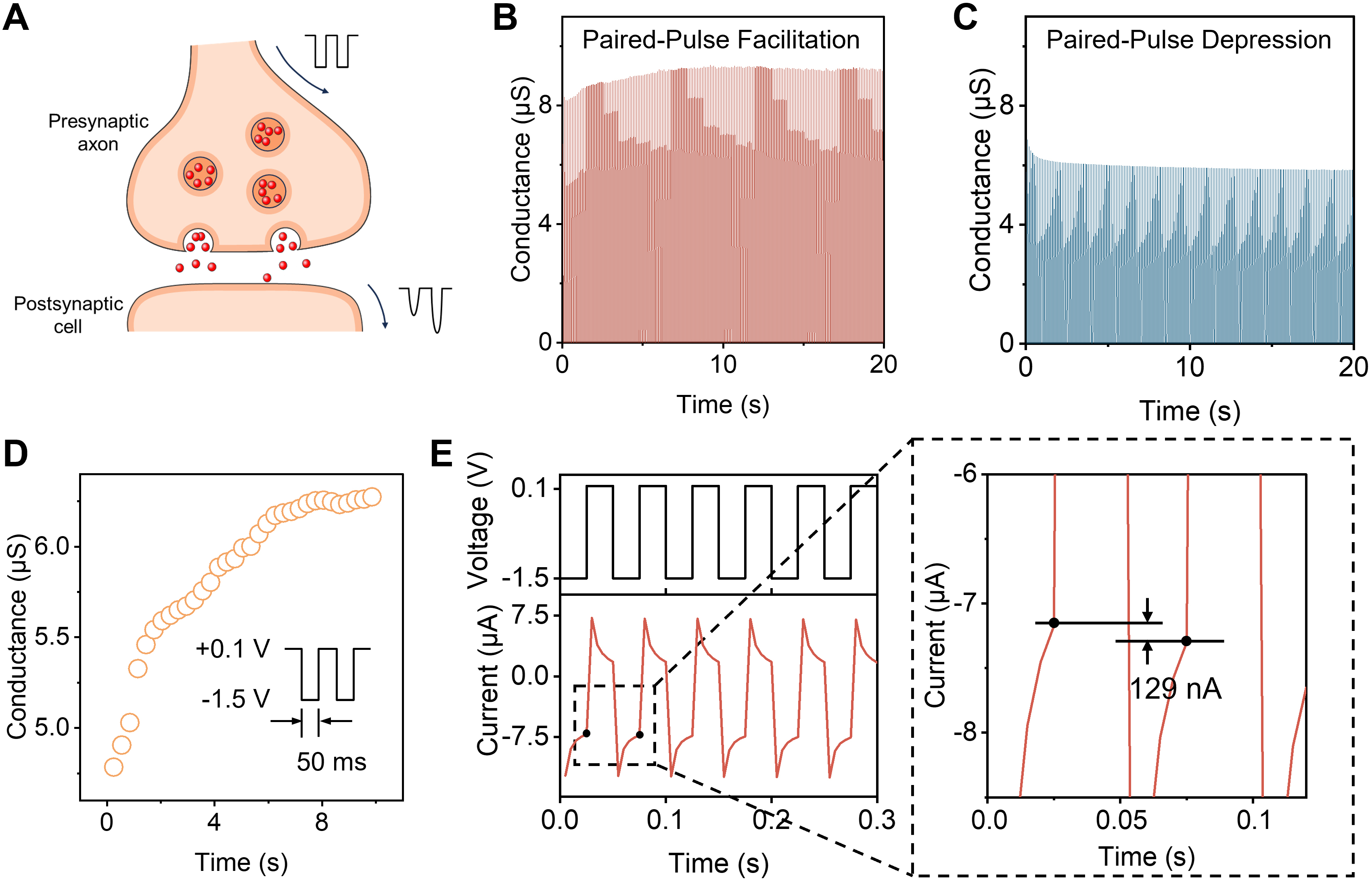

To emulate synaptic plasticity in short-term memory, paired-pulse facilitation (PPF) and paired-pulse depression (PPD) are characterized as important forms of memory and learning[38,39] [Figure 5A]. The second pulse produces either an enhanced or suppressed response relative to the first pulse under consecutive stimulations. This behavior arises from the polarization or depolarization of internal ions, corresponding to PPF and PPD, respectively[40-45]. A series of presynaptic pulses with -1.5 V amplitude, 50 ms duration, and 50 ms interval (with an interval voltage of 0.1 V) were applied, yielding an enhancement in the ionic conduction that mimics the PPF behavior [Figure 5B]. Under identical successive pulses with an opposite voltage amplitude (+1.5 V), the emulation of PPD is observed [Figure 5C]. The conductance values of the pulses during the initial 10 s were extracted and plotted, revealing an initial rise followed by gradual saturation [Figure 5D]. Upon -1.5 V pulse stimulation, abundant cations are instantaneously driven into the cation-selective CNT channels. However, a single pulse is insufficient to reach ion saturation, and during the relaxation interval with a positive bias, part of the cations flows out of the CNT channels. If the subsequent pulse stimulation arrives before the cations are completely depleted, the conductance of the next pulse increases due to the residual ionic state from the previous pulse. The electrochemical reaction current consequently increases stepwise, analogous to the weight modulation in biological synapses[46,47].

Figure 5. Synaptic emulation behavior of the ACNT/Al system. (A) Schematic illustration of signal transmission in biological synapses; (B) The increased conductance under successive negative pulses (-1.5 V), emulating the PPF property; (C) The decreased conductance under successive positive pulses (+1.5 V), emulating the PPD property; (D) The extracted conductance evolution within the initial 10 s from (B), showing the gradual increase of tendency; (E) The current response curves of ACNT/Al and the current difference between the first two pulses. ACNT/Al: Al and CNT array-based aluminum; Al: aluminum; CNT: carbon nanotube; PPF: paired-pulse facilitation; PPD: paired-pulse depression.

Owing to the intrinsic conductivity of the system, a rapid charging current was generated at the onset of pulse stimulation, producing a sharp current peak followed by a gradual decay [Figure 5E]. To eliminate the transient capacitive effect, the current value at the end of the pulse was taken as the synaptic current. Furthermore, the current of the second pulse increased by 129 nA compared with the first pulse, demonstrating that the ACNT/Al system can effectively emulate excitatory synaptic behavior and its subsequent function in bioinspired memristors. The observation of short-term synaptic plasticity demonstrates that the ACNT/Al system can emulate fundamental neuromorphic functions, such as short-term memory, spike-timing-dependent integration, and synaptic strength modulation, thereby highlighting its applicability for brain-inspired computing based on ionic signal modulation.

CONCLUSIONS

In summary, we have demonstrated an iontronic memristor based on an ACNT/Al BPE. By exploiting the opposing effects of paired redox reactions influenced by the same ions, the ACNT membrane induces selective ion accumulation on one side of the BPE, resulting in voltage-dependent promotion or inhibition of the reaction current with hysteresis. This asymmetric electrochemical environment enables both rectifying and hysteretic characteristics of the memristor and allows the emulation of short-term excitatory synaptic behaviors. Moreover, the ACNT/Al system goes beyond conventional nanofluidic memristors, which rely solely on limiting ion transport to induce hysteresis. By coupling ion-selective nanochannels with the intrinsic kinetics of electrochemical reactions, it achieves memristive behavior while maintaining fast ion migration. This strategy provides a new approach for developing iontronic memristors in aqueous solutions and offers the potential to design high-performance devices by incorporating various electrochemical materials and redox reactions.

DECLARATIONS

Authors’ contributions

Led the project: Hou, X.

Conceived the idea: Hou, X.; Hou, Y.

Made substantial contributions to conception and design of the study and performed data analysis and interpretation: Zhou, L.; Luo, C.

Carried out the supplementary experiments: Luo, C.; Xu, R.

Performed draft revision and provided administrative, technical, and material support: Hou, Y.; Hou, X.

Contributed to the discussions of the manuscript: Luo, C.; Zhou, L.; Xu, R.; Hou, Y.; Hou, X.

Luo, C. and Zhou, L. contributed equally to the article.

Availability of data and materials

Additional information is available in the Supplementary Materials.

Financial support and sponsorship

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Beijing, China; Nos. 52025132, 52303380, U24A20205, 21621091, 22021001, 22121001), the 111 Project (Nos. B17027 and B16029, China), the National Natural Science Foundation of Fujian Province, China (No. 2022J02059), and the New Cornerstone Science Foundation through the XPLORER PRIZE (China).

Conflicts of interest

Hou, X. is an Associate Editor of the journal Iontronics. Hou, X. was not involved in any steps of the editorial process, notably including reviewers’ selection, manuscript handling, or decision-making. The other authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026.

Supplementary Materials

REFERENCES

3. Xu, G.; Zhang, M.; Mei, T.; Liu, W.; Wang, L.; Xiao, K. Nanofluidic ionic memristors. ACS. Nano. 2024, 18, 19423-42.

4. Song, R.; Wang, P.; Zeng, H.; et al. Nanofluidic memristive transition and synaptic emulation in atomically thin pores. Nano. Lett. 2025, 25, 5646-55.

5. Xiong, T.; Li, W.; Yu, P.; Mao, L. Fluidic memristor: bringing chemistry to neuromorphic devices. Innovation 2023, 4, 100435.

6. Shi, D.; Wang, W.; Liang, Y.; Duan, L.; Du, G.; Xie, Y. Ultralow energy consumption angstrom-fluidic memristor. Nano. Lett. 2023, 23, 11662-8.

7. Ramirez, P.; Portillo, S.; Cervera, J.; Bisquert, J.; Mafe, S. Memristive arrangements of nanofluidic pores. Phys. Rev. E. 2024, 109, 044803.

8. Kamsma, T. M.; Boon, W. Q.; Ter Rele, T.; Spitoni, C.; van Roij, R. Iontronic neuromorphic signaling with conical microfluidic memristors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2023, 130, 268401.

9. Baram, D.; Kvetny, M.; Ake, S.; Yang, R.; Wang, G. Anodized aluminum oxide membrane ionic memristors. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2025, 147, 11089-97.

10. Wang, D.; Kvetny, M.; Liu, J.; Brown, W.; Li, Y.; Wang, G. Transmembrane potential across single conical nanopores and resulting memristive and memcapacitive ion transport. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 3651-4.

11. Hu, X.; Xu, H.; Lu, J.; et al. Selective ion transport of nonlinear resistive switching by hierarchical nanometer-to-angstrom channels for nanofluidic transistors. Sci. Adv. 2025, 11, eadw7882.

12. Emmerich, T.; Teng, Y.; Ronceray, N.; et al. Nanofluidic logic with mechano-ionic memristive switches. Nat. Electron. 2024, 7, 271-8.

13. Zhou, X.; Zong, Y.; Wang, Y.; et al. Nanofluidic memristor based on the elastic deformation of nanopores with nanoparticle adsorption. Natl. Sci. Rev. 2024, 11, nwad216.

14. Niu, Y.; Ma, Y.; Xie, Y. Soft memristor at a microbubble interface. Nano. Lett. 2024, 24, 10475-81.

15. Robin, P.; Kavokine, N.; Bocquet, L. Modeling of emergent memory and voltage spiking in ionic transport through angstrom-scale slits. Science 2021, 373, 687-91.

16. Robin, P.; Emmerich, T.; Ismail, A.; et al. Long-term memory and synapse-like dynamics in two-dimensional nanofluidic channels. Science 2023, 379, 161-7.

17. Ismail, A.; Nam, G. H.; Lokhandwala, A.; et al. Programmable memristors with two-dimensional nanofluidic channels. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 7008.

18. Xiong, T.; Li, C.; He, X.; et al. Neuromorphic functions with a polyelectrolyte-confined fluidic memristor. Science 2023, 379, 156-61.

19. Yang, R.; Balogun, Y.; Ake, S.; Baram, D.; Brown, W.; Wang, G. Negative differential resistance in conical nanopore iontronic memristors. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2024, 146, 13183-90.

20. Zhang, Z.; Sabbagh, B.; Chen, Y.; Yossifon, G. Geometrically scalable iontronic memristors: employing bipolar polyelectrolyte gels for neuromorphic systems. ACS. Nano. 2024, 18, 15025-34.

21. Che, Q.; Li, C.; Chen, Z.; Yang, S.; Zhang, W.; Yu, G. High performance memristors based on imine-linked covalent organic frameworks obtained using a protonation modification strategy. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2024, 63, e202409926.

22. Wang, W.; Liang, Y.; Ma, Y.; Shi, D.; Xie, Y. Memristive characteristics in an asymmetrically charged nanochannel. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2024, 15, 6852-8.

23. Xiao, Y.; Sun, W.; Gao, C.; et al. Neural functions enabled by a polarity-switchable nanofluidic memristor. Nano. Lett. 2024, 24, 12515-21.

24. Wang, Y. L.; Cao, J. T.; Liu, Y. M. Bipolar electrochemistry - a powerful tool for micro/nano-electrochemistry. ChemistryOpen 2022, 11, e202200163.

25. Fosdick, S. E.; Knust, K. N.; Scida, K.; Crooks, R. M. Bipolar electrochemistry. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2013, 52, 10438-56.

26. Seeber, R.; Zanardi, C.; Inzelt, G. The inherent coupling of charge transfer and mass transport processes: the curious electrochemical reversibility. ChemTexts 2016, 2, 8.

27. Kwan, K. W.; Ngan, A. H. W. A tuneable ionic memristor based on bipolar electrochemistry. J. Mater. Chem. C. 2025, 13, 17537-43.

28. Yu, L.; Hou, Y.; Wang, Y.; et al. Quartz nonadherent and clean exfoliation of the heteroatom-doped bulk carbon nanotubes array. Nano. Lett. 2023, 23, 9383-91.

29. Yang, D.; Tian, D.; Xue, C.; et al. Tuned fabrication of the aligned and opened CNT membrane with exceptionally high permeability and selectivity for bioalcohol recovery. Nano. Lett. 2018, 18, 6150-6.

30. Hosseini, H.; Ghaffarzadeh, M. Surface functionalization of carbon nanotubes via plasma discharge: a review. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2022, 138, 109276.

31. Mechelhoff, M.; Kelsall, G. H.; Graham, N. J. Electrochemical behaviour of aluminium in electrocoagulation processes. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2013, 95, 301-12.

32. Seidenberg, J. R.; Mitsos, A.; Bongartz, D. Interpreting concentration and activation overpotentials in electrochemical systems: a critical discussion. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2025, 172, 043506.

33. Natishan, P. M.; O’grady, W. E. Chloride ion interactions with oxide-covered aluminum leading to pitting corrosion: a review. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2014, 161, C421-32.

34. Liu, Y.; Chandresh, A.; Heinke, L. Impact of the channel length in nanoporous electric double-layer capacitors on the charge transport explored by metal-organic framework films. ACS. Phys. Chem. Au. 2025, 5, 266-73.

35. Falvo, M. R.; Clary, G. J. Taylor RM, 2. N. D.; et al. Bending and buckling of carbon nanotubes under large strain. Nature 1997, 389, 582-4.

36. Wang, C.; Liu, Y.; Al-ghalith, J.; Dumitrică, T.; Wadee, M.; Tan, H. Buckling behavior of carbon nanotubes under bending: from ripple to kink. Carbon 2016, 102, 224-35.

37. Chen, K.; Tsutsui, M.; Zhuge, F.; et al. Nanochannel - based interfacial memristor: electrokinetic analysis of the frequency characteristics. Adv. Electron. Mater. 2021, 7, 2000848.

38. Zucker, R. S.; Regehr, W. G. Short-term synaptic plasticity. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2002, 64, 355-405.

39. Blitz, D. M.; Foster, K. A.; Regehr, W. G. Short-term synaptic plasticity: a comparison of two synapses. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2004, 5, 630-40.

40. Kamsma, T. M.; Kim, J.; Kim, K.; et al. Brain-inspired computing with fluidic iontronic nanochannels. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2024, 121, e2320242121.

41. Xu, Y. T.; Yu, S. Y.; Li, Z.; et al. A nanofluidic spiking synapse. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2024, 121, e2403143121.

42. Ramirez-morales, R. R.; Ponce-ponce, V. H.; Molina-lozano, H.; Sossa-azuela, H.; Islas-garcía, O.; Rubio-espino, E. Analog implementation of a spiking neuron with memristive synapses for deep learning processing. Mathematics 2024, 12, 2025.

43. Li, P.; Liu, J.; Yuan, J. H.; et al. Artificial funnel nanochannel device emulates synaptic behavior. Nano. Lett. 2024, 24, 6192-200.

44. Ramirez, P.; Portillo, S.; Cervera, J.; et al. Neuromorphic responses of nanofluidic memristors in symmetric and asymmetric ionic solutions. J. Chem. Phys. 2024, 160.

45. Li, J.; Xu, H.; Sun, S.; et al. In situ learning in hardware compatible multilayer memristive spiking neural network. IEEE. Trans. Cogn. Dev. Syst. 2022, 14, 448-61.

46. Noh, Y.; Smolyanitsky, A. Synaptic-like plasticity in 2D nanofluidic memristor from competitive bicationic transport. Sci. Adv. 2024, 10, eadr1531.

Cite This Article

How to Cite

Download Citation

Export Citation File:

Type of Import

Tips on Downloading Citation

Citation Manager File Format

Type of Import

Direct Import: When the Direct Import option is selected (the default state), a dialogue box will give you the option to Save or Open the downloaded citation data. Choosing Open will either launch your citation manager or give you a choice of applications with which to use the metadata. The Save option saves the file locally for later use.

Indirect Import: When the Indirect Import option is selected, the metadata is displayed and may be copied and pasted as needed.

About This Article

Copyright

Data & Comments

Data

Comments

Comments must be written in English. Spam, offensive content, impersonation, and private information will not be permitted. If any comment is reported and identified as inappropriate content by OAE staff, the comment will be removed without notice. If you have any queries or need any help, please contact us at support@oaepublish.com.