Moisture-induced iontronics for self-powered electronics

Abstract

Moisture-induced iontronic devices represent an emerging technological paradigm that utilizes the interaction between water molecules and functional nanomaterials to generate electricity, enable sensing, and even manipulate information. This emerging technology primarily relies on moisture absorption to trigger ion dissociation and establish directional transport through asymmetric structures or chemical gradients. This perspective summarizes advances in moisture-enabled energy conversion mechanisms, including moisture-induced concentration gradients, streaming potential, and osmotic power generation. Beyond energy harvesting, we extend our scope to explore the burgeoning applications of moisture-induced iontronics in self-powered sensing, proton gating, information writing/reading, and their potential in neuro-inspired biomimetic systems. By detailing fundamental mechanisms, material/structural designs, and diverse applications, this perspective outlines the trajectory of this field from electricity generation to advanced ionic control, while also addressing key challenges and future directions.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

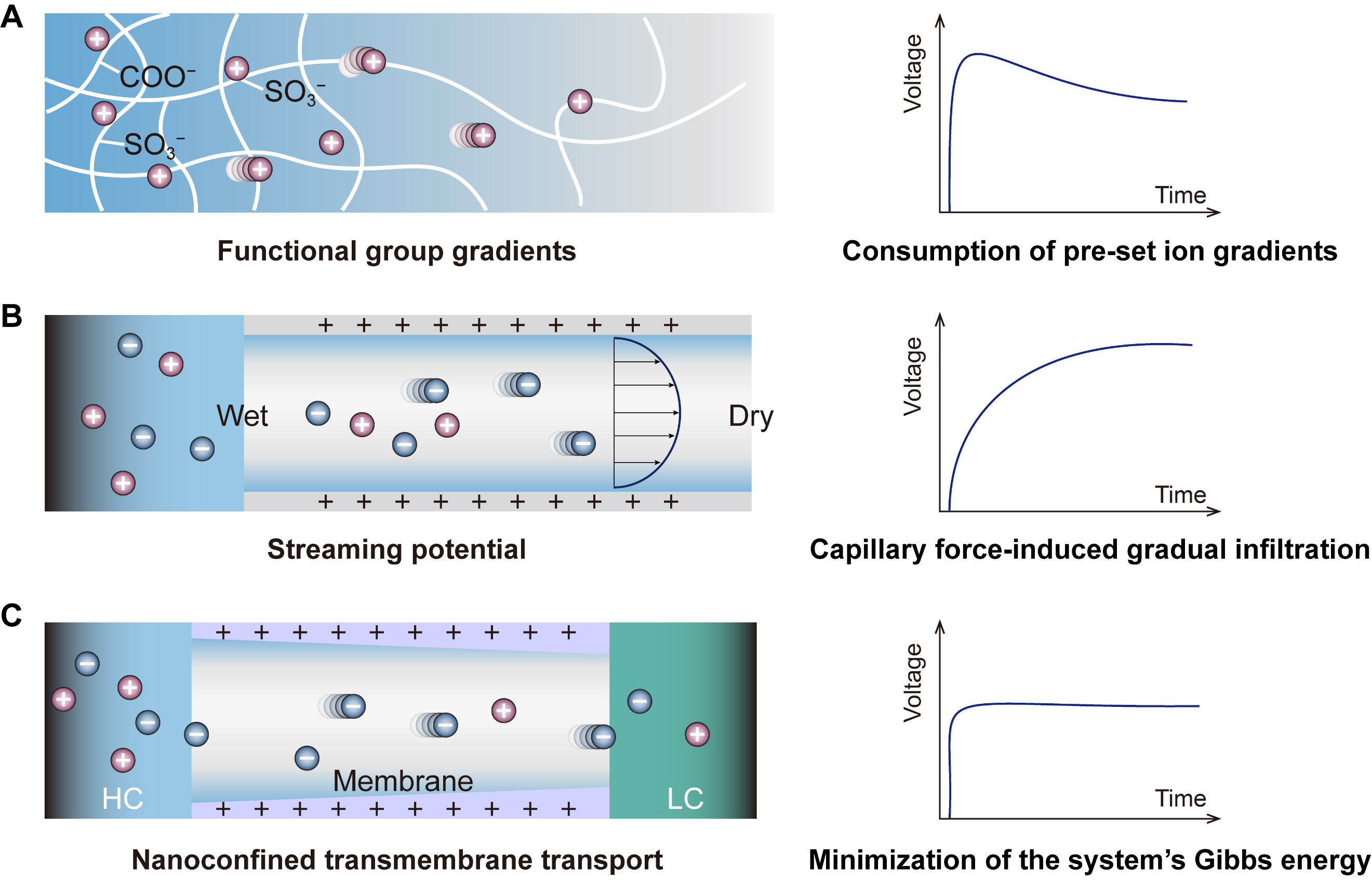

Water, in its various forms, is not only essential for life but has also emerged as a medium for energy technologies[1,2,3]. Among these, moisture-induced iontronic devices (MIDs) have attracted significant attention by converting moisture gradients and fluctuations into electrical signals[4,5]. These systems convert the chemical potential of gaseous water into electrical signals or modulate ion transport within nanostructured materials, enabling broad applications without liquid electrolytes[6-10]. The core mechanism involves asymmetric designs - such as functional group gradients, streaming potentials, or nanoconfined transmembrane ion transport - that direct the movement of dissociated ions upon moisture absorption, leading to ion transport and electricity generation[3,11-13].

Initially focused on sustainable energy harvesting, the scope of MIDs has rapidly expanded[14,15]. Early demonstrations showed that devices could generate electricity from ambient humidity, enabling self-powered electronics[4]. Subsequent results revealed that the analogous ion transport exhibits exceptional sensitivity to environmental stimuli such as pressure[16,17], temperature[18,19], and light[20,21], making them ideal for multi-modal sensing. More recently, the field has evolved beyond energy and sensing into proton gating, information manipulation, and bio-inspired artificial synapses and ionic logic operations[22].

This perspective aims to provide a concise yet comprehensive overview of this evolving field. We begin by clarifying fundamental mechanisms, from moisture-induced electricity generation to solid-state osmotic energy conversion. We then discuss material and structural strategies that enhance device performance and confer sensing properties. The core section explores the diverse applications, from self-powered sensing to the more advanced proton gating, and information processing. Finally, we summarize the current state of the art and offer an outlook on future challenges, highlighting the transition of MIDs from simple power sources to advanced iontronic systems.

ENERGY HARVESTING PROPERTIES

The key to the MIDs lies in triggering and sustaining asymmetric ion transport[11]. Most generalized MIDs are based on pre-set ion gradients or differentiated functional group distributions to drive ion dissociation and transport upon moisture stimulation [Figure 1A][11]. The functional group gradient-enabled MID was first reported in 2015[23]. Typically, one side of such devices is rich in functional groups or ions, capable of dissociating to release abundant ions, forming a concentration gradient with the region deficient in functional groups or ions. In hydrovoltaic-based MIDs, spontaneous capillary infiltration or evaporation within nanoconfined spaces can generate volt-level electricity - driven by pressure gradients, which facilitate the transport of counter-ions through charged nanochannels while excluding flowing co-ions - distinguishing it from osmotic energy conversion by operating independently of external electrolyte concentration gradients[13,24]. As shown in Figure 1B, by integrating highly hygroscopic functional layers into the hydrovoltaic devices, electricity can be generated directly from adsorbed moisture, reducing dependence on bulk water[11,25,26].

Figure 1. Working mechanisms of moisture-induced iontronic electricity generation. (A) Functional group gradient-induced electricity generation; (B) Streaming potential-induced electricity generation; (C) Solid-state nanoconfined transmembrane transport-induced electricity generation. HC: High concentration; LC: low concentration.

Osmotic energy conversion directly converts the Gibbs free energy released when two solutions of different concentrations are mixed into electricity[2]. This process fundamentally relies on an ion-selective membrane serving as its most critical component. Both cations and anions tend to diffuse spontaneously from the high-concentration side to the low-concentration side. It is the membrane that strategically breaks this symmetric diffusion - by selectively restricting the transport of either cations or anions - thereby generating a net directional ionic flow [Figure 1C][3,27]. While conventional osmotic energy conversion requires bulk salt solutions, some reports indicate that all-solid-state devices can utilize moisture adsorption to trigger ion dissociation and facilitate ion transport. Such solid-state systems are generally composed of moisture-sensitive nanomaterials, such as graphene oxides (GO), which promote dissociation and migration by adsorbing water[6,7,28]. Moisture ensures the connectivity of nanochannels and ion migration capability throughout the GO membrane, enabling the concentration gradient to be effectively converted into electricity. Consequently, high humidity is required to sustain internal moisture and ion exchange, whereas low humidity may restrict ion transport and degrade device performance.

SELF-POWERED SENSING

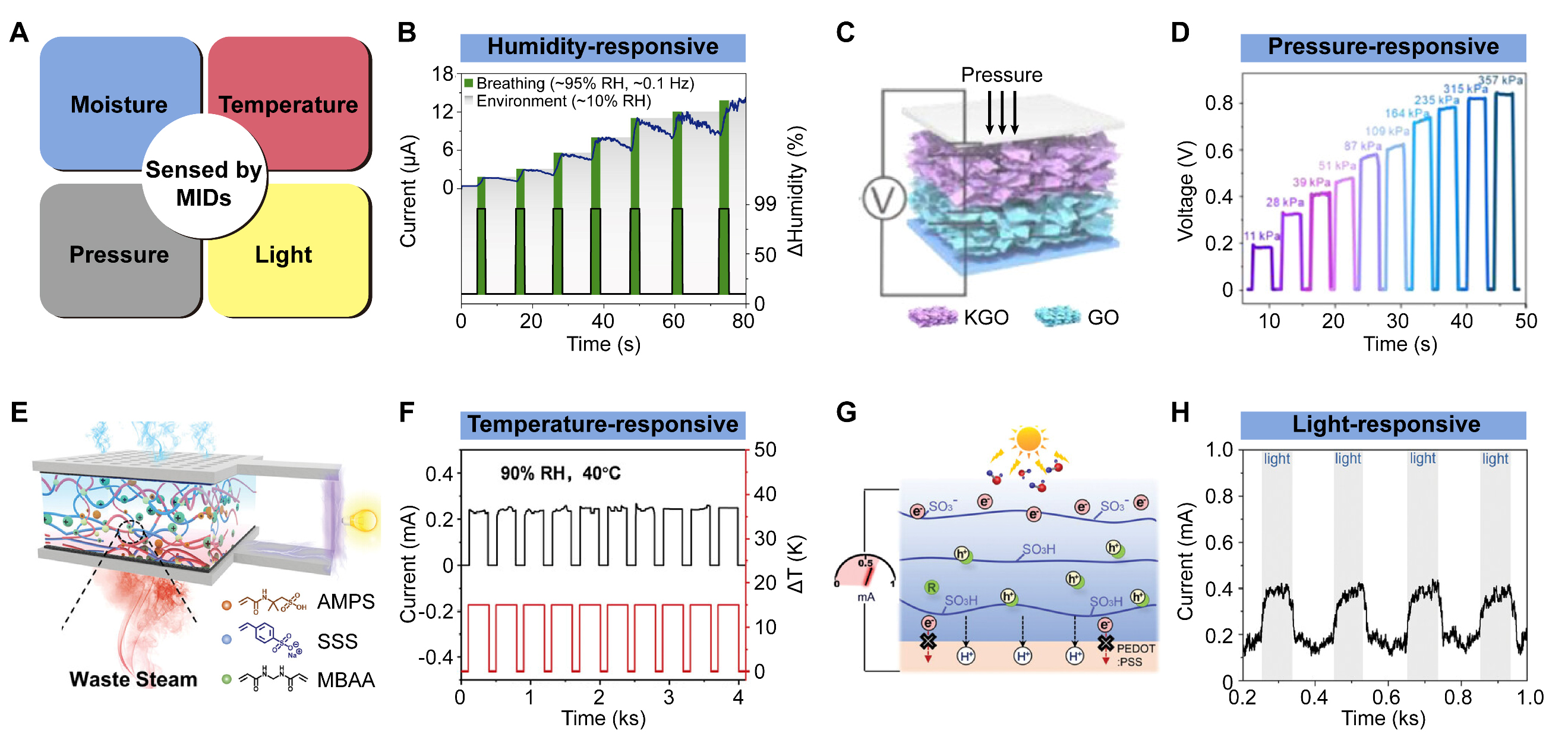

MIDs harvest energy directly from ambient humidity, opening pathways for self-powered systems, particularly in wearable sensing. By converting ubiquitous moisture into electrical signals, MIDs can power sensing functions without external batteries. MIDs can generate electricity using natural humidity while simultaneously perceiving and reflecting changes in local humidity or ion concentration from environmental stimuli[29]. Under conditions of lower ambient humidity, MIDs generally become more sensitive to moisture variations and can detect human respiration. Brief, minute moisture stimuli cause simultaneous adsorption and desorption of moisture within the device, resulting in electrical signal fluctuations [Figure 2A and B][8]. GO, with abundant functional groups, is highly moisture-sensitive and can dissociate protons, enabling ion transport. Applying pressure fields (11 ~ 357 kPa) to GO-derived materials modulates the interlayer spacing of nanosheets, regulating ion transport and enabling pressure-responsive properties [Figure 2C and D][7]. Although moisture does not directly participate in electricity generation, it triggers the dissociation of functional groups, thereby generating free carriers for mechano-electric conversion.

Figure 2. Response and sensing of MIDs under different environmental stimuli. (A) Schematic of multimodal MID-based sensing; (B) Humidity change-induced moisture response. Reprinted with permission. Copyright 2026, WILEY-VCH[8]; (C and D) Moisture-mediated pressure response. Reprinted with permission. Copyright 2025, WILEY-VCH[7]; (E and F) Moisture-mediated temperature response. Reprinted with permission. Copyright 2023, WILEY-VCH[19]; (G and H) Moisture-mediated light response. Reprinted with permission. Copyright 2021, WILEY-VCH[21]. MID: Moisture-induced iontronic device; KGO: KOH-modified graphene oxides; GO: graphene oxides; AMPS: 2-acrylamide-2-methyl propane sulfonic acid; SSS: sodium styrene sulfonate; MBAA: N, N’-methylene bisacrylamide; RH: relative humidity.

Gel/hydrogel materials are considered an effective approach for preparing thermoelectric generators (TEG); however, water evaporation limits their operating temperature range and output stability[19,30]. Integrating MID technology with TEG enables devices to operate continuously under high-temperature and high-humidity conditions. The hygroscopic property of polyelectrolyte membranes compensates for water evaporation, thereby facilitating ion transport and electricity generation. Specifically, through the crosslinking copolymerization of poly(2-acrylamide-2-methylpropane sulfonic acid) and poly(sodium styrene sulfonate), TEG-integrated MID can generate a current of 0.2 mA under conditions of 90% relative humidity and a temperature difference of 15 K [Figure 2E and F][19]. Besides radiating heat, light can also excite photosensitive materials. Based on this principle, Qu et al. reported a light-coordinated MID-based generator, composed of a hybrid film doped with photosensitive materials, capable of simultaneously capturing solar energy[21]. The asymmetric distribution of H+ ions can reduce the recombination of nonequilibrium carriers, thereby enhancing performance. This prototype exhibits significant electrical signal responses to rapid switching of light exposure [Figure 2G and H][21].

UNIQUE APPLICATIONS

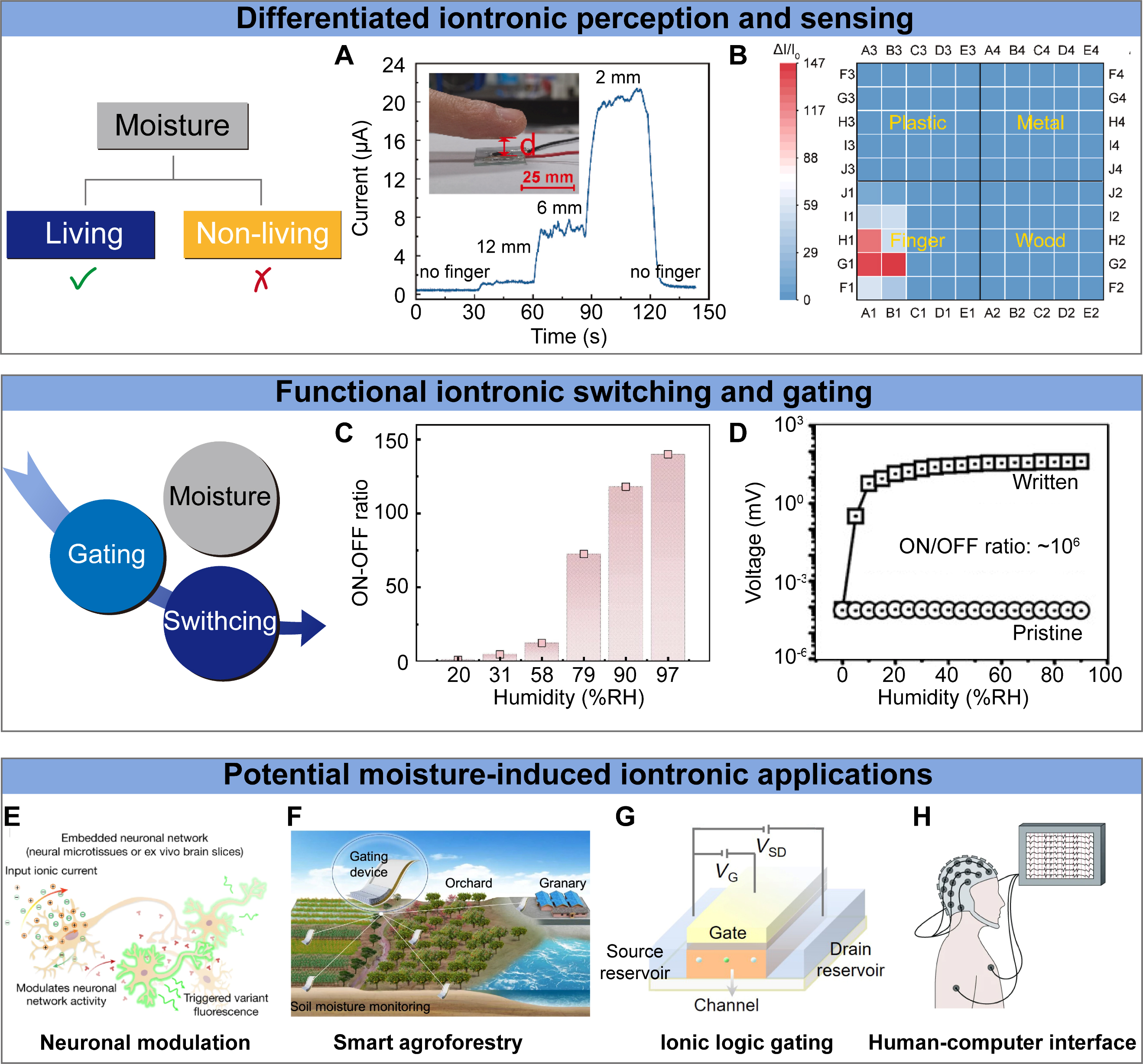

Heterojunctions enable highly efficient selective ion transport, and their integration into MIDs facilitates moisture-induced non-contact sensing, establishing a new paradigm for tactile self-powered sensing. Integrating ionic diode junctions - fabricated by combining the anodic aluminum oxide with carbon nanotubes - into MIDs achieves high detection limits (~ 12 mm), high sensitivity (2.3 mm-1), fast response/recovery (0.3 s/2.5 s) [Figure 3A and B][31].

Figure 3. Unique existing and prospective applications via MIDs. (A and B) Moisture-induced non-contact sensing. Reprinted with permission. Copyright 2024, Elsevier[31]; (C) Moisture-mediated proton gating. Reprinted with permission. Copyright 2025, Springer Nature[14]; (D) Moisture-induced information storage. Reprinted with permission. Copyright 2017, WILEY-VCH[32]; (E) Future applications of MIDs in neuronal modulation. Reprinted with permission. Copyright 2023, Springer Nature[33]; (F) Smart agroforestry. Reprinted with permission. Copyright 2025, Springer Nature[14]; (G) Ionic logic gating. Reprinted with permission. Copyright 2024, AAAS[34]; (H) Human-computer interface. Reprinted with permission. Copyright 2018, Springer Nature[9]. MID: Moisture-induced iontronic device; VG: gate potential; VSD: source-drain bias

A solid-state proton-gating membrane based on a two-dimensional hydrogen-bonded organic framework can achieve ultrahigh ion-gating ratios through humidity-induced switching of proton transport pathways. Combined with the introduction of bacterial cellulose to enhance water cluster kinetics, the membrane achieves a dynamic ON/OFF ratio (~ 0 to ~ 150) under varying humidity conditions [Figure 3C]. Meanwhile, self-powered moisture-powered memristors demonstrate the reversible characteristics of resistive switching and moisture-powered reading through human breath[35]. A MID-type memory device uses moisture ingress to create differentiated ion distributions, analogous to data writing, with an ON/OFF ratio up to 106, surpassing conventional memory devices [Figure 3D][32].

Iontronic systems bridge biological ion conduction and electronic electron transport, thereby reducing impedance at bioelectronic interfaces and enhancing signal transmission[36,37]. Humidity or voltage pulses can mimic action potentials, inducing ion migration and rearrangements that emulate excitatory postsynaptic currents[33]. Ionic diodes made from hydrated hydrogels can replicate the function of hippocampal nerves[38,39]. Droplet-type ionic diodes can also serve as biocompatible and biological ionic current sources to modulate neuronal network activity in three-dimensional neural microtissues and in ex vivo mouse brain slices [Figure 3E][33]. MIDs are also expected to find applications in smart agroforestry, ionic logic, and human-machine interaction [Figure 3F-H][9,14,34]. Meanwhile, the development of practical iontronic logic circuits faces inherent physical constraints. A primary limitation is operational speed: ion migration is orders of magnitude slower than electron drift in semiconductors, inherently restricting some functions[10,40]. Despite these limitations, it offers biointerface compatibility compared to purely electronic systems. Hydrogels are particularly promising for constructing biocompatible iontronic interfaces. Their tissue-like softness and high water content enable seamless integration with biological tissues, minimizing interfacial stress and the sense of foreignness. Compared to purely ionic systems, it possesses richer functional properties, including passive sensing and perception capabilities.

CHALLENGES AND PERSPECTIVES

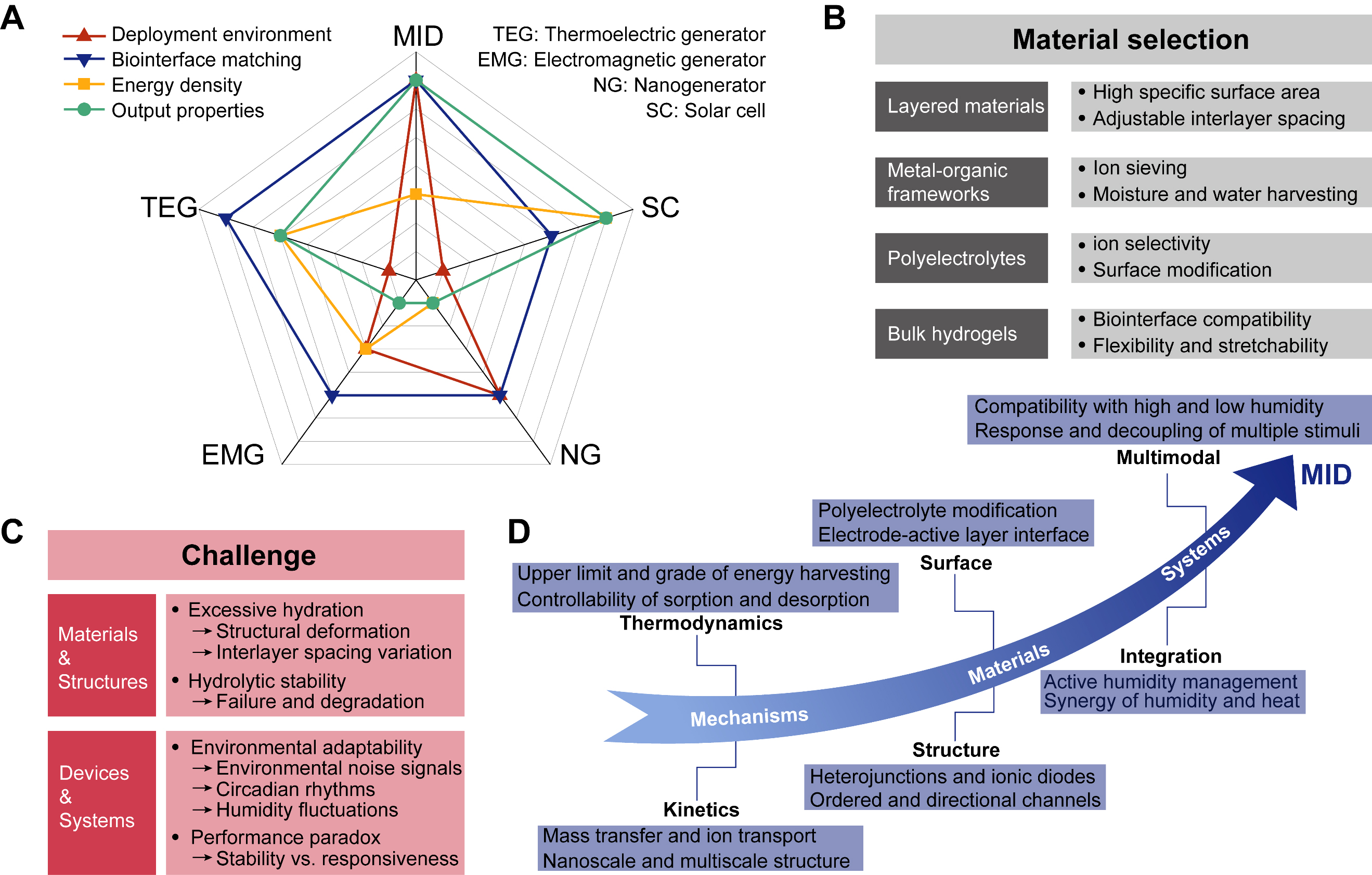

MIDs demonstrate distinctive advantages in deployment environment, biointerface compatibility, and stable direct-current output [Figure 4A]. At the material level, the fabrication of MIDs has encompassed materials ranging from low-dimensional layered materials to bulk hydrogel materials [Figure 4B]. Additionally, metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) and polyelectrolytes can also be incorporated into the fabrication of MIDs, either due to their carefully engineered pores and sites or owing to their outstanding ionic conductivity and modifiable properties. However, key challenges in materials include excessive hydration, structural deformation, and variations in interlayer spacing, which can degrade performance over time [Figure 4C]. On the device scale, environmental factors such as humidity fluctuations, circadian rhythms, and external noise signals complicate real-world deployment. A notable performance paradox exists between achieving high stability and maintaining fast responsiveness. Additionally, ensuring environmental adaptability while minimizing interference from ambient variables presents an ongoing design challenge.

Figure 4. Summary and perspective of MIDs. (A) Horizontal comparisons of the five main self-powered systems. (B) Summary of material selection for MID preparation. (C) Summary of challenge for MIDs. (D) Forward-looking roadmap for advancing MIDs. MID: Moisture-induced iontronic device; TEG: thermoelectric generators; SC: solar cells; EMG: electromagnetic generators; NG: nanogenerators.

Looking forward, the development roadmap for MID technology focuses on advancing fundamental mechanisms, such as thermodynamics and kinetics [Figure 4D]. Thermodynamic efforts encompass the design of adsorbents capable of achieving controllable moisture adsorption and desorption; kinetic aspects may focus on the design of mass transfer and ion transport within MIDs. Incorporating nanoscale structures, directional structures, or multiscale porous structures facilitates moisture adsorption and ion transport, thereby enhancing multiple performance properties.

Throughout the process from materials to device fabrication, efforts should focus on surface modification to ensure both moisture absorption and stability. Meanwhile, materials can be directly used for MID fabrication or combined according to specific requirements - such as modifying layered materials’ surface charge density with polyelectrolytes or using hydrogels as frameworks to load layered materials. Structurally, emphasis should be placed on novel configurations such as heterojunctions or directional channels to enhance ion transport efficiency.

Future efforts will also focus on system-level integration and multimodal design. This necessitates addressing active humidity management and regulation within MIDs. Furthermore, to advance MIDs towards practical application, consideration must be given to their stable operation across a wide range of humidity conditions, alongside their response to and decoupling from multiple environmental stimuli.

DECLARATIONS

Authors’ contributions

Writing original draft: Ni, K.; Liu, R.

Writing, review & editing: Ni, K.; Liu, R.

Supervision: Liu, R.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Financial support and sponsorship

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (52103306), Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (BK20210719), and Natural Science Foundation of Suzhou (ZXL2023181).

Conflicts of interest

Liu, R. is an Editorial Board Member of the journal Iontronics. Liu, R. was not involved in any steps of the editorial process, notably including reviewers’ selection, manuscript handling, or decision-making. The other author declares that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026.

REFERENCES

2. Zhang, Z.; Wen, L.; Jiang, L. Nanofluidics for osmotic energy conversion. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2021, 6, 622-39.

3. Fan, K.; Zhou, S.; Xie, L.; et al. Interfacial assembly of 2D graphene-derived ion channels for water-based green energy conversion. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, e2307849.

4. Xu, T.; Ding, X.; Cheng, H.; Han, G.; Qu, L. Moisture-enabled electricity from hygroscopic materials: a new type of clean energy. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, e2209661.

5. Shen, D.; Duley, W. W.; Peng, P.; et al. Moisture-enabled electricity generation: from physics and materials to self-powered applications. Adv. Mater. 2020, 32, e2003722.

6. Yang, F.; Peng, P.; Yan, Z.; et al. Vertical iontronic energy storage based on osmotic effects and electrode redox reactions. Nat. Energy. 2024, 9, 263-71.

7. Yu, G.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, M.; et al. Osmotic energy directly driving flexible all-solid-state 2D nanofluidic pressure sensors. Adv. Mater. 2025, 37, e06990.

8. Ni, K.; Ren, Q.; Zhang, X.; Liu, R. A trilayer nanofluidic ionic diode for high-performance moisture-enabled energy harvesting and ionic logic operations. Adv. Mater. 2026, 38, e13405.

10. Bisri, S. Z.; Shimizu, S.; Nakano, M.; Iwasa, Y. Endeavor of iontronics: from fundamentals to applications of ion-controlled electronics. Adv. Mater. 2017, 29, 1607054.

11. Ni, K.; Ren, Q.; Liu, S.; et al. Advances in asymmetric moist-electric generators with innovative heterogeneous structures. Energy. Environ. Sci. 2024, 17, 9406-24.

12. Xiao, H.; Yu, Z.; Liang, J.; et al. Wetting behavior-induced interfacial transmission of energy and signal: materials, mechanisms, and applications. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, e2407856.

13. Ni, K.; Xu, B.; Wang, Z.; et al. Ion-diode-like heterojunction for improving electricity generation from water droplets by capillary infiltration. Adv. Mater. 2023, 35, e2305438.

14. Lei, D.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, S.; Jiang, L.; Zhang, Z. High-performance solid-state proton gating membranes based on two-dimensional hydrogen-bonded organic framework composites. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 754.

15. Duan, W.; Shao, B.; Wang, Z.; et al. Silicon nanowire/ionic hydrogel-based hybrid moist-electric generators with enhanced voltage output and operational stability. Energy. Environ. Sci. 2024, 17, 3788-96.

16. Shen, D.; Xiao, M.; Zou, G.; Liu, L.; Duley, W. W.; Zhou, Y. N. Self-powered wearable electronics based on moisture enabled electricity generation. Adv. Mater. 2018, 30, e1705925.

17. Yin, J.; Liu, N.; Jia, P.; et al. MXene‐enhanced environmentally stable organohydrogel ionic diode toward harvesting ultralow‐frequency mechanical energy and moisture energy. SusMat 2023, 3, 859-76.

18. Fang, J.; Zhang, X.; Duan, P.; et al. Efficient and cold-tolerant moisture-enabled power generator combining ionic diode and ionic hydrogel. Mater. Horiz. 2024, 11, 1261-71.

19. Yang, M.; Hu, Y.; Zheng, S.; Liu, Z.; Li, W.; Yan, F. Integrated moist-thermoelectric generator for efficient waste steam energy utilization. Adv. Sci. (Weinh). 2023, 10, e2206071.

20. Bai, J.; Liao, Q.; Yao, H.; et al. Self-induced interface enhanced moisture-harvesting and light-trapping toward high performance electric power generation. Energy. Environ. Sci. 2023, 16, 3088-97.

21. Bai, J.; Huang, Y.; Wang, H.; et al. Sunlight-coordinated high-performance moisture power in natural conditions. Adv. Mater. 2022, 34, e2103897.

22. Ge, Z.; Guo, W.; Tao, Y.; et al. Ambient moisture-driven self-powered iontophoresis patch for enhanced transdermal drug delivery. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2024, 13, e2401371.

23. Zhao, F.; Cheng, H.; Zhang, Z.; Jiang, L.; Qu, L. Direct power generation from a graphene oxide film under moisture. Adv. Mater. 2015, 27, 4351-7.

24. Zhang, Z.; Li, X.; Yin, J.; et al. Emerging hydrovoltaic technology. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2018, 13, 1109-19.

25. Tan, J.; Fang, S.; Zhang, Z.; et al. Self-sustained electricity generator driven by the compatible integration of ambient moisture adsorption and evaporation. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 3643.

26. Hu, Y.; Yang, W.; Wei, W.; et al. Phyto-inspired sustainable and high-performance fabric generators via moisture absorption-evaporation cycles. Sci. Adv. 2024, 10, eadk4620.

27. Qian, H.; Fan, H.; Peng, P.; et al. Biomimetic Janus MXene membrane with bidirectional ion permselectivity for enhanced osmotic effects and iontronic logic control. Sci. Adv. 2025, 11, eadx1184.

28. Wei, D.; Yang, F.; Jiang, Z.; Wang, Z. Flexible iontronics based on 2D nanofluidic material. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 4965.

29. Tan, J.; Wang, X.; Chu, W.; et al. Harvesting energy from atmospheric water: grand challenges in continuous electricity generation. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, e2211165.

30. Kim, B.; Na, J.; Lim, H.; Kim, Y.; Kim, J.; Kim, E. Robust high thermoelectric harvesting under a self‐humidifying bilayer of metal organic framework and hydrogel layer. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2018, 29, 1807549.

31. Zhang, Y.; Long, D.; Feng, H.; et al. Bioinspired ion channel receptor based on hygroelectricity for precontact sensing of living organism. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2024, 247, 115922.

32. Zhao, F.; Wang, L.; Zhao, Y.; Qu, L.; Dai, L. Graphene oxide nanoribbon assembly toward moisture-powered information storage. Adv. Mater. 2017, 29, 1604972.

33. Zhang, Y.; Riexinger, J.; Yang, X.; et al. A microscale soft ionic power source modulates neuronal network activity. Nature 2023, 620, 1001-6.

34. Liu, W.; Mei, T.; Cao, Z.; et al. Bioinspired carbon nanotube-based nanofluidic ionic transistor with ultrahigh switching capabilities for logic circuits. Sci. Adv. 2024, 10, eadj7867.

35. Tao, Y.; Wang, Z.; Xu, H.; et al. Moisture-powered memristor with interfacial oxygen migration for power-free reading of multiple memory states. Nano. Energy. 2020, 71, 104628.

36. Zhang, J.; Liu, W.; Dai, J.; Xiao, K. Nanoionics from biological to artificial systems: an alternative beyond nanoelectronics. Adv. Sci. (Weinh). 2022, 9, e2200534.

37. Ro, Y. G.; Na, S.; Kim, J.; et al. Iontronics: neuromorphic sensing and energy harvesting. ACS. Nano. 2025, 19, 24425-507.

38. Han, S. H.; Kim, S. I.; Oh, M. A.; Chung, T. D. Iontronic analog of synaptic plasticity: Hydrogel-based ionic diode with chemical precipitation and dissolution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2023, 120, e2211442120.

39. Jiang, F.; Poh, W. C.; Chen, J.; et al. Ion rectification based on gel polymer electrolyte ionic diode. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 6669.

Cite This Article

How to Cite

Download Citation

Export Citation File:

Type of Import

Tips on Downloading Citation

Citation Manager File Format

Type of Import

Direct Import: When the Direct Import option is selected (the default state), a dialogue box will give you the option to Save or Open the downloaded citation data. Choosing Open will either launch your citation manager or give you a choice of applications with which to use the metadata. The Save option saves the file locally for later use.

Indirect Import: When the Indirect Import option is selected, the metadata is displayed and may be copied and pasted as needed.

About This Article

Copyright

Data & Comments

Data

Comments

Comments must be written in English. Spam, offensive content, impersonation, and private information will not be permitted. If any comment is reported and identified as inappropriate content by OAE staff, the comment will be removed without notice. If you have any queries or need any help, please contact us at support@oaepublish.com.