Rewiring the tumor microenvironment in hepatocellular carcinoma: mechanism-driven integration of immunotherapy and locoregional strategies

Abstract

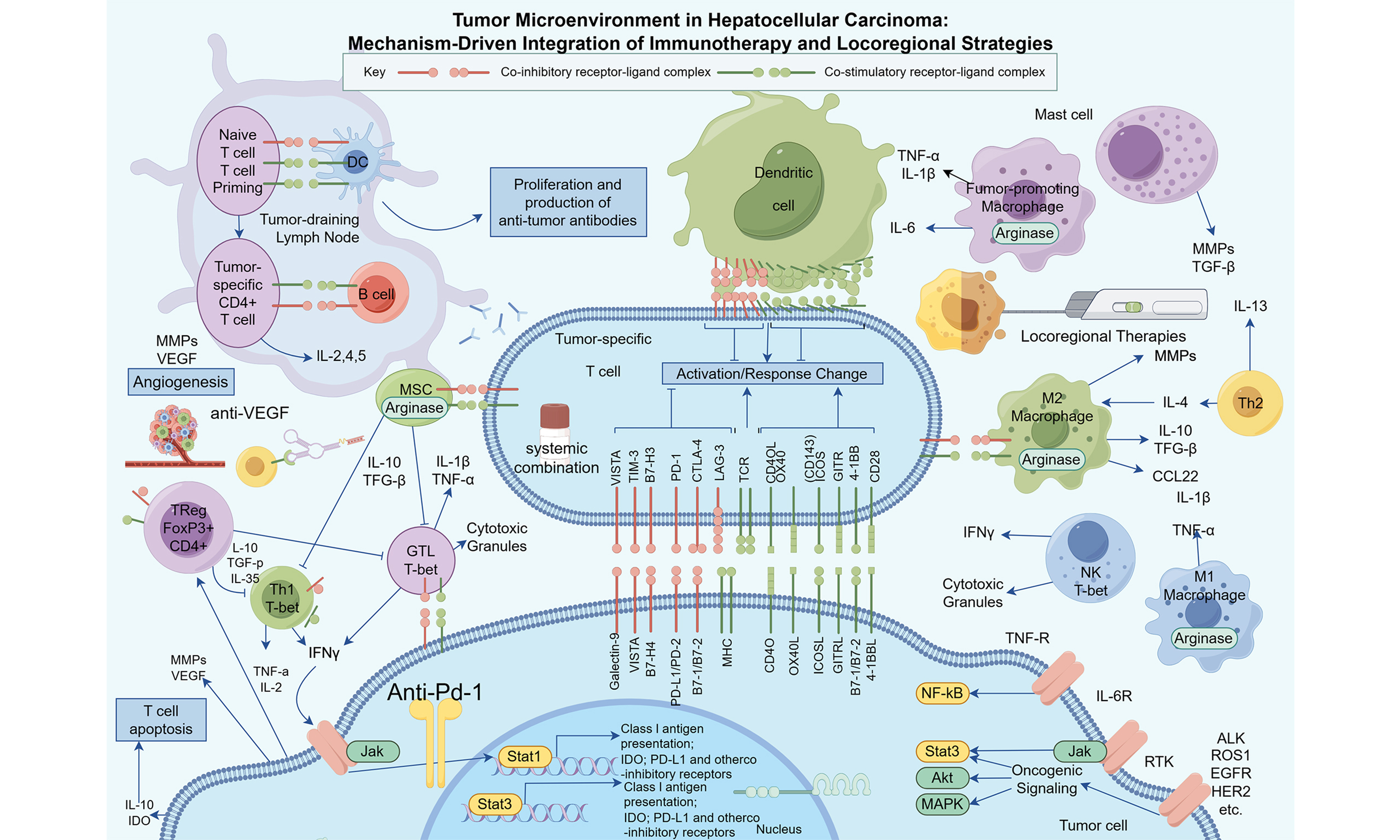

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) arises in a cirrhotic, tolerogenic liver and within a heterogeneous tumor microenvironment (TME) that constrains the efficacy of single-agent systemic therapy. Although immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) and anti-angiogenic drugs have enhanced results, clinicians still lack a mechanistic framework to match specific combinations and locoregional therapies to distinct TME states or disease stages. Here, we synthesize late-phase clinical trial data and experimental studies to link three dominant TME phenotypes - inflamed, immune excluded and immune desert - to first-line ICI-based

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

The unabating global burden of hepatocellular carcinoma

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) remains a significant challenge to global public health. The latest Global Cancer Statistics (GLOBOCAN) 2022 estimate, released by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), reported liver cancer as the 6th most commonly diagnosed cancer type worldwide, with approximately 866,136 newly diagnosed cases in 2020[1], and the 3rd leading cause of cancer-related deaths, with 758,725 deaths in 2020. These statistics present a sobering reality: a high percentage of patients will die from the disease, indicating an urgent and unmet medical need for effective treatments.

HCC is a geographically heterogeneous disease with the highest rates of occurrence limited to Eastern Asia, Northern Africa and Micronesia, with a dramatic difference in burden in Mongolia than in other countries[2]. This distribution is dominated by the epidemiology of underlying risk factors, predominantly chronic infections with hepatitis B virus (HBV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV), alcoholic liver disease, and the emerging epidemic of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MASH)[3]. These data provide another important facet of global health inequity. The analysis of the mortality-to-incidence ratio (MIR), a measure of cancer fatality, shows a negative correlation with the Human Development Index (HDI). This suggests that HCC patients residing in low-HDI countries face significantly higher mortality following diagnosis, most likely due to late-stage presentation, limited availability or access to advanced screening and diagnostic techniques, and lack of treatment with newer, more effective therapies. This gap is likely to grow: an IARC report foresees that 77% of new cases will occur by 2050, most strongly in low- and medium-HDI countries with the weakest healthcare systems to address the growing burden. In the face of this global, lethal, and inequitably distributed disease, the development and dissemination of more effective therapeutic approaches is already essential.

The historical context: a decade of stagnation in the sorafenib era

Treatment for patients with advanced, unresectable HCC was limited for over a decade to a single agent, sorafenib. This multi-kinase inhibitor, which targets the vascular endothelial growth factor receptor (VEGFR) and other signaling pathways, demonstrated for the first time that a systemic agent could improve survival in this setting[4]. This improvement was modest, with only an addition of a few months of median overall survival (OS). Significant numbers of patients either gained only marginal clinical benefit or suffered major treatment-related toxicities that negatively affected their quality of life[4,5]. A lengthy era of therapeutic stagnation ensued in which many clinical trials of alternative therapies failed to show any advantage over the introduction of sorafenib[4,5]. This slow-moving landscape highlighted the complex biological milieu and the notoriously unresponsive nature of HCC, underscoring the urgent need for change.

The modern paradigm: rationale for combination and multi-modal therapies

The emergence of immunotherapy - i.e., immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) - brought a paradigm shift in the treatment of HCC and other cancers[6]. Early investigations into ICI monotherapy targeting programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1), such as nivolumab and pembrolizumab, provided an essential proof of concept. These agents demonstrated the ability to elicit durable responses in a proportion of patients, confirming the efficacy of leveraging the patient’s own immune system to treat the disease[7]. However, overall monotherapy response rates remained modest, highlighting the profoundly immunosuppressive HCC tumor microenvironment (TME)[8].

This realization triggered significant efforts in investigating combination strategies aimed at overcoming primary and acquired resistance to immunotherapy. The current state-of-the-art in HCC therapy reflects a deeper comprehension of the TME. The limited efficacy of ICI monotherapy indicated that the HCC TME is not only non-inflamed but actively resistant to a robust anti-tumor immune response[9,10]. A large part of this immunosuppression is due to the overexpression of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), driving not only aberrant angiogenesis but also directly disabling the immune system by blocking dendritic cell maturation and T-cell infiltration[11]. This mechanistic insight serves as the conceptual foundation of the current treatment paradigm, giving rise to two pillars of combination therapy. The first involves combining systemic agents - such as dual immune checkpoint inhibition or ICIs with anti-angiogenic agents - to achieve more potent synergistic anti-tumor effects. The second combines highly effective systemic drugs with traditional locoregional treatments (LRTs), including transarterial chemoembolization (TACE), radiotherapy (RT), and ablation[12]. Compelling arguments for this convergence revolve around the fact that LRTs can induce immunogenic cell death. This process releases a surge of tumor antigens and inflammatory signals into the bloodstream, priming a systemic anti-tumor immune response that is subsequently expanded and sustained by the effects of ICIs. This comprehensive review will address these paradigm-shifting advances that are collectively remapping the therapeutic algorithm and improving survival for patients with HCC.

THE NEW ERA OF FIRST-LINE SYSTEMIC THERAPY IN ADVANCED HCC

The management of advanced HCC has been radically altered by the success of combination regimens, which have proven significantly superior to sorafenib monotherapy. These strategies have rapidly become the new standard of care, primarily relying on an ICI in combination with an anti-angiogenic agent or another ICI. The therapeutic landscape is no longer homogeneous but has instead become fragmented by mechanistically distinct approaches; thus, the implementation of biomarker-driven patient selection is essential to maximize clinical benefit.

The foundational combination: anti-VEGF and anti-PD-L1 blockade

The landmark IMbrave150 trial: atezolizumab and bevacizumab

The approval and widespread adoption of the combination of atezolizumab, a monoclonal antibody targeting programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1), and bevacizumab, a monoclonal antibody targeting VEGF-A, represents arguably the most significant breakthrough in the systemic management of HCC in over a decade[13]. The Phase III IMbrave150 trial (NCT03434379) was a pivotal, practice-changing study that directly compared atezolizumab plus bevacizumab (Atezo + Bev) against sorafenib in patients with unresectable HCC who had not received prior systemic therapy[14].

The updated OS and progression-free survival (PFS) analysis, with a median follow-up of 8.6 months, showed a statistically significant and clinically meaningful difference in both dual primary endpoints: OS [hazard ratio (HR), 0.58; 95% confidence interval (CI), 0.42-0.79; P < 0.001] and PFS (HR 0.59; 95%CI: 0.47-0.79; P < 0.001) in the combination arm. A later analysis with a median follow-up of 15.6 months confirmed that this benefit was durable. A median OS of 19.2 months was reported for the combination, compared to 13.4 months for the sorafenib arm (HR 0.66; 95%CI: 0.52-0.85). At 18 months, the survival rate was 52% with the combination vs. 40% with sorafenib, highlighting a sustained treatment effect[14]. In addition, the confirmed objective response rate (ORR) per Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) 1.1 was 29.8% in the combination arm, compared to a markedly lower rate in the sorafenib arm. Interestingly, the updated analysis reported a 7.7% complete response (CR) rate, suggesting substantial and prolonged tumor regression in a significant proportion of patients[15]. Consequently, this landmark trial established Atezo + Bev as a new global first-line standard of care, which has since been endorsed by major international treatment guidelines.

Biological synergy: unpacking the VEGF-immunity axis

The profound success of the Atezo + Bev combination is rooted in the strong biological synergy between PD-L1 blockade and VEGF inhibition[16]. The HCC TME is often characterized by hypoxia and high levels of VEGF, which not only promotes the formation of a tortuous and dysfunctional tumor vasculature but also exerts potent and multifaceted immunosuppressive effects[17]. VEGF directly inhibits the maturation of dendritic cells, the professional antigen-presenting cells (APCs) required to initiate an anti-tumor T-cell response. It also promotes the infiltration and expansion of immunosuppressive cell populations, including regulatory T cells (Tregs) and myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs), which actively dampen immune activity. Critically, VEGF impairs the trafficking of cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) into the tumor bed and compromises the function of those that do manage to infiltrate[18].

By binding to VEGF-A, bevacizumab reverses this immunosuppressive environment through the “normalization” of the tumor vasculature. This process renders the vessels less permeable and better able to support the infiltration of effector T cells[19]. Simultaneously, atezolizumab inhibits the binding of PD-L1 - upregulated on both tumor and immune cells within the TME - to the PD-1 receptor on activated T cells[20]. This blockade is a crucial driver of the anti-tumor immune response, whereby cytotoxic T cells are unleashed to infiltrate the tumor more effectively, aided by the improved access provided by vascular normalization. Thus, the combination creates a synergy that results in more profound and sustained anti-tumor activity than is achievable with either agent alone.

The rise of dual immune checkpoint blockade

Deviating from the anti-angiogenic backbone, a first-line treatment option involving dual immune checkpoint blockade has been established. This approach targets two separate, non-redundant inhibitory pathways to expand and augment the anti-tumor immune response. Its efficacy has been confirmed by two pivotal Phase III trials, establishing it as another landmark therapeutic modality in advanced HCC.

The HIMALAYA regimen: durvalumab and tremelimumab (STRIDE)

The Phase III HIMALAYA study (NCT03298451) provided the first validation for a non-VEGF inhibitor-based combination in the first-line setting[21]. The trial evaluated the STRIDE (Single Tremelimumab Regular Interval Durvalumab) regimen, which consists of a single priming dose of tremelimumab (an anti-cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 antibody) followed by regular-interval durvalumab (an anti-PD-L1 antibody), and compared it against sorafenib. The study met its primary endpoint, demonstrating that the STRIDE regimen resulted in a statistically significant and clinically meaningful improvement in OS compared to sorafenib (HR 0.78; 95%CI: 0.67-0.92).

The most striking result of the HIMALAYA trial is the persistence of the survival benefit over a prolonged follow-up[22]. In the 4-year analysis, a survival rate of 25.2% was reported for patients treated with the STRIDE regimen, compared to 15.1% for those treated with sorafenib. More recently, a 5-year analysis established a new benchmark for long-term survival: 19.6% for the STRIDE regimen vs. 9.4% for sorafenib. Notably, approximately 20% of patients treated with this dual-immunotherapy regimen remained alive at five years[23]. This regimen is a much-appreciated first-line treatment option, particularly for patients with contraindications to anti-angiogenic therapy, such as those at high risk for bleeding from untreated esophageal varices.

Nivolumab plus ipilimumab: new evidence from the CheckMate 9DW trial (American Society of Clinical Oncology 2024)

The Phase III CheckMate 9DW trial (NCT04039607) evaluated nivolumab (anti-PD-1) plus ipilimumab (anti-CTLA-4) vs. investigator’s choice of tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI; lenvatinib in 85% and sorafenib in 15%) as first-line therapy for unresectable HCC. After a median follow-up of 35.2 months, nivolumab plus ipilimumab significantly improved OS compared with TKIs (median OS: 23.7 months vs. 14.7 months; HR 0.79; 95%CI: 0.65-0.96; P = 0.0180). The ORR was 36% in the nivolumab-ipilimumab arm vs. 13% in the TKI arm, with CR rates of 7% and 2%, respectively. Responses were notably durable, with a median duration of response of 30.4 months for nivolumab-ipilimumab compared with 12.9 months for TKIs. These data establish dual ICI blockade as a highly effective first-line option for advanced HCC, particularly for patients in whom an anti-VEGF backbone is unsuitable or less desirable.

Mechanistic rationale and clinical implications of dual ICI

The dual ICI blockade is effective because it targets two independent and mutually complementary checkpoints. In contrast to PD-1/PD-L1 blockade, which primarily acts within the TME to reinvigorate exhausted CTLs engaged by chronic antigen exposure, CTLA-4 blockade functions at a more proximal stage. Its effects occur predominantly in secondary lymphoid organs, such as lymph nodes[24]. By blocking CTLA-4 on T cells during their initial priming by APCs, agents such as ipilimumab or tremelimumab reduce the T-cell activation threshold, facilitating the priming and proliferation of a broader and more diverse repertoire of tumor-reactive T cells[25]. The two approaches together seek to expand the pool of tumor-specific T-cell “soldiers” and improve their effector function when directed at the tumor to ultimately mount a more complete, more effective anti-tumor attack. The results of HIMALAYA and CheckMate 9DW trials establish that combination targeting multiple immune pathways is a promising approach for at least a subset of advanced HCC patients, adding one more useful option to the therapeutic menu. These observations align with recent work showing that priming a vascular-selective cytokine response can permit CD8+ T-cell entry into tumors and synergize with dual checkpoint blockade[26].

TKIs paired with immunotherapy: a story of nuance

Following the success of combining immunotherapy with the anti-VEGF antibody bevacizumab, a major subsequent direction of investigation has been the pairing of ICIs with multi-targeted TKIs, many of which inhibit VEGFR in addition to other oncogenic signaling pathways.

Lenvatinib and pembrolizumab: from promise to a re-evaluation

Lenvatinib, a TKI that inhibits VEGFR1-3 and FGFR1-4, as well as other kinases, combined with the anti-PD-1 antibody pembrolizumab, emerged as a highly attractive first-line regimen. The Phase Ib KEYNOTE-524 study (NCT03006926) demonstrated outstanding efficacy and an acceptable safety profile, including a high ORR, leading to accelerated approval in certain regions[27]. The rationale was analogous to that of the Atezo + Bev combination; it was speculated that lenvatinib’s potent anti-angiogenic activity would remodel the TME, making it more receptive to the immune-potentiating effects of pembrolizumab.

However, the definitive Phase III LEAP-002 trial (NCT03713593), designed to confirm the superiority of lenvatinib plus pembrolizumab vs. lenvatinib plus placebo, yielded a surprising and highly informative result. The study did not meet its dual primary endpoints of OS and PFS[28]. The final analysis revealed a median OS of 21.2 months for the combination arm vs. an unexpectedly long 19.0 months for the lenvatinib monotherapy arm (HR 0.84; 95%CI: 0.71-0.98; P = 0.0227); this result did not cross the pre-specified boundary for statistical significance. Long-term follow-up data confirmed this trend, with a median OS of 21.1 months vs. 19.0 months (HR 0.80).

The “failure” of LEAP-002 is perhaps the most impactful result in recent HCC research, recalibrating our understanding of lenvatinib monotherapy and the challenge of achieving a survival benefit[29]. The combination arm performed excellently, delivering one of the longest median survival durations recorded in a Phase III HCC trial. The unexpected result was the robust performance of the control arm; the 19.0 month median OS for lenvatinib monotherapy is significantly longer than the 13.6 months observed in the REFLECT trial (NCT01761266) that led to its initial approval. This indicates improved patient management, better supportive care, and the availability of effective subsequent lines of therapy. In fact, lenvatinib monotherapy has emerged as a much more effective backbone than previously recognized. Consequently, the outcome of LEAP-002 suggests not that the combination is ineffective, but that the incremental benefit of adding pembrolizumab to a highly active, modern TKI baseline is marginal and difficult to detect statistically[30]. This finding has important implications: it raises the threshold for future TKI-ICI trials and reaffirms lenvatinib monotherapy as a robust standard-of-care comparator.

Other TKI-ICI combinations

In addition to lenvatinib and pembrolizumab, other TKI-ICI combinations have proved promising, establishing this pairing as a leading strategy in contemporary HCC management. The combination of the anti-PD-1 antibody camrelizumab with the VEGFR2-selective TKI rivoceranib (also known as apatinib) demonstrated a favorable OS in the Phase III CARES-310 study (NCT03764293) conducted primarily in a Chinese population, leading to its approval in that region[28]. This wealth of data suggests a clear and unequivocal trend: the strategy of potentiating a TKI with an ICI is a robust and flexible approach that remarkably increases survival for patients with advanced-stage HCC [Table 1].

Pivotal phase III trials in first-line systemic therapy for advanced HCC

| Trial name (Regimen) | Control arm | N | Median OS (months) | OS HR (95%CI) | Median PFS (months) | ORR (%) | CR (%) | Median DOR (months) |

| IMbrave150 (Atezo + Bev) | Sorafenib | 501 | 19.2 | 0.66 (0.52-0.85) | 6.9 | 29.8 | 7.7 | 18.1 |

| HIMALAYA (Durva + Treme) | Sorafenib | 1,171 | 16.4 | 0.78 (0.67-0.92) | 3.8 | 20.1 | N/A | 22.3 |

| CheckMate 9DW (Nivo + Ipi) | Lenvatinib/Sorafenib | 668 | 23.7 | 0.79 (0.65-0.96) | 9.1* | 36 | 7 | 30.4 |

| LEAP-002 (Lenva + Pembro) | Lenvatinib + Placebo | 794 | 21.2 | 0.84 (0.71-0.98)† | 8.2 | 26.1 | 2.5 | 16.6 |

Taken together, VEGF-driven angiogenesis and immune suppression, cyclic guanosine monophosphate-adenosine monophosphate synthase (cGAS)-stimulator of interferon genes (STING)-mediated innate sensing, and β-catenin-mediated immune exclusion delineate three major TME axes that shape response to systemic therapy. These axes map onto inflamed, immune-excluded and immune-desert phenotypes, providing a conceptual framework for choosing between anti-PD-L1/anti-VEGF combinations, dual ICI, and TKI-anchored regimens.

INTEGRATING LOCOREGIONAL AND SYSTEMIC THERAPIES: A SYNERGISTIC APPROACH

Despite the recent impact of systemic therapy in treating advanced disease, a large portion of HCC patients are diagnosed in intermediate-stage disease (Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer stage B), for which LRTs have long served as the standard of care. The next significant development in the treatment of HCC is the organized use of very effective systemic agents in conjunction with LRTs to better treat patients across the intermediate and advanced stage spectrum. The basic idea is that locoregional control of tumor can establish an immunologically “hot” microenvironment that can be leveraged by systemic immunotherapy.

TACE-plus: validating a new standard for intermediate-stage HCC

TACE is the cornerstone of treatment for patients with intermediate-stage HCC who are not candidates for curative therapies[35]. While effective, TACE responses are often incomplete, and recurrence is common. The combination of TACE with systemic therapies is a highly promising strategy to improve upon these outcomes, and recent Phase III data have validated this approach.

Rationale: TACE as an in situ vaccine

There is a strong biological rationale for combining TACE with systemic therapy. The efficacy of TACE lies in administering chemotherapeutic agents and embolic particles via the tumor-feeding arteries in a manner that introduces a cytotoxic insult and induces ischemic necrosis[36]. Moreover, embolization-induced hypoxia is known to upregulate VEGF expression, making a compelling case for combining anti-angiogenic agents to mitigate this pro-tumorigenic signal. We further believe that the recent clinical success in this space in Phase III trials underscores the need for a triple-therapy approach of TACE + an ICI + an anti-angiogenic agent to yield the best possible benefit. TACE delivers chemotherapeutic agents and embolic material selectively into the tumor-feeding arteries, inducing combined cytotoxic and ischemic necrosis. The resulting tumor cell death releases tumor-associated antigens and damage-associated molecular patterns, which can initiate local immune priming, while embolization-induced hypoxia upregulates VEGF and can drive pro-angiogenic rebound. These features provide a strong biological rationale for combining TACE with both ICIs and anti-VEGF therapy in “TACE-plus” regimens.

EMERALD-1: TACE with durvalumab plus bevacizumab (American Society of Clinical Oncology GI 2024)

The Phase III EMERALD-1 trial (NCT03778957) was a global, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study evaluating the efficacy of TACE combined with durvalumab and bevacizumab in patients with embolization-eligible unresectable HCC. The study met its primary endpoint, demonstrating that the combination of TACE with durvalumab and bevacizumab significantly improved PFS compared to TACE alone (median PFS: 15.0 months vs. 8.2 months; HR 0.77; 95%CI: 0.61-0.98; P = 0.032)[37]. This is the first global Phase III trial to show a positive outcome for systemic therapy combined with TACE. These results may establish a potential new standard of care for patients with intermediate-stage HCC.

The EMERALD-1 trial (NCT03778957) was the first global Phase III study to demonstrate the benefit of adding an ICI-based combination to TACE[37]. The trial enrolled patients with embolization-eligible, unresectable HCC and randomized them to one of three arms: TACE plus durvalumab and bevacizumab (TACE + Durva + Bev); TACE plus durvalumab and placebo; or TACE plus dual placebo.

The study met its primary endpoint, demonstrating that the triple combination of TACE + Durva + Bev significantly improved PFS compared to TACE alone. Median PFS was 15.0 months in the triple-therapy arm vs. 8.2 months in the TACE-alone arm, corresponding to a 23% reduction in the risk of progression or death (HR 0.77; 95%CI: 0.61-0.98; P = 0.032)[37]. The ORR was also highest in the triple-therapy arm at 43.6%, compared to 29.6% for TACE alone[37]. A crucial finding of the trial was that the secondary endpoint comparing TACE plus durvalumab to TACE alone was not met (median PFS 10.0 months; HR 0.94), indicating that the addition of an ICI alone was insufficient to improve outcomes. This strongly suggests that simultaneous blockade of the VEGF pathway with bevacizumab was essential for the combination’s success. The safety profile was manageable, with Grade 3 or 4 treatment-related adverse events (TRAEs) occurring in 32.5% of patients in the triple-therapy arm vs. 13.5% in the TACE-alone arm.

The LEAP-012 trial: TACE with lenvatinib and pembrolizumab

Shortly after the EMERALD-1 results, the Phase III LEAP-012 trial (NCT04246177) provided further validation for the TACE-plus concept, using a different systemic backbone. This study compared TACE plus the combination of lenvatinib and pembrolizumab vs. TACE plus dual placebo in patients with unresectable, non-metastatic HCC[38].

The trial also met its primary endpoint for PFS. At the first interim analysis, the combination of TACE + lenvatinib + pembrolizumab demonstrated a statistically significant and clinically meaningful improvement, with a median PFS of 14.6 months compared to 10.0 months for TACE plus placebo (HR 0.66; 95%CI: 0.51-0.84; one-sided P = 0.0002). The ORR was also significantly higher in the combination arm (47%) vs. the placebo arm (33%). A trend toward improved OS was observed (HR 0.80), but the data were not yet mature and did not reach statistical significance at the time of analysis[25]. While highly effective, this regimen was associated with a higher rate of toxicity. Grade 3 or worse TRAEs occurred in 71% of participants in the combination group, compared to 32% in the placebo group, with hypertension and decreased platelet count being the most common.

The positive results from both EMERALD-1 and LEAP-012 herald the arrival of the TACE-plus era, establishing a new standard of care for eligible patients with intermediate-stage HCC. Data from EMERALD-1, in particular, suggest that a triple-modality approach targeting local disease (TACE), the PD-1/PD-L1 axis (ICI), and the VEGF pathway (anti-angiogenic) is required to unlock the full synergistic potential of this strategy [Table 2].

Key phase III trials combining TACE with systemic therapy

| Trial name (Regimen) | Control arm | N | Primary endpoint | Median PFS (months) | PFS HR (95%CI) | Key secondary endpoints (ORR, OS trend) | Grade 3/4 TRAEs (%) |

| EMERALD-1 (TACE + Durva + Bev) | TACE + Placebo | 409 (204 vs. 205) | PFS | 15.0 vs. 8.2 | 0.77 (0.61-0.98) | ORR: 43.6% vs. 29.6%; OS immature | 32.5 |

| LEAP-012 (TACE + Lenva + Pembro) | TACE + Placebo | 480 (237 vs. 243) | PFS | 14.6 vs. 10.0 | 0.66 (0.51-0.84) | ORR: 47% vs. 33%; OS trend HR 0.80 | 71.3 |

Radiotherapy and immunotherapy: a potent immunomodulatory alliance

The combination of RT and immunotherapy is one of the most exciting areas in contemporary oncology research, with a particularly strong rationale in HCC[4]. Historically viewed as a purely local cytotoxic modality, radiation is now recognized as a potent in situ immunomodulator capable of synergizing effectively with ICIs.

The abscopal effect and the role of stereotactic body radiation therapy

In effect, high-dose irradiation in the institutional review board (IRB) experiment demonstrated the abscopal effect. However, since most clinical treatments are delivered using stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT), and evidence suggests that the abscopal effect does not occur with low-dose-rate, fractionated irradiation, we infer from our single-proton machine experiment that SBRT may be more effective, based on the observed effects[40].

A fascinating demonstration of the immune-enhancing action of RT is the so-called “abscopal effect”, an intriguing, albeit documented, phenomenon in which irradiation of a single tumor lesion induces regression of distant, non-irradiated metastases in some cancer patients, likely mediated by a systemic anti-tumor immune response activated by local irradiation and additional immunotherapy. SBRT, in which high-dose, ablative RT is administered with a high degree of precision, can be a suitable candidate for this approach. Because SBRT induces robust tumor cell death and antigen release, it can serve as a more potent inducer of an immune reaction than conventionally fractionated RT. Evidence from clinical studies consistently demonstrates that RT in combination with ICIs is feasible and tolerable and may result in improved outcomes, with increasing evidence suggesting that concurrent, rather than sequential, administration of ICIs may be more effective.

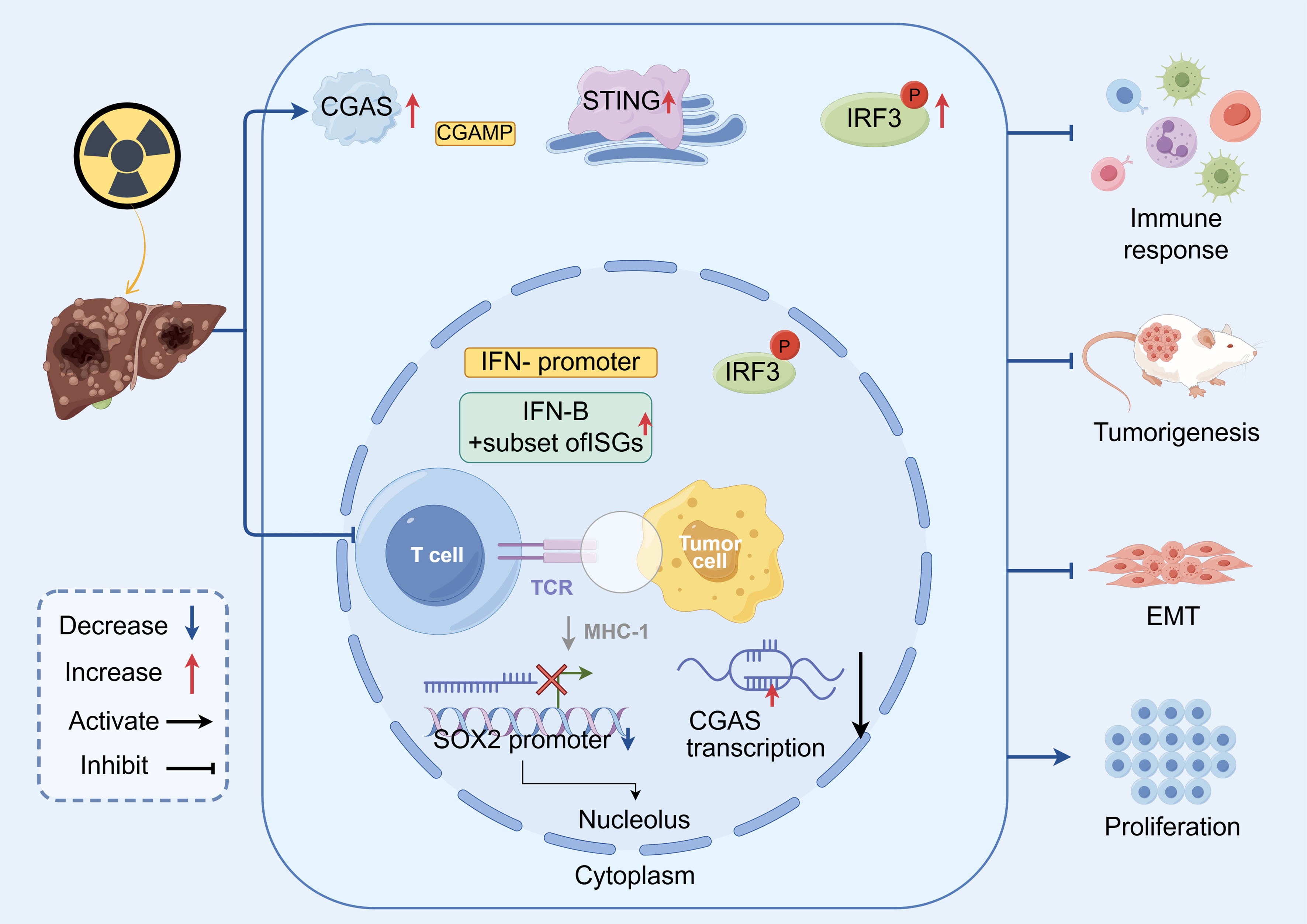

Mechanistic insights: the critical role of the cGAS-STING pathway

The molecular machinery that responds to local radiation damage to activate a systemic immune response is increasingly well characterized, with the cGAS-STING pathway described as the central mechanistic hub, now considered an essential connector between innate and adaptive immunity[41]. The initial event, DNA damage induced by irradiation, leads to an increase in micronuclei, and double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) is released into the cytoplasm of not only tumor cells but also infiltrating APCs, such as dendritic cells[42,43].

Cyclic GMP-AMP (cGAMP) is synthesized by and bound to the cytosolic dsDNA-sensing enzyme cGAS. Subsequently, cGAMP binds and activates STING, an adaptor protein located on the endoplasmic reticulum. Activated STING translocates to the Golgi and triggers a signaling cascade involving TBK1 (TANK-binding kinase 1), which phosphorylates the interferon regulatory transcription factor IRF3. Phosphorylated IRF3 dimerizes and translocates to the nucleus, where it induces the transcription and robust production of type I interferons (IFNs). Type I IFNs are cytokines with multiple pleiotropic effects that play a pivotal role in driving a pro-tumoricidal immune response. They enhance antigen presentation by upregulating major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I molecules on tumor cells, promote dendritic cell maturation and activation, and facilitate recruitment and activation of CD8+ T cells for cytotoxicity, thereby converting an immunologically “cold” tumor into a “hot” tumor that is more sensitive to ICI treatment[44]. This nuanced mechanistic insight has shifted RT from a tool of simple tumor debulking to a systemic immune-priming modality, providing a rational foundation for designing new RT-immunotherapy combination trials. In HCC, RT-induced cGAS-STING activation not only drives local type I interferon production but also conditions the tumor vasculature and myeloid compartment toward a more permissive, T-cell-inflamed state. This establishes a mechanistic bridge between high-dose stereotactic body RT and enhanced responses to PD-1/PD-L1 blockade, supporting combination strategies that exploit RT as an in situ vaccine and cGAS-STING as the conduit from local damage to systemic adaptive immunity. These steps are summarized schematically in Figure 1, which illustrates how cGAS-STING activation links local DNA damage to systemic antitumor immunity in HCC.

Figure 1. Schematic representation of the cGAS-STING pathway as a mechanistic bridge between radiotherapy and systemic antitumor immunity in HCC. cGAS: Cyclic GMP-AMP synthase; cGAMP: cyclic GMP-AMP; STING: stimulator of interferon genes; IRF3: interferon regulatory factor 3; p-IRF3: phosphorylated interferon regulatory factor 3; IFN: interferon; IFN-β: interferon beta; ISGs: interferon-stimulated genes; TCR: T-cell receptor; MHC-I: major histocompatibility complex class I; EMT: epithelial-mesenchymal transition; SOX2: SRY-box transcription factor 2; HCC: hepatocellular carcinoma.

Ablation, HAIC, and TARE in combination with systemic agents

The concept of harnessing in situ tumor destruction to prime a systemic anti-tumor immune response applies equally to other LRTs. Local ablative therapies such as Radiofrequency Ablation (RFA) and Microwave Ablation (MWA) can induce similar in situ tumor destruction and inflammation, which can act as a signal to initiate an anti-tumor immune response[45]. In this context, combining local ablation with systemic immunotherapy makes sense to maximize the beneficial effects of each treatment, with the goal of reducing the risk of local and distant recurrence by enhancing residual immune priming.

Other liver-directed therapies are also being used in conjunction with systemic therapies. Hepatic artery infusion chemotherapy (HAIC), in which chemotherapy is directly administered to the liver at high doses via the hepatic artery, has been combined with ICIs and/or TKIs with remarkable effect, reducing large unresectable or bilobar tumors - patients who are almost invariably non-responsive to other therapies - to a resectable state. Transarterial radioembolization (TARE), which utilizes yttrium-90 microspheres for internal radiation, has been shown to improve survival in unresectable HCC patients when combined with immunotherapy[46]. The common thread of all these combinations is that local and systemic therapies are not mutually exclusive but rather highly synergistic, and their intelligent integration is an essential cornerstone for ensuring optimal patient outcomes in the modern era of HCC care.

EXPANDING THE BOUNDARIES: NEOADJUVANT AND CONVERSION THERAPY

Given the significant impact of modern combination treatments, their use in earlier phases of disease - in the neoadjuvant (preoperative) and conversion therapy settings - has been explored. This represents a major paradigm shift in HCC treatment objectives, moving away from merely controlling disease toward actively increasing the proportion of patients who are potentially curable. The interface between palliative and curative-intent treatment was previously inflexible and could be clearly defined by staging at diagnosis. However, the high response rates observed with newer combination therapies are beginning to blur this line, enabling the use of systemic therapy as a bridge to ultimately curative management.

Conversion therapy: creating a pathway to curative resection

Conversion therapy is the administration of systemic and/or locoregional therapies aimed at downstaging unresectable tumors to achieve curative resection or liver transplantation[47]. It can provide a curative opportunity for patients previously considered palliative. Considering the high ORRs achieved with combination Atezo + Bev or TKI-ICI regimens, these therapies are good candidates for such an application[16]. For example, combination therapy with the TKI cabozantinib and the ICI nivolumab has been shown to be effective in downstaging HCC[48,49] to a resectable state. High-dose combination therapies involving HAIC, TKIs, and ICIs have also demonstrated remarkable results in converting patients with massive, initially unresectable HCC to resectable. Such an approach positions surgery both as a potential therapeutic option and as a means to increase the likelihood of successful liver transplantation by reducing tumor burden to a level compatible with available organ allocation.

Neoadjuvant immunotherapy: targeting micrometastatic disease

Despite therapy, even HCC patients with a resectable presentation still have persistently elevated recurrence rates due to unappreciated micrometastatic disease. Treatment before surgery (neoadjuvant therapy) represents an ideal approach to addressing this problem[50]. Systemic therapy, particularly combinatorial immunotherapy, is a rational strategy to pretreat HCC before surgery and offers several advantages. It has the potential to shrink the primary tumor, making its removal technically less challenging and safer. Of greater importance, it opens a crucial immunological “window of opportunity” to also target micrometastases throughout the body while the immune system is still exposed to the complete set of antigens from the primary tumor in situ. This approach may induce a stronger and broader T-cell response than adjuvant therapy administered after the tumor - the main antigen source - has been removed.

Multiple studies have now demonstrated that neoadjuvant immunotherapy, both as monotherapy and in combination, is safe, feasible, and highly active in patients with resectable HCC[51-53]. Seminal studies using preoperative combinations such as nivolumab plus ipilimumab or lenvatinib plus nivolumab have shown high rates of pathological response, with a significant proportion of patients achieving a major or complete pathological response (pCR) in the resected specimen[53,54]. A strong pathological response to neoadjuvant therapy is increasingly recognized as a powerful surrogate marker for improved long-term outcomes, including recurrence-free and OS. This approach is rapidly gaining traction and has the potential to become a new standard of care for patients with resectable HCC at high risk of recurrence.

FUTURE HORIZONS: EMERGING THERAPIES AND PREDICTIVE BIOMARKERS

As the HCC treatment armamentarium expands at a rapid pace, the front line of research is on the verge of new therapeutic avenues and more biologically informed patient selection. Approaches targeting various niches - such as engineered cells, personalized vaccines, and biomarker-driven therapies that address the underlying causes of therapeutic resistance - rather than relying solely on standard drug discovery, are likely to shape the future of HCC therapy.

Cellular therapies: engineering T-Cells to target HCC

Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy represents a revolutionary advance in cancer treatment, particularly for hematologic malignancies. Its application to solid tumors such as HCC has been challenging, but recent breakthroughs targeting appropriate antigens show considerable promise[55]. A key target that has emerged for HCC is Glypican-3 (GPC3), a cell-surface oncofetal protein that is highly and specifically expressed on the vast majority of HCC cells but is virtually absent in healthy adult tissues, making it an ideal candidate for targeted therapy[56].

Encouraging data have recently been reported at major oncology conferences. The Phase I C-CAR031 study - an “armored” GPC3-specific CAR-T co-developed by AstraZeneca and AbelZeta - in heavily treated advanced HCC patients (median 3.5 prior lines of therapy) has yielded remarkable results, with an ORR of 56.5% across all dose levels vs. 75% in a highly selected, mostly chemo-refractory group [as reported at the 2024 American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) meeting]. Interestingly, the ORR was 0% at the highest dose level (DL4). The disease control rate (DCR) was excellent (91.3%), with tumor regressions observed in both intrahepatic and extrahepatic lesions[57]. Safety was acceptable, with mostly Grade 1 or 2 cytokine release syndrome (CRS) (except in one patient) and no reported ICANS cases. Similarly, preliminary data from another armored GPC3-directed CAR-T product - Runt-related transcription factor 3 (RUNX3)-expressing GPC3 CAR-T cells - show tumor regression in both intrahepatic and extrahepatic lesions of heavily pretreated patients, with an acceptable rate of CRS[58].

Ori-C101 demonstrated a 66% DCR, with all patients at the highest dose achieving an objective response, including one durable CR[59]. These findings suggest that GPC3-targeted CAR-T therapy could become a transformative option for patients who have exhausted standard treatments.

Novel immunotherapeutic targets

While PD-1/PD-L1 and CTLA-4 blockade have become mainstays of treatment, research is actively exploring the next generation of immune checkpoints to overcome resistance.

Beyond PD-1/CTLA-4: the role of TIGIT inhibitors

T-cell immunoglobulin and immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibitory motif domain (TIGIT) has emerged as a key inhibitory receptor expressed on activated T cells and natural killer (NK) cells[60]. When TIGIT binds to its ligand CD155 on tumor cells or APCs, it acts as another immune “brake”, suppressing T-cell and NK-cell function[39]. Preclinical studies have shown that TIGIT and PD-1 pathways can act synergistically to suppress anti-tumor immunity, suggesting that dual blockade could be more effective than blocking either pathway alone[37].

This hypothesis is now being tested in the clinic. The Phase II MORPHEUS-Liver study (NCT04524871) provided important proof-of-concept[61,62]. In this trial, adding the anti-TIGIT antibody tiragolumab to the standard-of-care backbone of atezolizumab and bevacizumab resulted in improved tumor responses compared to the Atezo + Bev doublet alone in first-line unresectable HCC[40]. These encouraging findings have validated the safety and potential efficacy of this triplet combination and have paved the way for larger, confirmatory trials. For example, a Phase II trial (NCT06349980) is currently underway to evaluate the triplet of serplulimab (anti-PD-1), bevacizumab, and the anti-TIGIT fusion protein HLX53 in the first-line setting for advanced HCC[63].

Beyond tiragolumab, several anti-TIGIT antibodies (including ociperlimab, vibostolimab and domvanalimab) are in Phase I-II development in solid tumors, with HCC-specific data still limited. Parallel efforts target other co-inhibitory receptors such as LAG-3 and TIM-3, as well as costimulatory receptors such as OX40 [tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily member 4 (also known as CD134)], and immunosuppressive cytokine pathways including transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β). Although most clinical evidence comes from non-HCC populations, these agents are conceptually attractive for combination with PD-1/PD-L1 blockade in immune-excluded or immune-desert HCC, and future trials will need to define their safety and incremental benefit in cirrhotic patients.

Therapeutic vaccines: a personalized approach

The development of a more customized, so-called neoantigen-based immunotherapy, in the form of cancer vaccines, is now becoming a realistic possibility. Cancer cells harbor more mutations than any other cell type in the body, and some of these mutations give rise to novel peptide structures (“neoantigens”) expressed on the cell surface, which are absent in healthy cells and thus represent foreign antigen targets for the immune system. This approach involves first sequencing the patient’s tumor, using bioinformatics tools to predict which neoantigens are most immunogenic, and subsequently producing a personalized vaccine - generally DNA- or messenger RNA (mRNA)-based - containing sequences encoding these specific antigens.

Recent Phase 1/2 data published in Nature Medicine by colleagues at Johns Hopkins provide strong support for this strategy in HCC. In this study, 36 patients with advanced HCC were treated with the PD-1 inhibitor pembrolizumab and a personalized DNA-based neoantigen vaccine (GNOS-PV02)[64]. The combination was considered safe and achieved an ORR of nearly 33%, almost twice the rate expected with pembrolizumab monotherapy in this population. Importantly, post-treatment tumor biopsies demonstrated that the vaccine induced T cells to recognize the vaccine-encoded neoantigens and migrate into the tumor to kill cancer cells. This illustrates that personalized vaccines can enhance clinical responses to ICI therapy and represent a promising approach for de novo anti-tumor immunity.

The search for predictive biomarkers

One of the most important unmet needs in HCC is the development of robust predictive biomarkers to guide treatment, as the growing number of effective therapies increases the importance of selecting the right treatment for the right patient at the right time. In practice, a minimal biomarker panel could include Catenin beta 1 (CTNNB1) or Wingless-related integration site (Wnt)-pathway alterations, angiogenic and interferon gene-expression signatures, simple immune histopathology, and circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA)- or epigenetic-based readouts, complemented by noninvasive assessment of the gut-liver axis. Prospective validation of such panels will be critical for stratifying patients toward dual ICI, anti-VEGF-anchored regimens, or TACE-plus strategies and for enriching future clinical trials.

Wnt/β-catenin signaling as a mediator of immune exclusion

One of the most well-established mechanisms of primary resistance to immunotherapy in HCC involves the aberrant activation of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. This highly conserved pathway is essential for normal liver development and regeneration, but mutations in its components, particularly in the gene CTNNB1 which encodes β-catenin, are found in a large subset of HCCs[65].

Numerous preclinical and large-scale clinical-genomic correlative studies have demonstrated a strong and consistent association between activated β-catenin signaling and an immunologically “cold” or “non-T-cell-inflamed” TME[66]. The underlying mechanism appears to involve suppression of key chemokines, such as Chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 4 (CCL4) and Chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 10 (CXCL10), which are necessary for recruitment of effector T cells into the tumor bed. This results in an “immune-excluded” phenotype, in which T cells may be present in the periphery but are physically barred from infiltrating the tumor parenchyma, rendering ICIs ineffective[67]. Consequently, the mutational status of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway is a strong candidate biomarker for predicting poor response to ICI therapy and may help identify patients who could be spared ineffective treatment or who might benefit from alternative strategies or combination therapies designed to overcome this exclusion.

Mechanistically, β-catenin-driven tumors downregulate chemokines such as CCL4 and CXCL10, impairing recruitment of basic leucine zipper ATF-like transcription factor 3 (BATF3)-dependent dendritic cells and CD8+ T cells into the tumor bed. As a result, these tumors exhibit an immune-excluded phenotype with poor T-cell infiltration despite preserved peripheral immunity, which correlates with primary resistance to PD-1/PD-L1 blockade in multiple retrospective HCC cohorts. These observations support the use of Wnt/β-catenin alterations as a negative predictive biomarker for ICI monotherapy and motivate trials combining ICIs with Wnt-pathway modulators, oncolytic viruses, or cell-based therapies designed to bypass defective T-cell trafficking.

The gut microbiome: a modulator of therapeutic response

An emerging area of research focuses on the gut-liver axis and the gut microbiome’s role in mediating cancer initiation and treatment response[68]. The gut microbiome, the collective community of bacteria inhabiting the gastrointestinal tract, shapes and modulates the host immune response. Gut microbial dysbiosis - an imbalance in microbial populations - correlates with chronic liver disease and the development of HCC.

Accumulating evidence across various cancer types, including HCC, indicates that a patient’s gut microbiota composition can influence response to immunotherapy. This raises the exciting possibility that gut microbiota signatures could serve as noninvasive fecal biomarkers to predict responders vs. nonresponders. Furthermore, it suggests that the microbiome could be therapeutically modulated - through fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT), targeted probiotics, or dietary modification - as a novel approach to optimize immunotherapy efficacy and overcome resistance[69].

CONCLUSION AND FUTURE PERSPECTIVES

Synthesis of the current, highly integrated treatment algorithm for HCC

The field of HCC therapies has changed dramatically over the past five years - from a narrow range of treatment options with limited responses to an innovative landscape underpinned by profound insights into tumor biology. The transition from monotherapy-based TKI approaches to combinatorial therapies is irreversible. This shift has raised the standard for first-line systemic treatment in advanced disease, as multiple potent immunotherapy-based combinations have recently been established, including the anti-PD-L1/anti-VEGF regimen of Atezo + Bev, the dual long-acting ICI STRIDE regimen of durvalumab plus tremelimumab, and the nivolumab plus ipilimumab combination.

Additionally, the field has shifted from focusing solely on optimizing systemic therapy to adopting a more comprehensive perspective. Modern HCC management emphasizes the strategic combination of potent systemic agents with traditional locoregional therapies. The combination of TACE, an ICI, and an anti-angiogenic agent in the EMERALD-1 and LEAP-012 trials has established a new frontline standard for patients with intermediate-stage disease by exploiting locally induced immune modulation during tumor ablation to achieve systemic effects. Finally, the promising activity of these combinations is being explored in the neoadjuvant and conversion settings, expanding the cohort of patients eligible for curative-intent surgery and transplantation and fundamentally altering therapeutic objectives for many.

Addressing unmet needs and charting the course forward

Looking forward, the central challenge is no longer the absence of active agents but how to deploy them rationally in a cirrhotic population - through biomarker-guided selection, cirrhosis-specific safety algorithms, and evidence-based sequencing after ICI- or TACE-based regimens. Despite this impressive progress, substantial challenges remain. A major unmet need, emerging now that at least three highly efficacious first-line options for advanced disease exist, is optimizing treatment sequences. Once progressive disease occurs on these therapies, the optimal third-line therapy remains to be determined, not only in terms of comparative effectiveness but also regarding the sequencing of second- and third-line therapies. These questions are becoming major clinical and research priorities. Similarly, it remains to be determined how prior treatment with a TACE-plus regimen in intermediate-stage disease will impact the choice and effectiveness of subsequent therapy for advanced disease.

As at least three distinct, highly effective first-line options now exist, post-progression sequencing has become a major unmet need. After failure of ICI-based combinations, TKIs such as lenvatinib and cabozantinib remain key options, whereas reuse of locoregional therapies must be balanced against the risk of liver decompensation. Prospective studies are required to define optimal second- and third-line sequences for specific first-line backbones.

Toxicity-management issues: Combination regimens, particularly those containing TKIs, carry a notable burden of adverse events that require proactive, patient-specific management to preserve quality of life and allow continuation of therapy. Most importantly, the field urgently needs predictive biomarkers that can be developed and clinically validated. The shift from an empiric, “one-size-fits-all” approach to a personalized paradigm - where therapies are selected based on specific biological drivers of an individual’s tumor, such as Wnt/β-catenin pathway status, the immune signature of the TME, or gut microbiome composition - represents the next major frontier in HCC research.

Concluding remarks

Treatments for HCC in recent years, enabled by rationally designed combination therapies that bridge systemic and locoregional approaches, have been transformational. For the first time, many patients with advanced or intermediate-stage disease now have access to therapies that provide durable responses and survival benefits. The HCC treatment of the future will continue to rely on the thoughtful integration of increasingly powerful systemic, locoregional, and cellular therapies, alongside the development and implementation of predictive biomarkers to guide appropriate, truly personalized therapy and maximize overall patient prognosis.

CONCLUSION

We therefore conclude that HCC develops within a truly tolerogenic, heterogeneous TME that shapes its therapeutic vulnerabilities. The last five years have seen the emergence of mechanism-based combination strategies, transforming the standard of care: anti-PD-L1 plus anti-VEGF therapy has established dual ICB as the first-line standard in advanced disease, and TACE-plus combinations have demonstrated that locoregional priming can drive systemic immune activation in a subset of intermediate-stage patients. Clinical and translational data support a pragmatic, TME-based paradigm - characterizing inflamed, immune-excluded, and immune-desert states - to guide rational treatment selection, integrate RT/ablation/HAIC/TARE when indicated, and expand curative windows via neoadjuvant and conversion approaches.

Implementation must be accompanied by cirrhosis-specific safety algorithms (immune-related hepatitis, portal-hypertension bleeding risk, antiviral stewardship), disciplined use of TACE to avoid liver decompensation, and clearly defined post-progression sequencing after ICI- or TACE-based regimens. To move beyond empirical selection, we prioritize a minimal, deployable biomarker set - β-catenin-mediated immune exclusion, angiogenic and interferon signatures, simple immune histopathology, ctDNA/epigenetic readouts, and gut-liver axis features - while encouraging radiomics and spatial profiling where available.

Looking forward, next-generation modalities - including TIGIT and other checkpoint inhibitors, costimulatory agonists, oncolytic and STING-pathway activators, personalized neoantigen vaccines, and GPC3-directed cellular therapies - should be developed and tested in phenotype-enriched trials with endpoints aligned to intent (major pathologic response for neoadjuvant settings; durable survival and organ-sparing metrics for conversion). Regional etiologic heterogeneity and real-world practice patterns should be prospectively incorporated to enhance generalizability.

DECLARATIONS

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the use of the drawing software Figdraw (IOAISbca9f, AIPAA64034) in preparing the figures.

Authors’ contributions

Made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the study and performed data analysis and interpretation: Li M, Liu W, Wu Y

Performed data acquisition and provided administrative, technical, and material support: Chi J, Song W, Lin H

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Financial support and sponsorship

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82403804, 82300724).

Conflicts of interest

All authors declared that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026.

REFERENCES

1. Tan EY, Danpanichkul P, Yong JN, et al. Liver cancer in 2021: Global Burden of Disease study. J Hepatol. 2025;82:851-60.

2. Li Q, Ding C, Cao M, et al. Global epidemiology of liver cancer 2022: an emphasis on geographic disparities. Chin Med J. 2024;137:2334-42.

3. Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H, et al. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2024;74:229-63.

4. Du D, Liu C, Qin M, et al. Metabolic dysregulation and emerging therapeutical targets for hepatocellular carcinoma. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2022;12:558-80.

5. Deng Q, Huang Y, Zeng J, et al. Recent advancements in the small-molecule drugs for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC): structure-activity relationships, pharmacological activities, and the clinical trials. Biomed Pharmacother. 2024;179:117343.

6. Sangro B, Chan SL, Meyer T, Reig M, El-Khoueiry A, Galle PR. Diagnosis and management of toxicities of immune checkpoint inhibitors in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2020;72:320-41.

7. Ruiz de Galarreta M, Bresnahan E, Molina-Sánchez P, et al. β-catenin activation promotes immune escape and resistance to anti-PD-1 therapy in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Discov. 2019;9:1124-41.

8. Zhou J, Wang W, Li Q. Potential therapeutic targets in the tumor microenvironment of hepatocellular carcinoma: reversing the protumor effect of tumor-associated macrophages. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2021;40:73.

9. Ho DW, Tsui YM, Chan LK, et al. Single-cell RNA sequencing shows the immunosuppressive landscape and tumor heterogeneity of HBV-associated hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Commun. 2021;12:3684.

10. Song W, Li M, Liu W, et al. Role of immune cell homeostasis in research and treatment response in hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Exp Med. 2025;25:42.

11. Yoshiji H, Kuriyama S, Yoshii J, et al. Involvement of the vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-1 in murine hepatocellular carcinoma development. J Hepatol. 2004;41:97-103.

12. Sieghart W, Hucke F, Peck-Radosavljevic M. Transarterial chemoembolization: modalities, indication, and patient selection. J Hepatol. 2015;62:1187-95.

13. McDermott DF, Huseni MA, Atkins MB, et al. Clinical activity and molecular correlates of response to atezolizumab alone or in combination with bevacizumab versus sunitinib in renal cell carcinoma. Nat Med. 2018;24:749-57.

14. Li D, Toh HC, Merle P, et al. Atezolizumab plus bevacizumab versus sorafenib for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: results from older adults enrolled in the IMbrave150 randomized clinical trial. Liver Cancer. 2022;11:558-71.

15. Finn RS, Qin S, Ikeda M, et al; IMbrave150 Investigators. Atezolizumab plus bevacizumab in unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1894-905.

16. Kudo M. A paradigm change in the treatment strategy for hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Cancer. 2020;9:367-77.

17. Zhu H, Chen XP, Zhang WG, Luo SF, Zhang BX. Expression and significance of new inhibitor of apoptosis protein survivin in hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:3855-9.

18. Yang Y, Zhang Y, Iwamoto H, et al. Discontinuation of anti-VEGF cancer therapy promotes metastasis through a liver revascularization mechanism. Nat Commun. 2016;7:12680.

19. Liu WJ, Wang L, Zhou FM, et al. Elevated NOX4 promotes tumorigenesis and acquired EGFR-TKIs resistance via enhancing IL-8/PD-L1 signaling in NSCLC. Drug Resist Updat. 2023;70:100987.

20. Liu G, Zhou W, Li X, et al. Case report: complete response of primary massive hepatocellular carcinoma to anti-programmed death ligand-1 antibody following progression on anti-programmed death-1 antibody. Front Immunol. 2021;12:712351.

21. Sangro B, Chan SL, Kelley RK, et al; HIMALAYA investigators. Four-year overall survival update from the phase III HIMALAYA study of tremelimumab plus durvalumab in unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. Ann Oncol. 2024;35:448-57.

22. Sangro B, Galle PR, Kelley RK, et al. Patient-reported outcomes from the phase III HIMALAYA study of tremelimumab plus durvalumab in unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2024;42:2790-9.

23. Abou-Alfa GK, Lau G, Kudo M, et al. Plain language summary of the HIMALAYA study: tremelimumab and durvalumab for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma (liver cancer). Future Oncol. 2023;19:2505-16.

24. Akbay EA, Koyama S, Carretero J, et al. Activation of the PD-1 pathway contributes to immune escape in EGFR-driven lung tumors. Cancer Discov. 2013;3:1355-63.

25. Jing Y, Liu J, Ye Y, et al. Multi-omics prediction of immune-related adverse events during checkpoint immunotherapy. Nat Commun. 2020;11:4946.

26. Kim DJ, Anandh S, Null JL, et al. Priming a vascular-selective cytokine response permits CD8+ T-cell entry into tumors. Nat Commun. 2023;14:2122.

27. Sun X, Zhang Q, Mei J, Yang Z, Chen M, Liang T. Real-world efficiency of lenvatinib plus PD-1 blockades in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: an exploration for expanded indications. BMC Cancer. 2022;22:293.

28. Llovet JM, Kudo M, Merle P, et al; LEAP-002 Investigators. Lenvatinib plus pembrolizumab versus lenvatinib plus placebo for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (LEAP-002): a randomised, double-blind, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2023;24:1399-410.

29. Finn RS, Kudo M, Merle P, et al. Health-related quality of life analysis of the LEAP-002 study of lenvatinib plus pembrolizumab versus lenvatinib as first-line treatment for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. ESMO Open. 2025;10:105065.

30. Yu X, Wei C, Cui R, Jiang O. Lenvatinib plus immune checkpoint inhibitors versus lenvatinib monotherapy as treatment for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: a meta-analysis. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2023;16:321-31.

31. Galle PR, Decaens T, Kudo M, et al. Nivolumab (NIVO) plus ipilimumab (IPI) vs lenvatinib (LEN) or sorafenib (SOR) as first-line treatment for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma (uHCC): first results from CheckMate 9DW. JCO. 2024;42:LBA4008.

32. Cheng AL, Qin S, Ikeda M, et al. Updated efficacy and safety data from IMbrave150: Atezolizumab plus bevacizumab vs. sorafenib for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2022;76:862-73.

33. Abou-Alfa GK, Lau G, Kudo M, et al. Tremelimumab plus durvalumab in unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. NEJM Evid. 2022;1:EVIDoa2100070.

34. Yau T, Galle PR, Decaens T, et al; CheckMate 9DW investigators. Nivolumab plus ipilimumab versus lenvatinib or sorafenib as first-line treatment for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma (CheckMate 9DW): an open-label, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2025;405:1851-64.

35. Ricke J, Klümpen HJ, Amthauer H, et al. Impact of combined selective internal radiation therapy and sorafenib on survival in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2019;71:1164-74.

36. Duffy AG, Ulahannan SV, Makorova-Rusher O, et al. Tremelimumab in combination with ablation in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2017;66:545-51.

37. Sangro B, Kudo M, Erinjeri JP, et al; EMERALD-1 Investigators. Durvalumab with or without bevacizumab with transarterial chemoembolisation in hepatocellular carcinoma (EMERALD-1): a multiregional, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 study. Lancet. 2025;405:216-32.

38. Llovet JM, Vogel A, Madoff DC, et al. Randomized phase 3 LEAP-012 study: transarterial chemoembolization with or without lenvatinib plus pembrolizumab for intermediate-stage hepatocellular carcinoma not amenable to curative treatment. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2022;45:405-12.

39. Kudo M, Ren Z, Guo Y, et al; LEAP-012 investigators. Transarterial chemoembolisation combined with lenvatinib plus pembrolizumab versus dual placebo for unresectable, non-metastatic hepatocellular carcinoma (LEAP-012): a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, phase 3 study. Lancet. 2025;405:203-15.

40. Singal AG, Rich NE, Mehta N, et al. Direct-acting antiviral therapy for hepatitis C virus infection is associated with increased survival in patients with a history of hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2019;157:1253-63.e2.

41. Ma J, Xin Y, Wang Q, Ding L. Roles of cGAS-STING pathway in radiotherapy combined with immunotherapy for hepatocellular carcinoma. Mol Cancer Ther. 2024;23:447-53.

42. Zhao S, Zhang Y, Lu X, et al. CDC20 regulates the cell proliferation and radiosensitivity of P53 mutant HCC cells through the Bcl-2/Bax pathway. Int J Biol Sci. 2021;17:3608-21.

43. Zhao S, Wei C, Tang H, et al. Elevated DNA polymerase delta 1 expression correlates with tumor progression and immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment in hepatocellular carcinoma. Front Oncol. 2021;11:736363.

44. Rao Q, Zuo B, Lu Z, et al. Tumor-derived exosomes elicit tumor suppression in murine hepatocellular carcinoma models and humans in vitro. Hepatology. 2016;64:456-72.

45. Tang X, Ding M, Lu B, et al. Outcomes of ultrasound-guided percutaneous microwave ablation versus surgical resection for symptomatic large hepatic hemangiomas. Int J Hyperthermia. 2019;36:632-9.

46. Nam JY, Lee YB, Lee JH, et al. A prognostic prediction model of transarterial radioembolization in hepatocellular carcinoma: SNAP-HCC. Dig Dis Sci. 2022;67:329-36.

47. Xu T, Wang W, Bao R, et al. Anti-PD-1 plus anti-angiogenesis combined with chemotherapy in patients with HER2-negative advanced or metastatic gastric cancer: a multi-institutional retrospective study. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2023;14:175-86.

48. El-Khoueiry AB, Hanna DL, Llovet J, Kelley RK. Cabozantinib: an evolving therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Treat Rev. 2021;98:102221.

49. Kimura T, Kato Y, Ozawa Y, et al. Immunomodulatory activity of lenvatinib contributes to antitumor activity in the Hepa1-6 hepatocellular carcinoma model. Cancer Sci. 2018;109:3993-4002.

50. Cucchetti A, Serenari M, Sposito C, et al. Including mRECIST in the Metroticket 2.0 criteria improves prediction of hepatocellular carcinoma-related death after liver transplant. J Hepatol. 2020;73:342-8.

51. Singal AG, Yarchoan M, Yopp A, Sapisochin G, Pinato DJ, Pillai A. Neoadjuvant and adjuvant systemic therapy in HCC: current status and the future. Hepatol Commun. 2024;8:e0430.

52. Ho WJ, Zhu Q, Durham J, et al. Neoadjuvant cabozantinib and nivolumab converts locally advanced hcc into resectable disease with enhanced antitumor immunity. Nat Cancer. 2021;2:891-903.

53. Goodsell KE, Tao AJ, Park JO. Neoadjuvant therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma-priming precision innovations to transform HCC treatment. Front Surg. 2025;12:1531852.

54. Dikilitas M. Why adjuvant and neoadjuvant therapy failed in HCC. Can the new immunotherapy be expected to be better? J Gastrointest Cancer. 2020;51:1193-6.

55. Batra SA, Rathi P, Guo L, et al. Glypican-3-specific CAR T cells coexpressing IL15 and IL21 have superior expansion and antitumor activity against hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Immunol Res. 2020;8:309-20.

56. Makkouk A, Yang XC, Barca T, et al. Off-the-shelf Vδ1 gamma delta T cells engineered with glypican-3 (GPC-3)-specific chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) and soluble IL-15 display robust antitumor efficacy against hepatocellular carcinoma. J Immunother Cancer. 2021;9:e003441.

57. Zhang Q, Fu Q, Cao W, et al. Phase I study of C-CAR031, a GPC3-specific TGFβRIIDN armored autologous CAR-T, in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). JCO. 2024;42:4019.

58. Fu Q, Zheng Y, Fang W, et al. RUNX-3-expressing CAR T cells targeting glypican-3 in patients with heavily pretreated advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: a phase I trial. EClinicalMedicine. 2023;63:102175.

59. Huhn GD, Wilkin A, Mussini C, et al; AMBER and EMERALD study groups. Phase I study of Ori-C101, an armored GPC3-directed CAR-T, in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). J Clin Oncol. 2025;43:4084.

60. Liu WN, Harden SL, Tan SLW, et al. Single-cell RNA sequencing reveals anti-tumor potency of CD56+ NK cells and CD8+ T cells in humanized mice via PD-1 and TIGIT co-targeting. Mol Ther. 2024;32:3895-914.

61. Finn RS, Ryoo BY, Hsu CH, et al. Tiragolumab in combination with atezolizumab and bevacizumab in patients with unresectable, locally advanced or metastatic hepatocellular carcinoma (MORPHEUS-Liver): a randomised, open-label, phase 1b-2, study. Lancet Oncol. 2025;26:214-26.

62. Badhrinarayanan S, Cotter C, Zhu H, Lin YC, Kudo M, Li D. IMbrave152/SKYSCRAPER-14: a phase III study of atezolizumab, bevacizumab and tiragolumab in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Future Oncol. 2024;20:2049-57.

63. Wang J, Cao Y, Tian Y, Dai C, Jin T, Xu F. A novel prognostic nomogram based on TIGIT and NKG2A can predict relapse-free survival of hepatocellular carcinoma after hepatectomy. Cancer Med. 2024;13:e70419.

64. Yarchoan M, Gane EJ, Marron TU, et al. Personalized neoantigen vaccine and pembrolizumab in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: a phase 1/2 trial. Nat Med. 2024;30:1044-53.

65. Gao Q, Zhu H, Dong L, et al. Integrated proteogenomic characterization of HBV-related hepatocellular carcinoma. Cell. 2019;179:561-77.e22.

66. Dadey RE, Li R, Griner J, et al. Multiomics identifies tumor-intrinsic SREBP1 driving immune exclusion in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Immunother Cancer. 2025;13:e011537.

67. Perugorria MJ, Olaizola P, Labiano I, et al. Wnt-β-catenin signalling in liver development, health and disease. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;16:121-36.

68. Milosevic I, Vujovic A, Barac A, et al. Gut-liver axis, gut microbiota, and its modulation in the management of liver diseases: a review of the literature. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20:395.

Cite This Article

How to Cite

Download Citation

Export Citation File:

Type of Import

Tips on Downloading Citation

Citation Manager File Format

Type of Import

Direct Import: When the Direct Import option is selected (the default state), a dialogue box will give you the option to Save or Open the downloaded citation data. Choosing Open will either launch your citation manager or give you a choice of applications with which to use the metadata. The Save option saves the file locally for later use.

Indirect Import: When the Indirect Import option is selected, the metadata is displayed and may be copied and pasted as needed.

About This Article

Special Topic

Copyright

Data & Comments

Data

Comments

Comments must be written in English. Spam, offensive content, impersonation, and private information will not be permitted. If any comment is reported and identified as inappropriate content by OAE staff, the comment will be removed without notice. If you have any queries or need any help, please contact us at support@oaepublish.com.