Biological determinants and outcomes of sex discrepancies in MASLD

Abstract

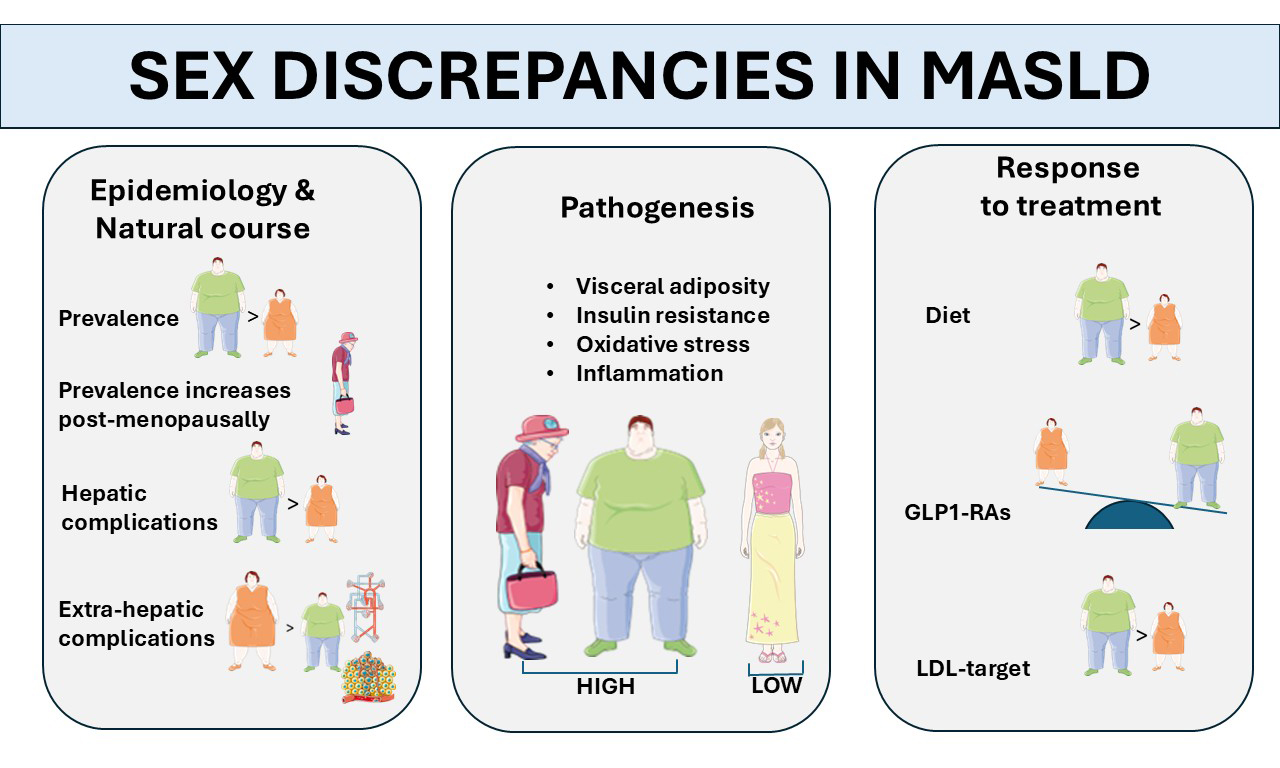

Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) defines the metabolic origin of ectopic accumulation of intrahepatic fatty substrates that affect multiple organ systems. Given the key role of sex in metabolic regulation, this article reviews sex-specific disparities in the epidemiology, pathomechanisms, clinical course, and therapeutic responses associated with MASLD. The influence of reproductive health on the risk of disease in males and females is also examined. Although MASLD is more prevalent in males, the protective effect observed in females diminishes following menopause, highlighting the significant roles that biological sex and reproductive status play in disease progression. Women may face an elevated risk of certain MASLD-related extra-hepatic complications, and ongoing research is elucidating the mechanisms underlying these sex disparities. Biological sex modifies MASLD susceptibility through diverse factors, including fat distribution, adipose tissue pathobiology, hormone signaling pathways, gene-hormone interactions, immune system dynamics, and bile acid composition. Menstrual and reproductive factors, as well as exogenous hormone exposure, further contribute to differential risk profiles. Both endogenous hormone concentrations and sex chromosome composition are relevant for liver health, as evidenced by increased susceptibility in conditions such as polycystic ovary syndrome and certain chromosomal aneuploidies. The review further discusses MASLD in the context of pregnancy and lactation and examines sex-based variation in response to lifestyle modification and pharmacological therapy. Finally, recommendations for future research directions are provided.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) is the latest term used in medical research and clinical practice to describe the spectrum of “nonalcoholic” fatty liver disorders with a metabolic cause[1]. The rationale underlying the MASLD definition emphasizes the “positive” diagnostic criterion, namely its association with metabolic dysfunction. The MASLD nomenclature has been endorsed by scientific societies due to its concise and clinically actionable diagnostic criteria, exclusion of other concomitant liver diseases, and lack of stigmatization[2]. MASLD is recognized to have a multisystemic impact throughout the entire life cycle, beginning in childhood[3]. Research indicates that pediatric MASLD exhibits a higher prevalence among males compared to females, even before puberty. This disparity is attributed to discrepancies in fat distribution, with boys demonstrating greater visceral adiposity, as well as distinct hormonal influences, such as the varying effects of testosterone and estrogen, and metabolic determinants, notably including insulin resistance. These contributing factors often intensify during adolescence, resulting in more pronounced liver biomarkers observed in male subjects[4].

During aging, sex-specific physiological changes, particularly reproductive hormones, alter susceptibility to MASLD and related complications[5]. Recognizing these patterns is essential for identifying at-risk groups and implementing targeted prevention and treatment strategies. Sex and gender play crucial roles in health, disease, and medicine[6], making male-to-female comparative studies essential in bio-medical research[7]. Accordingly, sex disparities are a key feature across chronic liver disease due to alcohol (ALD), viral hepatitis, MASLD, and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC)[8]. Studies indicated that women are typically exposed to higher risks than men of ALD while being relatively protected from certain types of viral hepatitis and HCC[8].

Research on MASLD began approximately 25 years ago. In 2000, Lonardo et al. discovered that a high body mass index (BMI) independently predicted steatotic liver disease (SLD) in both sexes, while dysfunctional glucose metabolism and central adiposity only predicted SLD in women, not in men[9]. Since then, numerous studies have been conducted, enhancing our understanding of the prevalence and causes of MASLD and metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MASH) in both sexes.

Given this background, our review differs from previously published articles in that it aims to:

(1) Analyze discrepancies between sexes in the epidemiology, clinical course, and potential treatment response rates of MASLD.

(2) Clarify the biological grounds underlying the observed sex variations.

(3) Explore how reproductive status and reproductive health influence MASLD risk in both women and men.

While sex is a biological variable, gender is a cultural construct based on different roles, responsibilities, attributes, and entitlements that exhibit intercultural disparities and are modifiable over time[10,11].

Lifestyle habits such as alcohol intake, dietary preferences, attitudes towards practicing sports and physical activity, willingness to submit to preventive medicine, and other factors vary according to gender and may impact the risks of developing liver fibrosis through epigenetic mechanisms[12,13]. However, these gender-related variables are beyond the scope of this review article, which specifically discusses sex as a biological variable in the MASLD field.

METHODS OF BIBLIOGRAPHIC RESEARCH

To capture the breadth of evidence on sex-related discrepancies in MASLD, we conducted a systematic literature search of PubMed/MEDLINE, Embase, Scopus, and Web of Science for studies published between January 1995 and August 2025. Our search strings included controlled vocabulary (e.g., MeSH/Emtree) and free-text terms for “metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease”, “nonalcoholic fatty liver disease”, “sex”, “sex hormones”, “sex chromosomes”, “reproductive factors”, “polycystic ovary syndrome”, “Turner syndrome”, and “Klinefelter syndrome”. Only English-language articles were ultimately included in the final analysis. Reference lists of pertinent reviews and primary papers, as well as recent conference abstracts from major hepatology and endocrinology meetings, were hand-searched to identify additional studies. Eligible publications comprised observational studies, randomized or non-randomized interventional trials, systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and key mechanistic animal or in-vitro investigations that addressed sex-specific aspects of MASLD epidemiology, pathogenesis, clinical outcomes, or treatment responses.

EPIDEMIOLOGY AND COURSE OF DISEASE

Analysis of the global disease burden from 2020 to 2021 has demonstrated that MASLD represents a major public health concern worldwide, with the highest rates found in Kuwait, Egypt, and Qatar. Enhancing awareness of risk factors and preventive strategies is essential across all nations, particularly in China, Sudan, and India, where both incidence and prevalence are rising sharply[14]. Different regional rates of incidence and prevalence of MASLD may be influenced by multiple factors, including variable hormonal plasma levels, menopausal status, patterns of body fat distribution, and coexisting metabolic traits. The study specifically identified that the prevalence of MASLD peaks at different ages based on sex: men reached their highest prevalence in the 45-49 age group, while women exhibited a peak in the 50-54 age group. These findings indicate distinct physiological changes in metabolic function and hepatic lipid accumulation between men and women[14].

Sex and MASLD onset and progression

The prevalence of MASLD is significantly higher in men than in women[15-19]. However, this protective effect of the female sex diminishes after menopause, highlighting the importance of reproductive status in MASLD development[15-19]. Both the onset and the progression of MASLD are influenced by these factors. In a seminal meta-analysis of 54 studies, Balakrishnan et al. reported that women had approximately a 20% lower risk of MASLD compared to men[20]. While no significant sex difference was observed for the risk of MASH, women exhibited a 37% higher risk of advanced fibrosis than men[20].

Age further modifies the effect of sex on MASLD severity. In populations with a mean age of 50 years or older, women had substantially higher risks of MASH and advanced fibrosis, whereas these sex discrepancies were less pronounced in younger cohorts[20]. A recent study using data from the 1999-2006 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey found that high serum homocysteine levels (Hcy) are independently linked to a higher risk of hepatic fibrosis in MASLD, especially in men and postmenopausal women[21]. These findings underscore the importance of accounting for sex and menopausal status in future Hcy-lowering interventions targeting MASLD.

MASLD-cirrhosis

Shi et al., in their population-based retrospective cohort study of adults with cirrhosis, found that men had a significantly higher incidence of decompensated cirrhosis, HCC, and liver transplantation compared to women[22]. These findings suggest that the male sex is likely associated with worse liver-related outcomes, including MASLD-related cirrhosis. The increased risk of major adverse liver outcomes (MALO) in males with MASLD may be partially due to more frequent alcohol use, which can increase mortality even with moderate intake[23].

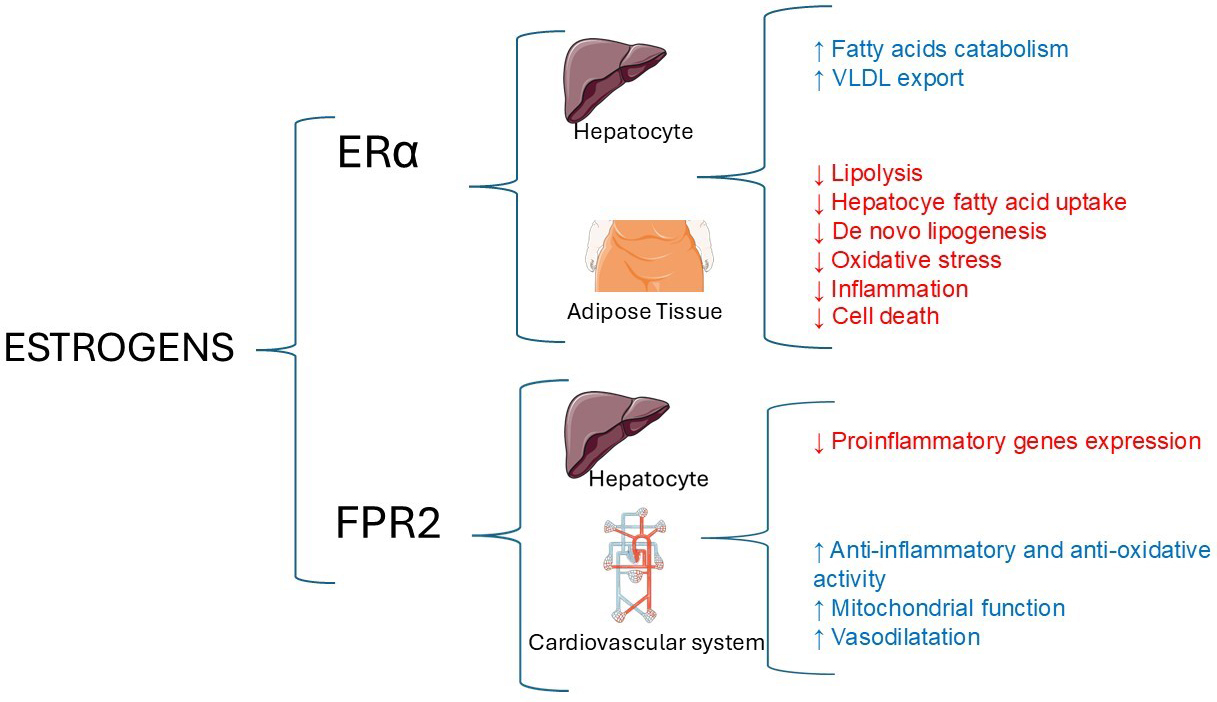

Sex discrepancies in MASLD-related cirrhosis may also be influenced at the molecular level. Females show higher expression of the liver formyl peptide receptor 2 (FPR2), an estrogen-regulated modulator of inflammation. FPR2 interacts with different metabolic pathways, including those involving choline, the pentose phosphate pathway, and glutamine metabolism, providing women with relative protection against MASLD progression[24].

Risks of extra-hepatic outcomes in MASLD

MASLD-associated cardiovascular disease

A recent meta-analysis by Jamalinia et al.[25], comprising thirty-six cohort studies with aggregate data on approximately 18.5 million individuals, has shown that MASLD is associated with a significantly higher risk of fatal or non-fatal cardiovascular disease (CVD) events in women compared to men (P-value for sex difference = 0.018). This suggests that MASLD eliminates the protection from CVD in women[25]. Our understanding of the potential pathomechanisms exacerbating the risk of CVD events among women with MASLD is preliminary and incomplete.

The development and progression of MASLD in women involves interactions between adipose tissue, the gut microbiome, and the liver, which can also affect sex-specific CVD risk. In all these processes, estrogens play a crucial role [Figure 1].

Figure 1. Main hepatic and extra-hepatic activities of estrogens. Estrogen receptor-α (Erα) and FPR2 play a crucial role in the sex-specific variations observed in the progression of MASLD, MASH, and specific extra-hepatic outcomes. The original illustration was generated using Servier Medical ART (SMART) and is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC BY 4.0), incorporating data from[24,26]. FPR2: Formyl peptide receptor 2; MASLD: metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease; MASH: metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis.

While the FPR2 may protect against CVD through its anti-inflammatory, anti-oxidative, and vasodilating effects[27], female-specific factors such as reproductive history, breast cancer treatment, autoimmune diseases, and pregnancy-related complications such as arterial hypertension and gestational diabetes can increase the risk of MASLD and future CVD events[25,27]. On the other hand, lactation may offer protection against MASLD and CVD due to metabolic and hormonal benefits[28]. Nevertheless, our understanding of these phenomena is still partial, and further research is required to elucidate the roles of genetics and hormonal factors in modulating CVD risk in women with MASLD.

MASLD-associated chronic kidney disease

MASLD is independently associated with an increased risk of chronic kidney disease (CKD)[29], with limited evidence suggesting a stronger association in men than in women. Large population-based studies show higher MASLD-related CKD risk in men, independent of shared cardiometabolic risk factors[30-32]. However, a German study found no statistically significant sex difference although a trend toward higher dialysis-requiring CKD in men was noted[33]. This sex-specific MASLD-related CKD risk might reflect greater susceptibility to renal disease in men, who more frequently exhibit visceral adiposity, severe insulin resistance, and heightened activation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system. These pathomechanisms synergize in promoting glomerular hyperfiltration, endothelial dysfunction, and fibrosis[34,35]. Moreover, androgens may exacerbate renal injury via pro-inflammatory and profibrotic pathways, while estrogens provide partial nephroprotection, particularly before menopause[35]. Additionally, MASLD-related liver fibrosis appears more closely linked to CKD progression in men, whereas in women, advanced MASLD tends to shift systemic risk toward cardiovascular, rather than renal outcomes[25]. Collectively, these mixed findings support additional investigations before drawing any firm conclusions.

MASLD-associated extra-hepatic cancers

In MASLD, breast cancer, colon cancer, and pancreatic adenocarcinoma occur 44% more often in women than in men, and the risk of their occurrences does not depend on the stages of liver fibrosis[36]. Conversely, HCC occurs more often in men than in women and is directly related to the stages of liver fibrosis, although it may also develop in non-cirrhotic MASLD[36,37].

The liver contains both estrogen and androgen receptors (ARs), which contribute to sex-based discrepancies in hepatic gene expression, immune function, and the risk of developing primary liver cancer[38]. The effects of gonadal hormones vary depending on patient sex and the severity of MASLD. Additionally, factors such as obesity, alcohol consumption, and tobacco use, more prevalent among men, as well as social determinants leading to gender-related disparities, may interact with hormonal pathways, thereby promoting liver injury[38].

Summary and strength of the evidence

Based on robust epidemiological evidence, MASLD is a significant global health concern, particularly common in certain geographical areas and with increasing rates in others. Disease prevalence peaks earlier in men than in women, with men generally having higher rates, but this gap closes after menopause. While women face increased risks of advanced fibrosis and associated conditions as they age, men experience more severe outcomes following cirrhosis. In terms of extrahepatic outcomes, MASLD raises cardiovascular risk and a greater likelihood of certain cancer types in women, while men seemingly have a higher risk of CKD.

PATHOGENESIS

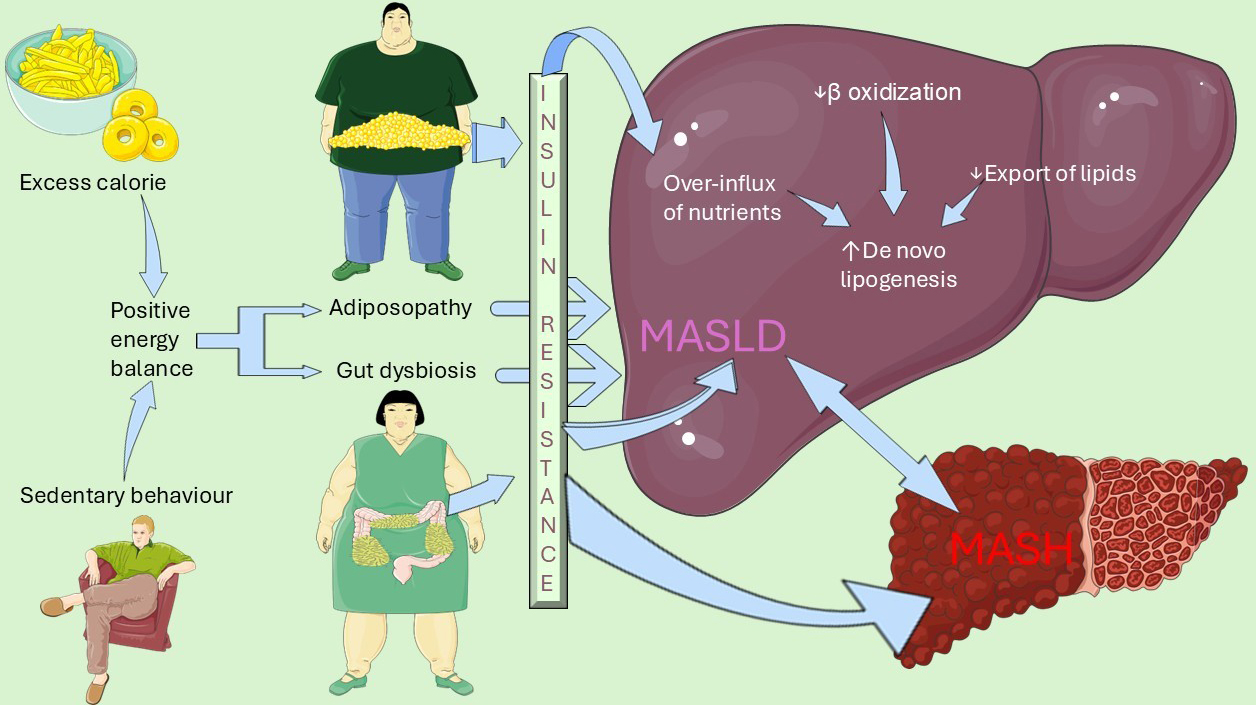

The general pathogenesis of MASLD and MASH involves both extra-hepatic and intra-hepatic determinants which are schematically illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Overview of MASLD/MASH pathogenesis. Schematic illustration of the central role played by insulin resistance in connecting extra-hepatic determinants with intrahepatic pathomechanism. The former primarily involves adiposopathy, defined as an expanded, inflamed and dysfunctional adipose tissue, and gut dysbiosis, namely decreased intestinal bacteria diversity. The latter comprises increased de novo lipogenesis and activated proinflammatory and pro-fibrotic pathways determining the progression from MASLD to MASH. This original illustration was generated using Servier Medical ART (SMART) and is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC BY 4.0), utilizing data notions from[10,13,18]. MASLD: Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease; MASH: metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis.

Role of sex in MASLD pathogenesis

Body fat distribution, sex-specific biology of adipose tissue, and gut microbiota play a key role[10]. Post-menopausal women behave similarly to men, whereas pre-menopausal women are protected from MASLD[18] due to estrogens. Estrogens, via estrogen receptor-α (Erα), increase the catabolism of fatty acids and their export from the hepatocyte into the bloodstream while downregulating de novo lipogenesis, steatogenesis, oxidative stress, inflammation, and cell death[26].

Growth hormone

The temporal pattern of pituitary growth hormone (GH) secretion is sex-specific in many species, with episodic release in males and more stable levels in females. This pattern represents a major component in establishing and maintaining the sexual dimorphism of hepatic gene transcription[39].

Sex hormones, metabolic function, and liver health

Low estrogen levels in females are linked to liver pathology, characterized by increased fat storage, impaired glucose tolerance, and alterations in the tricarboxylic acid cycle[40]. In males, either impaired signaling or abnormal levels of estrogen or testosterone are consistently associated with MASLD, visceral obesity, insulin resistance, and type 2 diabetes (T2D)[40]. Estrogens and androgens affect all types of liver cells: estrogens support DNA synthesis, endothelial function, and reduce inflammation; androgens promote cell growth, angiogenesis, collagen production, and pro-inflammatory effects, potentially increasing the risk of HCC in men[41]. More information on how sex hormones impact liver health can be found in additional sources[42-45].

Estrogen receptor-α signaling

This sexual dimorphism of the liver transcriptome becomes apparent in the ovariectomized mouse model and in severely obese women aged over 51, suggesting that masculinization of the female liver contributes to MASLD development in obese postmenopausal women[46]. This points to the hepatic Erα as a potential pharmacological target for preventing MASLD in post-menopausal women.

Complex interactions between GH, estrogen, and androgen signaling determine sex- and reproductive status-specific variations in body fat deposition. Clinically, two major phenotypes are discernible: android adiposity, characterized by visceral adipose tissue distribution, and pre-menopausal gynoid body fat distribution[10,47]. These macroscopic appearances have distinct functional consequences: visceral adiposity promotes hypertriglyceridemia, while subcutaneous body fat has the potential for fatty acid oxidation to ketone bodies and browning of adipose tissue under metabolically stressful conditions (e.g., fasting and exposure to cold temperatures)[10,47]. After menopause, women may tend to accumulate visceral adipose tissue with an android-type pattern, explaining why their risk of progressive MASLD increases[48]. Moreover, current evidence suggests a functional interaction between ERα and the patatin-like phospholipase domain-containing protein 3 (PNPLA3) p.I148M variant in the pathogenesis of fatty liver disease in women[49].

Estrogen-related receptor-α

Estrogen-related receptor-α (ERRα) is an orphan nuclear receptor that shares structural homology with estrogen receptor α but functions independently of direct estrogen binding. In hepatocytes, ERRα serves as a central transcriptional regulator of mitochondrial biogenesis, oxidative phosphorylation, and fatty-acid β-oxidation, thereby sustaining hepatic energy homeostasis[50]. Experimental and clinical studies indicate that ERRα expression and activity are sexually dimorphic, typically higher in females, where ERRα synergizes with estrogen signaling to restrain de novo lipogenesis and limit triglyceride accumulation[50]. Loss or inhibition of ERRα exacerbates diet-induced steatosis and insulin resistance[51,52]. These findings position ERRα as a promising therapeutic target in MASLD, particularly for post-menopausal women. In these subjects, waning estrogen levels may render ERRα-mediated pathways crucial for maintaining metabolic flexibility and protecting against progressive liver damage.

Sex interacts with gene variants involved in MASLD pathogenesis

Sex interacts with two of the main gene variants associated with MASLD. The PNPLA3 148M gene variant is a “gain of function” variant implicated in steatogenesis and is linked to an increased risk of MASLD development and progression[53,54]. This deleterious effect of PNPLA3 is more pronounced in females than in males, indicating that the risks of both MASH and significant fibrosis among those with the PNPLA3 gene variant are higher in women than in men[49].

On the other hand, the hydroxysteroid 17-beta dehydrogenase 13 (HSD17B13) gene variant is a “loss of function variant” responsible for reduced biogenesis of lipid droplets and is associated with a decreased risk of MASLD progression[55]. The protective effect of the HSD variant is more evident in post-menopausal women and becomes significant after the age of 50. Pre-menopausal women are already protected by estrogens, which mask the effect of the HSD gene variant, while in men, the risk of steatohepatitis does not change based on age[56].

Metabolic zonation

In the context of the liver containing various cell types and being functionally highly organized[57], both sexes have similar numbers of hepatic stellate cells. However, females have more hepatocytes per gram, a higher diploidy index, more Kupffer cells, and less collagen[38]. Structurally, lobules form the liver's units, while functionally, the hepatic acinus is key for blood flow[58,59]. Metabolic zonation refers to a zone-specific distribution of key enzymes and metabolic pathways across the hepatic acinus[60]. This concept has the potential to alter the spatial lipidomics within the liver, leading to the accumulation of lipids in specific zones, which may harbor cellular stress, inflammation, and fibrosis in a sex-specific manner[38,61].

Pulsatile GH release predominantly activates signal transducer and activator of transcription 5B (STAT5b) signaling, driving periportal gluconeogenesis, β-oxidation, and cholesterol biosynthesis in males. In contrast, the continuous GH profile favors the activation of the signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3), leading to lipogenesis and xenobiotic metabolism in the pericentral zone in females[38]. Taken together, these spatial and functional dynamics provide a cellular basis for understanding the differing susceptibility of men and women to MASLD, HCC, and autoimmune liver diseases. Additionally, they account for variations in the rate and pattern of disease progression, including fibrogenesis[38].

Intestinal microbiota

In addition to metabolic zonation, sex discrepancies in MASLD involve the gut microbiota. Studies in rat and mouse models of MASLD have shown significant sex variations in the composition and function of the gut microbiota. Female rodents often have higher microbial diversity and a different composition, including an abundance of beneficial bacteria such as Akkermansia, while males show reduced diversity and composition discrepancies that are linked to their varying responses in lipid metabolism and disease progression[62]. These sex-specific variations are influenced by genetics, hormones, and diet[63].

Evidence in humans is limited. One study found that key microbial taxa in women included Christensenella (more prevalent in controls) and Limosilactobacillus (more prevalent in MASLD), while in men, Beduinibacterium (less prevalent in MASLD) and Anaerotruncus (more prevalent in MASLD) were identified[64].

Due to the lack of research in humans, Puhan et al. utilized interpretable machine learning models to classify MASLD status and biological sex from human gut microbiome databases[65]. The findings suggest that variations in specific bacterial phyla may influence the risks of fibrosis, inflammation, and dysbiosis in a sex-specific manner, indicating that microbial composition may play a role in disease progression.

Innate immunity

While the sexual dimorphism of adaptive immunity remains understudied, in MASLD, innate immune cell responses differ between men and women[17]. In men, increased androgen signaling leads to heightened proinflammatory macrophage responses[66], as well as increased infiltration of neutrophils[67] and monocytes in the liver. Increased AR signaling may also account for the higher prevalence of MASLD in polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS)[42,68,69], a topic explored in Section PHYSIOLOGICAL, PATHOLOGICAL, AND PHARMACOLOGICAL MODIFIERS OF MASLD RISK of this review.

Sex-specific discrepancies in bile acid profiles in MASLD

A comprehensive analysis of the bile acid (BA) spectrum characteristics in MASLD requires careful consideration of sex-specific variations. These distinctions are critical when examining the pathophysiological changes that occur in MASLD. For instance, research has shown that women with MASLD exhibit significantly higher serum levels of lithocholic acid, glycolithocholic acid, and taurolithocholic acid compared to men[70]. In contrast, men with MASLD tend to have a higher proportion of primary to secondary BAs than their female counterparts[70]. These findings underscore the importance of accounting for sex as a biological variable in both clinical assessment and research studies focused on MASLD, as the underlying BA profiles may potentially affect disease progression and therapeutic responses differently in men and women.

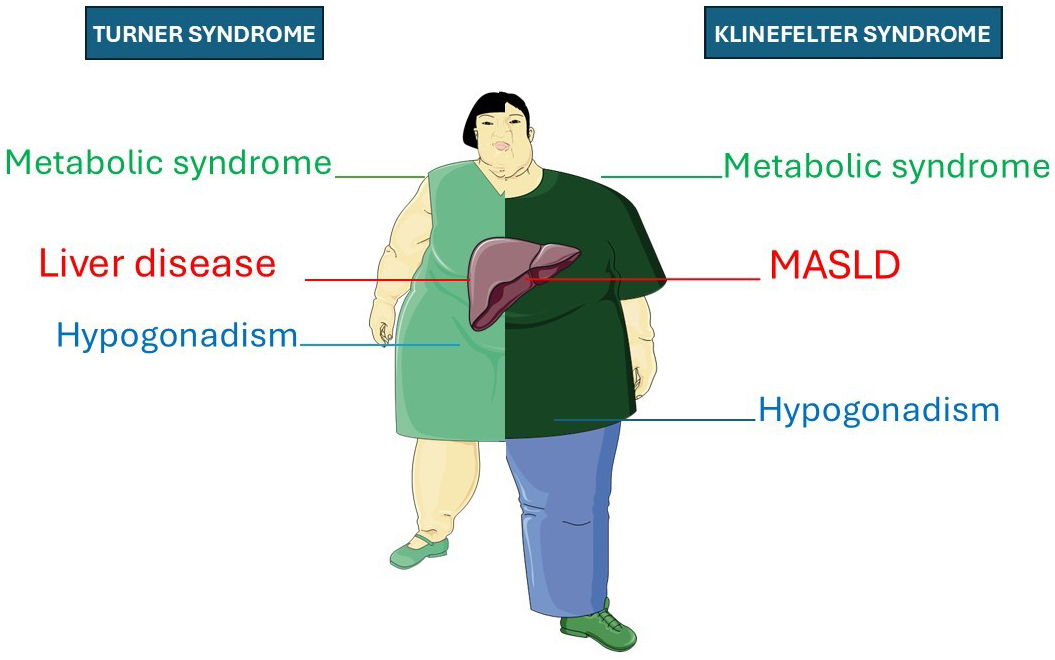

Role of sex chromosomes

Together with sex hormones, sex chromosomes themselves may influence metabolic regulation and liver health. This may be shown experimentally with the four-core genotype (FCG) mouse model, which allows researchers to separate the contributions of gonadal type and sex chromosome complement[71]. Turner syndrome (TS) and Klinefelter syndrome (KS) may serve as natural models to explore the metabolic impacts of altered X chromosome dosage demonstrating that this line of research has significant clinical importance.

TS occurs when one X chromosome is completely or partially lost in phenotypic females (45, X), while KS results from an extra X chromosome in phenotypic males (47, XXY). Individuals with either condition have a higher risk of liver disease compared to healthy controls of the same sex[72-74]. For example, TS individuals, compared to age-matched healthy controls, have significantly higher risks of raised liver enzymes (RLE), SLD, and significant/advanced liver fibrosis[75].

Liver disease in TS and KS can develop independently of estrogen and testosterone deficiencies[73,74]. In agreement, the above-cited meta-analysis found that hormone replacement therapy (HRT) was not associated with significant variations in the risks of RLE[75]. However, the risk differed by karyotype[75] supporting a dosage-dependent effect of the X chromosome on liver involvement, which may also be relevant in KS. KS individuals exhibit a MASLD prevalence of 45.1%[76]. Increased abdominal obesity and insulin resistance are observed in KS even before puberty, suggesting a direct influence of X chromosome dosage on metabolic risk, independent of androgen deficiency[77]. Consistently, testosterone replacement therapy does not fully correct metabolic abnormalities in KS[78].

Figure 3 summarizes the clinical similarities between TS and KS.

Figure 3. Schematic overview of clinical manifestations in TS and KS, with an emphasis on liver endpoints. This illustration highlights that both TS and KS are associated with the triad comprising metabolic syndrome, hypogonadism, and liver disease. The original illustration was drawn with Servier Medical Art under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 license (CC BY 4.0). MASLD: Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease; TS: Turner syndrome; KS: Klinefelter syndrome.

Summary and strength of the evidence

In conclusion, sex may significantly influence the risks of accumulating ectopic lipids within the liver. GH, estrogens and androgens interact with gene variants and modulate the functional activity of the liver. They also influence gut microbiota, immunity and BA profiles, potentially stimulating proinflammatory and profibrogenic pathways in the context of MASLD as discussed in Section EPIDEMIOLOGY AND COURSE OF DISEASE. Further research is necessary to clarify the subtle immuno-metabolic and hormonal pathomechanisms involved.

PHYSIOLOGICAL, PATHOLOGICAL, AND PHARMACOLOGICAL MODIFIERS OF MASLD RISK

Menarche and menopause

Wang et al. conducted a nested case-control study involving 1,861 cases of MASLD and 17,664 matched controls[79]. They found that increasing age at menarche (AAM) is protective, but factors such as parity (regardless of the number of children or age at first birth), surgical menopause compared to natural menopause, oral contraceptive use, and a longer duration of estrogen hormone therapy during menopause were all associated with an increased risk of MASLD. Supporting these findings, Si et al. demonstrated a linear association between AAM and MASLD risk[80]. Through a Mendelian randomization (MR) study, they discovered that for each additional year of AAM, the incidence of MASLD decreased by 19 % [odds ratio (OR) = 0.81, 95 % confidence interval (CI): 0.73-0.90]. Reverse MR analysis indicated that AAM unidirectionally causes MASLD[80]. Meta-analytic evidence confirms a strong association between menopause and MASLD risk, with a pooled OR of 2.37, regardless of age and metabolic factors[81]. This finding prompts the question of the potential impact of estrogen replacement therapy on MASLD during menopause.

Menopausal hormone therapy

The prevalence of MASLD detected through ultrasonography before and after menopausal hormone therapy (MHT) varies based on the route of estrogen administration. In a study of 368 menopausal women undergoing hormone therapy for 12 months, the prevalence before treatment was 24%, with no significant differences between those receiving transdermal or oral therapy[82]. However, after treatment, the prevalence of MASLD decreased from 24% to 17.3% in the transdermal group but increased from 25.3% to 29.4% in the oral group. Ultimately, the proportion of progressive disease (newly diagnosed or worsened severity) decreased after transdermal estrogen administration[82].

Although evidence indicates an increased risk of MASLD and MASH following menopause, existing studies are limited by methodological shortcomings. Currently, there are no targeted therapeutic strategies available to prevent MASLD onset or reverse disease progression in this patient population[83].

Polycystic ovary syndrome

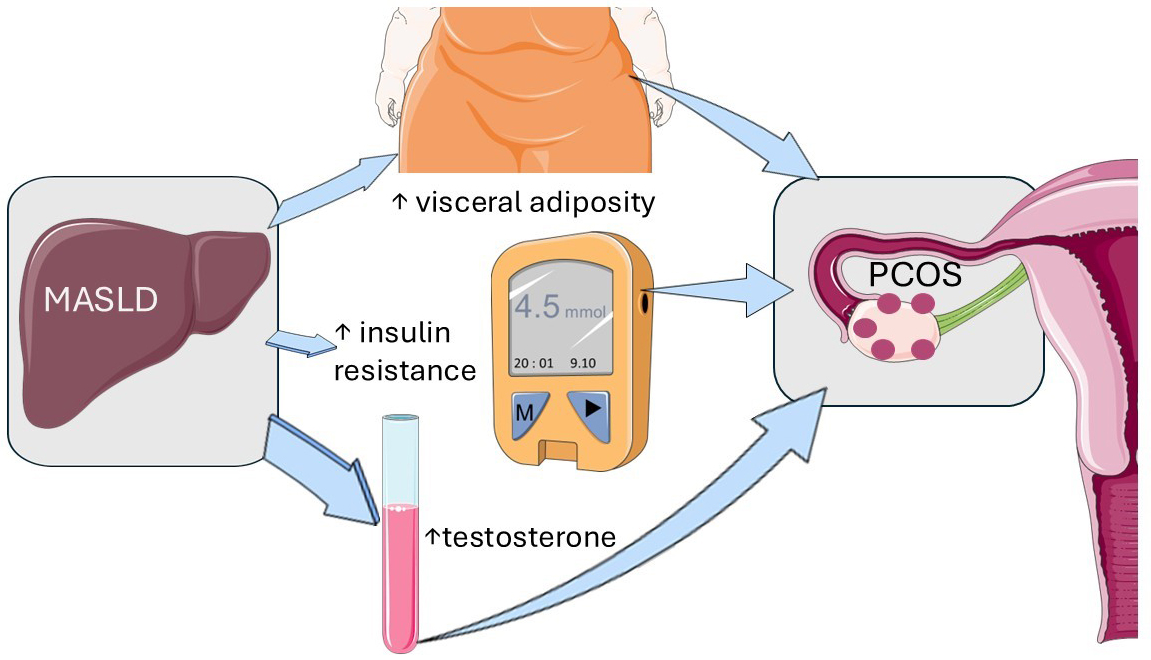

PCOS affects 6%-13% of reproductive-aged women and is characterized by hyperandrogenism, chronic anovulation, and infertility[84]. Liver involvement is common in PCOS, with individuals also at higher risk of MASH regardless of metabolic comorbidities[84]. Two recent studies demonstrate that MASLD causes PCOS through visceral adiposity, decreased insulin sensitivity, and increased testosterone levels[85,86].

Liu et al. conducted a bidirectional two-sample MR analysis to determine the causal association between MASLD and PCOS using data from a large-scale biopsy-proven MASLD genome-wide association study (GWAS) in European ancestries[85]. The study included 1,483 cases and 17,781 controls for the MASLD analysis, while the PCOS GWAS comprised 10,074 cases and 103,164 controls. Results showed that genetically predicted MASLD was causally associated with a higher risk of developing PCOS, with less evidence supporting the reverse causal association. The study also identified fasting insulin and sex hormones as potential mediating factors between MASLD and PCOS.

Wu et al. conducted a meta-analysis of twenty-four studies published up to July 2023, revealing that MASLD is associated with obesity, insulin resistance, and hyperandrogenemia in PCOS women in East Asia[86]. The findings of these two studies are visually represented in Figure 4.

Figure 4. MASLD causes PCOS. This graphical illustration depicts the endocrinological and metabolic mechanisms that lead from MASLD to PCOS through visceral adiposity, decreased insulin sensitivity, and increased testosterone levels. The notions illustrated here are based on the discussed references[86,87]. The original illustration was created using Servier Medical ART (SMART) and is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC BY 4.0). MASLD: Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease; PCOS: polycystic ovary syndrome.

Pregnancy and lactation

Meta-analytic evidence shows that MASLD is associated with a significantly increased risk of gestational diabetes mellitus and pre-eclampsia[88]. In terms of fetal outcomes, pregnancies complicated by MASLD are more likely to result in preterm birth and large-for-gestational-age infants. These findings emphasize the impact of MASLD on adverse pregnancy outcomes[87].

Conversely, breastfeeding protects both the mother and the infant against MASLD development and progression[28]. Lactation, which is metabolically equivalent to approximately 30-40 min of running, helps reset pregnancy-induced metabolic alterations[28]. Mothers who breastfeed for more than 6 months show a reduced risk of insulin resistance, diabetes, and metabolic syndrome[28,88]. Infants also benefit from maternal lactation through the development and colonization of the gut microbiota, maturation of the intestinal epithelium, and modulation of the immune system[28]. Moreover, docosahexaenoic acid contained in human milk and human milk-derived extracellular vesicles inhibits lipogenesis and fibrogenic pathways in the infant liver[28].

Summary and strength of the evidence

Solid evidence indicates that physiological, pathological, and pharmacological factors influence the risk of MASLD. For example, a later menarche is associated with a lower risk of MASLD, while factors such as parity, surgical menopause, oral contraceptive use, and prolonged estrogen therapy can increase the risk. The impact of MHT on MASLD risks varies depending on the route of estrogen administration, with transdermal estrogen showing beneficial effects and oral therapy increasing the risks. MASLD may play a causal role in PCOS through metabolic pathways involving visceral adiposity, insulin resistance and hyperandrogenism. Additionally, PCOS is often connected to MASH. MASLD also raises the risks of gestational diabetes, pre-eclampsia, pre-term birth, and large-for-gestational-age infants. Prolonged breastfeeding protects both mothers and infants from MASLD through various biological mechanisms. Further studies are needed to determine the most effective approaches to preventing or treating MASLD in post-menopausal individuals.

INFLUENCE OF SEX ON THE RESPONSES TO TREATMENT

MASLD treatment encompasses a variety of dimensions, ranging from lifestyle changes, pharmacologic therapy, HRT, and bariatric surgery. Extensive coverage of the available options has recently been published elsewhere[89-92]. Here we discuss the primary sex variations related to lifestyle changes and medical treatment. The latter includes modifications of cardiometabolic risk factors and liver-targeted therapies. Sex and gender discrepancies in the field of bariatric surgery for MASLD are covered elsewhere[93].

Lifestyle changes

Ten years ago, Vilar-Gomez et al. found that being female, along with metabolic and liver histology features, was a strong predictor of a reduced probability of improvement in the MASLD activity score (NAS)[94]. NAS is defined as the unweighted sum of scores for steatosis (0-3), lobular inflammation (0-3), and ballooning (0-2)[95]. Recent studies suggest that men respond better than women to dietary interventions in terms of weight loss and metabolic improvement[96], as shown in Table 1[97-102]. This disparity is most likely attributed to the higher baseline lean-body mass of men and resting energy expenditure that accelerates lipid mobilization when caloric intake is reduced. Moreover, androgen-driven, pulsatile GH signaling preferentially activates hepatic β-oxidation and promotes loss of visceral fat, whereas estrogen-dominant, continuous GH patterns in pre-menopausal women favor lipogenesis and subcutaneous fat preservation, potentially dampening diet-induced improvements in hepatic steatosis. Sex discrepancies in appetite-regulating hormones, with men exhibiting greater post-diet satiety and smaller ghrelin rebounds, may further enhance male adherence to hypocaloric regimens.

| Author, year[Ref] | N, Sex, (Age) | Intervention | Findings | Conclusions |

| Bedard et al., 2014[97] | N = 69 M: 37 (42.6 ± 7.3) F: 32 (41.2 ± 7.3) | 4-week Mediterranean diet | A sex-by-time interaction for plasma insulin iAUC was found (men: -17.8%, P = 0.02; women: +9.4%, P = 0.63; P for sex-by-time interaction = 0.005). A sex-by-time interaction was also observed for insulin sensitivity (Cederholm index, P = 0.03), with only men showing improvements (men: +8.1%, P = 0.047; women: -5.9%, P = 0.94) | Men exhibited lower postprandial insulinemia levels |

| Leblanc et al., 2014[98] | M: 64 (41 ± 7.9) F: 59 (41.8 ± 6.7) | 12-week Mediterranean diet | Dietary changes were associated with a reduced waist circumference. As for metabolic variables, changes observed in total-cholesterol to HDL-cholesterol ratio, triglyceride levels and triglycerides to HDL-cholesterol ratio were more pronounced in men than in women after the intervention as well as at follow-up (P ≤ 0.03) | Men demonstrated a significantly improved metabolic profile |

| D’Abbondanza et al., 2020[99] | N = 70 M: 28 (20-62) F: 42 (17-67) | 25-day very low-carbohydrate ketogenic diet | Males had a higher reduction in waist circumference (8.5 cm; IQR = 5.5-11.0 vs. 6.0 cm, IQR = 3.0-10.0 cm; P = 0.032) compared to females. Additionally, males exhibited a greater reduction in both HOMA-IR and HbA1c, which was observed in males compared to pre-menopausal females (4.57 ± 4.56 vs. 0.44 ± 1.72, P = 0.030 for HOMA-IR; 0.40, IQR 0.23-1.05 vs. 0.05, IR -0.2 to 0.4, P = 0.034 for HbA1c). Liver steatosis grade significantly decreased in males compared to pre- and post-menopausal females (P = 0.001 vs. 0.020 and 0.083, respectively) | Men showed better responses in terms of body weight loss and improvement in MASLD than pre-menopausal women |

| Trouwborst et al., 2021[100] | N = 782 M: 276 (42.5 ± 6.0) F: 506 (41 ± 6.3) | 6-month low-calorie diet | Improvements in HOMA-IR, muscle and hepatic insulin sensitivity, triacylglycerol, HDL-, LDL- and total cholesterol, diastolic blood pressure, cholesterol esters, sphingomyelins and adiponectin were more pronounced in men than in women (std. β range: 0.073-0.144, all P < 0.05), after adjusting for weight change | Even though both sexes experienced beneficial changes in cardiometabolic risk factors from a low-calorie diet, men were found to be more responsive than women in terms of these parameters |

| Vitale et al., 2023[101] | N = 156 M: 74 (55.7 ± 10.7) F: 82 (55.1 ± 10.7) | 12-week high- vs. low-glycemic index diet | In women, the high-glycemic index diet induced significantly higher (23%, P < 0.05) 8-h average plasma glucose concentrations compared to the low-glycemic index diet already on the first day of the intervention. The difference increased to 37% (P < 0.05) after 12 weeks of the diet. Conversely, there were no significant differences between the two diets in men. These results were confirmed by a two-way analysis of variance, which showed a statistically significant interaction between the effects of sex and diet on the glucose profile after breakfast and lunch (F = 7.887, P = 0.006) | Women showed greater metabolic improvement than men |

| Muscogiuri et al., 2024[102] | N = 42 M: 21 (37.7 ± 10.7) F: 21 (32.7 ± 8.7) | 45-day very low-energy ketogenic diet | Men responded better in terms of weight loss (Δ% = - 11.63 ± 1.76 vs. - 8.95 ± 1.65 kg, P < 0.001), fat mass (Δ% = - 30.84 ± 12.00 vs. -21.36 ± 4.65 kg, P = 0.002), and reduction in inflammation assessed with hs-CRP levels (Δ% = - 41.42 ± 21.35 vs. - 22.38 ± 17.30 mg/L, P = 0.003) than premenopausal women | Men improved more than young women |

A recent study has shown that nutrition during the first 1,000 days of life significantly impacts the risk of developing MASLD and liver complications in adulthood[103]. The authors noted that early-life sugar rationing provided a more significant protective effect against cirrhosis in males, suggesting potential sex-specific sensitivities to early dietary exposures. These findings imply that the predisposition to develop hepatic complications of MASLD may be sex-specific from early infancy and should be further confirmed before being implemented in clinical practice.

Antidiabetic and anti-obesity drug therapy

Yang et al. conducted a meta-analysis of fourteen studies, which revealed that women treated with various glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1RAs) lost more weight than men[104]. Meta-regression analysis indicated that sex discrepancies become more pronounced as the degree of weight loss increases. Several mechanisms may explain the heightened efficacy of GLP-1RAs in women. These include different pharmacokinetics, increased satiety, more significant improvement in the pathobiology of adipose tissue, and greater adherence to treatment among women[104].

In the context of an emerging research avenue, a stable glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1)-estradiol conjugate was developed to selectively deliver estrogen to cells expressing the GLP-1 receptor without causing unwanted side effects while maximizing efficacy[48]. Laboratory studies have conflicting results, and there are no published human studies. However, this novel synthetic molecule clearly highlights the unexplored research pathways within the field of sex discrepancies in MASLD.

Lipid-lowering therapy

Although lipid-lowering therapy is equally effective in both sexes, real-world studies indicate that women with comparable risk profiles are less likely than men to receive these treatments and less likely to achieve guideline-recommended low-density lipoprotein cholesterol goals[105]. This difference should be attributed to “gender” rather than “sex”, as it is influenced by patient-related, physician-related, and societal factors. Additional studies are needed to specifically ascertain whether lipid-lowering therapies exert sex-specific effects on MASLD pathobiology.

Resmetirom

At the time of writing, Resmetirom and Semaglutide are the only two licensed drugs for treating MASH[106]. Recent work by Jamalinia et al.[93] has identified sex-specific variations associated with medication. The authors point out that, while overall treatment effects were similar across sexes, nuanced dose-dependent variations in response may be due to underlying sex-related discrepancies in lipid metabolism or thyroid hormone signaling. These observations emphasize the need for further research into sex-based dosing strategies to optimize personalized treatment approaches for MASH.

Hormonal therapies

Testosterone replacement therapy

Regarding testosterone replacement in hypogonadal men, a recent systematic review with meta-analysis[107] suggests improved liver outcomes without any additional adverse events. However, further research is needed to address the limitations of published studies. These include variations in testosterone dosages, administration methods, and timings, inconsistent risk of bias, varying study designs, and follow-up periods.

Effects of estrogen-modifiers (Tamoxifen)

Tamoxifen rarely causes idiosyncratic liver injury within the first six months of treatment, but is more commonly associated with SLD and steatohepatitis after prolonged use[108]. Bruno et al. first reported that tamoxifen increases the risk of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, particularly in overweight and obese women with features of metabolic syndrome[109], suggesting that this drug may exacerbate underlying metabolic dysfunction. A recent prospective longitudinal study of Caucasian breast cancer patients found no significant changes in liver steatosis, controlled attenuation parameter (CAP) values, or liver and lipid parameters after two years of tamoxifen treatment[110]. This suggests that there were no detectable tamoxifen-related hepatic adverse events such as steatosis, fibrosis, or cirrhosis during the study period. However, it is noted that the duration of follow-up may not have been long enough to capture longer-term liver outcomes. Protracted follow-up studies are therefore needed to better understand the effects of estrogen-modifiers on liver health.

Effects of antiandrogens on MASLD

The two most commonly used anti-androgenic drugs are cyproterone acetate (CPA) and bicalutamide. Evidence from men treated with antiandrogens for prostate cancer suggests various types of acute liver damage, while a systematic analysis of SLD and MASLD in this context requires further clarification.

Bessone et al. reported on a population of 22 male patients who developed severe acute liver damage due to CPA therapy, which can be fatal and may resemble autoimmune drug-induced liver injury (DILI)[111]. Flutamide and bicalutamide may increase the risk of liver injury compared to enzalutamide, apalutamide, and darolutamide[112]. The low number of cases and limited follow-up detract from the robustness of the published evidence. Further studies are needed to systematically assess the effects of antiandrogens on the risks of MASLD development and progression.

Gender affirming hormone therapy

Transgender health, which includes the interaction between sex hormones and liver disease, is becoming increasingly relevant in clinical practice with the goal of reducing barriers to care[97]. Gender affirming hormone therapy (GAHT) used by transgender individuals may offer valuable insights into the hormonal effects on MASLD[113].

In a study by Sluková et al., 15 transgender women and 20 transgender men undergoing GAHT for six months were evaluated[114]. Transgender women received either transdermal or oral estrogen, often in combination with CPA, while transgender men were treated with intramuscular or transdermal testosterone. Magnetic resonance imaging and spectroscopy revealed significant changes in body fat distribution, including increased subcutaneous fat and decreased visceral adipose tissue, with no significant changes in intrahepatic fat content[114]. However, the small sample sizes, lack of histological characterization of patients, and limited follow-up period weaken the evidence provided by these studies. Further research is necessary to determine if long-term use of GAHT can also improve ectopic intrahepatic liver fat content.

Sex-specific side effects of MASH treatment

Resmetirom does not exhibit significant pharmacokinetic sex-specific discrepancies. However, hormonal changes such as increased testosterone and sex hormone binding globulin levels have been reported in both males and females, with a higher follicle-stimulating hormone/luteinizing hormone ratio found in men[115]. Endocrine and liver/thyroid monitoring are important, and more long-term data are needed to assess safety and drug interactions.

Semaglutide safety profiles demonstrate certain sex-based disparities. Women have been observed to experience a higher incidence of nausea and vomiting, as well as potentially greater weight loss. In men, notable benefits may include improvements in cardiovascular and kidney outcomes, along with enhancements in testosterone levels and sexual function[116]. However, the incidence of serious adverse events appears to be comparable between sexes.

Safety considerations in pregnancy and lactation

The safety of resmetirom during pregnancy and lactation has not been established. Use of this drug is recommended only if the potential benefits outweigh the possible risks, as animal studies have indicated potential fetal harm. Patients should be monitored for adverse effects such as liver dysfunction, and newborns should be observed with caution. A pregnancy registry is available to track outcomes, and healthcare providers should be notified if the patient is pregnant or breastfeeding[117].

Semaglutide is not recommended for use during pregnancy because animal studies indicate potential fetal risks. Healthcare professionals advise discontinuing semaglutide at least two months before conception. During lactation, injectable formulations are generally discouraged due to insufficient data in humans, although preliminary research suggests minimal transfer into breast milk. Oral semaglutide should be avoided during breastfeeding due to the presence of the absorption enhancer sodium N-(8-[2-hydroxybenzoyl]amino)caprylate (SNAC)[118].

Summary and strength of the evidence

Accumulating and yet insufficient evidence suggests that sex plays a role in MASLD treatment outcomes, impacting responses to lifestyle changes and pharmacotherapy. Typically, women show less improvement in MASLD scores than men and are less responsive to dietary interventions. Early nutrition affects liver health differently based on sex, with males benefiting more from early sugar restrictions. Women tend to experience greater weight loss on GLP-1RA drugs, possibly due to an interaction of biological and behavioral factors. Experimental treatments such as GLP-1-estradiol conjugates may provide future sex-specific options, although data in humans are currently lacking. Women are less likely than men to achieve cholesterol targets, highlighting gender-related disparities. Further studies are needed to determine the endocrinological safety of resmetirom and whether resmetirom and semaglutide require sex-specific dosages and monitoring. Limited evidence suggests that testosterone replacement may improve liver outcomes in hypogonadal men, but this conclusion is hindered by study design limitations. While tamoxifen rarely causes acute liver injury, it may induce steatohepatitis in some women, necessitating longer follow-up periods. Anti-androgens pose a risk of acute liver damage in men, although data on this are scarce. Additional research is required to understand the long-term effects of GAHT on liver fat content and MASLD progression. Bariatric surgery has been shown to improve long-term MASLD outcomes for individuals of all sexes, but tailoring timing and management to sex-specific risks can enhance safety and efficacy. For example, providing earlier referrals for men may increase benefits and reduce complication rates[93].

CONCLUSION AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS

Sex discrepancies influence the epidemiology, pathogenesis, clinical outcomes, and therapeutic responses of MASLD throughout the reproductive lifespan in both men and women. These prominent variations arise from the coordinated interplay between sex chromosomes and sex hormones, which together modulate the molecular and physiological mechanisms underlying liver disease. Although these findings require further confirmation, they provide proof-of-concept evidence that could potentially support sex-specific medical approaches. Recognizing and accounting for this sexual dimorphism is essential in the design, analysis, and interpretation of both experimental and clinical studies. Consideration of sex and reproductive life should be included in MASLD guidelines, and MASLD should be considered in guidelines on HRT, PCOS, TS, and KS.

Further investigation into sexual dimorphism in MASLD should recognize that widely used non-invasive diagnostic tools (such as the use of serum biomarkers, non-invasive algorithms, or imaging techniques instead of liver histology) are largely derived from male-predominant populations and apply uniform cut-offs. Sex differences in MASLD prevalence, disease progression, and prognostication may influence the diagnostic performance of unisex thresholds within MASLD risk assessment algorithms, leading to sex-specific misclassification, particularly in women. However, data on sex-specific screening or treatment thresholds to optimize management remain limited.

It is important to address adaptive immunity, intestinal microbiota, changes in the BA pool, the impact of PCOS on MASLD, and the role of exogenous sex hormones and corresponding anti-hormones. Additionally, future research should aim to unravel the specific roles of sex hormones and sex chromosomes in the development and progression of MASLD across different life stages. Mechanistic studies are necessary to understand how estrogen, androgen, and X-linked gene dosage regulate hepatic lipid metabolism, inflammation, and fibrogenesis. It remains unclear which mechanisms are most likely to be sex-specific therapeutic targets, such as estrogen signaling, adipose distribution, and muscle mass. Similarly, the potential impact of sex on responses to lifestyle interventions, GLP-1RAs, pioglitazone, SGLT2 inhibitors, resmetirom, and semaglutide needs further investigation.

Longitudinal and interventional studies should also investigate how menopause, HRT, and sex-specific comorbidities mechanistically influence disease course and response rates to lifestyle changes, medical and surgical (bariatric and metabolic) treatment of metabolic dysfunction and its hepatic outcomes.

Population-based research must ensure balanced sex representation and adopt sex-stratified analyses. Establishing sex-specific thresholds for diagnostic tools and biomarkers will enhance diagnostic accuracy and clinical relevance. Integrating multi-omics approaches, including transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics, and epigenomics, may reveal molecular signatures explaining sex-related susceptibility to MASLD and its extrahepatic complications. Finally, clinical trials should systematically incorporate sex-based analyses as a standard requirement to improve external validity and promote equitable care. Collaborative efforts among clinicians, researchers, patients, healthcare providers, and policymakers will be crucial in translating these insights into effective, personalized prevention and treatment strategies for both women and men with MASLD.

DECLARATIONS

Acknowledgments

Graphical Abstract was partly generated using Servier Medical Art, provided by Servier, licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Authors’ contributions

Made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the review and to the analysis and interpretation of the literature: Lonardo A, Jamalinia M, Weiskirchen R.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Financial support and sponsorship

None.

Conflicts of interest

Lonardo A is the Editor-in-Chief and Founding Editor of Metabolism and Target Organ Damage. Weiskirchen R is an Associate Editor of Metabolism and Target Organ Damage. Neither of them was involved in any steps of the editorial process, including reviewers’ selection, manuscript handling, or decision-making. Jamalinia M has declared that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026.

REFERENCES

2. Bae J, Han E, Lee HW, et al. ; Fatty Liver Research Group of the Korean Diabetes Association. Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease in type 2 diabetes mellitus: a review and position statement of the fatty liver research group of the Korean Diabetes Association. Diabetes Metab J. 2024;48:1015-28.

3. Esposito M, Rimauro I, Frattolillo V, et al. MASLD in childhood as a multisystem health challenge beyond the liver. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2025.

4. Li X, Zhou XD, Wu J, et al. Pediatric MASLD in China: epidemiology, screening, diagnosis, and management. Lancet Reg Health West Pac. 2025;64:101717.

5. Yadav AK, MacNeill JJ, Krylov A, et al. Sex- and age-associated factors drive the pathophysiology of MASLD. Hepatol Commun. 2024;8:e0523.

6. Mauvais-Jarvis F, Bairey Merz N, Barnes PJ, et al. Sex and gender: modifiers of health, disease, and medicine. Lancet. 2020;396:565-82.

7. Arnold AP, Klein SL, McCarthy MM, Mogil JS. Male-female comparisons are powerful in biomedical research - don’t abandon them. Nature. 2024;629:37-40.

8. Lonardo A, Suzuki A. Sex differences in alcohol-related liver disease, viral hepatitis, metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease, and hepatocellular carcinoma. Explor Dig Dis. 2025;4:1005101.

9. Lonardo A, Trande P. Are there any sex differences in fatty liver? A study of glucose metabolism and body fat distribution. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2000;15:775-82.

10. Lonardo A, Nascimbeni F, Ballestri S, et al. Sex differences in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: state of the art and identification of research gaps. Hepatology. 2019;70:1457-69.

11. World Health Organization. Gender and Health. Available from: https://www.who.int/health-topics/gender#tab=tab_1. [Last accessed on 29 January 2026].

12. Jamalinia M, Lonardo A, Weiskirchen R. Sex and gender differences in liver fibrosis: pathomechanisms and clinical outcomes. Fibrosis. 2024;2:10006.

13. Page A, Mann DA. Epigenetic regulation of liver fibrosis. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2015;39 Suppl 1:S64-8.

14. Feng G, Targher G, Byrne CD, et al. Global burden of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease, 2010 to 2021. JHEP Rep. 2025;7:101271.

15. Ballestri S, Nascimbeni F, Baldelli E, Marrazzo A, Romagnoli D, Lonardo A. NAFLD as a sexual dimorphic disease: role of gender and reproductive status in the development and progression of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and inherent cardiovascular risk. Adv Ther. 2017;34:1291-326.

16. Burra P, Bizzaro D, Gonta A, et al. ; Special Interest Group Gender in Hepatology of the Italian Association for the Study of the Liver (AISF). Clinical impact of sexual dimorphism in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH). Liver Int. 2021;41:1713-33.

17. Booijink R, Ramachandran P, Bansal R. Implications of innate immune sexual dimorphism for MASLD pathogenesis and treatment. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2024;45:614-27.

18. Cherubini A, Della Torre S, Pelusi S, Valenti L. Sexual dimorphism of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease. Trends Mol Med. 2024;30:1126-36.

19. Penmetsa R, Kapil S, VanWagner LB. Sex and gender differences in metabolic dysfunction-associated liver disease. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2025.

20. Balakrishnan M, Patel P, Dunn-Valadez S, et al. Women have a lower risk of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease but a higher risk of progression vs men: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;19:61-71.e15.

21. Suzuki M, Kim HY, Reed MC, et al. Elevated homocysteine is associated with liver fibrosis in metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease in a sex- and menopause-specific manner. Gastro Hep Adv. 2026;5:100800.

22. Shi Y, Zhang X, Wong T, et al. Sex differences in risk of adverse liver events in patients with cirrhosis. JAMA Netw Open. 2025;8:e2523674.

23. Acierno C, Barletta F, Caturano A, et al. Alcohol consumption and liver metabolism in the era of MASLD: integrating nutritional and pathophysiological insights. Nutrients. 2025;17:2229.

24. Lee C, Kim J, Han J, et al. Formyl peptide receptor 2 determines sex-specific differences in the progression of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and steatohepatitis. Nat Commun. 2022;13:578.

25. Jamalinia M, Zare F, Mantovani A, Targher G, Lonardo A. Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease and sex-specific risk of fatal and non-fatal cardiovascular events: a meta-analysis. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2025;27:5171-81.

26. Meda C, Dolce A, Della Torre S. Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease across women’s reproductive lifespan and issues. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2025;31:327-32.

27. Taylor LC, Arthur G, de Carvalho Cruz M, Stec DE, Badmus OO. Contribution of sex differences to the development of cardiovascular disease in metabolic-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD). Int J Transl Med (Basel). 2024;4:782-809.

28. Lonardo A, Suzuki A. Concise review: breastfeeding, lactation, and NAFLD. An updated view of cross-generational disease transmission and prevention. Metab Target Organ Damage. 2023;3:16.

29. Mantovani A, Petracca G, Beatrice G, et al. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and risk of incident chronic kidney disease: an updated meta-analysis. Gut. 2022;71:156-62.

30. Yan T, Zhang X, Wong T, Cheung R, Nguyen MH. Sex differences in adverse liver and nonliver outcomes in steatotic liver disease. JAMA Netw Open. 2024;7:e2448946.

31. Park H, Dawwas GK, Liu X, Nguyen MH. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease increases risk of incident advanced chronic kidney disease: a propensity-matched cohort study. J Intern Med. 2019;286:711-22.

32. Sinn DH, Kang D, Jang HR, et al. Development of chronic kidney disease in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a cohort study. J Hepatol. 2017;67:1274-80.

33. Kaps L, Labenz C, Galle PR, Weinmann-Menke J, Kostev K, Schattenberg JM. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease increases the risk of incident chronic kidney disease. United European Gastroenterol J. 2020;8:942-8.

34. Arner P, Viguerie N, Massier L, et al. Sex differences in adipose insulin resistance are linked to obesity, lipolysis and insulin receptor substrate 1. Int J Obes (Lond). 2024;48:934-40.

35. Harvey BJ, Alvarez de la Rosa D. Sex differences in kidney health and disease. Nephron. 2025;149:77-103.

36. Lonardo A, Stefan N, Mantovani A. Widening research horizons on metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease and cancer. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2025;36:610-3.

37. Shi Y, Taherifard E, Saeed A, Saeed A. MASLD-Related HCC: A comprehensive review of the trends, pathophysiology, tumor microenvironment, surveillance, and treatment options. Curr Issues Mol Biol. 2024;46:5965-83.

38. Matz-Soja M, Berg T, Kietzmann T. Sex-related variations in liver homeostasis and disease: From zonation dynamics to clinical implications. J Hepatol. 2026;84:181-93.

39. Brie B, Ramirez MC, De Winne C, et al. Brain control of sexually dimorphic liver function and disease: the endocrine connection. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2019;39:169-80.

40. Kasarinaite A, Sinton M, Saunders PTK, Hay DC. The influence of sex hormones in liver function and disease. Cells. 2023;12:1604.

41. Toniutto P, Shalaby S, Mameli L, et al. ; Special Interest Group Gender in Hepatology of the Italian Association for the Study of the Liver (AISF). Role of sex in liver tumor occurrence and clinical outcomes: a comprehensive review. Hepatology. 2024;79:1141-57.

42. Weiskirchen R, Lonardo A. The ovary-liver axis: molecular science and epidemiology. Int J Mol Sci. 2025;26:6382.

43. Xu L, Yuan Y, Che Z, et al. The Hepatoprotective and hepatotoxic roles of sex and sex-related hormones. Front Immunol. 2022;13:939631.

44. Xega V, Liu JL. Beyond reproduction: unraveling the impact of sex hormones on cardiometabolic health. Med Rev (2021). 2024;4:284-300.

45. Weiskirchen R, Lonardo A. Sex hormones and metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2025;26:9594.

46. Meda C, Benedusi V, Cherubini A, Valenti L, Maggi A, Della Torre S. Hepatic estrogen receptor alpha drives masculinization in post-menopausal women with metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease. JHEP Rep. 2024;6:101143.

47. Lonardo A, Suzuki A. Sexual dimorphism of NAFLD in adults. Focus on clinical aspects and implications for practice and translational research. J Clin Med. 2020;9:1278.

48. Milani I, Parrotta ME, Colangeli L, et al. Sex differences in MASLD after age 50: presentation, diagnosis, and clinical implications. Biomedicines. 2025;13:2292.

49. Cherubini A, Ostadreza M, Jamialahmadi O, et al. ; EPIDEMIC Study Investigators. Author Correction: interaction between estrogen receptor-α and PNPLA3 p.I148M variant drives fatty liver disease susceptibility in women. Nat Med. 2024;30:1212.

50. Tripathi M, Yen PM, Singh BK. Estrogen-related receptor alpha: an under-appreciated potential target for the treatment of metabolic diseases. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21:1645.

51. B'chir W, Dufour CR, Ouellet C, et al. Divergent role of estrogen-related receptor α in lipid- and fasting-induced hepatic steatosis in mice. Endocrinology. 2018;159:2153-64.

52. Chen CY, Li Y, Zeng N, et al. Inhibition of estrogen-related receptor α blocks liver steatosis and steatohepatitis and attenuates triglyceride biosynthesis. Am J Pathol. 2021;191:1240-54.

53. Weiskirchen R, Lonardo A. PNPLA3 as a driver of steatotic liver disease: navigating from pathobiology to the clinics via epidemiology. J Transl Genet Genom. 2024;8:355-77.

54. Wang Y, Hong S, Hudson H, et al. PNPLA3(148M) is a gain-of-function mutation that promotes hepatic steatosis by inhibiting ATGL-mediated triglyceride hydrolysis. J Hepatol. 2025;82:871-81.

55. Mahmood S, Morrice N, Thompson D, et al. Hydroxysteroid 17β-dehydrogenase 13 (Hsd17b13) knockdown attenuates liver steatosis in high-fat diet obese mice. Exp Physiol. 2025;110:1071-86.

56. Vilar-Gomez E, Pirola CJ, Sookoian S, Wilson LA, Liang T, Chalasani N. The protection conferred by HSD17B13 rs72613567 polymorphism on risk of steatohepatitis and fibrosis may be limited to selected subgroups of patients with NAFLD. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2021;12:e00400.

58. Ricken T, Werner D, Holzhütter HG, König M, Dahmen U, Dirsch O. Modeling function-perfusion behavior in liver lobules including tissue, blood, glucose, lactate and glycogen by use of a coupled two-scale PDE-ODE approach. Biomech Model Mechanobiol. 2015;14:515-36.

59. Lautt WW. Overview. In Granger DN, Granger J, Editors. Hepatic Circulation: Physiology and Pathophysiology. San Rafael (CA): Morgan & Claypool Life Sciences; 2009. pp. 7-18.

60. Kietzmann T. Metabolic zonation of the liver: the oxygen gradient revisited. Redox Biol. 2017;11:622-30.

61. Seubnooch P, Montani M, Dufour JF, Masoodi M. Spatial lipidomics reveals zone-specific hepatic lipid alteration and remodeling in metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis. J Lipid Res. 2024;65:100599.

62. Kim YS, Unno T, Kim BY, Park MS. Sex differences in gut microbiota. World J Mens Health. 2020;38:48-60.

63. Org E, Mehrabian M, Parks BW, et al. Sex differences and hormonal effects on gut microbiota composition in mice. Gut Microbes. 2016;7:313-22.

64. Mogna-Peláez P, Riezu-Boj JI, Milagro FI, et al. Sex-dependent gut microbiota features and functional signatures in metabolic disfunction-associated steatotic liver disease. Nutrients. 2024;16:4198.

65. Puhan S, Rekha SS, Sahu K, et al. Visiting MASLD through the lens of sex, immunity, and microbial interactions. Discov Med. 2025;2:236.

66. Pérez S, Rius-Pérez S. Macrophage polarization and reprogramming in acute inflammation: a redox perspective. Antioxidants (Basel). 2022;11:1394.

67. Zhou Z, Xu MJ, Cai Y, et al. Neutrophil-hepatic stellate cell interactions promote fibrosis in experimental steatohepatitis. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;5:399-413.

68. Guo Z, Wu Q, Xie P, Wang J, Lv W. Immunomodulation in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: exploring mechanisms and applications. Front Immunol. 2024;15:1336493.

69. Wang K, Li Y, Chen Y. Androgen excess: a hallmark of polycystic ovary syndrome. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2023;14:1273542.

70. Lyu S, Yang J, Xin X, et al. Characteristics of serum bile acid profiles among individuals with metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease. BMC Gastroenterol. 2025;25:334.

71. Wiese CB, Avetisyan R, Reue K. The impact of chromosomal sex on cardiometabolic health and disease. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2023;34:652-65.

72. Twohig P, Li L, Danford D, Craft M, Yetman AT. Prevalence of hepatic steatosis and fibrosis in Turner syndrome: A prospective case-control study. Liver Int. 2024;44:1309-15.

73. Singh I, Noel G, Barker JM, et al. Hepatic abnormalities in youth with Turner syndrome. Liver Int. 2022;42:2237-46.

74. Davis SM, Nokoff NJ, Furniss A, et al. Population-based assessment of cardiometabolic-related diagnoses in youth with Klinefelter syndrome: a PEDSnet study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2022;107:e1850-9.

75. Jamalinia M, Zare F, Mantovani A, Targher G, Lonardo A. Meta-analysis: liver disease burden and associated factors in turner syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2025. Epub 2025 Nov 14.

76. Marrone A, Allosso F, Caturano A, et al. Metabolic Dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease in klinefelter syndrome: high prevalence uncovers an unmet need. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2025. dgaf479. Epub 2025 Aug 29.

77. Mameli C, Fiore G, Sangiorgio A, et al. Metabolic and nutritional aspects in paediatric patients with klinefelter syndrome: a narrative review. Nutrients. 2022;14:2107.

78. Chang S, Skakkebaek A, Davis SM, Gravholt CH. Morbidity in Klinefelter syndrome and the effect of testosterone treatment. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 2020;184:344-55.

79. Wang J, Wu AH, Stanczyk FZ, et al. Associations between reproductive and hormone-related factors and risk of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in a multiethnic population. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;19:1258-1266.e1.

80. Si G, Lv X, Ge Y, et al. Age at menarche and risk of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: insights from the NHANES 2017-2020 and Mendelian randomization analyses. Exp Gerontol. 2025;204:112748.

81. Jaroenlapnopparat A, Charoenngam N, Ponvilawan B, Mariano M, Thongpiya J, Yingchoncharoen P. Menopause is associated with increased prevalence of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Menopause. 2023;30:348-54.

82. Kim SE, Min JS, Lee S, Lee DY, Choi D. Different effects of menopausal hormone therapy on non-alcoholic fatty liver disease based on the route of estrogen administration. Sci Rep. 2023;13:15461.

83. Dong J, Dennis KMJH, Venkatakrishnan R, Hodson L, Tomlinson JW. The impact of estrogen deficiency on liver metabolism: implications for hormone replacement therapy. Endocr Rev. 2025;46:790-809.

84. Maldonado SS, Grab J, Wang CW, Huddleston H, Cedars M, Sarkar M. Polycystic ovary syndrome is associated with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis in women of reproductive age. Hepatol Commun. 2022;6:2634-9.

85. Liu D, Gao X, Pan XF, et al. The hepato-ovarian axis: genetic evidence for a causal association between non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and polycystic ovary syndrome. BMC Med. 2023;21:62.

86. Wu Z, Liang G, Zhang Y, Li R. Risk factors for metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease in patients with polycystic ovary syndrome in east Asia: a review and meta-analysis. Endocr Pract. 2025;31:668-76.

87. El Jamaly H, Eslick GD, Weltman M. Systematic review with meta-analysis: non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and the association with pregnancy outcomes. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2022;28:52-66.

88. Froń A, Orczyk-Pawiłowicz M. Breastfeeding beyond six months: evidence of child health benefits. Nutrients. 2024;16:3891.

89. European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL), European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD), European Association for the Study of Obesity (EASO). EASL-EASD-EASO Clinical Practice Guidelines on the management of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD). J Hepatol. 2024;81:492-542.

90. Diaz LA, Arab JP, Idalsoaga F, et al. Updated recommendations for the management of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) by the Latin American working group. Ann Hepatol. 2025;30:101903.

91. Younossi ZM, Zelber-Sagi S, Lazarus JV, et al. Global consensus recommendations for metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease and steatohepatitis. Gastroenterology. 2025;169:1017-1032.e2.

92. Zargar AH, Bhansali A, Majumdar A, et al. Management of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD)-an expert consensus statement from Indian diabetologists’ perspective. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2025;27 Suppl 4 Suppl:3-20.

93. Jamalinia M, Saeian S, Nikkhoo N, Nazerian A, Lankarani KB. Sex and gender differences in MASLD: pathophysiological mechanisms, clinical implications, and future directions. Metab Target Organ Damage. 2025;5:60.

94. Vilar-Gomez E, Martinez-Perez Y, Calzadilla-Bertot L, et al. Weight loss through lifestyle modification significantly reduces features of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Gastroenterology. 2015;149. 367-78.e5; quiz e14-5.

95. Nascimbeni F, Ballestri S, Machado MV, et al. Clinical relevance of liver histopathology and different histological classifications of NASH in adults. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;12:351-67.

96. Dileo E, Saba F, Parasiliti-Caprino M, Rosso C, Bugianesi E. Impact of sexual dimorphism on therapy response in patients with metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease: from conventional and nutritional approaches to emerging therapies. Nutrients. 2025;17:477.

97. Bédard A, Corneau L, Lamarche B, Dodin S, Lemieux S. Sex-related differences in the effects of the mediterranean diet on glucose and insulin homeostasis. J Nutr Metab. 2014;2014:424130.

98. Leblanc V, Bégin C, Hudon AM, et al. Gender differences in the long-term effects of a nutritional intervention program promoting the Mediterranean diet: changes in dietary intakes, eating behaviors, anthropometric and metabolic variables. Nutr J. 2014;13:107.

99. D'Abbondanza M, Ministrini S, Pucci G, et al. Very low-carbohydrate ketogenic diet for the treatment of severe obesity and associated non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: the role of sex differences. Nutrients. 2020;12:2748.

100. Trouwborst I, Goossens GH, Astrup A, Saris WHM, Blaak EE. Sexual dimorphism in body weight loss, improvements in cardiometabolic risk factors and maintenance of beneficial effects 6 months after a low-calorie diet: results from the randomized controlled DiOGenes trial. Nutrients. 2021;13:1588.

101. Vitale M, Costabile G, Bergia RE, et al. The effects of Mediterranean diets with low or high glycemic index on plasma glucose and insulin profiles are different in adult men and women: data from MEDGI-Carb randomized clinical trial. Clin Nutr. 2023;42:2022-8.

102. Muscogiuri G, Verde L, Frias-Toral E, et al. Weight loss, changes in body composition and inflammatory status after a very low-energy ketogenic therapy (VLEKT): does gender matter? J Transl Med. 2024;22:949.

103. Zheng J, Zhou Z, Huang J, et al. Sugar rationing in the first 1000 days after conception and long-term risk of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease and major adverse liver outcomes: a natural experiment study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2025:S1542-3565(25)00923.

104. Yang Y, He L, Han S, et al. Sex differences in the efficacy of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists for weight reduction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Diabetes. 2025;17:e70063.

105. van Oortmerssen JAE, Mulder JWCM, van der Bijl MF, Mijnster RJM, Kavousi M, Roeters van Lennep JE. ; IMPRESS consortium. Lipid lowering therapy utilization and lipid goal attainment in women. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2025;27:29.

106. Weiskirchen R. Resmetirom and semaglutide in metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MASH): a comparative perspective. Explor Drug Sci. 2025;3:1008132.

107. Mahmoud M, Kawtharany H, Awali M, Mahmoud N, Mohamed I, Syn WK. The effects of testosterone replacement therapy in adult men with metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2025;16:e00787.

108. LiverTox: clinical and research information on drug-induced liver injury [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; 2012.

109. Bruno S, Maisonneuve P, Castellana P, et al. Incidence and risk factors for non-alcoholic steatohepatitis: prospective study of 5408 women enrolled in Italian tamoxifen chemoprevention trial. BMJ. 2005;330:932.

110. Braal CL, de Knegt RJ, Jager A, Koolen SLW, Mathijssen RHJ, Eechoute K. Tamoxifen use and potential effects on liver parenchyma: A long-term prospective transient elastographic evaluation. Hepatol Commun. 2022;6:2565-8.

111. Bessone F, Lucena MI, Roma MG, et al. Cyproterone acetate induces a wide spectrum of acute liver damage including corticosteroid-responsive hepatitis: report of 22 cases. Liver Int. 2016;36:302-10.

112. Yamada T, Tanaka S, Noda T, et al. Disproportionality analysis of flutamide- or bicalutamide-induced liver injury with and without steroids by using the Japanese Adverse Drug Event Report database. Int J Clin Pharm. 2025;47:128-35.

113. Nolan BJ, Cheung AS. Gender-affirming hormone therapy for transgender and gender-diverse adults in Australia. Intern Med J. 2024;54:1450-7.

114. Sluková D, Deischinger C, Just I, et al. The effects of gender-affirming hormone therapy on myocardial, hepatic, pancreatic lipid content, body fat distribution and other cardiometabolic risk factors: a magnetic resonance-based study in transgender individuals. J Clin Transl Endocrinol. 2025;39:100379.

115. Suvarna R, Shetty S, Pappachan JM. Efficacy and safety of Resmetirom, a selective thyroid hormone receptor-β agonist, in the treatment of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD): a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2024;14:19790.

116. Kantowski T, Schulze Zur Wiesch C, Aberle J, Lautenbach A. Obesity management: sex-specific considerations. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2024;309:1745-52.

117. Resmirom Leaflet folded. Available from: https://getzpharma.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/Resmirom-Leaflet.pdf. [Last accessed on 29 January 2026].

Cite This Article

How to Cite

Download Citation

Export Citation File:

Type of Import

Tips on Downloading Citation

Citation Manager File Format

Type of Import

Direct Import: When the Direct Import option is selected (the default state), a dialogue box will give you the option to Save or Open the downloaded citation data. Choosing Open will either launch your citation manager or give you a choice of applications with which to use the metadata. The Save option saves the file locally for later use.

Indirect Import: When the Indirect Import option is selected, the metadata is displayed and may be copied and pasted as needed.

About This Article

Special Topic

Copyright

Data & Comments

Data

Comments