Multiscale microstructure design for high-performance dielectric energy storage materials

Abstract

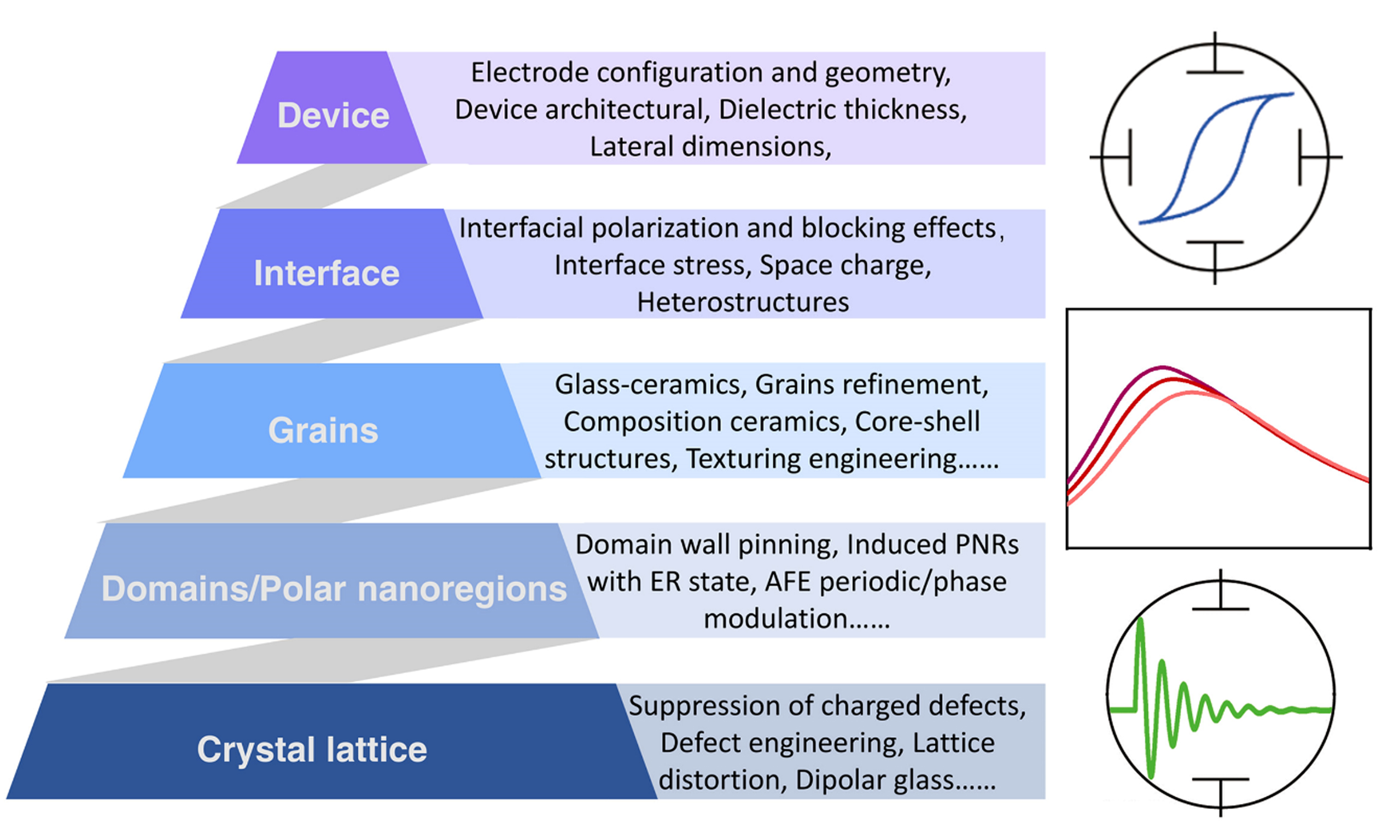

Dielectric materials are increasingly recognized as promising candidates for advanced energy storage and power amplification, particularly in dielectric capacitors that combine high power density with rapid charge-discharge capability and exceptional cycling stability. Special attention is given to the development of multilayer ceramic capacitors (MLCCs) for high-power pulsed systems, where the challenge lies in simultaneously achieving miniaturization and high energy density. This review highlights recent advances in dielectric materials, with particular emphasis on polarization engineering strategies that enhance energy and power densities through multiscale microstructural design, spanning devices, interfaces, grains, domains or nanoregions, and the lattice itself. Progress in material design is examined, including targeted doping, component solid solutions, high-entropy configurations, polarization mismatch, delayed polarization saturation, composite architectures, and texturing techniques, each evaluated for its role in improving dielectric performance. Special attention is devoted to solid-state dielectrics, which offer a unique combination of environmental compatibility and robust functional properties. The role of multiscale structural tailoring and processing innovations in optimizing dielectric responses is also explored. By integrating recent advances in polarization control and material design, this review outlines pathways toward next-generation dielectric energy storage systems, highlighting the importance of not only performance, but also scalability, reliability, and device integration.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

A broad spectrum of energy storage (ES) technologies has been developed, encompassing mechanical, chemical, electrochemical, and electrostatic approaches[1,2]. Among these, electrostatic energy storage, particularly in dielectric capacitors, has attracted increasing attention due to its inherently high power density (PD) and ultrafast charge-discharge capability[3-6]. These attributes position it as a compelling choice for integration into pulsed-power systems and advanced electronic circuits, where both ES and power amplification are critical.

The ES behavior of dielectric capacitors is fundamentally determined by the properties of their constituent dielectric materials, which include polymers, inorganic solids, and polymer-ceramic composites. The field has seen a surge of comprehensive reviews that contextualize historical developments, summarize current advancements, and outline future directions in dielectric materials research. For example, Wang et al. provided an in-depth analysis of electronic ceramics tailored for high-performance ES capacitors[7]; Yang et al. reviewed the progress, design principles, and persistent challenges of lead-free bulk ceramics[8]; Yang et al. synthesized recent developments in perovskite-structured lead-free dielectrics for capacitive applications[9]. Zhang et al. offered strategic insights into the rational design of perovskite dielectric materials, guiding the development of next-generation multilayer ceramic capacitors (MLCCs)[10]. In parallel, Qi et al. highlighted the critical role of local structure engineering in achieving high-performance lead-free ferroic dielectrics[11], while Dai et al. advocated combinatorial strategies for optimizing perovskite-based ferroelectric (FE) ceramics for ES applications[12]. In the polymer domain, Wei and Zhu critically examined intrinsic polymer dielectrics with high energy densities and low dielectric loss, identifying dipole glass polymers with engineered side- and main-chain architectures as promising candidates[13]. Complementarily, Yang et al. provided a systematic overview of polymer nanocomposites, detailing nanoscale strategies that have substantially enhanced the discharged energy density[14]. Collectively, these reviews serve as intellectual beacons, offering researchers a synthesized view of the evolution, challenges, and opportunities in the design and application of dielectric materials.

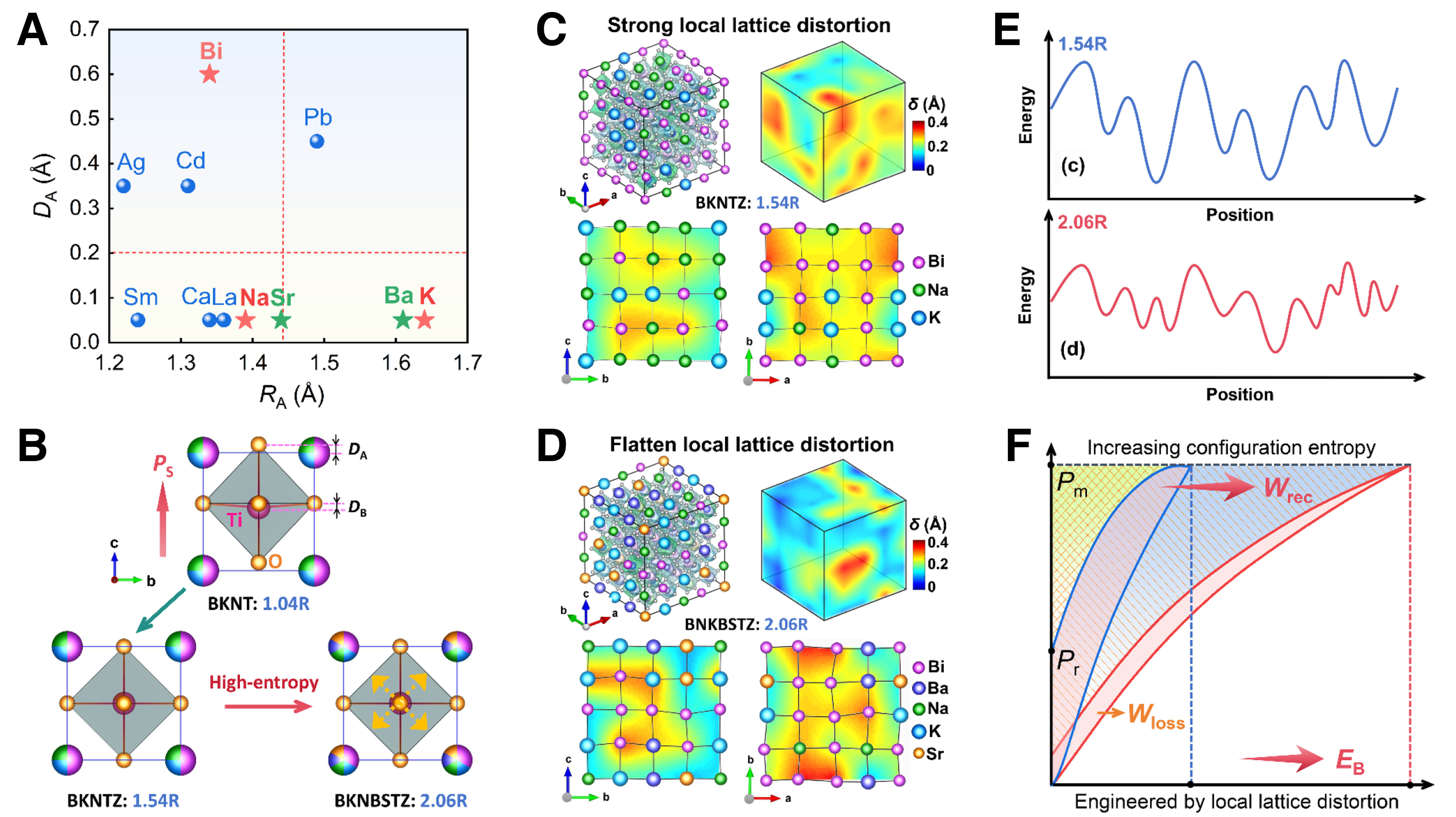

Recently, increasingly sophisticated microstructural and compositional design strategies have emerged, including grain-grain boundary engineering, nanocomposite ceramics, polar nanocluster modulation, and high-entropy approaches[4]. Given the pivotal role of multiscale microstructures in dictating material properties, it is crucial to recognize that dielectric capacitors store energy in the form of electric polarization, which is inherently dictated by hierarchical structural features across multiple length scales[11,15]. These span from electronic-scale orbital hybridization, lattice-level ion displacement, and g (PNRs) to meso- and macro-domain structures, extending up to grain-scale interfaces and even device-level architectural design.

Accordingly, this review proposes a phenomenological framework in which “microstructure-driven design” serves as a guiding principle for optimizing dielectric energy storage performance (ESP). We synthesize recent advances in the structural engineering of inorganic solid-state dielectrics, with a particular focus on bulk ceramics, and identify promising avenues for future innovation. Chemical modification, in combination with process optimization, remains the principal route for tailoring microstructure. Importantly, similar dopants can induce modifications across multiple length scales, and regulation at a given scale often produces distinct effects on polarization behavior. These observations underscore both the multifaceted roles of dopants and the intrinsic correlations between microstructures across different scales.

Microstructural strategies offer several transformative advantages. First, they enable precise tuning of critical material parameters through targeted modifications at specific length scales. Second, multiscale synergistic effects, arising from the integrated manipulation of macro-, meso-, and microstructures, can surpass the intrinsic performance limits of conventional materials. Third, these approaches facilitate the integration of multiple functionalities, advancing the frontier of intelligent dielectric materials. Finally, the microstructure-centric paradigm supports a closed-loop strategy that links the development of new materials, optimization of fabrication processes, and application-specific innovation. This framework is further empowered by advanced computational tools, including materials informatics, machine learning, AI-assisted discovery, and high-throughput simulations. Collectively, this review aims to illuminate a roadmap toward next-generation high-performance dielectric capacitors, grounded in the strategic manipulation of microstructure across all relevant scales.

Modes of electrical energy storage

ES systems serve as indispensable intermediaries, enabling temporal compression, spatial redistribution, and efficient regulation of electrical energy[1]. Currently, widely adopted ES technologies span a spectrum of mechanisms: chemical ES, exemplified by lithium-ion and flow batteries or hydrogen production via water electrolysis[16,17]; mechanical ES, including pumped hydro, flywheels, and compressed air[18]; and electromagnetic ES, where electricity is stored directly as electric fields (in dielectric capacitors), electrochemical double layers (supercapacitors), or persistent currents (superconducting magnetic ES)[19-21]. Each paradigm exhibits distinct performance profiles, differing in energy density, power density, charge-discharge rates, conversion efficiency, scalability, and compatibility with operational environments. These characteristics inherently tailor each technology to specific applications, highlighting the importance of context-driven selection in advanced ES systems.

Among these technologies, dielectric capacitors are uniquely distinguished by their purely physical storage mechanism[3]: energy is stored as electrostatic charge without involving intermediate chemical or mechanical conversions. This enables ultrahigh power density, sub-microsecond charge-discharge rates, and exceptional cycling endurance, positioning dielectric capacitors as prime candidates for high-repetition-rate pulsed power systems[7-9]. Dielectric capacitors also offer high voltage tolerance, low internal inductance, and robust power output, although they are limited by relatively low recoverable energy storage density (Wrec), which constrains their miniaturization potential.

Compared with power transistors and magnetic devices, ES MLCCs provide superior efficiency, lower losses, and higher volumetric specific power[9]. To meet the demands of pulsed power applications, where rapid delivery of large currents is critical, dielectric capacitors must combine high Wrec with high PD. ES MLCCs have emerged as a leading solution, offering compact form factors, fast discharge capabilities, scalable modular designs, and cost-efficient manufacturing. Their ability to operate reliably at high voltages while supporting rapid energy release renders them indispensable in defense technologies, electric propulsion systems, and advanced power electronics. It is noteworthy that, although ES MLCCs and conventional MLCCs (such as X7R and C0G devices) share similar fabrication processes, their applications differ fundamentally: ES MLCCs are designed for ultrahigh discharge currents and power densities under high operating fields, whereas conventional MLCCs primarily serve charge storage, filtering, and decoupling functions under lower electric fields[22].

As pulsed power systems continue to evolve toward higher output, faster cycling rates, and greater integration, the demand for capacitors with enhanced energy storage capacity, longer operational lifetimes, and superior reliability becomes increasingly pressing. The primary bottleneck lies in the development of dielectric materials capable of simultaneously delivering high Wrec and high PD. Achieving this balance is crucial for reducing the size and weight of MLCCs while accommodating increasingly complex and demanding functionalities. Overcoming this materials challenge is therefore essential to enabling the next generation of compact, high-performance pulsed energy technologies[4].

Principle of dielectric energy storage

Dielectric ES is fundamentally governed by the electric polarization of insulating materials under an external electric field. When a voltage is applied, bound charges within the dielectric are displaced or reoriented, giving rise to induced dipoles. This polarization process enables the accumulation of electrostatic energy within the material without involving chemical reactions or ion migration[7]. Consequently, dielectric capacitors exhibit ultrafast response times and superior cycling stability, making them particularly suitable for applications that demand rapid charge-discharge performance and long-term reliability.

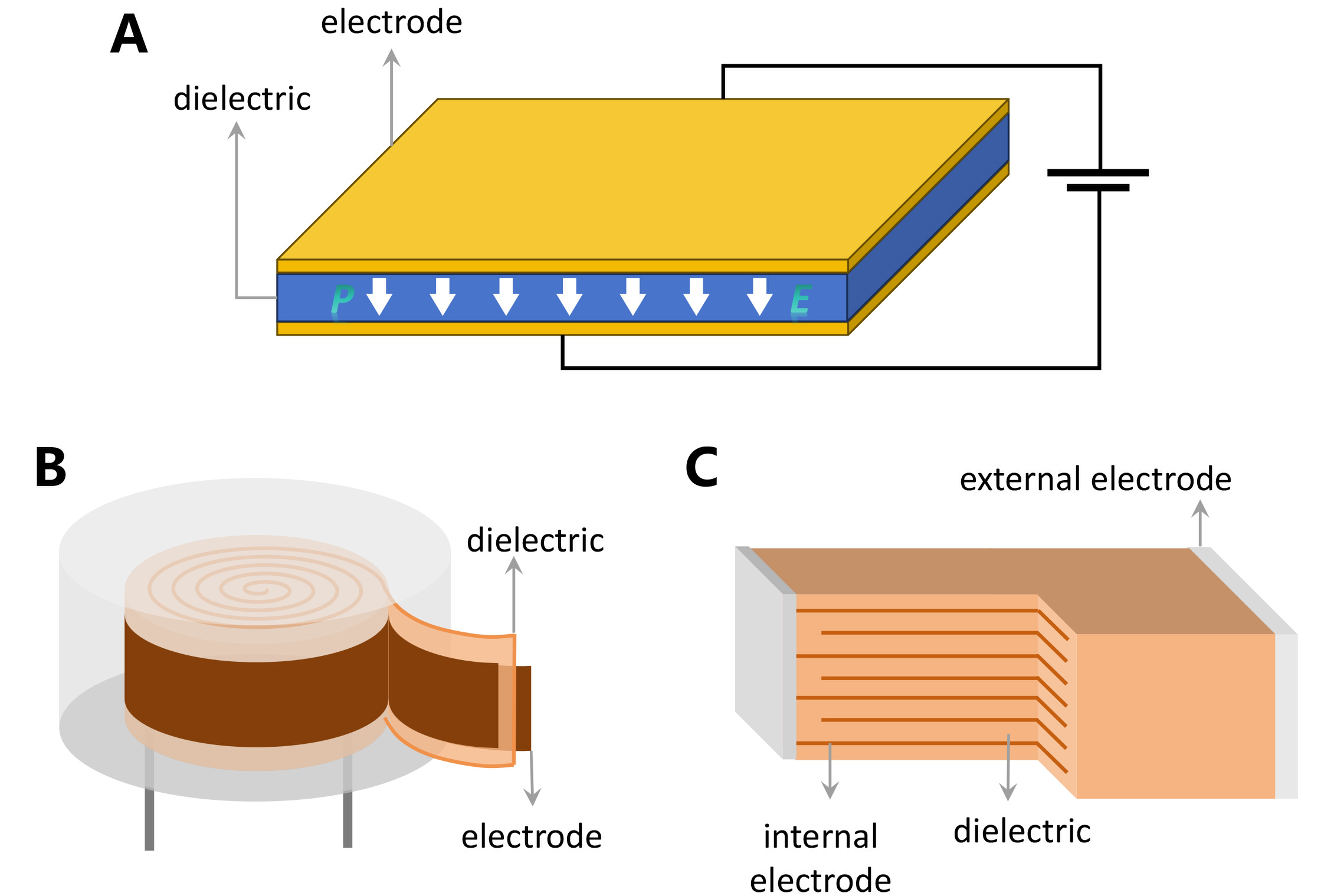

As schematically illustrated in Figure 1A, the most basic implementation of dielectric energy storage is the parallel-plate capacitor, in which two conductive electrodes enclose a dielectric layer. The intrinsic properties of the dielectric, including permittivity, polarization response, and dielectric breakdown strength (BDS), critically determine the capacitor’s charge-storage capability.

Figure 1. Illustration of three common dielectric capacitor configurations: (A) Parallel-plate capacitor, the conceptual model for ES via dielectric polarization; (B) Rolled-film capacitor, widely used in power electronics, offering flexibility and scalability through thin-film windings; (C) MLCC, composed of alternating layers of ceramic dielectric and internal electrodes, enabling high volumetric efficiency, large capacitance values, and excellent frequency response. ES: Energy storage; MLCC: multilayer ceramic capacitor.

Among these architectures, MLCCs have become the workhorse of modern high-power and high-frequency applications. Advances in material engineering and microstructural control enable the precise tuning of dielectric properties, optimizing both ESP and operational reliability. Key dielectric properties-including high relative permittivity (εr), low dielectric loss, and elevated breakdown field-govern not only the stored energy density and charge-discharge efficiency but also the long-term stability of these devices under demanding operational conditions[23].

Categories of dielectric materials

In principle, any good electrical insulator can function as a dielectric medium for ES, including both inorganic non-metallic materials and organic polymers. However, to achieve high Wrec, different strategies are adopted depending on the material system. As shown in Figure 1B, polymer-based dielectrics leverage their intrinsic flexibility and ease of processing. These materials are typically fabricated into ultrathin films and rolled into compact structures to minimize thickness and maximize capacitance per unit volume[14]. In contrast, inorganic dielectric materials, particularly ceramics with intrinsically high εr, are often processed into MLCCs to enhance volumetric Wrec by minimizing device size while maintaining high capacitance (see Figure 1C).

The εr of a material originates from three primary polarization mechanisms: electronic polarization, ionic displacement polarization, and dipolar orientation polarization[24]. Dipolar orientation, driven by the reconfiguration of permanent dipoles in response to an external electric field, significantly contributes to dielectric permittivity, with values often ranging from 103 to 104. As a result, most high-permittivity dielectrics studied and applied in modern capacitor technologies are FE-based materials[25].

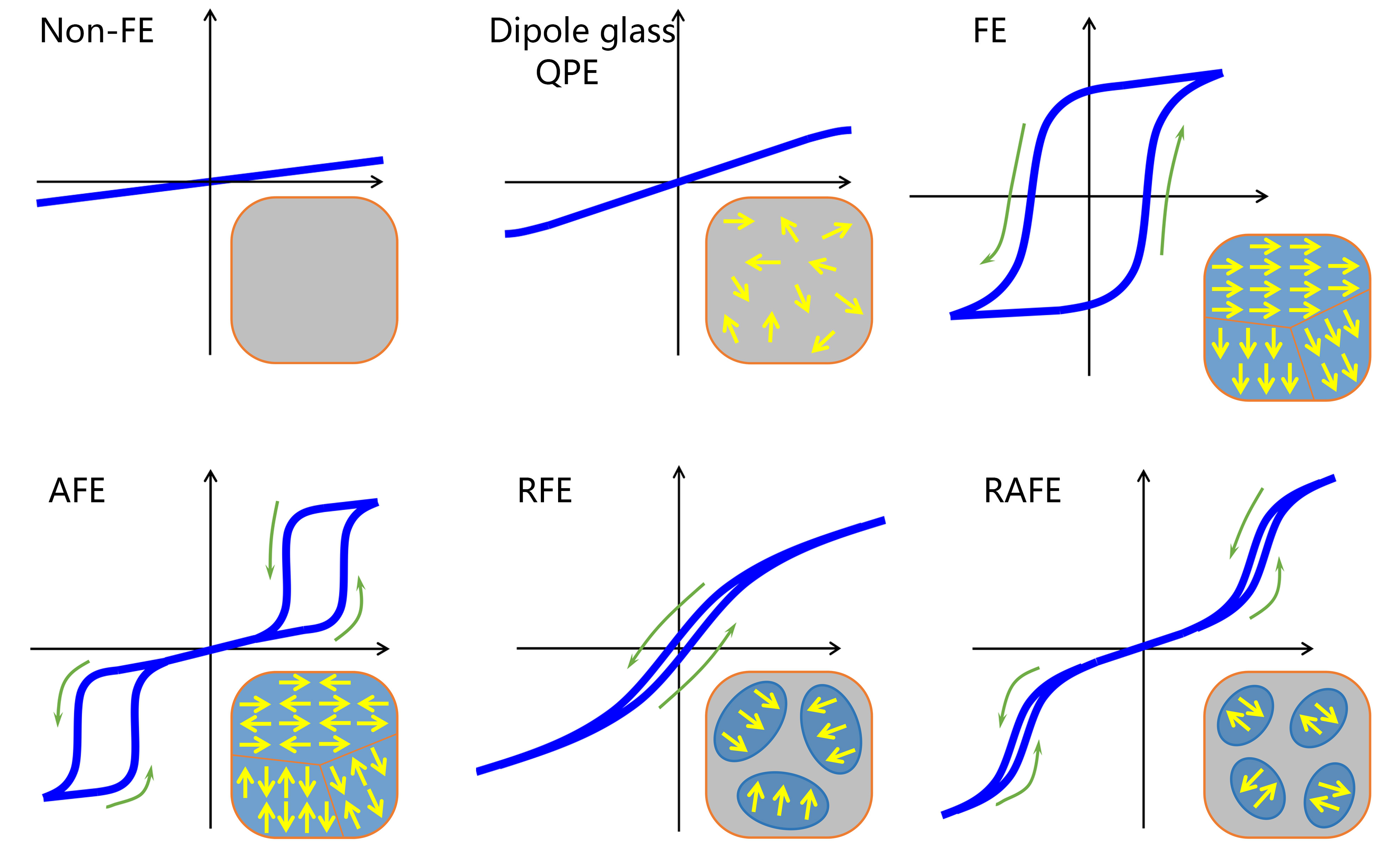

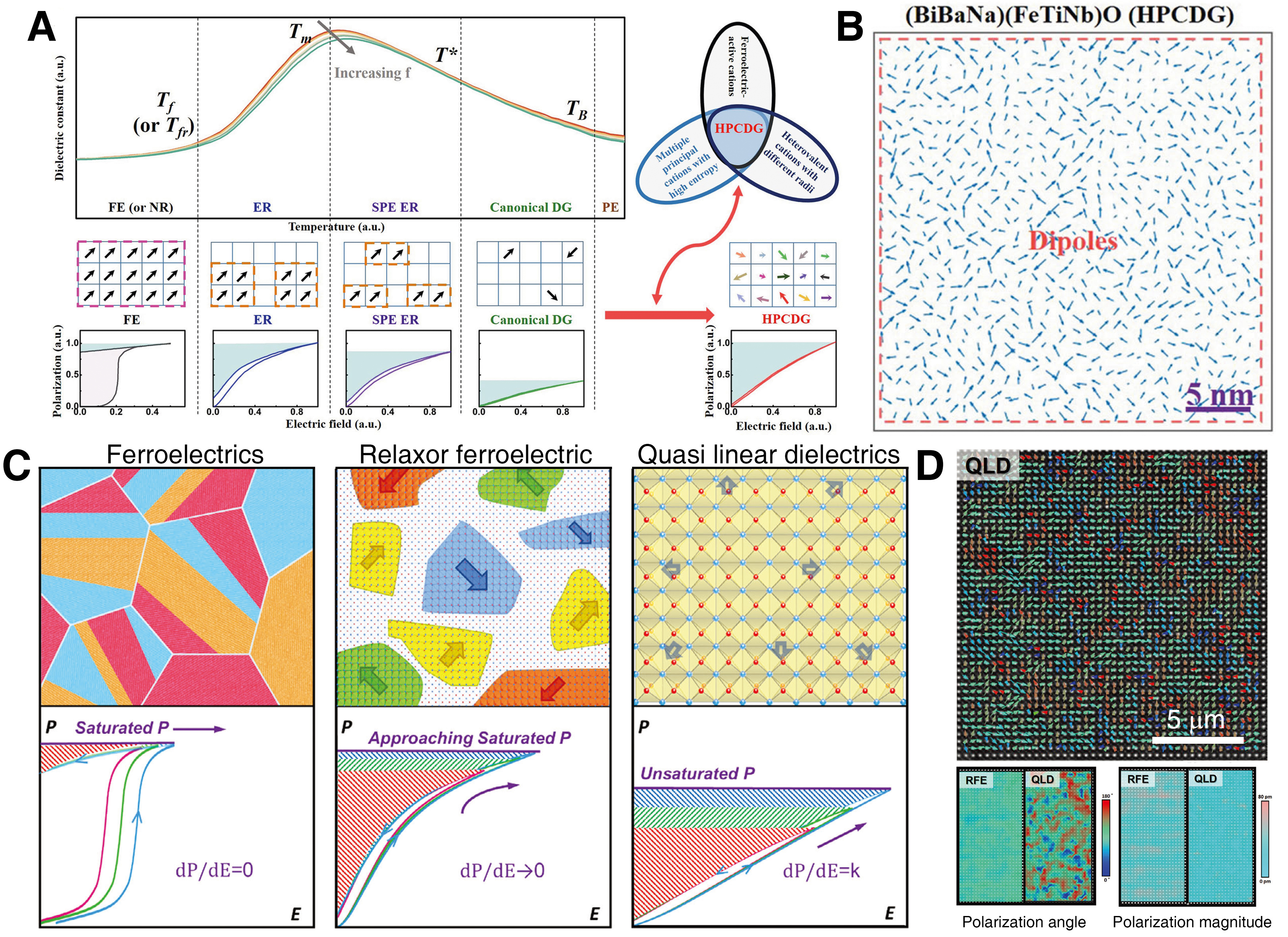

FE-related materials can be broadly categorized based on their microscopic dipole configurations and macroscopic polarization behaviors, as illustrated in Figure 2[26,27]. These include FE, antiferroelectric (AFE), relaxor ferroelectric (RFE), relaxor antiferroelectric (RAFE), and dipole glass or quantum paraelectric (QPE) materials. In FE materials, adjacent dipoles within the crystal lattice align to produce uniform spontaneous polarization, forming long-range ordered domains. These domains are energetically stable and separated by domain walls, which act as energy barriers to dipole reorientation. Consequently, FEs exhibit pronounced hysteresis in their polarization-electric field (P-E) hysteresis loops, marked by remanent polarization (Pr) and coercive fields, reflecting their strong nonlinear response and memory effects[26].

Figure 2. Schematic representation of characteristic dipolar structures and corresponding P-E hysteresis loops across different material classes. AEF: Antiferroelectric; RFE: relaxor ferroelectric; RAFE: relaxor antiferroelectric; FE: ferroelectric; QPE: quantum paraelectric.

AFEs, on the other hand, feature antiparallel alignment of dipoles within adjacent unit cells, resulting in zero net polarization under zero field[28]. When subjected to a sufficiently high electric field, AFEs can undergo a field-induced AFE-to-FE phase transition, during which the antiparallel dipoles reorient into a parallel configuration[29]. This unique behavior gives rise to a double P-E hysteresis loop, making them promising candidates for high-Wrec capacitor applications.

RFEs possess short-range correlated dipoles, often forming PNRs[30,31]. These PNRs fluctuate dynamically, contributing to strong dielectric dispersion and pronounced nonlinearity[32]. Unlike conventional FEs, RFEs exhibit slim P-E loops with high maximum polarization and minimal hysteresis, enabling excellent ES efficiency (η) under high electric fields.

Lastly, QPEs are systems with weak dipole-dipole interactions, where quantum fluctuations suppress the formation of long-range FE order, even at low temperatures[33]. These materials display minimal dielectric nonlinearity, negligible hysteresis, and relatively low permittivity, making them less favorable for energy storage but highly valuable for investigations of fundamental quantum phenomena[34,35].

In summary, selecting an appropriate dielectric material system requires careful consideration of the complex interplay between microscopic dipole behavior and the emergent macroscopic dielectric properties. Advancing the understanding and precise engineering of these polarization mechanisms is essential for realizing high-performance capacitors with superior ES capabilities.

DIELECTRIC ENERGY STORAGE PERFORMANCE

Characterization methodologies

Dielectric capacitors, particularly those intended for pulsed power and advanced power electronics, demand rigorous evaluation of several key metrics: Wrec, η, and PD. These parameters collectively determine the practical utility of a dielectric material in high-PD applications. Two primary approaches are employed to quantify ESP: the indirect (quasi-static) method and the direct (dynamic) method[9]. The indirect approach relies on P-E hysteresis loops acquired via a FE workstation. By integrating the area enclosed within the P-E loop, one can derive the Wrec and η. This method offers a convenient and rapid means of evaluating dielectric behavior, particularly useful in high-throughput material screening and comparative studies. In contrast, the direct method captures the dynamic response of a dielectric capacitor under real working conditions, employing a series resistor-inductor-capacitor (RLC) discharge circuit. This setup enables time-resolved acquisition of voltage and current (I) signals via an oscilloscope during capacitor discharge. The Wrec, discharge duration, current density, and PD are derived through time integration of the electrical output, thereby reflecting the actual performance of the dielectric material under pulse operation. Compared to the indirect method, the direct discharge technique provides a more faithful representation of operational characteristics, especially under high-speed, high-voltage conditions. As such, it serves as an indispensable tool in the design and validation of advanced dielectric ES systems.

Key determinants

As derived from the integral-based formalism of Wrec, the dielectric ES capability of a material is fundamentally governed by two pivotal factors: its polarization response and its BDS. Conceptually, enhancements in maximal polarization (Pmax) and in the ability of a material to sustain high electric fields without dielectric failure are directly correlated with improvements in Wrec and η. These two aspects, while inherently interconnected, originate from distinct scientific and engineering domains.

From a materials engineering perspective, strategies to elevate BDS primarily focus on processing optimization and microstructural refinement. Techniques such as densification, grain-size control, and defect management are frequently employed, often combined with modest compositional tuning to fine-tune intrinsic properties[7,8]. In contrast, the modulation of polarization behavior is predominantly dictated by compositional design and chemical tailoring, encompassing approaches such as isovalent or aliovalent doping, controlled structural heterogeneity, and precise manipulation of phase boundaries[26]. These methods, firmly rooted in materials science principles, provide effective levers for tuning dielectric performance. Consequently, the realization of synergistic improvements in dielectric ESP requires a dual strategy: simultaneously enhancing BDS and optimizing the polarization response.

Crucially, both polarization and breakdown behavior are intricately coupled to the multiscale microstructure of the dielectric. The spatial distribution, morphology, and nature of grains, grain boundaries, porosity, and defect chemistry act as critical mediators that govern field-dependent polarization dynamics and influence the statistical likelihood of dielectric breakdown events. This underscores a central insight: multiscale microstructural design and engineering represent the most powerful route for advancing the ESP of dielectric ceramics.

a. Breakdown strength

Among all parameters influencing dielectric capacitor performance, BDS stands out as the most critical for high-power pulse applications. In particular, for MLCCs operating under high-voltage and high-charge conditions, BDS defines the safe operational field and thereby dictates device reliability and lifetime. Breakdown phenomena in dielectrics can be broadly categorized as intrinsic, thermal, partial discharge-induced, or hybrid in nature[36]. For bulk ceramics, the measured BDS reflects not only intrinsic physical parameters (such as bandgap, electronic conductivity, dielectric loss, and thermal conductivity) but also extrinsic factors, including sample geometry (thickness and electrode area), microstructural features (density, grain size, and defect topology), and external testing conditions (frequency, waveform, thermal management, and atmosphere).

Advances in processing and chemical modification provide the principal routes to enhancing BDS. In practice, ultra-dense ceramics fabricated by hot pressing or spark plasma sintering generally outperform those produced by conventional sintering[37-40]. Statistical effects further favor thinner ceramic layers, which typically exhibit higher BDS than thicker counterparts, partly owing to the reduced probability of failure from defects or thermal accumulation[9]. Chemical modification offers an additional lever: appropriate dopants can broaden the bandgap, reduce the density of mobile charge carriers, and raise the activation energy for defect migration. Additives may also serve as sintering aids or grain-growth inhibitors, promoting denser and more uniform microstructures. These improvements, however, must be balanced, since excessive doping can trigger secondary phase formation or elevate dielectric loss[41].

Although BDS is a critical parameter, its increase alone does not necessarily translate into proportional gains in ESP. While a higher BDS permits stronger applied fields and potentially higher polarization, it is the field dependence of the polarization response that ultimately governs recoverable energy. Once polarization approaches saturation, additional increases in field yield diminishing returns in Pmax while simultaneously heightening the risk of breakdown. Thus, the notion that maximizing BDS alone guarantees optimal ESP is an oversimplification. Instead, coupling high BDS with a field-responsive yet controllably saturating polarization behavior represents a more effective paradigm for the design of next-generation dielectric capacitors.

b. Polarization response

The polarization response of dielectric materials is central to their ESP. As a fundamental electrostatic phenomenon, it governs key metrics including Wrec, η, and PD by bridging intrinsic dielectric behavior with extrinsic factors such as BDS. This response arises from the synergistic interplay of multiscale structural features under an applied electric field, ranging from atomic dipole arrangements to mesoscale domain configurations. The practical viability of a dielectric for ES is therefore dictated by the nature of its polarization behavior.

Three descriptors are commonly employed to characterize polarization dynamics: hysteresis, Pmax, and the polarization pathway. Comparative evaluation of these parameters provides critical insight into material-specific storage capabilities. For instance, pronounced hysteresis is typically associated with substantial energy dissipation during field cycling, rendering conventional FEs and AFEs less efficient for ES. In contrast, materials with high Pmax, particularly RFEs, can deliver elevated Wrec and are thus positioned as strong candidates for advanced dielectric capacitors. Beyond these parameters, the polarization pathway itself plays a decisive role. Field-induced phase transitions, particularly those producing abrupt polarization jumps, can markedly enhance Wrec even when BDS and Pmax remain constant. Such behavior is exemplified by RAFE systems, which surpass conventional RFEs due to their distinctive transition kinetics.

These polarization characteristics are intimately linked to the material’s polar microstructure, encompassing dipolar configurations with varying degrees of order, correlation lengths, and responsiveness. While spontaneous polarization is an intrinsic lattice property, the macroscopic response is strongly modulated by hierarchical structural features, including nanodomains, defect complexes, and grain boundaries. Consequently, microstructural design has become a central strategy for tailoring polarization behavior to enhance ESP. This strategy must be system-specific. For linear dielectrics (LDs), characterized by low permittivity and negligible hysteresis, efforts primarily focus on maximizing Pmax. For FEs, which offer high intrinsic spontaneous polarization but suffer from large hysteresis losses, the key challenge lies in suppressing hysteresis while retaining high polarization.

Importantly, hysteresis, Pmax, and polarization trajectory are inherently interdependent; optimization of one parameter often perturbs the others, leading to unavoidable trade-offs. Furthermore, polarization dynamics are closely coupled with dielectric breakdown behavior, and the two often compete. Thus, optimizing dielectric ESP requires a multiscale co-engineering strategy that balances these competing factors. The overarching objective is to sustain a high Pmax, suppress hysteresis, delay polarization saturation, and simultaneously enhance BDS, all of which are indispensable for achieving next-generation high-Wrec dielectric capacitors.

MULTISCALE MICROSTRUCTURE AND ITS DETERMINISTIC ROLE IN DIELECTRIC ES

Despite the intrinsic properties of dielectrics being decisive for their fundamental BDS and polarization capability, the observable macroscopic ESP is, in practice, governed by the complex interplay of structural features across multiple length scales. A quintessential example is the significant discrepancy, often spanning one to two orders of magnitude, between the theoretical breakdown field and the experimentally measured values in bulk dielectric ceramics. This divergence arises because intrinsic BDS defines the ideal dielectric failure limit in a defect-free, perfectly homogeneous material, whereas real materials undergo premature breakdown driven by localized discharges, thermal runaway, and aging-related structural degradation, all of which are fundamentally controlled by the microstructure. From a materials design perspective, it is therefore both rational and imperative to prioritize microstructural optimization to enhance dielectric ESP. Through targeted structural engineering across scales, extrinsic failure mechanisms can be suppressed and polarization dynamics finely tuned to achieve superior functionality.

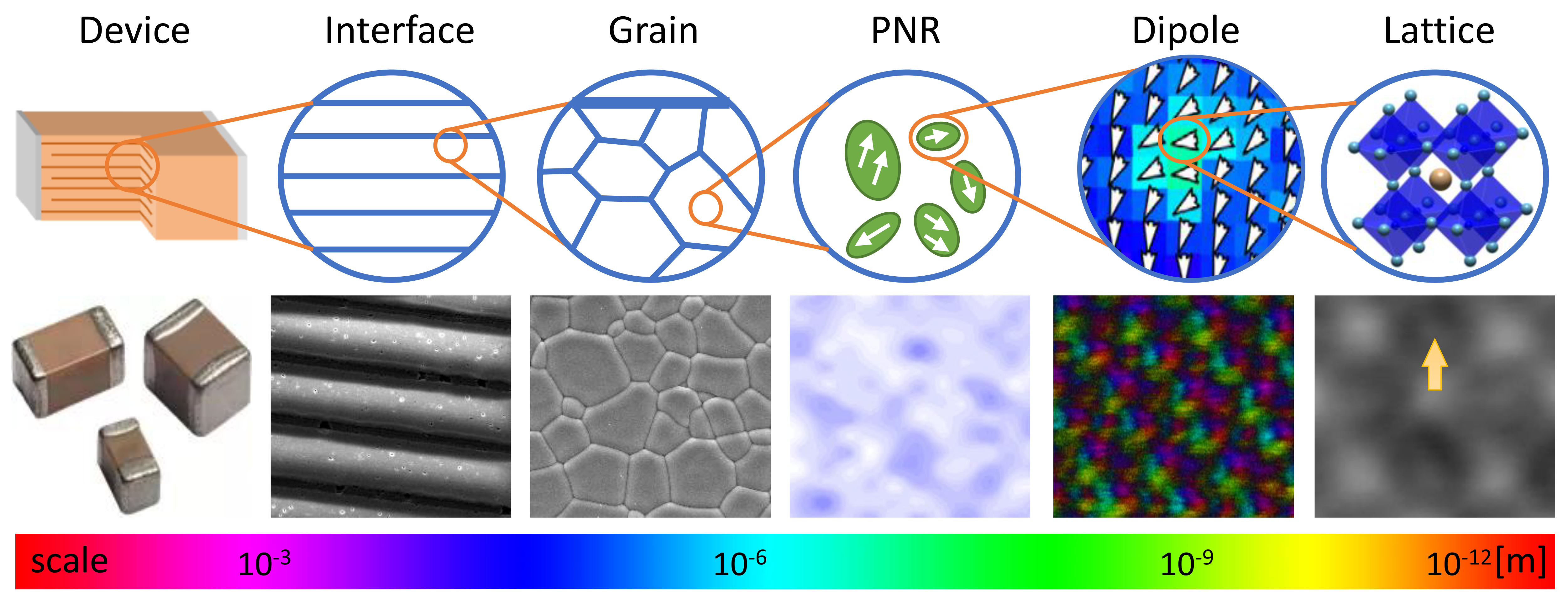

Structural hierarchy: from macro to atomic scale

As illustrated schematically in Figure 3, the microstructure of bulk dielectric ceramics exhibits a hierarchical architecture spanning six interrelated spatial scales:

Figure 3. The microstructures at different scales that determine or influence the ESP of MLCC. ESP: Energy storage performance; MLCC: multilayer ceramic capacitor.

• Device scale: Includes macroscopic parameters such as sample dimensions, thickness, electrode configuration, and boundary constraints.

• Interface scale: Encompasses junctions between ceramic dielectrics and metallic electrodes, as well as internal interfaces in compositional or gradient multilayer structures.

• Grain scale: Covers the distribution, orientation, and boundary character of ceramic grains, together with associated porosity and intergranular defects of comparable dimensions.

• Domain/microdomain/PNR scale: Describes the spatial organization and dynamic behavior of polar structures, ranging from micrometer-scale FE domains to nanoscale regions of correlated dipoles.

• Dipolar scale: Refers to the collective interactions and spatial correlations among local dipole moments that give rise to complex polarization patterns and responses.

• Lattice scale: Encompasses atomic-level features such as spontaneous ionic displacements, local distortions, and point defects within the unit cell.

Within this multiscale framework, the material’s polarization response and dielectric breakdown characteristics arise not from a single dominant length scale, but from the cooperative influence of structural heterogeneities across all scales. Spontaneous polarization, for instance, is rooted in orbital hybridization, particularly involving Bi3+ and Pb2+ in RFEs[9]. Its magnitude Pmax, field dependence, and hysteretic behavior are jointly shaped by orientation potential barriers at the lattice scale, by spatial correlations and dynamic fluctuations of dipoles at the mesoscopic scale, and by the role of grain boundaries and defects at the grain scale. At the device scale, interfacial conditions and internal stress distributions further regulate the observable polarization, completing the cascade of scale-dependent interactions that define macroscopic behavior.

This multiscale coupling is particularly prominent in RFEs, where the presence of chemical disorder and nanoscale compositional fluctuations gives rise to a distribution of PNRs embedded within a heterogeneous matrix. The macroscopic dielectric response and ESP in such systems represent a statistical average of a broad ensemble of local polarization states and dynamic reconfiguration pathways. Consequently, tuning the microstructure across various scales, from atomic substitutions and defect engineering to mesoscale texturing and interfacial tailoring, provides a practical and scientifically well-founded strategy to modulate dielectric performance.

Therefore, a rational design strategy must aim to suppress high-loss mechanisms (e.g., excessive orientational polarization), optimize the response time of relevant polarization types to match the application bandwidths, and homogenize the microstructure to minimize local field concentrations. This coordinated approach enables a balance between high permittivity, low loss, and enhanced BDS, thereby achieving a comprehensive enhancement of ESP. Fundamentally, this optimization paradigm represents a targeted, multiscale polarization engineering strategy that integrates spatial structuring and dynamic response design.

Characterization techniques across microstructural scales

To enable precise microstructural engineering, an arsenal of complementary characterization techniques is required, each tailored to the relevant length scale and structural features of interest. Below is a concise taxonomy of key tools employed in multiscale microstructural analysis:

(a) Device/Macro scale: Visual inspection and optical microscopy suffice for observing overall surface morphology and cracking behavior. Advanced X-ray computed tomography (X-CT) and ultrasound imaging provide non-destructive, three-dimensional evaluation of internal structural defects[42].

(b) Interface scale: High-resolution scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM) are used to assess interfacial roughness, topology, and defect distribution[43,44]. Ultrasound-based imaging can also reveal subsurface inhomogeneities[45].

(c) Grain scale: SEM combined with electron backscatter diffraction (EBSD) and energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) delivers multimodal data on grain size, boundary character, orientation, and elemental distribution[46]. Optical microscopy (OM), including polarized light microscopy, is effective for analyzing large-grain ceramics and detecting residual stress. X-ray diffraction (XRD) enables phase identification, lattice strain analysis, and estimation of average grain size. Micro-CT permits three-dimensional defect mapping at the microscale[47].

(d) Domain/PNR scale: Field-emission SEM and transmission electron microscopy (TEM) resolve fine-scale domain configurations[48]. Piezoelectric force microscopy (PFM) is particularly powerful for mapping local polarization amplitude and phase, and for revealing domain wall dynamics and reversible switching behavior under external bias fields. PFM also provides insights into temperature- and stress-dependent domain evolution[49].

(e) Atomic/Dipolar scale: Advanced scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM), high-resolution TEM (HR-TEM), and electron energy loss spectroscopy (EELS) offer atomic-resolution imaging of lattice distortions, point defects, and bonding environments[50,51]. For quantitative analysis of ionic displacement vectors, local polarization, and electrostatic field gradients, aberration-corrected STEM equipped with high-angle annular dark field (HAADF), differential phase contrast (DPC), and integrated bright field (IBF) is essential[52-54].Atom probe tomography (APT) enables three-dimensional compositional mapping at near-atomic resolution, particularly for analyzing segregation at grain boundaries or interfacial phases[55]. To capture real-time microstructural evolution under functional stimuli such as electric fields, temperature, or mechanical stress, in-situ TEM platforms are increasingly employed, enabling direct observation of field-driven domain wall motion, lattice distortion, and defect dynamics at unprecedented resolution[56,57].

MICROSTRUCTURAL DESIGN STRATEGIES

Achieving breakthroughs in dielectric ESP, whether by enhancing the breakdown electric field or optimizing polarization responses, ultimately relies on the rational design of material microstructure across multiple length scales[58]. These include not only compositional engineering and additive modulation, but also innovative processing, fabrication, and sintering methodologies. This section presents a comprehensive discussion of microstructural design strategies at various scales, highlighting their underlying mechanisms, comparative advantages, and the remaining challenges, along with avenues for future optimization.

Macroscale design considerations

At the macroscopic level, microstructural design encompasses the geometric parameters of dielectric devices and bulk ceramics, such as sample thickness, lateral dimensions, and electrode configuration, which exert a significant impact on dielectric breakdown and ES behavior. One of the most widely used and effective strategies for enhancing Wrec is the intentional reduction of sample thickness and electrode area. This approach is grounded in statistical and thermal principles: in systems where defects are randomly distributed, smaller electrode areas lower the likelihood of activating critical flaws under high fields. Thinner samples also improve heat dissipation, thereby mitigating localized thermal accumulation. Accordingly, bulk ceramics prepared via conventional solid-state sintering often exhibit markedly lower BDS than those fabricated through tape casting or the viscous polymer process. Even mechanical thinning via surface grinding and polishing has been adopted to boost the breakdown field and Wrec.

It is important to note that while macroscale strategies can effectively enhance measured performance metrics, they do not yield intrinsic improvements in the material itself. Although such extrinsic enhancements can be valuable for performance demonstrations, they offer limited contribution to advancing the fundamental understanding of materials. This distinction underscores the urgent need for standardized testing protocols in dielectric ES research.

Moreover, the use of ultrathin dielectric layers and reduced electrode dimensions may introduce significant edge effects and parasitic capacitance, which can artificially inflate Wrec values[59]. Ding et al. carried out comprehensive experimental and theoretical investigations, revealing that the presence of material non-idealities, particularly in low-permittivity dielectrics such as A2O3 and SrTiO3 (ST), leads to significant discrepancies in the measured electrical properties, as shown in Figure 4. These deviations become especially pronounced when asymmetric or small-area electrodes are employed, underscoring the critical influence of electrode geometry and dielectric quality on the accuracy of property characterization[59]. Their work proposed a calibration method for eliminating parasitic capacitance artifacts and recommended standardized configurations to enhance data reliability, offering a pivotal step toward methodological rigor in the field.

Figure 4. Finite element method simulations of parallel-plate capacitors with varying geometric configurations. (A) Schematic of the parallel-plate capacitor model; (B) Simulated electric field distributions along L1 (surface) and L2 (center) in the x-direction across the cross-section of Al2O3 in air. Light red, gray, and blue regions indicate the sample area under electrode coverage, the area outside electrode coverage, and the surrounding air, respectively; (C) Comparison of relative permittivity ratios (εr,FEM/εr,0: lines; εr,exp/εr,0: dots) for Al2O3 capacitors with different d/t ratios. Error bars denote standard deviations; (D) Electric field distributions along the x-direction at the center of the Al2O3 cross-section in air for different bottom electrode widths (dbot), with dbot = 3 mm and dielectric thickness t = 0.5 mm; (E) Dependence of εr,FEM/εr,0 on dbot. Here, εr,0 is the intrinsic dielectric constant, εr,FEM is the FEM-calculated dielectric constant, and εr,exp is the experimentally measured value. This figure is quoted with permission from Ding et al.[59]. FEM: Finite element method.

Beyond size effects, electrode geometry and architecture also play a critical role in governing dielectric breakdown behavior and Wrec in MLCCs[60]. Cai et al.[60] developed a phase-field electromechanical model and demonstrated that MLCCs with extended electrode margin lengths exhibit significantly enhanced BDS. Specifically, employing a margin length of 400 μm enabled a Wrec of 7.8 J/cm3 under an applied electric field of 790 kV/cm. This finding highlights a promising and resource-efficient strategy for optimizing ES performance at the device scale.

In parallel, novel architectural strategies such as interlaminar strain engineering have emerged as transformative tools to regulate domain structure and decouple the traditional trade-off between high polarization and low hysteresis. Yang et al. engineered a multilayer dielectric stack comprising compositionally distinct AFE ceramics, as shown in Figure 5, thereby creating a heterogeneous strain distribution capable of manipulating polarization dynamics[61]. This configuration achieved a record-high Wrec of 22.0 J/cm3 together with an ultrahigh η of 96.1%. These results establish a new benchmark, emphasizing the pivotal role of macroscale heterostructure engineering in pushing the performance limits of next-generation ES devices.

Figure 5. Interlaminar strain engineering strategy for enhanced ESP in MLCCs. (A) Schematic illustration of the engineered MLCC (S4) featuring a periodic heterogeneous layer structure; (B) Comparison of domain structures and P-E loops for S1, S2, and S3 under high electric fields. Samples S1 and S3, characterized by small domains, exhibit slim P-E loops with minimal hysteresis and negligible Pr, albeit with low maximum polarization. This figure is quoted with permission from Yang et al.[61]. ESP: Energy storage performance; MLCC: multilayer ceramic capacitor; AEF: antiferroelectric; FE: ferroelectric.

Interface scale engineering

In ideal bulk dielectric ceramics, the microstructure is typically treated as homogeneous and isotropic, rendering interfacial effects relatively minor compared with those in composite materials[62] and heteroepitaxial thin films[63-65]. However, this assumption does not universally hold, particularly for multiphase composite ceramics and compositionally graded bulk systems, where interface phenomena play a significant role in modulating dielectric behavior. In layered composite dielectrics, for example, the intrinsic disparity in electrical conductivity and dielectric permittivity between constituent phases can give rise to pronounced interfacial polarization and blocking effects. These effects may either enhance or compromise overall material performance: while interfacial polarization can strengthen the macroscopic polarization response, the accumulation of space charges at interfaces often elevates the risk of dielectric breakdown. Accordingly, interface engineering must be carefully tailored to the specific composition and performance objectives of the dielectric system.

Recent studies underscore the effectiveness of interfacial modulation. Hu et al. introduced a rational design strategy in AFE composites by pairing high-breakdown-field Pb0.94La0.04(Zr0.99-xSnxTi0.01)O3 (PLZST) with high-η Pb0.8925Ba0.04La0.045(Zr0.65Sn0.3Ti0.05)O3 (PBLZST), leveraging Sn content modulation to minimize interfacial dielectric mismatch and thereby suppress detrimental interfacial polarization[66]. Similarly, Yang et al. implemented a multilayer AFE ceramic structure based on the synergistic coupling of interfacial polarization and blocking effects in (Pb0.9Ba0.04La0.04)(Zr0.65Sn0.3Ti0.05)O3/(Pb0.95Ca0.02La0.02)(Zr0.93Sn0.05Ti0.02)O3 ceramics[67]. The engineered interface enabled simultaneous optimization of Pmax and BDS, resulting in a Wrec of 9.4 J/cm3. Notably, even without explicit interface optimization, processing methods that introduce compositional and structural heterogeneity, such as tape casting, roll compaction, lamination, and co-sintering, can inherently induce interface-scale modifications that significantly influence material performance. These mesoscale heterostructures are often designed to synergize the advantageous features of each constituent phase, mitigate their individual limitations, or balance mutually exclusive properties[68].

For example, Yang et al. employed a multilayer configuration combining RFE (Bi0.5Na0.5)TiO3 (BNT)-based and RAFE PLZST-based ceramics, as shown in Figure 6A, thereby optimizing dielectric properties through deliberate mesoscale assembly[69]. In another example [Figure 6B], Liu et al. addressed the intrinsic trade-off between polarization and BDS via a laminated composite strategy, constructing a bilayer structure with a high-polarization AFE and a high-breakdown AFE, achieving a record-high Wrec of 13.9 J/cm3 and η of 89.9%[70].

Figure 6. Interface-scale engineering of heterogeneous composite ceramics for enhanced dielectric and ESP. (A) Schematic of a multilayer sandwich structure combining RFE and RAFE components. The accompanying plot shows the εr as a function of applied DC electric field, with microstructural insets illustrating the evolution of domain structures under different field strengths. This figure is quoted with permission from Yang et al.[69]; (B) Schematic of the fabrication process for laminated composite ceramics using a tape casting method. This figure is quoted with permission from Liu et al.[70]. PLSZTS:(Pb0.875La0.05Sr0.05)(Zr0.695Ti0.005Sn0.3)O3; ESP: energy storage performance; PZ: PbZrO3; DC: direct current; PZS: Pb(Zr0.88Sn0.12)O3; RFE: relaxor ferroelectric; RAFE: relaxor antiferroelectric; AEF: antiferroelectric.

Furthermore, interface-level design has emerged as a critical strategy in developing lead-free dielectric ES materials[71-75]. Huan et al. successfully designed layered-structured lead-free (K0.5Na0.5)NbO3 (KNN)-based ceramics that exhibit both high BDS and large polarization[71]. More recently, a multilayer sandwich-structured composite attained an ultrahigh Wrec of 9.05 J/cm3 and a near-ideal η of 97% under

Beyond composite systems, interfaces are inherently ubiquitous in single-phase polycrystalline ceramics due to intrinsic microstructural heterogeneities such as grain boundaries and pores. When the thickness of the grain boundary is negligible, it can be regarded simply as the interface between adjacent crystalline grains. In this context, grain boundary engineering has emerged as a critical strategy for enhancing ESP, a topic further elaborated in the section on grain-scale structural design. Conversely, when the grain boundary phase is sufficiently thick, it often behaves as an amorphous or non-crystalline region, introducing new dielectric interfaces that profoundly influence the material’s electrical response, a prime example demonstrated by Li et al.[76]. This improvement was attributed to the effective suppression of space charge accumulation at the amorphous-crystalline interface, a mechanism pivotal for realizing high recoverable ESP. Similarly, Cao et al. emphasized the central role of interfacial polarization in governing ESP parameters, including grain size, bandgap, and relaxor behavior[77]. Their work established interfacial polarization as a key factor in optimizing dielectric performance.

Further engineering by Cao et al. involved tuning the activation energy differential between grains and grain boundaries, as shown in Figure 7, effectively restricting interfacial polarization and achieving a remarkable breakdown strength (Eb) of 640 kV/cm and Wrec of 15.1 J/cm3 in 0.62(0.94BNT-0.06BaTiO3)-0.38(Ca0.7La0.2)TiO3 (BNT-BT-CLT) ceramics[78].

Figure 7. Interface polarization and local electric field modulation in brick-and-mortar ceramic structures. (A) Schematic of a brick-and-mortar ceramic architecture, illustrating structural heterogeneity; (B) Maxwell-Wagner two-layer condenser model describing interface polarization and its influence on local electric fields. (C and D) Simulated electric field distributions across the sample as a function of potential difference (Δ) under two scenarios: (C) when the resistance of layer 1 greatly exceeds that of layer 2 (R1 ≫ R2), and (D) when the resistances are comparable (R1 ≈ R2). This figure is quoted with permission from Cao et al.[78].

Compared with bulk ceramics, interfacial design at the nanometer scale is more commonly implemented in thin-film dielectrics via multilayer heterostructures[79]. A variety of fabrication techniques, including chemical deposition[80], epitaxy[81], sol-gel synthesis[82], and radio frequency magnetron sputtering[83], have been employed to construct nanostructured dielectric films with finely tailored interfaces and exceptional electrical properties. For example, Nguyen et al. engineered multilayer films integrating paraelectric-like (Ba0.6Sr0.4)TiO3 (BST) with RFE Ba(Zr0.4Ti0.6)O3 (BZT) on Si substrates buffered with ST, achieving a record Wrec of 165.6 J/cm3 at an unprecedented breakdown field of 7.5 MV/cm[84].

In another approach, Zhai et al. addressed the common limitation of low BDS in Ag(Nb,Ta)O3-based films via interface engineering[85]. By introducing a BaTiO3 (BT) layer and using an n-type LaNiO3 buffer, a vertical n-p-n heterojunction was formed, elevating the energy barrier for carrier injection, reducing leakage currents, and significantly enhancing Wrec to 62.3 J/cm3. A similar concept was extended to double-heterojunction capacitors combining FE, dead-layer (DL), and superparaelectric (SPE) constituents. In the Bi0.9Sm0.1Fe0.9Co0.05Zn0.05O3/Al0.9Ga0.1O3/Ba0.985Na0.015Ti0.95Ni0.05O3 (BSFCZ/AGO/BNTN) system, interface and composition design preserved a high polarization of 55 μC/cm2 while suppressing remnant polarization, resulting in a giant Wrec of 132 J/cm3 and an η of 84% at an Eb of 5,500 kV/cm[80].

An emerging area of research focuses on engineering the interface between dielectric materials and electrodes, typically involving metal/inorganic non-metal junctions. This interface can give rise to unique physical phenomena not present within the internal dielectric heterostructures. For example, Silva et al. achieved efficient ES by inserting a thin HfO2:Al2O3 (HAO) interlayer between 0.5Ba(Zr0.2Ti0.8)O3-0.5(Ba0.7Ca0.3)TiO3 (BCZT) ceramics and gold electrodes[65]. The induced depolarization field improved linearity and reduced energy loss. Similarly, Chen et al. demonstrated that inserting an ultrathin Ca0.2Zr0.8O1.8 (CSZ) artificial “dead-layer” between Ba0.3Sr0.7Zr0.18Ti0.82O3 (BSZT) films and Au electrodes significantly suppressed Schottky emission through the formation of a 3.92 eV injection barrier[86]. This strategy effectively enhanced thermal stability and dielectric strength under high fields.

Additionally, Sun et al. investigated the influence of electrode-film interfaces by controlling the stacking sequence in BT/SiO2-BaZr0.2Ti0.8O3 multilayers[87,88]. Structures starting with the SiO2-BaZr0.2Ti0.8O3 layer consistently exhibited higher Eb and Wrec, attributed to the formation of Schottky barriers via 2Ti3+-

Figure 8. Schottky barrier formation at the dielectric-substrate interface enables electric field redistribution and enhanced BDS. (A) Cross-sectional STEM images of BCZTOD/BCZT//(1P) and BCZT/BCZTOD//(1P) heterostructures, accompanied by corresponding lattice ball-and-stick models; (B) Energy band diagram of the BCZT/BCZTOD//(1P) structure under forward bias, depicting the metal-semiconductor-dielectric configuration and the formation of a Schottky barrier at the interface. (C) Schematic illustration of Wrec in different types of P-E loops. High Wrec is achieved by suppressing the negative-side FE contribution, enabling improved ESP. BCZT: Ba0.7Ca0.3Zr0.2Ti0.8O3; BCZTOD: oxygen-deficient BCZT. This figure is quoted with permission from Sun et al.[88]. BDS: Dielectric breakdown strength; STEM: scanning transmission electron microscopy; ESP: energy storage performance; FE: ferroelectric; BCZT: 0.5Ba(Zr0.2Ti0.8)O3-0.5(Ba0.7Ca0.3)TiO3; NSTO: Nb-doped SrTiO3.

Grain-scale microstructural engineering

The grain-scale microstructure is among the most critical determinants of dielectric behavior and ESP in FE ceramics. Engineering strategies at this length scale are essential for enhancing polarization dynamics and improving dielectric BDS, both of which play a critical role in determining Wrec and η. As shown, Wrec is proportional to Eb2 and is also influenced by the effective polarization difference (Pmax-Pr), with Eb representing the dielectric BDS. The microstructural features at the grain scale, including grain size, boundary integrity, local electric field distribution, and space charge accumulation, decisively influence both Eb and polarization behavior.

One of the most straightforward yet effective approaches to boosting Eb in dielectric ceramics is grain refinement in tandem with densification, which reduces internal voids and defect concentrations. However, the properties of the grain-boundary phase, including its insulating behavior, thermal conductivity, and ability to accumulate or dissipate space charges, also exert significant secondary effects on polarization stability and dielectric losses. Furthermore, compositional tuning at the grain level offers an additional degree of freedom, enabling modulation of relaxation behavior and the associated polarization mechanisms. Therefore, the grain-scale microstructure design strategies summarized in this subsection include grains, grain boundaries, and corresponding compositional changes, as shown in Figure 9.

Figure 9. Grain-scale microstructural engineering strategies for optimizing dielectric ESP. (A) Promotion of microcrystal precipitation to form glass-ceramic structures; (B) Grain refinement and densification to enhance dielectric uniformity; (C) Formation of composite ceramics comprising grains with distinct compositions or crystal structures; (D) Construction of core-shell architectures via controlled elemental diffusion or compositional segregation; (E) Grain boundary modification through low-melting-point dopants or chemical coating of pre-synthesized powders; (F) Development of oriented grains using textured ceramic processing. ESP: Energy storage performance.

Glass ceramics

Glass ceramics and dipole glasses are typically regarded as linear dielectric materials, characterized by their non-switchable polarization behavior and linear dielectric response under applied electric fields[8]. Nevertheless, a fundamental drawback of these materials lies in their relatively low εr, which, despite their high Eb, limits the Pmax and ultimately constrains their Wrec. To overcome these intrinsic limitations, microstructural engineering strategies have been increasingly explored.

Among these, compositional tailoring and process optimization remain the most effective and widely adopted approaches[7], both aimed at introducing or forming a strong polar phase. Controlled heat treatment and crystallization protocols play a crucial role in modulating the microstructure. Compared with amorphous phases, crystalline domains typically exhibit higher dielectric permittivity and polarization capacity. Facilitating the controlled formation of such crystalline phases within a glassy matrix can effectively enhance the overall dielectric performance while retaining the thermal and chemical stability advantages of the glass-ceramic system.

The glass materials intended for dielectric ES are often referred to as dielectric glass ceramics or microcrystalline glasses, emphasizing the coexistence of crystalline and glassy phases[22]. Liu et al. comprehensively summarized recent advances in high-Wrec FE glass-ceramics, analyzing the critical factors influencing their dielectric performance and outlining prospective directions[89]. A direct microstructural design strategy for improving both the dielectric permittivity and inducible polarization in such materials lies in promoting controlled crystallization. One of the most effective routes to enhance crystallization and, consequently, the dielectric constant is to increase the crystallization temperature[90-93]. For example, in the BaO-Na2O-Nb2O5-SiO2-TiO2-ZrO2 glass-ceramic system, the dielectric constant increased markedly from 36.8 at a crystallization temperature of 750 °C to 103.5 at 1,050 °C, primarily due to the formation of NN and Ba2NaNb5O15 crystalline phases[92]. In addition to thermal treatments, compositional engineering via the introduction of suitable dopants has proven highly effective in promoting crystallization and enhancing the dielectric response.

Rare-earth oxides or other functional additives are commonly employed for this purpose[94-97]. In Gd2O3-doped BaO-K2O-Nb2O5-SiO2 glass ceramics, the increasing Gd2O3 content leads to the gradual emergence of crystalline phases such as Ba2KNb5O15, BaNb2O6, and K3NbO4, which contribute to both higher dielectric permittivity and enhanced Pmax under the same electric field[98]. While tungsten bronze and other structures are effective, perovskite-type FE crystals typically offer even higher dielectric constants due to their intrinsic lattice polarizability. Thus, compositional control strategies aimed at promoting perovskite-phase crystallization represent a promising avenue for further dielectric enhancement[99].

However, it is undeniable that microstructural strategies designed to promote crystallization, while improving the dielectric constant of glass ceramics, inevitably sacrifice other critical advantages inherent to linear dielectrics, such as dielectric stability, polarization linearity, low dielectric loss, and high Wrec[100]. For linear dielectric materials, a clear trade-off exists between polarization capability and BDS. When employing this structural tuning strategy, careful consideration must be given to the trade-offs between various performance parameters based on the specific application requirements. Overall, linear dielectric ceramics, with their superior thermal/frequency stability, remain highly promising for applications in ultra-high-voltage pulsed circuits. For example, Shang et al. designed the “amorphous-disordered-ordered” microstructure in BT-based glass ceramics by the ingenious strategy of defect formation modulation, as shown in Figure 10, resulting in a high Wrec of 12.04 J/cm3 and a superb PD of 973 MW/cm3[101]. This representative work demonstrates a feasible route to obtain glass ceramics with an outstanding ESP and proves the enormous potential of glass ceramics in high and pulsed power applications.

Figure 10. Enhanced ESP in BT-based glass ceramics via defect formation modulation leading to an “amorphous-disordered-ordered” microstructure. (A) Schematic illustrating defect formation during crystallization without and with electric field assistance; (B) High-resolution TEM image of BTAS glass ceramic showing morphology and lattice fringes; insets display the selected area electron diffraction pattern and grain size distribution histogram; (C) P-E loops of BTAS glass ceramics measured at 10 Hz. The BTAS composition corresponds to glass ceramics crystallized under a 3 kV/cm electric field. This figure is quoted with permission from Shang et al.[101]. ESP: Energy storage performance; TEM: transmission electron microscopy; BT: BaTiO3; BTAS: BaO-TiO2-Al2O3-SiO2.

Grain refinement and density enhancement

The grain size, porosity, and phase uniformity of dielectric ceramic materials are key factors influencing their dielectric breakdown field; then, the dielectric and polarization responses are also affected based on size effects and clamping effects. A large porosity is highly detrimental to the breakdown field. Under the requirement of high Wrec, refining the grain size has been widely proven to improve BDS and is one of the most common strategies for grain structure design, which has been extensively validated across various systems[102-106] as shown in Figure 11.

Figure 11. Grain refinement and densification enhance dielectric BDS. (A) Evolution of electric field and development of breakdown paths under a constant field of 320 kV/cm for 0.1-CS and 0.25-HPS ceramics. The 0.1-CS sample is a 0.9Bi0.5Na0.5TiO3-0.1K0.5Na0.5NbO3 ceramic prepared by conventional sintering, while the 0.25-HPS sample is a 0.75Bi0.5Na0.5TiO3-0.25K0.5Na0.5NbO3 ceramic prepared by hot-press sintering. This figure is quoted with permission from Deng et al.[103]; (B) Simulated distributions of dielectric constant, electric potential, and local electric field in ceramic macrostructures before and after amorphous phase filling. This figure is quoted with permission from Zhang et al.[106]. BDS: Dielectric breakdown strength.

Refining the grain structure can reduce defects and pores, thereby mitigating localized electric potential concentration. The increased grain boundary density and number act as insulating barriers, hindering the development of electrical treeing and reducing the probability of dielectric breakdown[106]. Additionally, the fine-grained structure, through high-density grain boundaries, suppresses the migration of thermally activated charge carriers, reducing leakage current and Joule heat accumulation. This not only enhances the material’s thermal stability under high electric fields but also prevents thermal breakdown. The grain size directly influences the size and distribution of FE domains, with smaller grains significantly reducing domain size. Due to size effects, the FE macrodomains transition into nanosized domains or polar microregions. As a result, the ferroelectricity weakens or may even disappear, significantly lowering the coercive field, remnant polarization, hysteresis, and energy loss.

Moreover, grain refinement may affect polarization behavior. For example, in RFEs, small grains can enhance the local random field, suppressing remnant polarization, and improving η. Wang et al. investigated the impact of grain size and grain boundaries on the ESP of polycrystalline FEs using a phase-field model[105]. As shown in Figure 12, their findings indicate that the depolarization field at the grain boundary induces vortex domains when the grain size is reduced or when the grain boundary thickness increases to a certain extent, leading to narrow P-E loops. The influence of these grain microstructural features on breakdown characteristics and polarization behavior can be utilized to improve dielectric ESP.

Figure 12. Influence of grain size on polarization behavior and ESP in polycrystalline FEs. (A) Domain structures of polycrystalline models at remnant polarization state with varying grain sizes; (B) P-E loops, (C) ESP, and (D) Pr as a function of average grain size. This figure is quoted with permission from Wang et al.[105]. ESP: Energy storage performance; FE: ferroelectric.

However, it is important to note that smaller grain sizes are not always better; there may be an optimal size range. Excessively small grains may lead to an excessive number of grain boundaries, which can reduce the dielectric constant or maximum induced polarization, or cause difficulties in preparation and densification. According to Wang’s research, further decreasing the grain size or increasing the grain boundary thickness results in a decrease in Wrec due to a concurrent reduction in both remnant and saturation polarization[105]. Therefore, it is crucial to select the optimal size range based on the material system[107].

Grain refinement and densification are fundamental to improving the dielectric ESP of ceramic materials. The underlying mechanism involves enhancing BDS and optimizing polarization characteristics by fine-tuning the microstructure. This approach has proven to be a generally applicable strategy for boosting dielectric ES capacity. Several material preparation methods and chemical processing techniques can effectively achieve this goal. These processes typically encompass ceramic powder fabrication, sintering techniques, and the use of chemical additives.

Reducing the initial powder size, enhancing sintering activity, and inhibiting grain boundary migration during sintering are all effective strategies for controlling grain growth. Applying physical pressure during sintering facilitates particle rearrangement, mass transfer, and plastic flow, thereby promoting densification and lowering sintering barriers. A common approach is hot pressing, in which uniaxial pressure (typically 10-50 MPa) is applied during high-temperature sintering, accelerating densification and limiting grain growth. Rapid sintering techniques also contribute to both densification and grain refinement. One such method is spark plasma sintering (SPS), which generates high temperatures almost instantaneously through pulsed direct current while applying pressure, achieving rapid sintering and densification and suppressing excessive grain growth. Similar techniques include microwave sintering and flash sintering. In addition, chemical methods such as sol-gel processing, hydrothermal or solvothermal synthesis, and co-precipitation enable the preparation of homogeneous, nanometer-sized precursor powders, which, after sintering, yield fine-grained ceramics.

Sintering can also be optimized through two-step processes[108] or the addition of grain growth inhibitors to enhance density and reduce grain size. For instance, introducing second-phase materials like MgO, SiO2, or Y2O3, or doping with elements such as La3+ and Nb5+, can pin grain boundaries or reduce their migration, effectively suppressing grain growth. By combining physical and chemical methods and optimizing sintering parameters, it is possible to achieve coordinated control over both grain refinement (< 1 μm) and high density (> 98%), significantly improving the dielectric ESP.

When designing high-performance dielectric ceramics for ES, grain refinement is often coupled with other modification techniques. For example, chemical composition adjustments, doping, and multiscale structural designs (such as multilayer structures, core-shell configurations, or composite ceramics) are employed to further enhance performance. Liu et al. demonstrated exceptionally high BDS and ESP in lead-free BT-based RFE using a combined strategy of composition modification, viscous polymer processing, and liquid-phase sintering[109]. Composition modification disrupted long-range FE order, while liquid-phase sintering enabled low-temperature densification and grain refinement, as shown in Figure 13A. Viscous polymer processing (VPP) allowed for thinner single-layer ceramic samples, illustrating an effective collaborative optimization strategy that could serve as a paradigm for the development of new dielectric ES ceramics.

Figure 13. Grain refinement and densification significantly enhance ESP in dielectric ceramics. (A) Ultrahigh dielectric BDS and superior ESP achieved in BT-based RFE ceramics through combined composition modification, viscous polymer processing, and liquid-phase sintering. This figure is quoted with permission from Liu et al.[109]; (B) Schematic illustrating strategies to realize outstanding ESP in Bi0.5Na0.5TiO3-based RFE ceramics. This figure is quoted with permission from Zhu et al.[110]; (C) Grain refinement and pore reduction via two-step firing in 0.6BNT-0.21BT-0.19BiScO3 ceramics, resulting in doubled BDS and enhanced ESP. This figure is quoted with permission from Xu et al.[112]. ESP: Energy storage performance; RFE: relaxor ferroelectric; BDS: dielectric breakdown strength; BNT: (Bi0.5Na0.5)TiO3; BT: BaTiO3

For RFE materials, particularly those with rapidly saturating polarization, simply refining the grain structure to improve the breakdown field provides limited enhancement in ES. It is more effective to combine this with strategies designed to delay saturation polarization for significant performance improvements[110-112], as illustrated in Figure 13B and C. Li et al. developed a composite dielectric with an intragranular segregation structure, achieving excellent ESP by delaying saturation polarization[113]. This approach demonstrates how strategic modifications to polarization dynamics can significantly boost the ES capabilities of FE materials.

The FE properties of FE materials are highly dependent on grain size, with various dielectric properties exhibiting a pronounced size effect. Numerous studies have explored these effects and have established that the dielectric response, as well as other electrical characteristics, can be significantly influenced by grain size[114-118]. Tan et al. have found that the grain size effect is universal and nearly independent of the sintering method and the starting powder[117]. Zhang et al. studied the grain size dependence of domain wall activity in a lead-free (Ba,Ca)(Zr,Ti)O3 system and demonstrated that the dielectric properties of polycrystalline FEs are influenced by the grain size, particularly through the dynamics of domain walls[119]. Their research found that the highest dielectric permittivity occurs at intermediate grain sizes, which facilitate easier and faster domain wall dynamics, coupled with moderate lattice distortion.

Interestingly, the size effect can also be exploited as a strategy for suppressing ferroelectricity. By reducing polarization hysteresis, this approach can enhance dielectric ESP[120]. It is widely applied in the production of MLCCs. Typically, BT is a FE material, exhibiting high polarization hysteresis and energy loss. However, low-voltage, high-dielectric MLCCs commonly employ nanoscale BT grains. These ceramics exhibit relaxation-like behavior rather than the typical FE response. Additionally, the incorporation of rare-earth ions into grain boundaries further improves performance by promoting the formation of multiphase ceramics and core-shell structures. This strategy extends the temperature range and stability of the dielectric constant, enabling the production of MLCC materials with standardized temperature stability parameters such as X7R, X8R, and X9R[22,121-124].

Grain size and defect engineering have a significant impact on the dielectric properties of BT-based ceramics and the temperature coefficient of capacitance in MLCCs[125-127]. For BT ceramics, grain refinement helps suppress tetragonal lattice distortion and ferroelectricity, thereby reducing polarization hysteresis and broadening the dielectric peak. Although the grain size effect is widely applied in low-field applications of BT-based MLCC devices, where a high dielectric constant is leveraged for functions, such as charge storage and filtering, the primary demand for dielectric ES materials focuses on exploiting high polarization responses for power amplification and pulsed discharge. In these materials, the most crucial structural requirement for industrialization remains densification and grain refinement. For dielectric ES ceramics, ensuring finely tuned grains is essential to achieve optimal performance, particularly in applications that rely on high polarization for ES and rapid energy release.

Composite ceramics

The design of composite FE ceramics at the grain scale aims not merely to alter the intrinsic physical or chemical properties of the matrix phase through dopant modification, but rather to harness the distinct advantages of multiple end-member phases through engineered composite microstructures. Broadly defined, a variety of structural configurations fall under the category of composite ceramics. These include multilayer architectures, ceramics with heterogeneous, additive-induced secondary phase precipitations, co-sintered systems comprising mixed compositional constituents, and materials exhibiting core-shell architectures formed via the diffusion of additives into grain lattices during processing. This section specifically focuses on 0-0 type composite ceramics, wherein compositional heterogeneity is introduced at the grain level.

The 0-0 composite paradigm refers to systems in which discrete grains of two different compositions are distributed throughout the ceramic matrix[66]. These grains may share the same crystal structure but differ in chemical composition, or they may possess fundamentally distinct crystallographic symmetries. For instance, Hu et al. developed a 0-0 type composite by co-sintering two Pb-based RFE compounds with complementary functional characteristics. The high-breakdown-field Pb0.94La0.04(Zr0.99-xSnxTi0.01)O3 was combined with the high-efficiency Pb0.8925Ba0.04La0.045(Zr0.65Sn0.3Ti0.05)O3 to construct a composite with markedly improved ESP. The resulting ceramic exhibited a high Wrec of approximately 7.15 J/cm3 and an η of about 90.5% under an electric field of 345 kV/cm[66].

More commonly, high-performance composite systems are achieved by integrating materials with inherently distinct crystal structures and polarization mechanisms. These include combinations of perovskite phases with bismuth-layered, tungsten-bronze, or pyrochlore-type phases. For example, Wu et al. developed a ST-based diphase composite by introducing the bismuth-layered BaBi2Nb2O9 into the perovskite relaxor matrix of Sr0.6(Na0.5Bi0.5)0.4TiO3[128], as shown in Figure 14A. This strategy yielded a ceramic capable of delivering a Wrec of approximately 3.6 J/cm3 and an outstanding η of 94.3% under moderate electric fields. Similarly, Wang et al. proposed a heterogeneous combination strategy involving embedding a high Eb plate-like pyrochlore phase in a high-polarization perovskite phase[129], as shown in Figure 14B. The embedded plate-like pyrochlore enhances the breakdown field strength and facilitates the dynamic polarization response. Meanwhile, the strong spin-orbit coupling effect of the 5d electrons helps maintain the high polarization value of the perovskite. Other notable examples include pseudo-cubic BT matrix ceramics with Ba4MgTi11O27 as the secondary phase[130] (as shown in Figure 14C), as well as composites of BNT (a classic perovskite FE) with the pyrochlore-structured Sm2Ti2O7[131]. These systems collectively demonstrate that the deliberate design of grain-scale phase coexistence, especially between end-members exhibiting contrasting dielectric and polarization characteristics, provides an effective strategy for enhancing both Wrec and operational η in lead-based and lead-free dielectric ceramics.

Figure 14. Enhanced ESP through grain-scale composite ceramic design. (A) Incorporation of bismuth layer-structured BaBi2Nb2O2 into perovskite Sr0.6(Na0.5Bi0.5)0.4TiO3 ceramic via traditional solid-state synthesis to improve overall ESP. This figure is quoted with permission from Wu et al.[128]; (B) Embedding high-breakdown-strength plate-like pyrochlore phase within high-polarization perovskite matrix to boost ES in BNT-based ceramics. This figure is quoted with permission from Wang et al.[129]; (C) Superior ESP in BT-based RFE ceramics with reconstructed microstructure featuring elongated rod-shaped and polygonal perovskite grains. This figure is quoted with permission from Yin et al.[130]. ESP: Energy storage performance; BNT: (Bi0.5Na0.5)TiO3; ES: energy storage; RFE: relaxor ferroelectric; BT: BaTiO3; BMT: Bi(Mg1/2Ti1/2)O3.

In addition to conventional FE or relaxor components, high-melting-point oxides capable of forming distinct secondary phases, such as HfO2[132,133] and ZrO2[134,135], have emerged as promising candidates for engineering advanced composite FE ceramics. These oxides can be selectively introduced to create heterostructures with tailored local electric fields and optimized dielectric behaviors. For instance, Lu et al. developed a self-assembled metadielectric nanostructure by embedding HfO2 nanophases within a BaHf0.17Ti0.83O3 RFE matrix, as shown in Figure 15A. The inclusion of HfO2 contributed to a significant enhancement in dielectric BDS, improved RFE characteristics, and a reduction in conduction losses. As a result, the fabricated thin-film capacitors achieved an exceptional Wrec of up to 85 J/cm3, with an η surpassing 81%[132]. In a similar approach, Shen et al. incorporated HfO2 into 0.75BNT-0.24NN-0.01ST RFE ceramics to construct heterogeneous composites. Here, HfO2 particles were predominantly located along grain boundaries, acting as physical barriers that effectively suppressed the formation of localized electric branches while preserving high saturation polarization. This structural design strategy ensured a marked improvement in ESP and reliability under high fields[133]. As shown in Figure 15B, isolated ZrO2 secondary phases embedded in the perovskite matrix not only enhance the fracture toughness of the ceramics but also improve electrical insulation and broaden the bandgap, resulting in excellent stability, reliability, and superior charge-discharge performance.

Figure 15. Enhanced ESP via self-assembled metadielectric nanostructures and phase toughening in RFE ceramics. (A) Self-assembled BaHf0.17Ti0.83O3-xHfO2 metadielectric nanostructure: schematic of structural evolution, breakdown phase transitions, and corresponding P-E hysteresis loops under breakdown conditions. This figure is quoted with permission from Lu et al.[132]; (B) Schematic illustrating improved ESP in ZrO2-toughened Ba0.55Sr0.45TiO3-Bi0.5Na0.5TiO3-SrZrO3 RFE ceramics due to enhanced BDS following ZrO2 phase incorporation. The studied composition is 0.4 Ba0.55Sr0.45TiO3-0.4 Bi0.5Na0.5TiO3-0.2SrZrO3. This figure is quoted with permission from Yang et al.[134]. ESP: Energy storage performance; RFE: relaxor ferroelectric; BDS: dielectric breakdown strength.

The impact of composite architectures on polarization response is inherently multifaceted. A key advantage of such composites lies in their ability to leverage and synergize the functional merits of each constituent phase. Accordingly, the selection of end-member phases is typically guided by their complementary properties. One common strategy involves pairing a component possessing intrinsically high polarization capability with another phase, either crystalline or amorphous, that provides superior dielectric BDS. Alternatively, a high-polarization material may be coupled with a secondary phase known for its superior η, thereby balancing Wrec and η within a single composite system. Nonetheless, it is crucial to emphasize that the realization of these synergistic effects critically depends on the reproducibility and precision of the composite fabrication process. Achieving optimal performance requires the formation of dense microstructures with well-defined and stable interfaces. Care must be taken to prevent undesirable interdiffusion between phases, which can otherwise compromise the intrinsic functionalities of the individual components. Controlled phase distribution, grain boundary engineering, and sintering protocols, therefore, play an essential role in translating microstructural advantages into macroscopic dielectric performance.

Core-shell structures

In ceramic materials, the term “core-shell structure” commonly refers to grains exhibiting radial compositional gradients or inhomogeneities. It is important to clarify that the core-shell strategy discussed in this section pertains exclusively to microstructural design at the grain level within sintered ceramics, rather than to particle-level core-shell configurations formed during powder synthesis. For example, BT particles coated with SiO2 through chemical modification are frequently referred to as core-shell powders. However, upon sintering, the SiO2 coating typically transforms into an amorphous intergranular network. As such, this structural motif should be more appropriately classified under the domain of grain boundary engineering, rather than as a genuine core-shell structure within the ceramic grains. The distinction between these two strategies is fundamental and warrants careful attention by the reader.

Analogous to the 0-0 type composite ceramics described earlier, core-shell structured grains can be regarded as a particular form of compositional or structural heterogeneity, and thus constitute a subclass of composite ceramics. In practice, this design approach is often coupled with grain refinement and has found widespread application in contemporary BT-based MLCC[136], where both dielectric performance and reliability critically depend on the intricate interplay between grain size and microstructure. The core-shell model has been extensively employed to rationalize the influence of grain size on the FE and dielectric properties of ceramics[137,138].