Monoclonal gammopathies and their management in Gaucher disease type 1

Abstract

Gaucher disease type 1 (GD1) is a rare autosomal recessive genetic disorder characterized by deficiency of the lysosomal enzyme glucocerebrosidase. Among the various clinical manifestations that have been well described for decades, a more recent finding has been the association of GD1 with increased risk of various malignancies, including multiple myeloma. We present a brief review describing the relationship between GD1 and monoclonal gammopathies, as well as the modern standard in the monitoring and management of these conditions. This review aims to increase awareness of a disease that, while rare, is associated with a common malignancy with robust, novel treatment options.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

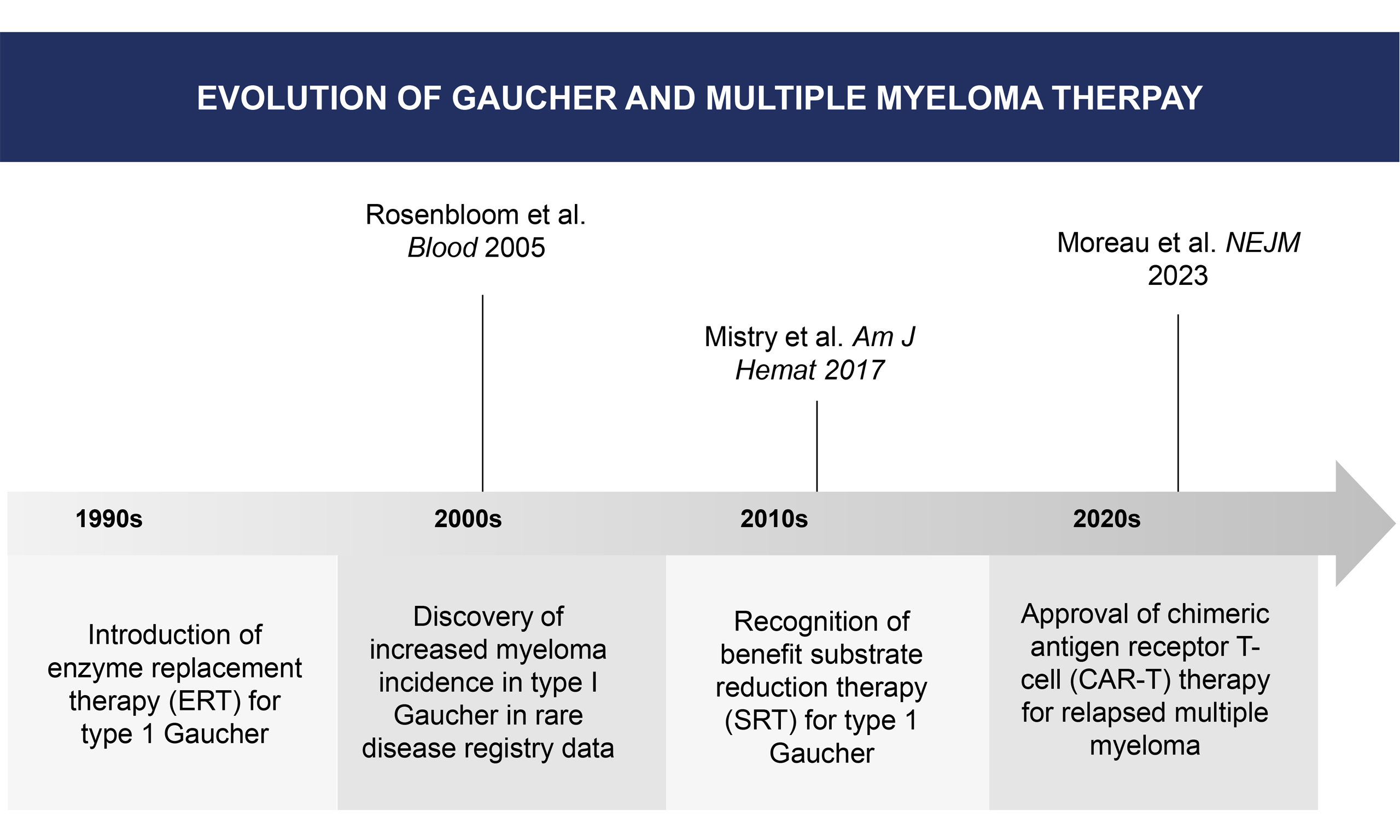

Gaucher disease (GD), which develops due to an inherited deficiency of glucocerebrosidase, is the most common lysosomal storage disease globally[1]. The hallmark pathological finding in Gaucher is the excessive buildup of glucosylceramide (GC) and its bioactive metabolite, glucosylsphingosine, in macrophages. This leads to chronic inflammation in untreated patients, who develop hepatosplenomegaly, anemia, thrombocytopenia, potentially crippling bone involvement, and possible neurological consequences[2]. Of the three known types of Gaucher disease (types 1, 2, and 3), type 1 (GD1) has received the most attention from researchers regarding malignancy. It has been repeatedly reported that the incidence of malignancies, especially hematological malignancies, is increased in GD1[3-5]. The purpose of this review is to present information on the incidence of these neoplasms and their treatment. This review was based on literature identified through PubMed and the International Gaucher Registry reports up to August 2025.

INCIDENCE OF MGUS AND MALIGNANCIES IN GAUCHER DISEASE TYPE 1

The tissue microenvironment in GD1 contains a number of factors that contribute to carcinogenesis. These include the accumulation of the growth-promoting metabolite GC, cancer-promoting metabolic shunting (Warburg effect), M2 polarization of GC-saturated macrophages, chronic B-cell stimulation, masked metabolic syndrome with insulin resistance, iron overload, lysosomal dysregulation, and endoplasmic reticulum stress[6,7]. Various studies have reported an overall increased risk of hematological malignancies in GD1 patients, with the risk of multiple myeloma (MM) specifically ranging from 5.9- to 51.1-fold higher[8].

In a recent study from the Gaucher Registry, the risk of MM was ninefold higher than in the wild-type population, and the age of presentation was younger than reported in prior studies[5]. In addition, higher

It is notable that patients with MGUS due to lipid-reactive M-spikes showed a reduction of monoclonal protein with substrate reduction therapy (SRT)[10]. Studies have demonstrated an increased risk of B-cell malignancies in murine GD models, which is ameliorated by SRT using a glucosylsphingosine inhibitor, supporting the role of glycosphingolipids in driving carcinogenesis in GD1 models[11,12]. In a study of 63 GD1 patients, none of the 50 receiving ERT developed MGUS, and immunoglobulin levels decreased overall[13]. Similarly, in the murine GD model, SRT reduced disease-associated gammopathy[12]. Eliglustat, an SRT approved for use in humans, has demonstrated efficacy in reducing lyso-GL1 plasma concentrations, a potential stimulatory antigen for the development of monoclonal antibodies[14].

There is evidence that GD patients who develop MGUS do so as a consequence of chronic secretion of proinflammatory cytokines-namely interleukin (IL)-6 and IL-10-by macrophages alternatively activated due to prolonged accumulation of glycosphingolipids. This results in clonal expansion of B-lymphocytes and plasma cells[4]. In addition, some data implicate GC in B-cell stimulation, leading to the formation of

In patients with GD1 who develop solid tumors, there is an increased risk of hepatocellular carcinoma, renal cell carcinoma, breast cancer, and malignant melanoma. Unlike other metabolic disorders that primarily affect a specific organ, these sites of neoplasia do not correspond to organs typically affected by GD1. The increased risk of melanoma may be related to defective T-cell function and impaired immune surveillance in GD1 patients, possibly associated with lyso-GL1[5].

THE MANAGEMENT OF MONOCLONAL GAMMOPATHIES

MGUS

MGUS is a non-malignant plasma cell disorder with the potential to evolve into smoldering MM (SMM) or MM. The incidence of MGUS increases with age, and its prevalence in adults aged 70 and older was 5.3% in a large population study[18]. As reviewed above, the incidence is higher in patients with GD1.

The diagnostic criteria require the detection of a serum monoclonal protein under 3 g/dL or a clonal increase in the serum light chain ratio, fewer than 10% clonal plasma cells on bone marrow examination, and no classic MM clinical features (hypercalcemia, renal impairment, anemia, or lytic bone lesions)[19].

The vast majority of patients diagnosed with MGUS do not progress to MM. The risk of progression is generally described as roughly 1% per year, though specific risk factors can influence an individual patient’s risk. Higher-risk features include an abnormal free light chain ratio, a monoclonal protein (M-protein)

As MGUS, by definition, does not cause clinical manifestations, its management is focused on periodic monitoring for progression to SMM or MM, rather than treatment. The frequency of monitoring is based on baseline risk assessment. Guideline recommendations for frequency of monitoring range from annually for high-risk MGUS (M-protein ≥ 1.5g/dL, abnormal light chain ratio, or non-IgG type), to every 2-3 years for low-risk MGUS (M-protein < 1.5g/dL, normal light chain ratio, and IgG type)[20]. Potential future improvements in the MGUS management include refinement of tools to risk-stratify patients, which would allow intensified monitoring for some and reduced monitoring for others.

SMOLDERING MULTIPLE MYELOMA

SMM, similar to MGUS, is an asymptomatic premalignant state. It differs from MGUS in that it requires either ≥ 3g/dL of serum monoclonal protein or 10%-59% clonal plasma cells in bone marrow. Several risk stratification models exist to help prognosticate risk of progression to MM, guide monitoring frequency, and inform selection of therapy.

The International Myeloma Working Group (IMWG) uses three readily available risk factors to predict progression to MM: M-protein > 2 g/dL, involved-to-uninvolved free light chain ratio > 20, and bone marrow clonal plasma cells > 20%. A retrospective study of 1,996 patients validated the use of these risk factors. The two-year risk of progression to MM was 6% for patients with no risk factors, 18% for those with one factor, and 44% for those with two to three factors. Further stratification could be achieved by incorporating high-risk cytogenetic abnormalities [t(4;14), t(14;16), +1q, or del13q] as a fourth risk factor[21].

The standard of care for low and intermediate-risk SMM is observation until progression to MM. Lenalidomide, an immunomodulatory drug with regulatory approval in MM, did not demonstrate statistically significant progression-free survival (PFS) benefit compared to observation in the Mayo 2018 intermediate risk subgroup. Lenalidomide did show a significant PFS benefit in the high-risk subgroup, with a 3-year PFS of 91% compared to 66% for the observation arm, though without an improvement in median overall survival[22].

The phase III AQUILA trial studied high-risk SMM. The protocol randomized patients to three years of the anti-CD38 monoclonal antibody daratumumab or active monitoring. With a median follow-up of 65.2 months, PFS was significantly higher with daratumumab than with active monitoring [hazard ratio (HR) 0.49; 95%confidence interval (CI), 0.36 to 0.67; P < 0.001]. Five-year overall survival was 93.0% for the daratumumab arm compared to 86.9% in the control arm, although no P-value was reported for Overall Survival (OS). Furthermore, post-protocol first-line therapy in the control arm included anti-CD38 therapy in only 35%, raising the question of whether overall survival would have been similar if a higher proportion of patients in the control arm received an anti-CD38 regimen at the time of future progression[23].

MULTIPLE MYELOMA

MM is a monoclonal gammopathy that typically causes clinical manifestations, classically including osteolytic lesions, renal dysfunction, anemia, and hypercalcemia. The revised IMWG definition requires

Once a diagnosis of MM is confirmed, patients are risk-stratified, most commonly using cytogenetics,

The therapeutic landscape of frontline and relapsed and refractory MM has rapidly expanded and evolved over the prior decade, and a detailed discussion of each treatment regimen is beyond the scope of this article. Per mSMART guidelines, a four-drug regimen is recommended for all transplant eligible patients, including an anti-CD38 monoclonal antibody, lenalidomide, bortezomib, and dexamethasone. For transplant ineligible patients, similar four-drug regimens are recommended, except for frail patients, for whom three- or two-drug regimen is advised.

Despite very high overall response rates and durability of response of conventional triplet and quadruplet regimens, these therapies are not considered curative. Goals of therapy are to reverse end-organ damage and to improve symptoms, quality of life, and overall survival. In the United States, the combination of bortezomib, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone served as a standard of care for several years prior to the advent of four-drug regimens. When compared against the doublet regimen of lenalidomide and dexamethasone in a phase III clinical trial, the triplet improved overall survival (median not reached versus 69 months, HR 0.71, 95%CI 0.54-0.93), albeit with higher toxicity including peripheral neuropathy[25]. Most four-drug regimens incorporating the addition of an anti-CD38 monoclonal antibody improve overall response rate, depth of response, and PFS, but have not yet consistently demonstrated improved overall survival.

In the first relapse setting, therapies from the same therapeutic classes as first-line treatment are used, depending on whether a patient is considered refractory to lenalidomide or anti-CD38 monoclonal antibody therapies. Patients who are refractory to lenalidomide or bortezomib may have disease that responds to pomalidomide or carfilzomib, respectively[26].

There are multiple novel Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved regimens in the second- and later-relapse setting. For patients who are refractory to lenalidomide, pomalidomide, bortezomib, carfilzomib, and an anti-CD38 monoclonal antibody, the development and approval of B-cell maturation antigen (BCMA) directed therapies have offered improved response rates and median durations of response compared to previous later line regimens. BCMA is selectively and widely expressed on plasma cells.

Idecabtagene vicleucel (Ide-cel) and ciltacabtagene autoleucel (cilta-cel) are chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-T cell products with regulatory approval in this setting, with data in randomized phase 3 trials demonstrating improved PFS compared to standard approved therapies. Ide-cel demonstrated a median PFS of 13.8 months versus 4.4 months for standard therapy (HR 0.49, 95%CI 0.38-0.65, P < 0.001)[27].

BCMA-directed CAR-T cell therapies are distinguished from other MM therapies by virtue of being administered as a single treatment, rather than on an ongoing, indefinite basis. Further, the toxicity profile is notable for neurologic toxicity and cytokine release syndrome (CRS). CRS is characterized by an inflammatory response, featuring fever, hypotension, and potential for life threatening multiorgan failure. While CRS occurs in most patients, 88% in the KarMMa-3 trial utilizing ide-cel, grade 3 and higher CRS occurred in just 5%[27].

Elranatamab and teclistamab are bispecific monoclonal antibodies specific to both BCMA and CD3 T-cells. Both have regulatory approval in the United States for patients who have received four or more lines of prior therapy including a proteasome inhibitor, immunomodulatory agent, and an anti-CD38 monoclonal antibody. Overall response rates for teclistamab and Elranatamab were 63% and 61%, respectively, in

Minimal residual disease (MRD) assessment has emerged as an endpoint in clinical trials and may potentially serve as a future tool in routine clinical practice to help tailor treatment of patients with MM. The revised IMWG response criteria include MRD negativity as a measure of response, in addition to standard response criteria; however, National Comprehensive Cancer Network Guidelines do not yet specifically endorse its use in guiding management[31].

MANAGEMENT IN RELATION TO GD1

While case reports and animal data suggest the possibility of altering the course of a monoclonal gammopathy with GD1 directed therapy, it is not yet known whether any specific GD1 therapy reduces the risk of developing a monoclonal gammopathy[32]. Furthermore, once SMM or MM develops, selection of SMM or MM therapy is generally not altered in a patient with GD1 compared to an unaffected patient. Currently, the only GD1-specific recommendation is screening for monoclonal gammopathy[33]. By contrast, in the general population, screening for gammopathy is not recommended.

CONCLUSION

The spectrum of monoclonal gammopathies, ranging from MGUS to MM, presents several challenges: optimizing risk stratification, deciding when to intervene and with which regimen in SMM, and sequencing the multitude of novel therapies to maintain quality of life and long-term survival in MM. The proliferation of novel targeted therapies in MM has expanded the boundaries of success in patients refractory to existing therapies, but these therapies carry unique logistical and toxicity challenges. With improvements in GD1 therapy to prevent classic Gaucher manifestations such as splenomegaly and bone disease, more focus will turn to other disorders that patients are at risk for in middle and older age.

DECLARATIONS

Authors’ contributions

Abstract, management of monoclonal gammopathies, MGUS, SMM, MM, Management in relation to GD1, conclusion: Lorber J

Gaucher disease and malignancy, incidence of MGUS and malignancies: Rosenbloom BE

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Financial support and sponsorship

None.

Conflicts of interest

All authors declared that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2025.

REFERENCES

1. Grabowski GA, Kolodny EH, Weinreb NJ, et al. Phenotypic and Genetic Variation. In: Valle DL, Antonarakis S, Ballabio A, Beaudet AL, Mitchell GA, Editors. The online metabolic and molecular bases of inherited disease. McGraw-Hill; 2019.Available from: https://ommbid.mhmedical.com/content.aspx?bookid=2709§ionid=225546386&utm_source=chatgpt.com [Last accessed on 17 Sep 2025].

2. Rosenbloom BE, Weinreb NJ. Gaucher disease: a comprehensive review. Crit Rev Oncog. 2013;18:163-75.

3. Rosenbloom BE, Weinreb NJ, Zimran A, Kacena KA, Charrow J, Ward E. Gaucher disease and cancer incidence: a study from the Gaucher Registry. Blood. 2005;105:4569-72.

4. Bonesteele G, Gargus JJ, Curtin E, Tang M, Rosenbloom B, Kimonis V. Diffuse large B-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma in Gaucher disease. Mol Genet Metab Rep. 2020;25:100663.

5. Rosenbloom BE, Cappellini MD, Weinreb NJ, et al. Cancer risk and gammopathies in 2123 adults with Gaucher disease type 1 in the International Gaucher Group Gaucher Registry. Am J Hematol. 2022;97:1337-47.

6. Erez A, Shchelochkov OA, Plon SE, et al. Insights into the pathogenesis and treatment of cancer from inborn errors of metabolism. Am J Hum Genet. 2011;88:402-21.

7. Langeveld M, Ghauharali KJ, Sauerwein HP, et al. Type I Gaucher disease, a glycosphingolipid storage disorder, is associated with insulin resistance. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:845-51.

8. Taddei TH, Kacena KA, Yang M, et al. The underrecognized progressive nature of N370S Gaucher disease and assessment of cancer risk in 403 patients. Am J Hematol. 2009;84:208-14.

9. Kyle RA, Larson DR, Therneau TM, et al. Long-term follow-up of monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:241-9.

10. Brautbar A, Elstein D, Pines G, Abrahamov A, Zimran A. Effect of enzyme replacement therapy on gammopathies in Gaucher disease. Blood Cells Mol Dis. 2004;32:214-7.

11. Nair S, Bar N, Xu ML, Dhodapkar M, Mistry PK. Glucosylsphingosine but not Saposin C, is the target antigen in Gaucher disease-associated gammopathy. Mol Genet Metab. 2020;129:286-91.

12. Mistry PK, Lukina E, Ben Turkia H, et al. Outcomes after 18 months of eliglustat therapy in treatment-naïve adults with Gaucher disease type 1: the phase 3 ENGAGE trial. Am J Hematol. 2017;92:1170-6.

13. de Fost M, Out TA, de Wilde FA, et al. Immunoglobulin and free light chain abnormalities in Gaucher disease type I: data from an adult cohort of 63 patients and review of the literature. Ann Hematol. 2008;87:439-49.

14. Mistry PK, Balwani M, Charrow J, et al. Long-term effectiveness of eliglustat treatment: a real-world analysis from the International Collaborative Gaucher Group Gaucher Registry. Am J Hematol. 2024;99:1500-10.

15. Nair S, Branagan AR, Liu J, Boddupalli CS, Mistry PK, Dhodapkar MV. Clonal immunoglobulin against lysolipids in the origin of myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:555-61.

16. Nair S, Sng J, Boddupalli CS, et al. Antigen-mediated regulation in monoclonal gammopathies and myeloma. JCI Insight. 2018;3:98259.

17. Cox TM, Rosenbloom BE, Barker RA. Gaucher disease and comorbidities: B-cell malignancy and parkinsonism. Am J Hematol. 2015;90 Suppl 1:S25-8.

18. Dispenzieri A, Katzmann JA, Kyle RA, et al. Prevalence and risk of progression of light-chain monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance: a retrospective population-based cohort study. Lancet. 2010;375:1721-8.

19. Rajkumar SV, Dimopoulos MA, Palumbo A, et al. International Myeloma Working Group updated criteria for the diagnosis of multiple myeloma. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:e538-48.

20. Kyle RA, Durie BG, Rajkumar SV, et al.; International Myeloma Working Group. Monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS) and smoldering (asymptomatic) multiple myeloma: IMWG consensus perspectives risk factors for progression and guidelines for monitoring and management. Leukemia. 2010;24:1121-7.

21. Mateos MV, Kumar S, Dimopoulos MA, et al. International Myeloma Working Group risk stratification model for smoldering multiple myeloma (SMM). Blood Cancer J. 2020;10:102.

22. Lonial S, Jacobus S, Fonseca R, et al. Randomized trial of lenalidomide versus observation in smoldering multiple myeloma. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38:1126-37.

23. Dimopoulos MA, Voorhees PM, Schjesvold F, et al.; AQUILA Investigators. Daratumumab or Active monitoring for high-risk smoldering multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2025;392:1777-88.

24. Joseph NS, Kaufman JL, Dhodapkar MV, et al. Long-term follow-up results of lenalidomide, bortezomib, and dexamethasone induction therapy and risk-adapted maintenance approach in newly diagnosed multiple myeloma. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38:1928-37.

25. Durie BGM, Hoering A, Sexton R, et al. Longer term follow-up of the randomized phase III trial SWOG S0777: bortezomib, lenalidomide and dexamethasone vs. lenalidomide and dexamethasone in patients (Pts) with previously untreated multiple myeloma without an intent for immediate autologous stem cell transplant (ASCT). Blood Cancer J. 2020;10:53.

26. Dingli D, Ailawadhi S, Bergsagel PL, et al. Therapy for relapsed multiple myeloma: guidelines from the mayo stratification for myeloma and risk-adapted therapy. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017;92:578-98.

27. Rodriguez-Otero P, Ailawadhi S, Arnulf B, et al. Ide-cel or standard regimens in relapsed and refractory multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2023;388:1002-14.

28. San-Miguel J, Dhakal B, Yong K, et al. Cilta-cel or standard Care in lenalidomide-refractory multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2023;389:335-47.

29. Moreau P, Garfall AL, van de Donk NWCJ, et al. Teclistamab in relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2022;387:495-505.

30. Lesokhin AM, Tomasson MH, Arnulf B, et al. Elranatamab in relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma: phase 2 MagnetisMM-3 trial results. Nat Med. 2023;29:2259-67.

31. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Multiple Myeloma (Version 2.2026). Available from: https://www.nccn.org/login?ReturnURL=https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/myeloma.pdf [Last accessed on 17 Sep 2025].

32. Park JH, Moore AF, Kuter DJ. Long-term follow-up of monoclonal gammopathies in Gaucher disease patients on enzyme replacement therapy. Blood. 2006;108:3336.

Cite This Article

How to Cite

Download Citation

Export Citation File:

Type of Import

Tips on Downloading Citation

Citation Manager File Format

Type of Import

Direct Import: When the Direct Import option is selected (the default state), a dialogue box will give you the option to Save or Open the downloaded citation data. Choosing Open will either launch your citation manager or give you a choice of applications with which to use the metadata. The Save option saves the file locally for later use.

Indirect Import: When the Indirect Import option is selected, the metadata is displayed and may be copied and pasted as needed.

About This Article

Special Topic

Copyright

Data & Comments

Data

Comments

Comments must be written in English. Spam, offensive content, impersonation, and private information will not be permitted. If any comment is reported and identified as inappropriate content by OAE staff, the comment will be removed without notice. If you have any queries or need any help, please contact us at support@oaepublish.com.