The transfer hydrogenation of levulinic acid to γ-valerolactone over CuNiAl catalyst

Abstract

The catalytic performance of heterogeneous catalysts remains a great challenge for large-scale commercial applications under harsh reaction conditions. Herein, we designed a CuNiAl catalyst using a layered double hydroxides precursor, and the catalytic performances were evaluated in transfer hydrogenation of levulinic acid to

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

The increasing consumption of fuels and chemicals is causing environmental and climate changes and the exhaustion of fossil resources[1,2]. Nowadays, producing sustainable fuels and chemicals from renewable biomass has become a crucial goal for chemical researchers. Lignocellulose, the primary component of biomass, can be hydrolyzed and acid-catalyzed to important versatile platform compounds including formic acid (FA), levulinic acid (LA), and others. Various high value-added chemicals, containing γ-valerolactone (GVL), 2-methyltetrahydrofuran and 1,4-pentanediol, can be synthesized from the reduction of LA with

Nevertheless, the widespread commercial application of noble metal catalysts is restricted due to their high cost and scarcity. Thus, developing non-noble metal catalysts is of great advantage and has garnered considerable attention, and some progress has been obtained. For instance, Cu-based catalysts have been generally studied for LA hydrogenation to produce GVL. Xu et al. prepared a Cu/WO3-ZrO2 catalyst on which GVL was produced with a yield of 99% in hydrogenation of LA at conditions of 5 MPa H2, 200 °C,

Herein, we prepared a CuNiAl catalyst using a co-precipitation method with a hydrotalcite-like precursor. The structure of catalysts was well characterized by X-ray diffraction (XRD), high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HRTEM), X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS), hydrogen temperature-programmed reduction (H2-TPR), hydrogen temperature-programmed desorption (H2-TPD), carbon dioxide temperature-programmed desorption (CO2-TPD) and ammonia temperature-programmed desorption (NH3-TPD) methods. The synergistic effects of metallic active species and the acid–base sites of CuNiAl catalyst on the catalytic performances in transfer hydrogenation of LA were discussed. Compared to CuAl, CuNiAl catalyst exhibited outstanding catalytic activity and selectivity and the improved stability. The possible factors affecting the stability under acidic conditions were investigated, and the significant contribution of CuNi species was discussed in detail.

EXPERIMENTAL

Materials and reagents

LA (Sigma-Aldrich, 98%), GVL (Sigma-Aldrich, 99%), nickel nitrate hexahydrate [Ni(NO3)2·6H2O, Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co. Ltd., 99%], copper nitrate trihydrate [Cu(NO3)2·3H2O, Macklin, 99%], aluminum nitrate nonahydrate [Al(NO3)3·9H2O, Xilong Chemical Co. Ltd., 99%], 1,4-dioxane (Aladdin), NaOH (Beijing Chemical Co. Ltd.), Na2CO3 (Beijing Chemical Co. Ltd.), FA (Innochem, > 98%) and anisole (Innochem, ≥ 99.9%) were used without any further purification.

Catalyst preparation

At first, a CuNiAl layered double hydroxides (LDHs) composite was prepared by a coprecipitation method. The corresponding amount of Ni(NO3)3·6H2O, Cu(NO3)2·6H2O and Al(NO3)3·9H2O was dissolved into deionized water (25 mL) to obtain the mixture solution, in which the mole ratio of Cu/Ni/Al of 1/3/2 with the total concentration of Cu2+, Ni2+ and Al3+ fixed at 1 M. Then slowly dropped the solution to Na2CO3 aqueous solution (50 mL, 1M) under vigorous stirring at 40 °C. Subsequently, the pH value of the resulting solution was adjusted to 10 by adding NaOH (4 M). Finally, the mixture obtained was kept constantly stirring for 12 h at 40 °C in a water bath.

The obtained solid composite with LDHs was then calcined in air atmosphere at 400 °C for 4 h and followed by being reduced with a pure H2 flow at 400 °C for 2 h; the resulted solid sample was named CuNiAl catalyst. Besides, for comparison, CuAl with a Cu/Al of 1/2 and NiAl with a Ni/Al of 3/2 were prepared also by the same synthesis step as described above.

Catalyst characterization

Powder XRD patterns of the reduced catalyst were performed on Bruker D8 Advance X-ray diffractometer with Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.54 Å) and a scanning rate of 8°/min at 2θ range of 5-80°. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and HRTEM were performed on a field emission Tecnai G2 F20 instrument at 200 KV. Nitrogen sorption isotherms were measured at -196 °C by Quantachrome Instruments version 4.0. The surface areas were calculated by the t-method external surface area. XPS was recorded on a Thermo Scientific K-Alpha+. The C 1s peak at 284.8 eV was used as a reference for charge-up correction. All catalysts were reduced at 400 °C for 2 h and underwent Argon ion etching to a depth of about 10 nm before each measurement. The content of Cu and/or Ni loading was examined by inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectroscopy (ICP-AES) on Thermo Scientific X series II.

NH3-TPD, CO2-TPD, H2-TPD and H2-TPR results were recorded on a Micromeritics AutoChem II 2920. For NH3-TPD, 50 mg of the sample was in situ reduced at 400 °C for 2 h. Whereafter, the sample was cooled to 50 °C and flowed 10% NH3/He gas (30 mL·min-1) for 30 min. The sample was then introduced with He at 100 °C for 30 min to remove the physically adsorbed NH3 after the NH3 adsorption on the catalyst surface reached saturation adsorption. NH3-TPD profiles were recorded with He (30 mL·min-1) as the carrier stream from 50 to 800 °C with a rate of 10 °C·min-1. CO2-TPD was measured in the same procedure as NH3-TPD, except that adsorbed gas was changed to CO2/He from NH3/He. For H2-TPD measurement, 50 mg of the sample was in situ reduced in a 10% H2/Ar stream (50 mL·min-1) at 400 °C for 0.5 h. After being cooled to

Transfer hydrogenation of LA

The catalytic performance of catalysts was evaluated in the transfer hydrogenation of LA to GVL. At first,

Recycling test

For the recycling test, after the reaction, the catalyst was collected by centrifugation and washed five times with ethanol and three times with 1,4-dioxane. The washed catalyst was then used directly without further treatments with adding fresh substrates of LA and FA for the subsequent run under the identical reaction conditions of 200 °C, 5 mmol LA, 10 mmol FA, 0.1 MPa N2, 50 mg catalyst, 20 mL 1,4-dioxane, 6 h.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Catalyst characterization

At first, the catalysts were characterized by XRD [Figure 1]. All the samples of CuAl, NiAl and CuNiAl prepared without thermal treatment (calcination and reduction) presented characteristic structures of LDHs with (003), (006), (012), (015), (018), (110) and (113) planes at 2θ angles of 10° ~ 65° [Figure 1A]. After calcination in air atmosphere and reduction treatment in H2 atmosphere [Figure 1B], the CuO phase with a diffraction peak at 36.1° and the metallic Cu phase of (111), (200), and (220) with diffraction peaks at 43.3°, 50.4° and 74.1° were observed on the CuAl catalyst[14]. The NiO phase with broad diffraction peaks at 37.3°, 43.3° and 63.5° and the metallic Ni phase with diffraction peaks at 44.5°, 51.6° and 76.5° were presented on the NiAl catalyst[14]. For the CuNiAl catalyst, the diffraction peaks at 43.9°, 51.4° and 75.7° showed a right shift compared to the diffractions of Cu0 in the CuAl catalyst [Figure 1C], indicating the formation of CuNi alloy[23]. For CuNiAl and NiAl, the similar diffraction patterns of Al2O3 phase were observed. The Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) specific surface area, pore size and pore volume of catalysts are listed in Table 1. The specific surface areas do not differ significantly among the catalysts of CuAl, NiAl and CuNiAl, which are around 139~159 m2·g-1. The metal content of catalysts examined by ICP-AES analysis is also shown in Table 1.

Figure 1. XRD patterns of CuAl, NiAl, and CuNiAl catalysts (A) before and (B) after calcination and reduction; (C) Enlarged local image of (B) from 40° to 50°. XRD: X-ray diffraction.

Physical and chemical properties of catalysts

| Samples | SBET (m2·g-1)a | Pore volume (cm3·g-1)a | Pore size (nm)a | Cu content (wt.%)b | Ni content (wt.%)b |

| CuAl | 159 | 0.13 | 4.8 | 16.2 | - |

| NiAl | 153 | 0.38 | 7.8 | - | 52.3 |

| CuNiAl | 139 | 0.11 | 4.8 | 16.1 | 41.9 |

The microstructure and micromorphology of the CuNiAl and CuAl catalysts were characterized by HRTEM images [Figure 2]; except for the Cu (111) planes with lattice distance of 0.21 nm and Ni (111) planes with lattice distance of 0.204 nm, the (111) planes of the CuNi alloy with lattice distance of 0.206 nm were also detected in the CuNiAl catalyst, which agree with the XRD results. The average particle size of metal active species is about 1.31 nm for CuNiAl catalyst, which does not significantly differ from that of the CuAl catalyst (1.43 nm) [Supplementary Figure 2].

Figure 2. HRTEM images of (A) CuNiAl and (B) CuAl catalysts. HRTEM: High-resolution transmission electron microscopy.

The electronic properties and surface composition of catalysts were characterized by XPS [Figure 3]. All catalysts underwent argon ion etching to a depth of about 10 nm before measurement. Four deconvoluted peaks were observed in the Cu 2p XPS spectra of CuAl and CuNiAl catalysts [Figure 3A]. The difference in the binding energy between Cu0 and Cu+ is only 0.1 eV and cannot be distinguished, so the peaks at around 932.3 ± 0.1 eV (2p3/2) and 952.0 ± 0.1 eV (2p1/2) are ascribed to the Cu0/+. The XPS spectra of Cu2+ species appeared at higher binding energies of 933.4 ± 0.1 eV (2p3/2) and 954.3 ± 0.1 eV (2p1/2), consistent with the literature[24]. For the XPS spectra of Ni 2p [Figure 3B], the deconvoluted peaks appeared at 852.0 ± 0.2,

Figure 3. (A) XPS spectra of Cu 2p for CuAl and CuNiAl; (B) XPS spectra of Ni 2p for NiAl, and CuNiAl. XPS: X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy.

The reduction characteristics of the catalysts were studied by H2-TPR [Figure 4A]. The NiAl catalyst displays a small reduction peak at 347 °C and a broad reduction peak at 476 °C. The former was attributed to the reduction of the bulk NiO species that interacted weakly with the support, while the latter was assigned to the reduction of crystalline NiO that interacted strongly[26]. CuNiAl catalyst displays two reduction peaks at approximately 165 and 320 °C, which obviously shift down to lower temperatures compared to NiAl and CuAl. The hydrogen spillover typically occurred on the bimetallic catalysts, influencing the reduction behavior[27,28]. For the present CuNiAl catalyst, the reduction peak moved to lower temperatures as the interaction between Cu and Ni formed CuNi alloy, besides the active hydrogen species dissociated on Cu and spilled over to NiO species accelerating its reduction.

Figure 4. (A) H2-TPR profiles and (B) H2-TPD profiles of CuAl, NiAl and CuNiAl. H2-TPR: Hydrogen temperature-programmed reduction; H2-TPD: hydrogen temperature-programmed desorption.

H2-TPD analysis was performed to investigate the hydrogen adsorption capacity on the catalysts [Figure 4B]. All the catalysts presented two distinct H2 desorption peaks at 70~150 and 450~495 °C, denoted as peaks Ι and Π, respectively. Peak Ι was assigned to the desorption of the hydrogen chemisorbed on the surface metallic Ni or Cu species, while peak Π may be attributed to the hydrogen spilled over on the Al2O3 support. For peak Ι, it is evident that more H2 adsorption is on the NiAl catalyst, indicating a preference for H2 to adsorb on the Ni species. Consequently, the coordination between Ni and Cu resulted in the adsorption of peak I and peak Π on the CuNiAl catalyst shifted to the lower temperatures.

The catalysts acidity by NH3-TPD and alkalinity by CO2-TPD were determined, respectively. The strength of acid sites on the catalysts is shown in Figure 5A; the CuAl and NiAl catalysts showed the weak acid sites with desorption peaks at around 120 °C and the medium acid sites with desorption peaks at 250~300 °C. CuNiAl possesses stronger acid sites with desorption peaks at 300~600 °C. As shown in Figure 5B, all the catalysts have similar weak, medium and strong basic sites with distinct CO2 desorption peaks at temperature ranges of <250, 250~400 and >400 °C. The amounts of total acid sites and basic sites of catalysts are calculated [Supplementary Table 1]; CuNiAl catalysts possess much stronger acid sites and less basic sites on their surface compared with CuAl and NiAl.

Catalytic performance

Various parameters were assessed for the reaction of LA hydrogenation to GVL with FA as a hydrogen donor. As shown in Figure 6A, all the catalysts showed high selectivity (> 98%) for the product GVL, and the activity of the catalyst is in an order of CuAl > CuNiAl > NiAl. For the CuNiAl catalyst, the molar ratio of Cu:Ni:Al significantly influenced activity; the highest activity was achieved with a Cu:Ni:Al ratio of 1:3:2. The conversion of LA reached 91.4%, much higher than the one with Cu:Ni:Al of 1:1:1 (66%) and of 3:1:2 (56%) [Figure 6B]. Moreover, the concentration of the hydrogen donor of FA was examined with a molar ratio of LA:FA at a range varied from 1:1 to 1:3. It was found that the conversion changed with the LA:FA largely; it increased initially with enhancing the molar ratio from 1:1 (63.4%) to 1:2 (91.4%) and then decreased slightly when the ratio reached up to 1:3 (87.1%) [Figure 6C]. Correspondingly, the selectivity for GVL presented a slight increase from 96.0% to 99.2% and 97.3%, respectively. The reaction temperature typically affected the overall reaction rate [Figure 6D]. At 160 °C, the reaction is very inert, with only 3.2% of LA converted. When the temperature was raised, the conversion slightly increased and reached 91.4% at

Figure 6. Catalytic performances of the catalysts of (A) CuAl, NiAl and CuNiAl. Reaction conditions: LA: 5 mmol, N2: 0.1 MPa, FA:LA = 2, catalyst: 50 mg, 1,4-dioxane 20 mL, 6 h, 200 °C. Other products include AL and gas (methane, propane, butane, CO2); (B) Effects of molar ratio of Ni:Cu:Al; (C) molar ratio of LA:FA; (D) reaction temperature on the conversion and selectivity. LA: Levulinic acid; FA: formic acid; AL: angelica lactone.

Stability

For most Cu-based heterogeneous catalysts, although they exhibited high activity, deactivation always occurs in acidic aqueous conditions owing to the active Cu species being easy to grow, leach out and/or being oxidized under acidic conditions. The stability of CuAl and CuNiAl catalysts is evaluated and compared [Figure 7]. The catalytic activity of CuAl catalyst decreased seriously during the recycling, and the conversion lowered to < 40% at the 4th recycle from 100% of the first run. In comparison, the stability of CuNiAl catalyst was improved significantly although the activity presented a decrease during the recycling, but very slow. The conversion did not show obvious change (around 93%-95%) in the first three runs; while it dropped largely from 4th run, it dropped to 77% at 4th run and to 58% at 6th run. It is to be noted that the selectivity to the desired product of GVL was kept at a high level of above 98% without any change during the recycling. The stability of heterogeneous catalysts usually depends closely on the strong interactions of metal-metal or metal-support[33,34] and the surface and electronic properties of catalysts[35-37]. Thus, the decrease of the activity was discussed based on structure analysis by the XRD, TEM, XPS, and ICP characterizations.

Figure 7. Recycling results for CuAl and CuNiAl catalysts in the transfer hydrogenation of LA. LA: 5 mmol, N2: 0.1 MPa, FA:LA = 2, catalyst: 50 mg, 1,4-dioxane 20 mL, 6 h. 200 °C. LA: Levulinic acid; FA: formic acid.

From the results of XRD [Figure 8], for the recycled CuAl catalyst, the intensity of the Cu0 diffraction peak increased, indicating a growth of the Cu particle, which should be the primary reason for its deactivation. By contrast, the intensity of the characteristic diffraction peak of CuNi decreased for the recycled CuNiAl catalyst. The weak diffraction was supposed to be caused by the crystallinity change as the recycled CuNiAl catalyst has been used six times in the acidic aqueous conditions. The results of TEM in Figure 9 showed that the Cu nanoparticles aggregated obviously on the CuAl after four times used. By contrast, the agglomeration was very less for the CuNiAl catalyst after six times used. Thus, the doping of Ni species with the formation of CuNi alloy could prevent the agglomeration of active species.

Figure 8. XRD patterns of the fresh and used CuAl and CuNiAl catalysts, respectively. XRD: X-ray diffraction.

Figure 9. TEM images of (A) fresh CuNiAl and (B) fresh CuAl, and (C) used CuNiAl and (D) used CuAl catalysts. TEM: Transmission electron microscopy.

The used catalysts were also characterized by XPS [Figure 10 and Supplementary Table 2]; the Cu2+/Cu+/0 increased from 0.35 on the fresh NiCuAl to 0.56 on the used NiCuAl for six runs. The change of the Cu2+/Cu0/+ was much more on the CuAl catalyst; it changed from 0.42 to 0.81 after being recycled four times. Moreover, the ICP–AES analysis showed an obvious leaching of Cu occurred for the CuAl catalyst (loss 0.014% Cu) while the leaching was not detected for the CuNiAl catalysts; thus, the Cu leaching and the oxidation of Cu species in the CuNiAl catalyst was prohibited by the formation of CuNi alloy.

Figure 10. Cu 2p XPS spectra of fresh and used catalysts for CuAl and CuNiAl, respectively. XPS: X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy.

Based on the above analysis, it is clear that the overgrowth, leaching and oxidation of Cu species are the main reasons for the deactivation of CuAl catalyst under acidic reaction conditions. However, these phenomena were prohibited as the formation of CuNi alloy on the surface of CuNiAl catalyst; thus, the catalytic stability was improved largely. Moreover, the CuNiAl catalyst showed superior or comparable catalytic performances to the reported catalysts for the liquid or vapor phase transfer hydrogenation of LA to GVL with FA as a hydrogen source [Supplementary Table 3].

Reaction mechanism

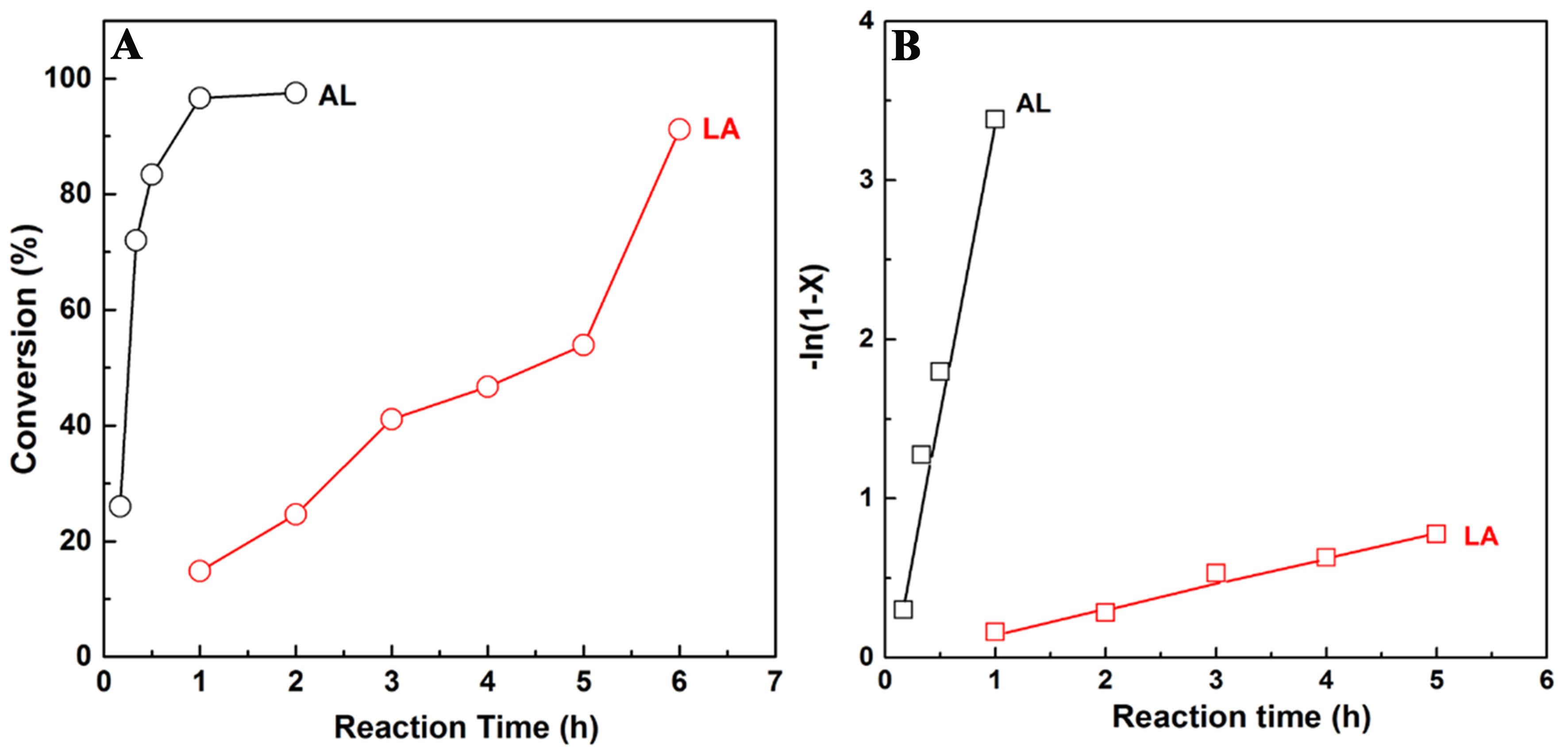

In attempting to better understand the pathway of reaction and catalytic mechanism of LA hydrogenation with FA over the CuNiAl catalyst, the evolution of reactants along with reaction time was performed. The hydrogenation of LA to produce GVL may go with the following steps: One is that LA initially undergoes hydrogenation to an intermediate of 4-hydroxyvaleric acid and then lactonization to GVL; The other is LA dehydration on acid sites to form an intermediate of angelica lactone (AL) and then hydrogenation to GVL. The reaction rate of AL intermediate used as starting substrate on CuNiAl catalyst was examined and compared to that of LA over CuNiAl catalyst. As shown in Figure 11A, it is obvious that a high conversion of AL reached 97.5% while LA conversion was only 25% within 2 h reaction. Moreover, the reaction rate was matched using first-order kinetics according to the reaction results [Figure 11B]. The reaction rate constant to AL is 3.6 h-1, 23 times higher than the rate constant of LA (0.16 h-1). In addition, AL product can be obtained at a low yield over CuNiAl catalyst after 6 h without the addition of FA whereas the conversion of LA was only 10%. The conversion of LA without FA was much lower, indicating the transfer hydrogenation of LA to GVL does not pass through the dehydration of LA to intermediate products of AL and then AL hydrogenation to GVL, but goes through the hydrogenation first and then dehydration. However,

Figure 11. Catalytic activity for LA and AL hydrogenation with FA as a hydrogen donor over the CuNiAl catalyst: (A) conversion vs. reaction time and (B) -ln(1-X) vs. reaction time, where X is the conversion of LA and AL. The R2 values of the fitting results were higher than 98%, confirming the validity of the first-order assumption. LA: Levulinic acid; AL: angelica lactone; FA: formic acid.

On the basis of the results discussed above, a plausible catalytic mechanism for the hydrogenation of LA with FA to produce GVL over CuNiAl catalyst was proposed. As shown in Scheme 1, the Cu active sites synergistically interact with the surface acid sites by first promoting the dissociation of FA to form active H, then hydrogenation and dehydration take place on the active sites of Cu and the surface acid site, respectively. The synergistic effects between Cu active sites and the surface acid sites endowed the catalyst to produce GVL with a high yield. It should be noted that the surface CuNi alloy species played an important role in protecting Cu particles from partial oxidation, aggregation and leaching under acidic reaction conditions; thus, the stability of CuNiAl catalyst was improved significantly.

CONCLUSIONS

An efficient CuNiAl catalyst was synthesized with structural, topological transformation of a LDH precursor. The CuNiAl catalyst exhibited high catalytic activity (100%) and selectivity (97.3%) and the improved stability in the transfer hydrogenation of LA to GVL with FA as the hydrogen donor. The formation of CuNi alloy in the CuNiAl catalyst played an important role in preventing Cu particles from partial oxidation, aggregation and leaching under acidic reaction conditions. Moreover, the synergistic effects between Cu active sites and the surface acid-base on the surface of CuNiAl contribute to the outstanding catalytic performances in the transfer hydrogenation of LA with FA; GVL was produced with a 97.3% high yield.

DECLARATIONS

Authors’ contributions

Investigation, methodology, data curation, writing original draft: Su X

Investigation, formal analysis: Zhou L, Zhang L

Validation, software: Li J, Xiao T

Investigation: Gong Q

Supervision, methodology, funding acquisition, writing-review and editing: Cheng H

Conceptualization, funding acquisition, writing-review and editing: Zhao F

Availability of data and materials

The raw data supporting the findings of this study are available within this Article and its Supplementary Materials. Further data is available from the corresponding authors upon request.

Financial support and sponsorship

We gratefully acknowledge the financial support from the National Key Research and Development Program of China (No. 2022YFA1504901), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 22072142), and the Postdoctoral International Exchange Talent-Introduction Program (No. 2022000226).

Conflicts of interest

All authors declared that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2025.

Supplementary Materials

REFERENCES

2. Stamenkovic, V. R.; Strmcnik, D.; Lopes, P. P.; Markovic, N. M. Energy and fuels from electrochemical interfaces. Nat. Mater. 2016, 16, 57-69.

3. Manzer, L. E. Catalytic synthesis of α-methylene-γ-valerolactone: a biomass-derived acrylic monomer. Appl. Catal. A. Gen. 2004, 272, 249-56.

4. Hengst, K.; Ligthart, D. A. J. M.; Doronkin, D. E.; et al. Continuous synthesis of γ-valerolactone in a trickle-bed reactor over supported nickel catalysts. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2017, 56, 2680-9.

5. Fábos, V.; Mika, L. T.; Horváth, I. T. Selective conversion of levulinic and formic acids to γ-valerolactone with the shvo catalyst. Organometallics 2014, 33, 181-7.

6. Wettstein, S. G.; Alonso, D. M.; Chong, Y.; Dumesic, J. A. Production of levulinic acid and gamma-valerolactone (GVL) from cellulose using GVL as a solvent in biphasic systems. Energy. Environ. Sci. 2012, 5, 8199.

7. Yan, K.; Lafleur, T.; Jarvis, C.; Wu, G. Clean and selective production of γ-valerolactone from biomass-derived levulinic acid catalyzed by recyclable Pd nanoparticle catalyst. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 72, 230-2.

8. Molleti, J.; Tiwari, M. S.; Yadav, G. D. Novel synthesis of Ru/OMS catalyst by solvent-free method: Selective hydrogenation of levulinic acid to γ-valerolactone in aqueous medium and kinetic modelling. Chem. Eng. J. 2018, 334, 2488-99.

9. Siddiqui, N.; Pendem, C.; Goyal, R.; et al. Study of γ-valerolactone production from hydrogenation of levulinic acid over nanostructured Pt-hydrotalcite catalysts at low temperature. Fuel 2022, 323, 124272.

10. Li, W.; Xie, J.; Lin, H.; Zhou, Q. Highly efficient hydrogenation of biomass-derived levulinic acid to

11. Xu, Q.; Li, X.; Pan, T.; et al. Supported copper catalysts for highly efficient hydrogenation of biomass-derived levulinic acid and γ-valerolactone. Green. Chem. 2016, 18, 1287-94.

12. Hengne, A. M.; Rode, C. V. Cu-ZrO2 nanocomposite catalyst for selective hydrogenation of levulinic acid and its ester to γ-valerolactone. Green. Chem. 2012, 14, 1064.

13. Upare, P. P.; Jeong, M.; Hwang, Y. K.; et al. Nickel-promoted copper-silica nanocomposite catalysts for hydrogenation of levulinic acid to lactones using formic acid as a hydrogen feeder. Appl. Catal. A. Gen. 2015, 491, 127-35.

14. Yanase, D.; Hara, T.; Sato, F.; Yamada, Y.; Sato, S. Vapor-phase hydrogenation of levulinic acid to γ-valerolactone over Cu-Ni alloy catalysts. Appl. Catal. A. Gen. 2021, 616, 118093.

15. Yan, K.; Chen, A. Selective hydrogenation of furfural and levulinic acid to biofuels on the ecofriendly Cu-Fe catalyst. Fuel 2014, 115, 101-8.

16. Belguendouz, M. N.; Gancedo, J.; Rapado, P.; et al. Selective synthesis of γ-valerolactone from levulinic and formic acid over ZnAl mixed oxide. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 414, 128902.

17. Dutta, S.; Yu, I. K.; Tsang, D. C.; et al. Green synthesis of gamma-valerolactone (GVL) through hydrogenation of biomass-derived levulinic acid using non-noble metal catalysts: a critical review. Chem. Eng. J. 2019, 372, 992-1006.

18. Gu, X.; Lu, Z. H.; Jiang, H. L.; Akita, T.; Xu, Q. Synergistic catalysis of metal-organic framework-immobilized Au-Pd nanoparticles in dehydrogenation of formic acid for chemical hydrogen storage. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 11822-5.

19. Grasemann, M.; Laurenczy, G. Formic acid as a hydrogen source - recent developments and future trends. Energy. Environ. Sci. 2012, 5, 8171.

20. Singh, A. K.; Singh, S.; Kumar, A. Hydrogen energy future with formic acid: a renewable chemical hydrogen storage system. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2016, 6, 12-40.

21. Soszka, E.; Reijneveld, H. M.; Jędrzejczyk, M.; Rzeźnicka, I.; Grams, J.; Ruppert, A. M. Chlorine influence on palladium doped nickel catalysts in levulinic acid hydrogenation with formic acid as hydrogen source. ACS. Sustainable. Chem. Eng. 2018, 6, 14607-13.

22. Patel, J.; Patel, A. Solvent free hydrogenation of levulinic acid over in-situ generated Ni(0) stabilized by supported phosphomolybdic acid using formic acid as an internal hydrogen source. Renew. Energy. 2022, 201, 190-201.

23. Zhou, Z.; Ng, Y. H.; Xu, S.; et al. A CuNi alloy-carbon layer core-shell catalyst for highly efficient conversion of aqueous formaldehyde to hydrogen at room temperature. ACS. Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2021, 13, 37299-307.

24. Chen, K.; Ling, J. L.; Wu, C. D. In situ generation and stabilization of accessible Cu/Cu2O heterojunctions inside organic frameworks for highly efficient catalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2020, 132, 1941-7.

25. Zhang, Y.; Li, Z.; Zhang, J.; et al. Nanostructured Ni-MoCx: an efficient non-noble metal catalyst for the chemoselective hydrogenation of nitroaromatics. Nano. Res. 2023, 16, 8919-28.

26. Ang, M. L.; Miller, J. T.; Cui, Y.; Mo, L.; Kawi, S. Bimetallic Ni-Cu alloy nanoparticles supported on silica for the water-gas shift reaction: activating surface hydroxyls via enhanced CO adsorption. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2016, 6, 3394-409.

27. Pang, S. H.; Love, N. E.; Medlin, J. W. Synergistic effects of alloying and thiolate modification in furfural hydrogenation over Cu-based catalysts. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2014, 5, 4110-4.

28. Srivastava, S.; Jadeja, G.; Parikh, J. Synergism studies on alumina-supported copper-nickel catalysts towards furfural and

29. Osipova, E. S.; Sedlova, D. V.; Gutsul, E. I.; et al. Reactivity of heterobimetallic ion pairs in formic acid dehydrogenation. Organometallics 2023, 42, 2651-60.

30. Ge, H.; Jing, Y.; Yang, X. Computational design of cobalt catalysts for hydrogenation of carbon dioxide and dehydrogenation of formic acid. Inorg. Chem. 2016, 55, 12179-84.

31. Bielinski, E. A.; Lagaditis, P. O.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Lewis acid-assisted formic acid dehydrogenation using a pincer-supported iron catalyst. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 10234-7.

32. Gong, Z.; Narayana, Y. S.; Lin, Y.; et al. Rational synthesis of ruthenium-based metallo-supramolecular polymers as heterogeneous catalysts for catalytic transfer hydrogenation of carbonyl compounds. Appl. Catal. B. Environ. 2022, 312, 121383.

33. Lunkenbein, T.; Schumann, J.; Behrens, M.; Schlögl, R.; Willinger, M. G. Formation of a ZnO overlayer in industrial Cu/ZnO/Al2O3 catalysts induced by strong metal-support interactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2015, 127, 4627-31.

34. Xu, M.; Yao, S.; Rao, D.; et al. Insights into interfacial synergistic catalysis over Ni@TiO2-x catalyst toward water-gas shift reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 11241-51.

35. Ro, I.; Resasco, J.; Christopher, P. Approaches for understanding and controlling interfacial effects in oxide-supported metal catalysts. ACS. Catal. 2018, 8, 7368-87.

36. Wang, L.; Zhang, J.; Zhu, Y.; et al. Strong metal-support interactions achieved by hydroxide-to-oxide support transformation for preparation of sinter-resistant gold nanoparticle catalysts. ACS. Catal. 2017, 7, 7461-5.

Cite This Article

How to Cite

Su, X.; Zhou, L.; Zhang, L.; Li, J.; Xiao, T.; Gong, Q.; Cheng, H.; Zhao, F. The transfer hydrogenation of levulinic acid to γ-valerolactone over CuNiAl catalyst. Chem. Synth. 2025, 5, 16. http://dx.doi.org/10.20517/cs.2024.30

Download Citation

Export Citation File:

Type of Import

Tips on Downloading Citation

Citation Manager File Format

Type of Import

Direct Import: When the Direct Import option is selected (the default state), a dialogue box will give you the option to Save or Open the downloaded citation data. Choosing Open will either launch your citation manager or give you a choice of applications with which to use the metadata. The Save option saves the file locally for later use.

Indirect Import: When the Indirect Import option is selected, the metadata is displayed and may be copied and pasted as needed.

About This Article

Special Issue

Copyright

Data & Comments

Data

Comments

Comments must be written in English. Spam, offensive content, impersonation, and private information will not be permitted. If any comment is reported and identified as inappropriate content by OAE staff, the comment will be removed without notice. If you have any queries or need any help, please contact us at support@oaepublish.com.