Bio-inspired heterointerfacial ion-gating and iontronic neuromorphics

Abstract

The human nervous system communicates through efficient ion-mediated processes, motivating the development of iontronic systems that emulate its adaptive and low-power information processing. Specifically, ion-selective transport and the kinetic hysteresis of biological ion channels form the foundation of neural signaling, including selective transmission, temporal plasticity, and memory effects. Here, we introduce bio-inspired heterointerfacial ion-gating mechanisms within soft-matter iontronic frameworks to realize controllable ionic signal transmission. By engineering cascaded interfaces derived from microphase-separated heterointerfaces within a three-dimensional architecture, the system generates ion-dependent energy landscapes that couple species-level selectivity with tunable transport dynamics. Building on recent advances in microphase-separated gels and droplet-based iontronics, we identify potential key design principles and functional rules for programming multi-ionic signaling and neuromorphic responses into soft-matter iontronic systems. More importantly, we outline future opportunities where ion-gated iontronic neuromorphics could utilize different ionic species as a specific language to construct soft biointegrated sensing, adaptive neuromodulation, and energy-efficient information processing.

Keywords

ION TRANSMISSION IN NEURAL NETWORKS

The human brain, composed of nearly 1011 neurons interconnected through about 1015 synapses, represents one of the most energy-efficient information-processing systems known[1,2]. It executes highly complex cognitive tasks, such as recognition, reasoning, risk evaluation, and decision-making, while consuming only about 20 W of power, far below that required by artificial computational architectures to achieve comparable performance[2,3]. This exceptional efficiency arises not only from the massively parallel organization and hierarchical connectivity of neural circuits, but also from the use of ions as information carriers. These ionic carriers encode rich neural information and support diverse signaling modalities that are essential for communication across neuronal networks.

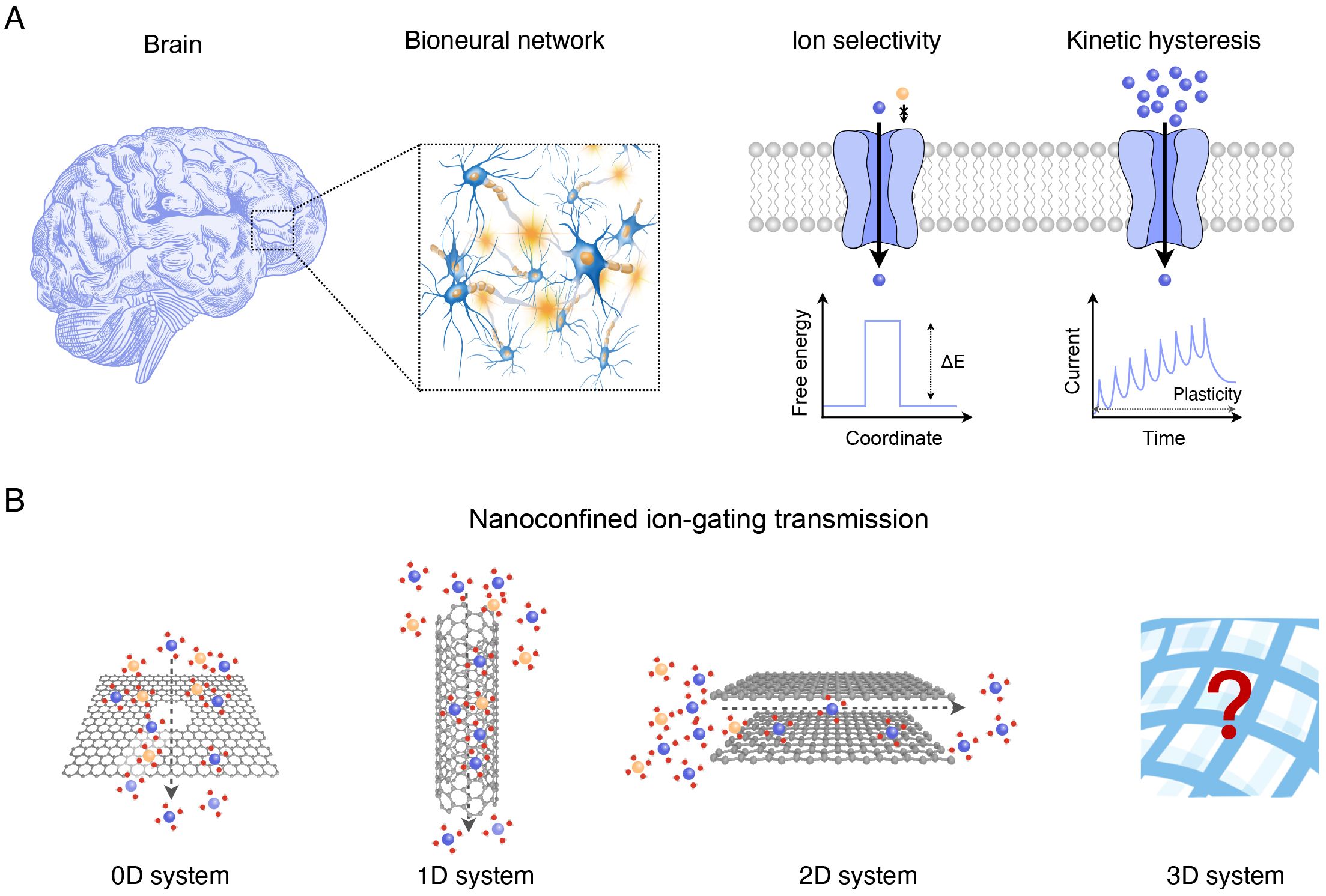

At the microscopic level, the core of neural communication is governed by two intrinsic transport characteristics: ion selectivity and kinetic hysteresis [Figure 1A]. For ion selectivity, it arises from the exquisite structural and chemical specificity of biological ion channels, which discriminate ions based on their hydrated radius, charge density, and interaction energy with the channel’s binding sites[4]. Upon channel activation, the coordination environment within the pore becomes matched to the dehydrated size and energetic profile of the target ion. This matching enables energetically favorable transport, while ions with mismatched hydration or interaction energies are effectively excluded[5]. This selective recognition not only preserves the precision of neurotransmission but also enables different ionic species to carry distinct physiological functions. For kinetic hysteresis, it emerges from the dynamic interplay between ion permeation, transient blocking, and recovery within these confined channels. As ions cross narrow, highly polar interfaces, steric hindrance and energetic mismatches induce short-lived trapping or delayed release. These effects generate time-dependent plasticity in ionic flux[6]. Such transport lag introduces a history dependence, where the present conductance state of a synapse partially reflects its previous activation, thus forming the biophysical basis of short-term and long-term plasticity. Synaptic memory emerges naturally from these ionic processes: repeated stimulation modifies the hydration structures, occupancy states, and conformational configurations of ion channels, ultimately reshaping synaptic efficacy. Taken together, these biological principles indicate that neural information processing depends not only on neuronal network connectivity, but also on the physicochemical rules governing ion transport across confined interfaces. This dual dependence on ion selectivity and temporal plasticity provides essential design cues for the development of artificial ion-based systems. By drawing on these natural transport patterns, iontronics offer a route toward artificial platforms that communicate through a native ionic language, enabling neuromorphic functions such as real-time ionic signaling and adaptive learning across bio-nonbio interfaces and human-machine interaction scenarios.

Figure 1. Ion transmission in neural networks and artificial nanoconfined ion-gating systems. (A) Neural ion channels achieve ion selectivity through energy-matched coordination environments and exhibit kinetic hysteresis that serves as the physical basis of temporal plasticity; (B) Low-dimensional ion-gating systems (0D, 1D, 2D) reveal the mechanisms that regulate ultrafast ion-selective transport, providing guiding principles for constructing multi-dimensional ion-gating systems. 0D: Zero-dimensional; 1D: one-dimensional; 2D: two-dimensional; 3D: three-dimensional.

ARTIFICIAL ION-GATING TRANSMISSION

The development of iontronic systems stems from a fundamental recognition that ion-based carriers inherently align with the signaling modality of biological neural networks. In contrast to electronics, iontronics employs hydrated ions as information carriers, which are the same physical signals underlying biological neural communication. Moreover, the diversity of ionic species enables ion-gating systems to naturally support functionally differentiated signaling channels that are difficult to realize with electrons alone. Guided by this principle, some important advances in artificial ion-selective transport focused on low-dimensional nanofluidic channels, such as nanopores, nanotubes, and nanosheets, which provided well-defined pathways for regulating species-dependent ion migration [Figure 1B]. In these confined systems, nanoscale dimensions play a decisive role: when the channel size approaches the Debye length, electrical double layers overlap to generate unipolar charge environments that favor the passage of ions with specific valence or polarity. Beyond electrostatic exclusion, nanofluidic interfaces introduce additional selectivity mechanisms, including surface-governed charge regulation, rearrangement of ultrathin hydration shells, and enhanced local electric-field strengths associated with high surface-to-volume ratios[7,8]. These effects collectively establish transport regimes characterized by markedly accelerated ionic mobility, enabling ultrafast ion transmission response and low-energy operation[9,10]. However, although nanofluidic channels can deliver high selectivity and rapid ion transmission, these confined channel systems are intrinsically dependent on a narrowly defined liquid environment, including specific solvent composition and ionic strength. At the same time, their fixed sub-nanometer to nanometer channel dimension provides essentially no volumetric capacity for ion storage. More importantly, extending atomic- or nanoscale channels into three-dimensional architectures with hierarchical spatial complexity remains technically challenging. Fabrication routes that rely on top-down lithography or precise self-assembly are difficult to scale over macroscopic areas, are highly sensitive to process fluctuations, and can inevitably introduce structural defects such as local collapse, pore blockage, and structural heterogeneity. Conversely, existing three-dimensional hydrogels and related soft-matter iontronics offer high water content, mechanical compliance, and biocompatibility, making them attractive as platforms for large-scale ionic architectures[11-13]. Yet their three-dimensional polymer networks intrinsically lack both nanoscale confinement and specific interaction mechanisms with ions, thus ions diffuse essentially freely throughout the iontronics matrix and fundamentally limit the realization of selective ion transport. Therefore, the development of gel-based iontronics that can achieve the spatial precision and species-specific transport characteristic of biological ion channels still remains a major challenge.

Recent advances in heterointerfacial ion-gating systems provide an effective strategy to overcome these limitations by introducing multiple interfacial gating within a high-dimensional soft-matter framework[14-18]. As demonstrated in the cascade-heterogated biphasic-gel iontronics system [Figure 2A], spontaneous microphase separation generates a network of dispersed, ion-enriched internal phases (IE phase) embedded within a low-conductivity continuous phase (LC phase). Each interphase boundary forms a heterointerface with distinct polarity and steric constraints, constructing the microphase-separated heterointerficial system with three-dimensional architecture. Specifically, the internal phase is typically ion-enriched and highly hydrophilic to enable ion storage and hydrated-ion transport, whereas the continuous phase is less polar and low-conductive, introducing partial dehydration and transport resistance. As ions cross these heterointerfaces, they undergo repeated hydration–partial dehydration–rehydration transitions, making the transfer free-energy barrier strongly dependent on each ion’s intrinsic hydration-dehydration energy.

Figure 2. Heterogated biphasic-gel iontronics with selective ionic transmission and promising ion-selective neuromorphic functional applications. (A) Heterogated biphasic-gel iontronics employ cascaded interfacial energy barriers to establish hierarchical ion-transport pathways, achieving species-dependent ionic responses and selective transmission; (B) Ion-selective and time-dependent transport produces neuromorphic ionic behaviors, including species-dependent hysteresis and excitatory-post-synaptic-current-like (EPSC-like) responses that would integrate short-term and long-term dynamics through different ionic carriers; (C) Prospective applications of heterointerfacial iontronics within ion-selective neuromorphic processors for low-energy neuromorphic sensing and computation.

Molecular dynamics simulations and theoretical analysis show that this cascaded heterointerface architecture amplifies the intrinsic energetic differences between ions (ΔEFe³⁺ > ΔECa²⁺ > ΔEK⁺). From a physical standpoint, this amplification can be understood using an equivalent series-resistance picture, in which each heterointerface contributes an ion-specific interfacial transport resistance associated with its transfer free-energy barrier. When multiple heterointerfaces are arranged in series, these ion-dependent resistances accumulate, causing small intrinsic differences at a single interface to grow progressively with increasing cascade degree. As a result, the cascaded architecture produces several-orders-of-magnitude contrasts in signal intensity and distinct activation voltages for K+, Ca2+, and Fe3+ that cannot be achieved in homogeneous hydrogels.

Under increasing pulse amplitudes, the ionic signals of K+, Ca2+, and Fe3+ are activated sequentially, while in the absence of bias, the heterogated iontronics can stably store ions without uncontrolled leakage into the external solution. These results demonstrate that three-dimensional heterointerfacial ion-gating gels can support ion-specific transport kinetics, multiple ionic signaling, and hierarchical regulation of ionic flux. The introduction of selective ligands into the IE phase further enables “chemical heterogating”, in which ligand-mediated hopping transport reshapes the overall energy landscape and allows Ca2+ to be selectively transmitted across stages against the original hydration-energy hierarchy. Moreover, coupling the heterogated iontronics gel device with electronic driving circuits and a bullfrog heart preparation demonstrates that electronically programmed multi-ionic outputs can effectively modulate cardiomyocyte ion fluxes and cardiac electrical activity. These results highlight the potential of heterointerfacial gels as soft, biocompatible transduction media for multi-species ionic signal processing at abiotic-biotic interfaces. Beyond enabling multi-ionic hierarchical transmission, these iontronic systems also reshape ionic transport kinetics, giving rise to nonlinear conduction behaviors such as asymmetric current-voltage responses and rectification. In droplet-assembled iontronic systems, such kinetic modulation arises from the heterojunctions formed between oppositely charged hydrogel droplets, where ion transport is governed by interfacial charge asymmetry and field-dependent ion redistribution. Similar nonlinear gating phenomena have been observed in droplet-based iontronic diodes[16], where the microphase-separated heterojunction generates current ratios exceeding two orders of magnitude under forward and reverse bias. In these systems, the droplet volume, interfacial contact area, and network connectivity provide tunable parameters to regulate interfacial resistance and ionic relaxation dynamics. These nonlinear responses indicate that interfaces function not merely as conduction pathways but as active ionic modulators that allow transport characteristics to evolve under applied fields. Such dynamically regulated ion motion gives rise to threshold-like behavior and history-dependent conduction, features that reflect essential elements of neural information processing. Together, these capabilities establish a foundation for achieving precise spatiotemporal control over ion transmission across material scales. From a broader perspective, such three-dimensional ion-gating systems represent a promising soft material framework for constructing iontronic platforms that are intrinsically low-power, adaptive, and biocompatible. Their ability to replicate core features of biological ion transport, including selectivity, gating, and multiplexed signaling, opens pathways toward intelligent sensing systems, neuromodulation devices, and next-generation brain–machine interfaces that operate seamlessly within ion-mediated biological environments.

ION-SELECTIVE NEUROMORPHIC FUNCTIONALITIES AND PROMISING APPLICATIONS

The emergence of neuromorphic functionalities in artificial iontronic systems stems from their ability to couple ion selectivity with temporally modulated transport, two hallmarks that define biological neural signaling. In low-dimensional nanofluidic systems, nanoscale confinement, electric-double-layer overlap, and asymmetric channel geometries have enabled rectified ion transport, ionic hysteresis, and history-dependent conductance states, the phenomena that mirror elementary forms of synaptic response and short-term memory[19-23]. These systems demonstrate that, when ion motion is shaped by tailored interfacial energetics and confined geometries, artificial materials can exhibit neuromorphic-like behaviors without relying on biochemical pathways. Despite these advances, translating ion-selective neuromorphic principles into three-dimensional ion-gating systems remains profoundly challenging. Addressing this challenge is critical for advancing soft iontronic systems beyond simple ionic conductors toward platforms capable of encoding, processing, and adapting ionic information in a manner analogous to biological neural tissue.

The combination of heterointerfacial ion-gating with three-dimensional soft-matter structures may open a promising route toward ion-selective neuromorphic iontronic systems capable of uniting ionic storage, species-level selectivity, and synapse-like temporal plasticity within a single soft-matter platform [Figure 2B]. The energetic asymmetry of cascaded heterointerfaces could allow different ionic species to follow distinct transport pathways, thereby creating parallel multi-ion channels. Such differentiation raises the possibility of designing materials in which fast ions - such as K+ - mediate rapid, excitatory-like responses, while slower carriers - such as Ca2+ or multivalent ions - contribute delayed, modulatory, or inhibitory-like behaviors, resembling the coexistence of multiple signaling modes in neural tissue. Time-dependent ionic responses governed by interface-induced kinetics could generate synthetic short-term facilitation, temporal filtering, or adaptive thresholding. More persistent external field stimulation may establish artificial analogs of long-term potentiation or depression, without requiring complex biochemical cascades. This perspective highlights that neuromorphic function does not require the biological machinery of phosphorylation or structural remodeling; instead, it can arise from the fundamental physics of ion motion through a tailored, energetically structured medium.

The ability to program species-specific transport and temporally resolved ionic responses within three-dimensional ion-gating systems may unlock a broader landscape of ion-selective neuromorphic applications [Figure 2C]. Different ionic species possess distinct valence states, hydration energetics, and mobilities. Selective ion gating therefore enables a single material system to generate multi-ionic outputs. These differentiated ionic signals can resemble excitatory, inhibitory, or modulatory pathways, analogous to functional roles in biological neural circuits. Such signaling offers opportunities for soft human-machine interfaces in which ion-specific signals mediate adaptive tactile perception, closed-loop reflex-like responses, or dynamic neuromodulation between biological and synthetic systems. Beyond signal transmission, materials that serve as distributed ionic nodes may function as ionic processing lattices. Within these lattices, signals can be stored, weighted, and transformed through history-dependent conductance changes. Networks composed of such ion-selective neuromorphic nodes may support associative recognition, temporal integration, and nonlinear filtering. Together, these functions form the basis of compact and low-power neuromorphic architectures, in which each ionic species operates as an independent computational carrier. In these systems, information is no longer transmitted solely through electron flow. Instead, computation and communication occur through diverse ionic pathways that more closely parallel the strategies employed by biological neural tissue. An additional advantage of three-dimensional ion-gating gels lies in their hydrated, adaptive, and biocompatible nature. These properties enable intimate interfacing with biological environments while maintaining mechanical compliance and stable ionic operation[11,12,24,25]. This compatibility positions ion-selective neuromorphic gels as promising candidates for long-term bio-interactive devices, soft prosthetic interfaces, and next-generation intelligent materials capable of seamless communication at the boundary between biological and artificial systems.

Looking forward, advanced three-dimensional ionic neuromorphic platforms may support closed-loop, adaptive behaviors in artificial organs, soft robotics, and biohybrid systems. Their inherent compatibility positions them as promising candidates for next-generation neuromodulation, autonomous therapeutic interfaces, and intelligent biomimetic machines. In these settings, ionic transport serves not only as a communication medium, but also as a computational substrate. This substrate enables sensing, processing, and responsive behaviors to be integrated within a single system. Ultimately, ion-selective neuromorphic iontronics represent a shift away from electron-centric paradigms toward a mode of computation grounded in the physicochemical principles of life. By harnessing heterointerfaces, ionic energetics, and adaptable soft architectures, these systems hold the potential to establish a foundation for soft, energy-efficient, and bio-inspired neuromorphic technologies.

DECLARATIONS

Authors’ contributions

Conceptualization: Zhao, Z.

Writing: Zhu, X.; Zhao, Z.

Visualization: Zhu, X.; Wu, Z.; Zhao, Z.

Supervision: Zhao, Z.

Project administration: Zhao, Z.

Funding acquisition: Zhao, Z.

All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Financial support and sponsorship

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant No. 22275183).

Conflicts of interest

Zhao, Z. is an Editorial Board Member of Iontronics. He had no involvement in the review or editorial process of this manuscript, including but not limited to reviewer selection, evaluation, or the final decision. The other authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2025.

REFERENCES

1. Ji, Y.; Wang, L.; Long, Y.; et al. Ultralow energy adaptive neuromorphic computing using reconfigurable zinc phosphorus trisulfide memristors. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 6899.

2. Yu, L.; Li, X.; Luo, C.; et al. Bioinspired nanofluidic iontronics for brain-like computing. Nano. Res. 2023, 17, 503-14.

3. Modha, D. S.; Akopyan, F.; Andreopoulos, A.; et al. Neural inference at the frontier of energy, space, and time. Science 2023, 382, 329-35.

4. Gouaux, E.; Mackinnon, R. Principles of selective ion transport in channels and pumps. Science 2005, 310, 1461-5.

5. Bernèche, S.; Roux, B. Energetics of ion conduction through the K+ channel. Nature 2001, 414, 73-7.

6. Tilegenova, C.; Cortes, D. M.; Cuello, L. G. Hysteresis of KcsA potassium channel’s activation- deactivation gating is caused by structural changes at the channel’s selectivity filter. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2017, 114, 3234-9.

7. Qian, H.; Fan, H.; Peng, P.; et al. Biomimetic Janus MXene membrane with bidirectional ion permselectivity for enhanced osmotic effects and iontronic logic control. Sci. Adv. 2025, 11, eadx1184.

8. Li, X.; Wang, Z. L.; Wei, D. Scavenging energy and information through dynamically regulating the electrical double layer. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2405520.

9. Sun, Y.; Zhou, K.; Xiao, H.; et al. Immiscible liquid-mediated ultrafast ion transport through nanoconfined channels. Nano. Energy. 2023, 105, 108011.

10. Wang, M.; Hou, X. Building artificial aligned nanochannels for highly efficient ion transport. Joule 2023, 7, 251-3.

11. Zhao, Z.; Fang, R.; Rong, Q.; Liu, M. Bioinspired nanocomposite hydrogels with highly ordered structures. Adv. Mater. 2017, 29, 1703045.

12. Ye, H.; Wu, B.; Sun, S.; Wu, P. Self-compliant ionic skin by leveraging hierarchical hydrogen bond association. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 885.

14. Chen, W.; Zhai, L.; Zhang, S.; et al. Cascade-heterogated biphasic gel iontronics for electronic-to-multi-ionic signal transmission. Science 2023, 382, 559-65.

15. Zhang, Y.; Sun, T.; Yang, X.; et al. A microscale soft lithium-ion battery for tissue stimulation. Nat. Chem. Eng. 2024, 1, 691-701.

16. Zhang, Y.; Tan, C. M. J.; Toepfer, C. N.; Lu, X.; Bayley, H. Microscale droplet assembly enables biocompatible multifunctional modular iontronics. Science 2024, 386, 1024-30.

17. Wu, Z.; Zhao, Z. Heterogating gel iontronics: a revolution in biointerfaces and ion signal transmission. Gels 2024, 10, 594.

18. Chen, W.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, A.; et al. Intercellular ion-gradient piezoheterogated biphasic gel for ultrahigh iontronic generation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2025, 147, 3283-92.

19. Zhou, Y.; Xiong, T.; Lu, J.; et al. Highly-efficient ion gating through self-assembled two-dimensional photothermal metal-organic framework membrane. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2023, 62, e202302997.

20. Wang, J.; Jiang, Y.; Xiong, T.; et al. Optically modulated nanofluidic ionic transistor for neuromorphic functions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2025, 64, e202418949.

21. Xiong, T.; Li, C.; He, X.; et al. Neuromorphic functions with a polyelectrolyte-confined fluidic memristor. Science 2023, 379, 156-61.

22. Robin, P.; Emmerich, T.; Ismail, A.; et al. Long-term memory and synapse-like dynamics in two-dimensional nanofluidic channels. Science 2023, 379, 161-7.

23. Robin, P.; Kavokine, N.; Bocquet, L. Modeling of emergent memory and voltage spiking in ionic transport through angstrom-scale slits. Science 2021, 373, 687-91.

24. Yuk, H.; Wu, J.; Zhao, X. Hydrogel interfaces for merging humans and machines. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2022, 7, 935-52.

Cite This Article

How to Cite

Download Citation

Export Citation File:

Type of Import

Tips on Downloading Citation

Citation Manager File Format

Type of Import

Direct Import: When the Direct Import option is selected (the default state), a dialogue box will give you the option to Save or Open the downloaded citation data. Choosing Open will either launch your citation manager or give you a choice of applications with which to use the metadata. The Save option saves the file locally for later use.

Indirect Import: When the Indirect Import option is selected, the metadata is displayed and may be copied and pasted as needed.

About This Article

Copyright

Data & Comments

Data

Comments

Comments must be written in English. Spam, offensive content, impersonation, and private information will not be permitted. If any comment is reported and identified as inappropriate content by OAE staff, the comment will be removed without notice. If you have any queries or need any help, please contact us at support@oaepublish.com.