Prenatal exposure to multidimensional environmental factors and the risk of childhood obesity: a review

Abstract

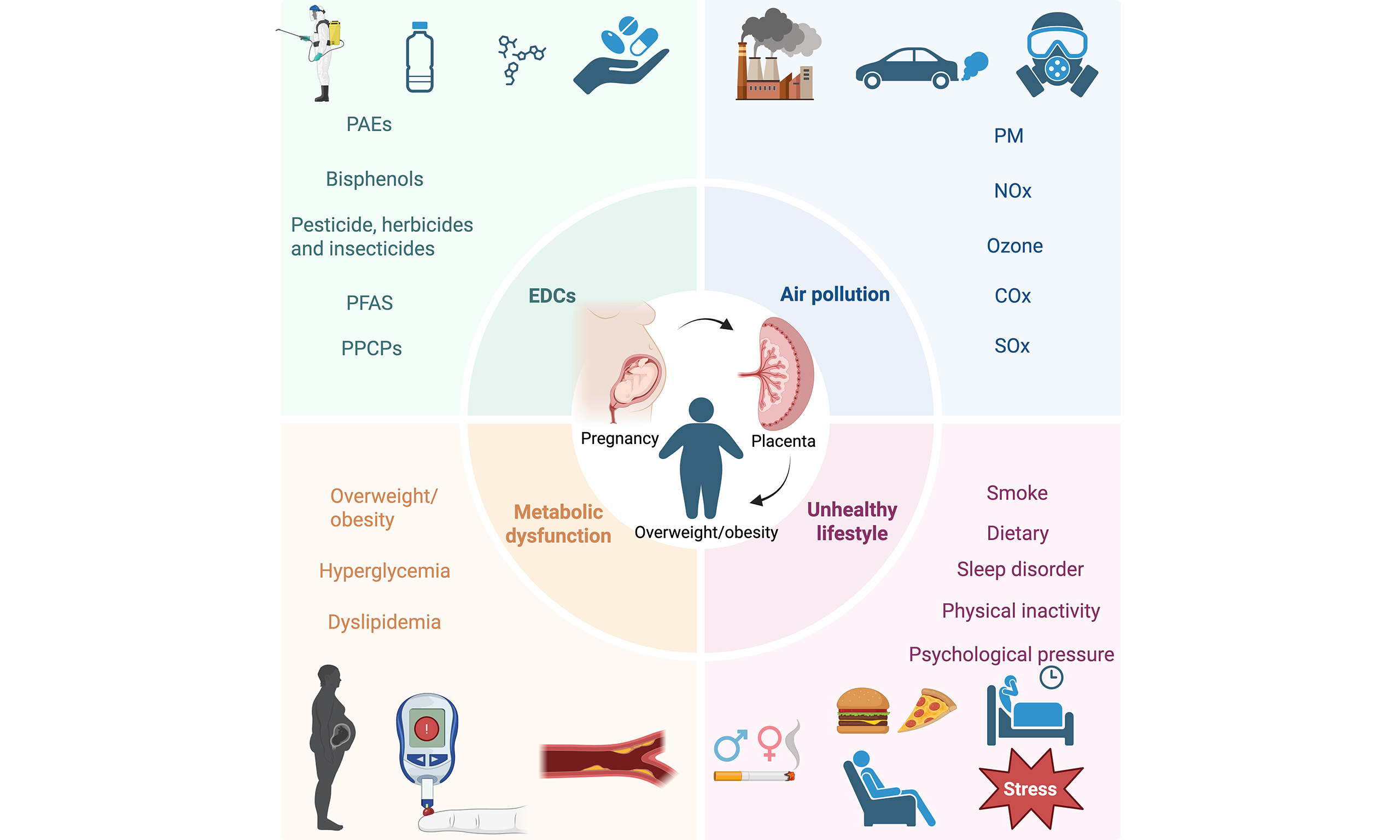

Prenatal environmental exposure is a significant factor in childhood obesity, and the underlying mechanisms of its multidimensional environmental factors are receiving increasing attention. While existing research has primarily focused on the obesity-promoting effects of individual environmental factors, comprehensive evidence on the combined impact of complex exposure systems, including endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs), air pollutants, maternal metabolic abnormalities, and adverse lifestyle choices, remains to be consolidated. This review systematically examines the combined effects of intrauterine EDCs, air pollutants, maternal metabolic abnormalities, and adverse lifestyle factors on the risk of childhood obesity. It summarizes the mechanisms through which these factors interfere with fetal energy balance programming via shared pathways, including epigenetic alterations, placental dysfunction, and metabolic inflammation. The aim is to construct a multidimensional spectrum of environmental exposures during early life, providing a theoretical basis for the early stratification of risk and the precise prevention and control of childhood obesity.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

Childhood obesity has become a serious public health challenge in both developed and developing countries, with its prevalence continuing to rise. Projections indicate that by 2035, the global obesity rate among individuals aged 5 to 19 is expected to reach 18% to 20%[1,2], highlighting the urgency of addressing this issue. Importantly, childhood obesity has been demonstrated to be associated with a number of adverse outcomes in adulthood, including hypertension, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, insulin resistance, and psychosocial issues[3-8]. Moreover, this condition has been shown to significantly increase the risk of cardiovascular and metabolic diseases, as well as premature mortality[9-11]. Conventional research has chiefly concentrated on the impact of individual behavioral factors, such as diet and exercise, on obesity[12,13]. However, the development of obesity is fundamentally the result of multifactorial, multi-pathway interactions, and a singular perspective struggles to fully elucidate its causal network[14-16]. The theoretical framework of Developmental Origins of Health and Disease (DOHaD) has undergone significant elaboration, with a growing emphasis on the pivotal role of early-life environmental exposures in metabolic programming[17]. It is evident that a multitude of intrauterine environmental factors, including endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs), air pollutants, maternal metabolic abnormalities, and adverse lifestyle choices, have the capacity to exert a persistent influence on offspring energy homeostasis and to contribute to the shaping of long-term obesity susceptibility. This phenomenon occurs through mechanisms such as epigenetic regulation[18], placental function disruption, and metabolic inflammation activation[19,20]. In recent years, there has been a gradual shift in research paradigms from single-exposure assessments to integrated exposure systems[21]. The aim of this shift has been to elucidate how multidimensional environmental factors contribute to childhood obesity through metabolic reprogramming pathways. In light of the aforementioned evidence, this review systematically integrates the latest findings on multidimensional intrauterine environmental exposures - including EDCs, air pollutants, maternal metabolic abnormalities, and adverse lifestyle choices - to elucidate their combined effects and common mechanisms in offspring obesity development. This provides a theoretical foundation for the establishment of early risk stratification systems and the development of precision prevention strategies.

PRENATAL EDCs EXPOSURE

The critical developmental period of the fetus has been demonstrated to exhibit heightened sensitivity to EDCs. According to the DOHaD theory[17], prenatal exposure to EDCs has the capacity to permanently alter the developmental trajectory of offspring’s energy homeostasis through epigenetic reprogramming and disruption of hormonal signalling[20]. This, in turn, has the potential to increase the risk of obesity in later life[20]. It has been established that a number of EDCs [e.g., bisphenol A (BPA), phthalates (PAEs), per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS)] are frequently detected in pregnant women[22] and have the capacity to directly affect the fetus via the placenta[23]. Current research is shifting from single-substance risk assessment to evaluating the effects of mixed exposure[24], while mechanistic studies are expanding beyond organ toxicity to new dimensions such as disruption of the gut microbiota-metabolism axis and transgenerational inheritance[18,20]. Table 1 summarizes key findings on prenatal EDC exposure and childhood obesity risk.

Summary of key epidemiological studies on prenatal exposure to endocrine-disrupting chemicals and childhood obesity risk

| Author (year) | Cohort/Study design | Exposure type | Sample size | Main findings | Conclusion |

| Valvi et al.[33] (2013) | INMA-sabadell birth cohort, Spain | BPA in maternal urine (1st and 3rd trimester) | 402 mother-child pairs | · Prenatal BPA exposure associated with increased waist circumference (β = 0.28 per log10 unit) and BMI (β = 0.28) at age 4 years, but not with rapid growth in infancy | Prenatal BPA exposure may contribute to increased adiposity in early childhood, though not evident in infancy. Urinary BPA variability warrants caution |

| Prospective cohort | |||||

| Braun et al.[51] (2016) | HOME study, Cincinnati, USA | PFOA, PFOS, PFNA, PFHxS in maternal serum | 204 children | · Children in top two PFOA terciles had higher adiposity at age 8 (e.g., waist circumference: 2nd tercile β = 4.3 cm, 3rd tercile β = 2.2 cm) | Prenatal PFOA exposure is associated with increased adiposity and accelerated BMI gain in childhood, particularly at higher exposure levels |

| Prospective cohort | · Faster BMI gain from 2-8 years in higher PFOA exposure groups | ||||

| Warner et al.[47] (2017) | CHAMACOS cohort, Salinas, USA | DDT, DDE in maternal serum | 240 children | · Prenatal DDT/DDE associated with higher BMI z-score in boys (o,p’-DDT: β = 0.37; p,p’-DDT: β = 0.26; p,p’-DDE: β = 0.31) | Prenatal DDT/DDE exposure may increase obesity risk in boys, supporting sex-specific effects of organochlorine pesticides |

| Prospective cohort | · No associations in girls | ||||

| Berger et al.[25] (2021) | CHAMACOS cohort, Salinas, USA | Phthalates, parabens, phenols in maternal urine | 309 children | · MEP, MCNP, propylparaben consistently associated with higher BMI z-score and overweight/obesity risk | Prenatal exposure to phthalates and parabens may increase early childhood obesity risk, highlighting the importance of assessing chemical mixtures |

| Prospective cohort | · Mixture analysis (BHM, BKMR) supported cumulative effect of multiple chemicals | ||||

| Ferguson et al.[26] (2022) | TIDES cohort, USA | Phthalate metabolites in maternal urine | 780 mother-child pairs | · Inverse associations with birth weight-for-length z-scores; positive associations with BMI z-scores at 3-4 years (e.g., MEP: β = -0.17 at birth, +0.18 at 4 years) | Prenatal phthalate exposure is associated with a pattern of low adiposity at birth and higher adiposity in early childhood |

| Multi-center prospective cohort |

Prenatal exposure to PAEs and childhood obesity

The extant epidemiological evidence provides support for the hypothesis of an association between exposure to PAEs during the prenatal period and an increased risk of obesity in offspring. A substantial body of research, including numerous large birth cohort studies[25-27], has demonstrated a robust correlation between prenatal exposure to various PAE metabolites [e.g., monoethyl phthalate (MEP), monocarboxyisononyl phthalate (MCNP)] and elevated childhood body mass index (BMI) z-scores, along with an augmented risk of developing overweight or obesity. This correlation manifests in a dose-response relationship, suggesting that increased exposure levels are associated with greater adverse outcomes. It is noteworthy that this association demonstrates dynamic changes, with certain PAE metabolites correlating with lower birth weight but shifting to higher BMI during childhood[26]. This suggests the potential disruption of normal growth trajectories. However, inconsistencies have been observed across studies, potentially attributable to differences in the study populations, the methods of exposure assessment, and the control of confounding factors[28,29].

The mechanism of action of this substance primarily involves metabolic reprogramming disruption and energy balance disorder. As demonstrated in the relevant animal studies[30], low-dose di-n-butyl phthalate (DBP) exposure during pregnancy has been shown to induce endoplasmic reticulum stress. This, in turn, has been found to suppress the expression of Uncoupling Protein 1 (UCP1), a key thermogenic protein in brown adipose tissue, and to reduce the basal metabolic rate. This results in obesity phenotypes in offspring, characterized by fat accumulation and abnormal glucose and lipid metabolism. However, this effect can be reversed by endoplasmic reticulum stress inhibitors. Conversely, certain polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) [e.g., dibenzo[a,h]pyrene (DiBP)] act as agonists of the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARγ), activating adipogenesis-related pathways to promote adipocyte differentiation and lipid storage[31]. These findings reveal, from an epidemiological to a mechanistic level, the potential role of PAEs as significant environmental obesogens that program offspring obesity susceptibility through multiple biological pathways.

Prenatal exposure to bisphenol and childhood obesity

Prenatal exposure to BPA and its substitutes [e.g., bisphenol F (BPF)] has been demonstrated to manifest complex dose-response and sex-specific patterns in relation to the risk of childhood obesity. The extant epidemiological evidence indicates that early-life exposure to BPA may result in the disruption of endocrine homeostasis and fat metabolism programming, consequently augmenting the risk of obesity in offspring. A 2024 systematic review[32] noted that, among 13 cohort studies, eight found elevated prenatal urinary BPA levels to be positively correlated with childhood obesity indicators, such as BMI z-score, waist circumference, and skinfold thickness. The strongest associations were observed in girls[33-35]. The Wuhan Birth Cohort Study in China also found that exposure to BPA and BPF during the mid- and late-pregnancy periods was significantly associated with a “low-start-rapid-growth” BMI trajectory in offspring under two years of age, suggesting their impact on early weight gain patterns[36]. However, a number of studies[37-39] have failed to identify significant positive associations, and indeed, some have even reported negative correlations, thus highlighting significant inconsistencies in the current evidence. These discrepancies may be attributable to factors such as study design, exposure windows, and population heterogeneity.

At the mechanistic level, prenatal bisphenol exposure has the capacity to influence offspring obesity risk through multiple pathways, including, but not limited to, epigenetic regulation, placental metabolic programming, and nuclear receptor disruption. The results of animal studies suggest that exposure to low-dose BPA during pregnancy can be transmitted via fat-derived extracellular microRNAs (miRNAs) such as miR-124-3p. This exposure has been shown to suppress the expression of the nuclear receptor PPARγ and to reduce the activity of the fibroblast growth factor 21 (FGF21) and the phosphoinositide-dependent protein kinase B (p-AKT). This results in hepatic insulin resistance and lipid accumulation, with the mechanism being particularly pronounced in male offspring[40]. BPA has been demonstrated to disrupt placental energy metabolism by upregulating the expression of glucose transporter 1 (Glut1). This, in turn, has been shown to cause placental glucose and glycerophospholipid metabolism disorders, ultimately resulting in impaired glucose tolerance in female offspring[41]. It is important to note that the effects of bisphenol compounds vary depending on the specific compound in question. For instance, exposure to Bisphenol AF (BPAF) has been shown to enhance insulin sensitivity in male offspring[42], indicating that the specific compound, sex, and epigenetic modification status collectively determine the final metabolic phenotype.

Prenatal exposure to pesticides, herbicides and insecticides and childhood obesity

Prenatal exposure to organochlorine pesticides, particularly dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT) and its primary metabolite dichlorodiphenyldichloroethylene (DDE), has been demonstrated to be associated with the development of obesity in offspring, although the observed effects exhibit both compound specificity and gender differences. A substantial number of prospective studies[43] have identified prenatal p,p’-DDE (1,1-dichloro-2,2-bis(p-chlorophenyl)-ethylene) exposure as a risk factor for childhood overweight, obesity, and diabetes development. For instance, a Spanish birth cohort study of 1,361 newborns[44] found that prenatal exposure to DDE and hexachlorobenzene (HCB) was positively associated with accelerated growth during the first six months postnatal and increased risk of overweight at 14 months, with DDE’s effect on accelerated growth being more pronounced in males. Converging conclusions were ascertained from studies conducted in the Faroe Islands[45] and Belgium[46]. However, the U.S. Center for the Health Assessment of Mothers and Children of Salinas (CHAMACOS) study[47] demonstrated that DDT/DDE exposure exhibited an association solely with BMI in male subjects. Conversely, a Chinese longitudinal study encompassing 98 mother-infant pairs[48] identified elevated p,p’-DDE concentrations as being associated with diminished BMI Z-scores, thereby signifying discrepancies in the findings of research studies.

The mechanism of action of this substance primarily involves the disruption of energy metabolism and epigenetic programming. As demonstrated in the relevant animal studies[49], prenatal DDT exposure has been shown to have a significant impact on energy expenditure and thermoregulatory capacity in offspring, particularly in female subjects. The research indicates that this exposure reduces thermogenesis and predisposes individuals to greater fat accumulation later in life, thereby increasing the risk of obesity and associated metabolic syndromes. Recent research has also revealed novel mechanisms by which pesticides may influence offspring through epigenetic modifications[50]. For instance, prenatal exposure to the fungicide imazalil during pregnancy induced disorders in hepatic glucose and lipid metabolism in both maternal mice and their offspring, showing a strong correlation with abnormal N6-methyladenosine (m6A) RNA methylation. This provides new evidence that environmental pollutants may affect metabolic health through transgenerational epigenetic programming[50]. These findings suggest that prenatal exposure to pesticides may program offspring obesity risk through multiple mechanisms, including the disruption of key metabolic pathways and the induction of epigenetic alterations.

Prenatal exposure to PFAS and childhood obesity

The correlation between prenatal exposure to PFAS during pregnancy and the subsequent risk of obesity in offspring has been substantiated by numerous prospective studies. The 2016 U.S. HOME cohort study[51] demonstrated a significant positive correlation between maternal serum perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) concentrations during pregnancy and children’s obesity levels at age 8. Another study[52] found that higher maternal serum perfluoroundecanoic acid (PFUnDA) concentrations in non-obese women were associated with increased waist circumference, fat mass, and body fat percentage in offspring. A 2018 Norwegian and Swedish cohort study[53] followed 412 mother-infant pairs over a period of five years and similarly demonstrated a positive correlation between maternal serum PFAS concentrations and offspring overweight/obesity risk. It is important to note that PFAS can cross the placenta and enter breast milk, exerting persistent effects on developing fetuses and infants, thereby increasing potential health risks from early-life exposure[54].

With regard to the mechanism of action, PFAS have been shown to program offspring obesity risk by interfering with placental function, affecting adipocyte differentiation, and disrupting metabolic homeostasis. A plethora of studies[55,56] have indicated that exposure to perfluorooctane sulfonic acid (PFOS) has the capacity to significantly disrupt the process of placental nutrient transport, induce fetal growth restriction, and lead to long-term alterations in offspring liver lipid metabolism gene expression profiles and gut microbiota. PFOS has been demonstrated to disrupt adipocyte differentiation by inhibiting pivotal metabolic enzyme activity, thus facilitating adipose tissue accumulation[57]. These findings suggest that prenatal exposure to PFAS may increase the susceptibility of offspring to metabolic disorders through multiple synergistic biological pathways, thereby laying the groundwork for future obesity development.

Prenatal exposure to pharmaceuticals and personal care products and childhood obesity

The association between prenatal exposure to pharmaceuticals and personal care products (PPCPs) and offspring obesity risk exhibits compound specificity and complex effects. Prenatal exposure to parabens has been demonstrated to be a significant contributing factor to the increased risk of early childhood obesity, as indicated by epidemiological studies. The CHAMACOS cohort study[25] established that prenatal phthalate exposure was associated with increased obesity risk in 5-year-old children. The German LINA (Lifestyle and environmental factors and their Influence on Newborns Allergy risk) cohort study[58] further confirmed that maternal exposure to butyl phthalate during pregnancy was significantly associated with offspring overweight risk during the first eight years of life, with a stronger effect observed in female offspring. However, it should be noted that not all PPCPs have been observed to induce pro-obesity effects. A large retrospective study[59] involving over 53,000 mother-infant pairs demonstrated no significant association between outpatient antibiotic use during pregnancy and offspring BMI z-scores at age 5, suggesting that different categories of PPCPs may have varying impacts on offspring obesity risk.

As indicated by research on the mechanism of action[60], the presence of PPCPs can program offspring obesity risk through multiple pathways, including the disruption of endocrine homeostasis, the effect on fat programming, and the influence on the development of metabolic organs. However, it should be noted that these effects are highly dependent on the type of compound, the exposure window, and the dose. It is well established that common medications such as acetaminophen have the potential to disrupt metabolic programming by interfering with the fetal endocrine system. Conversely, recent studies have identified the potential of newer-generation hypoglycemic and weight-loss drugs, such as glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists (e.g., semaglutide), to improve the maternal metabolic environment and potentially reduce the risk of offspring obesity when used in preconception interventions[61]. A recent animal study[62] confirmed that the preconception use of semaglutide improves high-fat diet-induced metabolic abnormalities in a sex-specific manner. This phenomenon is mediated through the regulation of placental function, as evidenced by enhanced expression of the amino acid transporters solute carrier family 38 member 1 (Slc38a1) and member 2 (Slc38a2). Additionally, fetal hypothalamic appetite control centers are restored, as demonstrated by the normalization of leptin signaling and the rebalancing of Pro-opiomelanocortin (POMC)/Agouti-related peptide (AGRP) neuropeptide expression. These findings underscore the complexity and bidirectional nature of PPCP interference with offspring energy metabolism, with net effects contingent on specific pharmacological properties, target interactions, and developmental timing.

PRENATAL EXPOSURE TO AIR POLLUTANTS

As global air pollution continues to worsen, recent studies have found that exposure of the mother to pollutants such as particulate matter (PM), nitrogen oxides (NOX), carbon oxides (COX), sulfur oxides (SOX), and ozone (O3) during pregnancy may significantly increase the risk of obesity in offspring[63,64]. However, atmospheric pollutants are characterized by a high degree of complexity. For instance, PM exhibits significant variation in its biological effects, depending on its size (e.g., PM1, PM2.5, PM10). Furthermore, the critical exposure windows for different pollutants exhibit heterogeneity, and synergistic or antagonistic interactions may occur among multiple pollutants. These factors have resulted in the identification of inconsistent conclusions regarding exposure-outcome associations in extant studies, thus rendering pollutant-specific health impact mechanisms a focal point of environmental health research recently. Major studies on prenatal air pollutant exposure and offspring obesity are consolidated in Table 2.

Summary of key epidemiological studies on prenatal exposure to air pollution and childhood obesity risk

| Author (year) | Cohort/Study design | Exposure type | Sample size | Main findings | Conclusion |

| Fleisch et al.[84] (2015) | Project Viva, Boston, USA | Black Carbon, PM2.5, Traffic density, Roadway proximity | 2,115 mother-child pairs | · Highest quartile of traffic density associated with: - Reduced fetal growth (β = -0.13 z-score) - More rapid 0-6 months weight-for-length gain (β = 0.25 z-score) - Higher odds of high adiposity at 6 months (OR = 1.84) | Infants exposed to higher traffic-related pollution in early life may exhibit more rapid postnatal weight gain in addition to reduced fetal growth |

| · The combination of low fetal growth + rapid infant gain was 3 times more likely (OR = 3.01) in high traffic exposure group | |||||

| Chiu et al.[65] (2017) | ACCESS cohort, Boston, USA | PM2.5 | 239 children | · Sex-specific associations were found: - Boys: Increased PM2.5 exposure at 8-17 weeks gestation was associated with higher BMI-z; at 15-22 weeks with higher fat mass (kg) - Girls: Increased PM2.5 exposure at 10-29 weeks gestation was associated with higher waist-to-hip ratio | Prenatal PM2.5 exposure was associated with increased whole-body size in boys and a central adiposity pattern in girls, indicating sex-specific critical windows of susceptibility |

| Alderete et al.[75] (2018) | Pediatric obesity maternal and child health study (MACHS), Los Angeles, USA | Traffic-related air pollution (TRAP): · Non-freeway NOx · Distance to major roadways · CALINE4 model for NOx | 136 mother-infant pairs | · 1-SD ↑ in non-freeway NOx (2 ppb): associated with 33% higher leptin (P = 0.01) and 9% higher HMW adiponectin (P = 0.07) | Prenatal TRAP exposure is associated with altered cord blood adipokine levels (leptin and HMW adiponectin), which may contribute to sex-specific infant weight gain and future obesity risk, especially in females |

| 46 with 6-month follow-up | · Living < 75 m vs. > 300 m from major roadways: 71% higher leptin (P = 0.03) | ||||

| · 1-SD ↑ in leptin (10 ng/mL): associated with 0.62 kg weight gain in female infants (P = 0.02), not males | |||||

| Ambient: NO2, O3, PM2.5, PM10 | |||||

| Tan et al.[90] (2021) | Population-based prospective birth cohort, Wuhan, China | PM10, SO2, NO2, CO, O3 | 62,540 mother-child pairs | · PM10, CO ↑: associated with higher risk of slow growth trajectory | Prenatal exposure to high levels of air pollutants is associated with deviations in childhood BMI growth trajectories from birth to 6 years |

| · NO2 ↑: associated with higher risk of both slow and rapid growth | |||||

| · SO2 ↑: associated with rapid growth trajectory | |||||

| · O3 ↑: associated with lower risk of rapid growth | |||||

| · Stronger associations were observed in girls, rural children, and those with normal-weight mothers | |||||

| Bloemsma et al.[80] (2022) | Healthy start study, Colorado, USA | PM2.5, O3, Traffic proximity and density | 738 children | · 2nd trimester PM2.5 ↑: associated with higher % fat mass and FMI | Limited evidence for associations with PM2.5 and O3, which were inconsistent across trimesters. Suggestive evidence that living near a highway during pregnancy may increase childhood obesity risk |

| · 3rd trimester PM2.5 ↑: associated with lower % fat mass and FMI | |||||

| · Residential proximity to a highway: associated with higher odds of overweight (OR = 2.26 for closest vs. farthest) | |||||

| · No consistent associations with O3 or traffic density |

Prenatal exposure to PM and childhood obesity

Prenatal exposure to atmospheric PM has been demonstrated to be significantly associated with an increased risk of childhood obesity, exhibiting distinct sex-specific sensitive windows and particle size effects. The Asthma Coalition on Community, Environment and Social Stress (ACCESS) cohort study, conducted in the city of Boston in the United States of America[65], utilized a high spatiotemporal resolution PM2.5 model and a Bayesian Distributed Lag Interaction Model (BDLIM) to ascertain that, for male subjects, a 1 μg/m3 increase in PM2.5. Exposure during weeks 8-17 of gestation was associated with a cumulative increase in BMI z-score of 0.21. In contrast, exposure during weeks 10-29 was associated with a 0.02 increase in waist-to-hip ratio in girls. This finding suggests a heightened risk of systemic obesity in boys, in contrast to the predominance of central obesity in girls. Further studies have indicated a correlation between PM10 and PM2.5 with augmented umbilical circumference and subcutaneous fat thickness, respectively[66], with early-life exposure being associated with minor BMI increases, particularly during the initial two postnatal months[67]. It is noteworthy that PM exposure exerts a differential influence on childhood weight trajectories by sex. Specifically, female children who are exposed to elevated levels of PM2.5 (greater than 9.5 μg/m3) demonstrate a tendency towards higher body weights, while male children exhibit a significantly lower body weight tendency. Furthermore, female children with low birth weight demonstrate heightened sensitivity to PM2.5 effects[68].

The mechanisms by which PM exposure contributes to offspring obesity primarily relate to its physical properties and the series of physiological and pathological responses it triggers. As a suspension of solid and liquid matter, PM toxicity is inversely correlated with particle size; smaller particles (e.g., PM1, PM2.5) possess a significantly larger surface area per unit volume, enabling more efficient adsorption of toxic compounds. These particles have the potential to breach the blood-gas barrier, thereby gaining entry into the circulatory system and inducing multi-organ toxicity[69]. Prenatal exposure to PM has been demonstrated to heighten the risk of obesity in offspring through three principal mechanisms: (i) elevation of umbilical cord adiponectin levels[70]; (ii) disruption of mitochondrial energy metabolism and lipid homeostasis in white adipose tissue[71,72]; and (iii) activation of chronic inflammatory responses and nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2)-mediated dysregulation of lipogenic enzymes[71]. These pathways collectively lead to the epigenetic reprogramming of fetal metabolic development. Evidence[73,74] indicates that prenatal PM2.5 exposure specifically increases DNA methylation of the leptin gene promoter in adipocytes of male offspring, thereby suppressing leptin secretion, disrupting energy balance regulation, and ultimately leading to increased food intake and heightened susceptibility to obesity. In contrast, in female offspring, the same exposure appears to preferentially alter the hepatic lipid metabolism program, manifesting as abnormal increases in hepatic lipid accumulation and downregulation of genes involved in fatty acid metabolism (e.g., liver fatty acid-binding protein 1), presenting a distinct metabolic disturbance phenotype. These sex-specific epigenetic reprogramming events may originate from divergent placental responses to oxidative stress, inflammatory status, and adaptive epigenetic regulation following exposure, thereby establishing different gendered patterns of susceptibility to obesity in later life.

Prenatal exposure to NOx and childhood obesity

Prenatal exposure to NOx, particularly NOx from traffic-related air pollution, has been demonstrated to be associated with an increased risk of obesity in offspring. The potential mediation of this effect by influencing adipokine levels and inducing metabolic disorders is a hypothesis that merits further investigation. A study by Alderete et al. demonstrated that prenatal NOx exposure was significantly associated with elevated levels of leptin and high-molecular-weight adiponectin in umbilical cord blood[75]. Specifically, an increase of one standard deviation (SD) in NOx was found to be associated with a 33% increase in cord blood leptin levels and a 9% increase in high-molecular-weight adiponectin. It is noteworthy that this association manifested sex differences, with elevated leptin levels exhibiting a significant correlation with weight gain within the first six months postnatal in female infants, while no such association was observed in male infants[75]. Another large-scale study[76] based on cohort data from over 474,000 Israeli infants found that a 7.3 ppb increase in prenatal NO2 exposure was associated with a cumulative risk ratio of 1.02 for childhood obesity. Moreover, research indicates that exposure to NO2 in the early stages of life is associated with a slight increase in BMI before the age of five, with the strongest association occurring within the first two months after birth. This suggests that NO2 may influence early-life BMI growth through interactions with other urban environmental exposures[67].

The potential mechanisms by which NOx increases the risk of childhood obesity involve multiple pathways[77]. As demonstrated in the research conducted by Nadif et al., exposure of the mother to NOx during pregnancy has been shown to increase the risk of excessive weight gain in the mother, as well as to elevate the levels of biomarkers such as leptin and insulin in the umbilical cord blood of the fetus[78]. Such hormonal alterations have been demonstrated to promote fetal overgrowth and the occurrence of macrosomia. At the molecular level, NO2, when present as part of air pollutant mixtures, has been observed to exacerbate metabolic disorders by promoting systemic inflammation and oxidative stress[79]. In particular, exposure to NO2 has been demonstrated to elevate inflammatory markers [e.g., monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1), serum amyloid A (SAA)] with the resultant activation of immune responses, whilst simultaneously disrupting lipid metabolism. This phenomenon is primarily characterized by the enhancement of endogenous lipogenesis pathways, leading to an increase in triglycerides (TGs) and a decrease in high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C). Consequently, this contributes to the exacerbation of obesity-related lipid metabolism abnormalities[79]. Collectively, these mechanisms enhance the propensity of offspring to develop obesity in later life through alterations in fetal metabolic programming and the establishment of energy balance.

Prenatal exposure to O3 and childhood obesity

The association between prenatal exposure to O3 during pregnancy and the subsequent risk of obesity in offspring exhibits complex time-specificity and heterogeneity in its effect, with the impact being highly dependent on the specific gestational stage during which exposure occurs. The extant research suggests that exposure to O3 during the first and last trimesters of pregnancy may engender divergent effects on childhood obesity indicators. Bloemsma et al. discovered that exposure to O3 during the early stages of pregnancy was associated with a reduced body fat percentage in children aged between 4 and 6 years[80]. Conversely, exposure during the latter stages of pregnancy was linked to an increased body fat percentage. These findings suggest the presence of critical exposure windows during which the effects may be particularly significant. Furthermore, Sun et al. conducted a large-scale nationwide study that revealed significant associations between prenatal O3 exposure and fetal growth restriction[81]. Each 10 ppb increase in O3 exposure during weeks 13-25 of gestation was associated with an average reduction of 7.6 grams in full-term birth weight and a 3% increased risk of full-term infants with a small-for-gestational-age (SGA). It is noteworthy that these associations were more pronounced among non-Hispanic Black individuals and mothers who were either unmarried or had attained a lower level of education. The findings suggest that O3 may trigger a “thrifty phenotype” adaptation by inhibiting fetal growth, leading to postnatal catch-up growth and increased long-term obesity risk.

The mechanisms underpinning this phenomenon have been linked to O3-induced oxidative stress, metabolic reprogramming alterations, and epigenetic modifications. The results of animal studies indicate that exposure to O3 during the early stages of pregnancy has a significant impact on energy metabolism in mice. Specifically, the exposure enhances the dependence of mice on branched-chain amino acid energy production, induces elevated corticosterone levels, and strengthens the reliance of offspring on fatty acid energy. These effects ultimately contribute to the development of obesity in the offspring[82]. In contrast, exposure to O3 during the late stages of pregnancy exerts its effects through epigenetic mechanisms. It has been demonstrated that maternal exposure during this period can lead to alterations in the methylation levels of several genes, including histone deacetylase 4 (HDAC4), prolactin-releasing hormone receptor (PRLHR), tenascin XB (TNXB), and positive regulatory domain-containing 16 (PRDM16). This conclusion is supported by evidence from studies of umbilical cord blood[83]. These alterations have been shown to trigger inflammatory responses and metabolic dysregulation. Collectively, these findings suggest that O3 may suppress fetal growth by inducing oxidative stress and placental dysfunction. In addition, it may influence long-term obesity risk in offspring by programmatically altering energy metabolism pathways and inflammatory states. However, the current evidence linking O3 exposure to childhood obesity remains limited in scope, necessitating further research to validate its sensitive windows and underlying mechanisms.

Prenatal exposure to COx and childhood obesity

Prenatal exposure to COx, primarily from traffic-related pollutants, has been demonstrated to be strongly associated with fetal growth restriction and an increased risk of obesity later in life. Fleisch et al. found that prenatal exposure to traffic pollutants - such as black carbon and PM2.5 - was significantly associated with fetal growth restriction and accelerated weight gain in infancy[84]. This was manifested as faster weight-for-length z-score growth from 0 to 6 months of age and an 84% increased risk of being in the ≥ 95th percentile for weight-for-length at 6 months. The present study hypothesizes that prenatal exposure to air pollutants may induce a “thrifty phenotype” in fetuses, characterized by fetal growth restriction followed by catch-up growth in infancy. This is postulated to occur through the mechanisms of oxidative stress and inflammation, which have been demonstrated to increase the risk of future cardiovascular and metabolic diseases[84]. Guo et al. further confirmed that exposure to environmental CO during pregnancy is significantly associated with fetal growth restriction[85]. Each increase in the interquartile range (IQR) of CO concentration has been shown to correlate with reduced birth weight, with more pronounced effects observed during the periods of mid-to-late pregnancy. This suggests the potential for CO exposure to disrupt the oxygen supply to the fetus through placental toxicity.

Its mechanisms involve multiple pathways. Studies indicate that COx crosses the placental barrier from maternal to fetal circulation[86], elevating umbilical cord blood levels of leptin and adiponectin and altering metabolic programming during fetal development[84,87,88]. Specifically, CO binds to hemoglobin to form carboxyhemoglobin, reducing oxygen transport capacity and triggering fetal hypoxia stress[89]. Concurrently, COx exposure induces oxidative stress and inflammatory responses, disrupting placental nutrient transport and altering fetal energy metabolism programming[86]. These combined alterations result in intrauterine growth restriction and postnatal metabolic adaptations, programming offspring susceptibility to obesity and laying the foundation for infantile and childhood obesity.

Prenatal exposure to SOx and childhood obesity

Prenatal exposure to SOX (primarily SO2) has been demonstrated to be significantly associated with an increased risk of childhood obesity in offspring. For instance, Tan et al. conducted a large-scale birth cohort study and found that prenatal exposure to higher concentrations of SO2 during pregnancy was significantly associated with childhood obesity risk [odds ratio (OR) = 1.070, 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.044-1.096][90]. Subgroup analyses by gender and region revealed that this association was more pronounced among boys and rural children. This study suggests that SO2 may increase the risk of childhood obesity by disrupting normal fetal metabolic development, highlighting the potential long-term growth impacts of prenatal SOx pollution on offspring[90].

The mechanism of action of this substance primarily involves synergistic effects with other air pollutants (e.g., NO2, PM2.5), which serve to indirectly promote metabolic abnormalities by inducing chronic inflammation and vascular dysfunction[91]. Zhang et al. demonstrated that co-exposure to SO2, NO2, and PM2.5 induces chronic low-grade inflammation by upregulating pro-inflammatory factors[91]. Specifically, cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2), inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS), tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), and interleukin (IL)-6 act synergistically to increase endothelin-1 (ET-1) expression and suppress endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS), leading to vascular endothelial dysfunction and myocardial mitochondrial structural damage and oxidative stress[91]. Collectively, these pathological alterations disrupt metabolic homeostasis and cardiovascular function, potentially indirectly promoting obesity-related metabolic abnormalities and subsequent disease progression. However, the prevailing focus of contemporary research is predominantly on SO2, with a paucity of research addressing the association between other SOx compounds (e.g., SO3) and offspring obesity. Further studies are required to explore their health effects and underlying mechanisms.

PRENATAL ENDOCRINE AND METABOLIC ABNORMALITIES

Maternal endocrine and metabolic abnormalities during pregnancy - including excessive gestational weight gain (GWG), hyperglycemia, and dyslipidemia - have been demonstrated to exert a significant influence on offspring adipose tissue development and future obesity risk through multiple mechanisms[92]. A mounting body of fundamental and clinical research suggests that maternal obesity and associated metabolic disorders enhance fetal nutrient uptake via placental transport, thereby inducing excessive differentiation of fetal preadipocytes and developmental reprogramming of the trophoblast[93]. Moreover, it has been demonstrated that maternal metabolic dysregulation can trigger low-grade intrauterine inflammation, oxidative stress responses, and epigenetic regulatory alterations. Collectively, these factors contribute to structural remodeling of adipose tissue and adaptive changes in energy metabolism within the offspring phenotype[94,95]. It is well established that these biological processes frequently manifest during the neonatal period as excessive fat accumulation, abnormal adipocyte numbers, or phenotypic reconfiguration. This provides a foundation for the subsequent development of obesity. Table 3 provides a summary of maternal metabolic abnormalities associated with increased childhood obesity risk.

Summary of key epidemiological studies on prenatal endocrine and metabolic abnormalities and childhood obesity risk

| Author (year) | Cohort/Study design | Exposure type | Sample size | Main findings | Conclusion |

| Liu et al.[111] (2016) | Retrospective cohort study, China | Early pregnancy fasting plasma glucose (FPG) and triglyceride levels | 1,546 mother-child pairs | · First Visit FPG and mid-pregnancy triglyceride levels were positively associated with neonatal birth weight, head circumference, and shoulder circumference | Fasting blood glucose levels at the first prenatal visit are unrelated to mid-pregnancy lipid concentrations, but may jointly influence fetal growth and development alongside triglyceride levels |

| · No association between First Visit FPG and mid-pregnancy lipid profiles | |||||

| Christensen et al.[112] (2016) | Prospective cohort (Stork Study), Norway | Maternal LDL cholesterol in early pregnancy | 61 mother-child pairs (27 high LDL, 34 low LDL) | · Offspring of mothers with high LDL-C (≥ 90th percentile) had 0.4 mmol/L higher LDL-C at age 6-13 years | Maternal hypercholesterolemia in early pregnancy is associated with higher offspring LDL-C in childhood, suggesting a potential early-life determinant of cardiovascular risk |

| · No differences in birth weight, BMI, blood pressure, or other CVD risk factors between groups | |||||

| Voerman et al.[96] (2019) | Individual participant data meta-analysis of 37 cohorts from Europe, North America, Australia | Maternal pre-pregnancy BMI and gestational weight gain | 162,129 mother-child pairs | Higher maternal BMI and gestational weight gain were associated with increased risk of offspring overweight/obesity, with stronger effects in late childhood. Population attributable risk for maternal overweight/obesity was 10%-22% | Maternal pre-pregnancy BMI is a major modifiable risk factor for childhood obesity, with gestational weight gain having a smaller additional effect |

| Øyri et al.[109] (2023) | Parental negative control study (MoBa, Norway) | Maternal prenatal cholesterol levels | 713 mother-father-child trios | Maternal total cholesterol was positively associated with offspring weight gain up to age 8. Maternal HDL-C and apoA1 were negatively associated. Paternal cholesterol showed weaker or inconsistent associations | Maternal prenatal cholesterol levels may directly influence offspring weight trajectory via intrauterine mechanisms, independent of shared genetics or environment |

| Deng et al.[102] (2025) | Prospective cohort (HAPO Hong Kong) | Maternal overweight and GDM | 564 mother-child dyads | Combined maternal overweight and GDM was associated with a 6.90-fold increased risk of rapidly increasing adiposity trajectory from birth to early adolescence (age 9-14) | Maternal overweight and GDM have independent and joint effects on offspring adiposity trajectories, highlighting the need for combined metabolic risk assessment |

Prenatal overweight/obesity and childhood obesity

Substantial epidemiological evidence indicates that maternal pre-pregnancy overweight/obesity and excessive weight gain during pregnancy significantly increase the risk of childhood and adolescent obesity in offspring. A meta-analysis encompassing over 160,000 mother-child pairs demonstrated that maternal pre-pregnancy overweight or obesity is associated with a markedly elevated risk of offspring developing overweight/obesity across various growth stages, exhibiting a consistent positive correlation[96]. A further systematic review[97], incorporating 11 cohort studies (involving 27,505 mother-child pairs), has corroborated the hypothesis that there is a consistent positive correlation between pre-pregnancy overweight/obesity and childhood obesity. It is noteworthy that in the United States, a high proportion of low-income minority populations exhibit a significantly elevated risk of their offspring becoming obese or overweight before adolescence, a phenomenon that has been attributed in part to the influence of maternal pre-pregnancy overweight/obesity[98]. This observation lends support to the hypothesis that socioeconomic factors may play a pivotal role in amplifying the impact of environmental influences on the development of obesity in offspring[98].

Its mechanism of action involves alterations to metabolic reprogramming at multiple levels[99]. The results of studies using animal models[99] indicate that maternal obesity can lead to the premature initiation of fetal adipogenesis. This, in turn, can result in the abnormal expansion of the fetal fat progenitor cell pool and the hypertrophy of fat cells in late gestation. Consequently, this can accelerate postnatal fat accumulation. Concurrently, maternal obesity has been demonstrated to alter the development of the hypothalamic appetite control center in offspring, manifesting as enhanced pro-appetite signaling and impaired anorexigenic neural pathways, resulting in postnatal hyperphagia and weight gain[100]. Recent studies[101] have revealed that maternal obesity can induce epigenetic alterations in fetal DNA methylation and histone modifications. These modifications persist into adulthood, affecting the expression of energy metabolism-related genes and thereby increasing offspring susceptibility to obesity. Collectively, these mechanisms elucidate how maternal overweight/obesity during pregnancy significantly increases offspring obesity risk by promoting fetal fat development, reprogramming the hypothalamic appetite center, and inducing persistent epigenetic alterations.

Prenatal hyperglycemia and childhood obesity

A hyperglycemic environment during pregnancy, encompassing both gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) and subclinical glucose abnormalities below diagnostic thresholds, has been demonstrated to be a significant determinant of offspring obesity risk in the long term. The hypothesis is further substantiated by the findings of large-scale prospective cohort studies. For instance, data from the Hong Kong Hyperglycemia and Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes (HAPO) study[102] revealed that combined maternal overweight and GDM exposure significantly increased offspring risk of rapid obesity trajectory from birth to early adolescence (9-14 years) (OR = 6.90). Isolated GDM exposure was also found to elevate risk by 2.95-fold, with the combined exposure group exhibiting the fastest annual subcutaneous fat accumulation rate. Long-term follow-up data (18 years) further confirmed that for every 1.58 mmol/L (1 SD) increase in maternal 1 h glucose during pregnancy, the offspring’s risk of overweight/obesity at age 18 increased by 50%, exhibiting a continuous dose-response relationship[103]. This finding indicates that even in cases where glucose levels are below the threshold for a diagnosis of GDM, there remains a risk to the patient. It is important to note that medical interventions may offer a partial mitigation of adverse effects. A cohort study[104] following China’s two-child policy found that standardized prenatal care and lifestyle interventions weakened the association between GDM and offspring long-term obesity.

The core mechanism underpinning this phenomenon involves maternal hyperglycemia-induced placental dysfunction and fetal metabolic adaptation[105]. Maternal hyperglycemia has been demonstrated to result in elevated glucose transport across the placenta, thereby inducing fetal hyperinsulinemia[106]. The placental structure of GDM mothers undergoes significant alterations, including thickening of the syncytiotrophoblast basement membrane, villous edema, and cellular hyperplasia. Collectively, these changes have been shown to impair nutrient and oxygen exchange efficiency, thereby exacerbating fetal metabolic stress[106]. Furthermore, the hyperglycemic environment has been demonstrated to elevate placental oxidative stress levels. Increased reactive oxygen species (ROS) have been shown to induce mitochondrial dysfunction and lipid peroxidation, which in turn trigger the release of inflammatory mediators such as TNF-α and IL-6[106]. Recent research[107] further reveals that progesterone regulates maternal insulin sensitivity via the membrane progesterone receptor ε (mPRε) in white adipose tissue, ensuring efficient glucose transport to the fetus. This pathway is of critical importance in the context of nutrient allocation. Importantly, GDM pregnancies encompass a spectrum of fetal growth outcomes, including both macrosomia and, in cases of concomitant placental insufficiency, SGA infants[106]. This latter scenario engages the “Thrifty Phenotype” hypothesis, wherein the fetus adapts to a limited nutrient supply by programming a metabolism optimized for energy conservation and storage[105]. A subsequent mismatch with a nutritionally abundant postnatal environment then predisposes the SGA offspring to central adiposity and metabolic disease[105]. Collectively, GDM co-programs offspring obesity susceptibility through the interplay of nutrient oversupply, oxidative stress, inflammatory responses, and hormonal signaling pathways.

Prenatal dyslipidemia and childhood obesity

The association between elevated maternal lipid levels during pregnancy and offspring obesity risk has emerged as a research focus in recent years. However, the strength and consistency of the evidence remains weaker in comparison to that relating to hyperglycemia. A multitude of cohort studies[108] have indicated that particular forms of maternal dyslipidemia may exert influence on fetal development through a variety of mechanisms, thereby programming long-term obesity risk in offspring. A large-scale study based on the Norwegian Mother and Child Cohort[109] found that elevated maternal total cholesterol (TC) levels were positively correlated with offspring weight gain from six weeks postnatal to age eight. Another prospective study[110] indicated that increased maternal TGs and free fatty acid (FFA) levels during pregnancy were associated with higher childhood liver fat content in offspring. Liu et al. also found that neonatal growth indicators, such as birth weight, head circumference, and shoulder circumference, were independently associated with mid-pregnancy TG concentrations[111]. However, conclusions in this field are not entirely consistent; for example, Christensen et al. did not observe significant differences in offspring BMI between ages 6 and 13 associated with high maternal low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) during pregnancy[112]. To summarize, the majority of studies demonstrate that maternal dyslipidemia during pregnancy (particularly elevated TG and TC) constitutes a risk factor for childhood obesity. However, further validation is required to ascertain the causal relationship and specific mechanisms through large-scale prospective studies.

Its mechanism of action primarily revolves around the placenta’s processing and transport of lipids. The process of hydrolysis of maternal TGs into FFAs is mediated by lipoprotein lipase (LPL). These FFAs enter the placenta via either fatty acid transporters or the fatty acid translocator (CD36)[113,114]. Insulin activates insulin receptors on the maternal side of syncytiotrophoblast cells, inducing the re-esterification of FFAs into TGs for storage via the protein kinase B (AKT) signaling pathway[113]. FFAs released from the hydrolysis of these TGs can diffuse into the fetal circulation, thereby providing an energy source for the fetus. It is a well-documented fact that pregnant women who are overweight or obese often exhibit insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia. These factors can induce the placenta to store large amounts of TGs. The hydrolysis of these TGs produces excessive FFAs that are transported to the fetus, constituting a partial mechanism by which maternal hypertriglyceridemia increases the risk of macrosomia[113,114]. Furthermore, HDL-C has been demonstrated to play a crucial role in cholesterol reverse transport and homeostasis. As demonstrated in the relevant animal studies[115,116], maternal HDL-C appears to play a significant role in the regulation of fetal metabolism and growth. In models of mice deficient in HDL-C, compensatory increases in placental sterol synthesis or altered metabolism permit greater cholesterol transport to the fetus, potentially explaining the association between low HDL-C and macrosomia.

PRENATAL UNHEALTHY LIFESTYLE

Unhealthy lifestyles during pregnancy, as significant early-life environmental exposures, disrupt metabolic programming in offspring through multiple biological pathways, thereby increasing their long-term risk of obesity[117-119]. Behavioral factors such as maternal tobacco exposure, an unhealthy diet, physical inactivity, and chronic psychological stress affect fetal development independently; however, they also frequently interact synergistically to influence placental function and the regulation of fetal energy balance[120]. Research indicates that these factors can alter the efficiency with which the placenta transports nutrients, induce oxidative stress and inflammatory responses, and regulate gene expression related to adipogenesis through epigenetic modifications. This reshapes the weight set points of offspring[121]. Fetal sex may modulate the metabolic effects of adverse exposures, suggesting biological heterogeneity in these mechanisms[120]. The following sections will examine the associations between specific lifestyle factors, such as maternal tobacco exposure and dietary patterns during pregnancy, and offspring obesity risk, along with their potential underlying mechanisms. Key evidence regarding prenatal unhealthy lifestyle factors and offspring obesity is summarized in Table 4.

Summary of key epidemiological studies on prenatal unhealthy lifestyle and childhood obesity risk

| Author (year) | Cohort/Study design | Exposure type | Sample size | Main findings | Conclusion |

| Koshy et al.[124] (2011) | Community-based cross-sectional survey, Merseyside, UK | Maternal smoking during pregnancy | 3,038 children | · Heavy maternal smoking (> 10 cig/day) associated with higher prevalence of childhood overweight (31.5%), obesity (15.6%), and short stature (5.5%) | Maternal smoking during pregnancy is associated with increased risks of childhood obesity and short stature in a dose-dependent manner |

| · Dose-response relationship observed; both parents smoking further increased risks | |||||

| Lu et al.[139] (2021) | Systematic review and meta-analysis | Sleep disturbances during pregnancy (poor sleep quality, extreme sleep duration, insomnia, RLS, SDB, OSA) | 58,123,250 pregnant women (120 studies) | · Sleep disturbances associated with higher risk of GDM (OR = 1.59), pre-eclampsia (OR = 2.80), gestational hypertension (OR = 1.74), cesarean section (OR = 1.47), preterm birth (OR = 1.38), LGA (OR = 1.40), and stillbirth (OR = 1.25) | Sleep disturbances during pregnancy are significantly associated with adverse maternal and fetal outcomes, highlighting the need for sleep assessment and management in prenatal care |

| · No significant association with SGA or low birth weight | |||||

| Cajachagua - Torres et al.[125] (2022) | Generation R Study, Netherlands (prospective cohort) | Maternal and paternal tobacco and cannabis use | 4,792 children | · Maternal tobacco use associated with higher android/gynoid fat ratio, fat mass index, and triglycerides at age 10 | Associations may be explained by shared familial and lifestyle factors rather than direct fetal programming |

| · Both maternal and paternal substance use showed similar associations, suggesting familial confounding | |||||

| Wang et al.[134] (2022) | NHSII and GUTS I/II, USA (prospective cohort) | Maternal ultra-processed food consumption during child-rearing period | 19,958 mother-child pairs | · Maternal ultra-processed food consumption during child-rearing period associated with 26% higher risk of offspring overweight/obesity (highest vs. lowest intake group) | Maternal consumption of ultra-processed foods during child-rearing is associated with increased offspring obesity risk, supporting dietary recommendations for women of reproductive age |

| · Association independent of offspring’s ultra-processed food intake, physical activity, and sedentary time | |||||

| Hedderson et al.[133] (2024) | ECHO Consortium, US (multi-cohort prospective study) | Prenatal diet quality (HEI and EDIP) | 2,854 dyads | · High HEI (> 80) associated with lower odds of LGA, rapid growth at 6 and 24 months, and slow growth at 6, 12, 24 months | A healthy prenatal diet per USDA guidelines is associated with healthier infant growth patterns, potentially reducing obesity risk |

| · EDIP associations were inconsistent |

Prenatal tobacco exposure and childhood obesity

Prenatal exposure to tobacco, including both active and passive smoking, is a significant risk factor for increased obesity in offspring. This effect has been supported by multiple large-scale cohort studies and systematic reviews. A study based on the Israeli EHF (Environmental Health Fund) birth cohort[122] - which was validated through biomarkers - found that elevated urinary cotinine levels in pregnant women due to paternal smoking were significantly associated with reduced birth weight in male offspring. A 2025 systematic review incorporating 13 studies explicitly stated that paternal smoking during pregnancy increases the risk of offspring becoming obese[123]. For example, Koshy et al. found that children exposed to maternal smoking during pregnancy had a significantly higher prevalence of being overweight or obese at ages 5-11 compared to unexposed children, with an adjusted OR of 1.61[124]. Furthermore, children of heavy smokers were found to be at an even greater risk. Analysis of nearly 9,500 children from the United States Environmental influences on Child Health Outcomes (ECHO) cohort[125] further confirmed that prenatal tobacco exposure significantly correlates with abnormal BMI trajectories (non-typical rapid ascending patterns), resulting in an average BMI of 26.2 (above the 99th percentile) by age 9. Systematic reviews indicate that maternal smoking increases the risk of offspring being overweight by 50% between the ages of 3 and 33[126], and there is a dose-response relationship between smoking intensity and childhood obesity risk[127]. A study of late adolescents[128] further revealed that prenatal tobacco exposure was associated with significantly elevated levels of subcutaneous fat (26%) and visceral fat (33%). While the absolute weight gain attributable to maternal smoking was modest, its effects were persistent in the long term. This underscores the public health significance of prenatal tobacco exposure as a major preventable risk factor for offspring obesity.

Its mechanisms involve alterations in epigenetic programming and neuroendocrine regulation. Maternal smoking has a substantial impact on chemokine gene expression in neonatal skin tissue, accompanied by a decline in methylation levels at specific cytosine-phosphate-guanine (CpG) sites (e.g., chr7:150038291). This observation suggests that tobacco exposure may enhance chemokine transcription through epigenetic regulation[129]. As a pro-adipogenic and pro-inflammatory adipokine, its abnormally elevated expression during fetal development may promote adipocyte differentiation and lipid accumulation, thereby providing a molecular basis for obesity in later life[129]. As indicated by the findings of animal studies[130] , prenatal exposure to nicotine has been demonstrated to correlate with increased body weight, elevated blood pressure, and impaired glucose metabolism in offspring. Furthermore, the hypothesis that altered hypothalamic regulation of appetite and satiety constitutes an additional critical mechanism is considered. Morphological and functional alterations in these regulatory systems have been observed in offspring exposed to tobacco during gestation[131,132]. Collectively, these mechanisms illustrate how tobacco exposure programs offspring energy metabolism regulation via epigenetic and neuroendocrine pathways, thereby increasing long-term susceptibility to obesity.

Prenatal dietary patterns and childhood obesity

The quality of maternal nutrition during pregnancy exerts a significant influence on offspring birth weight, early growth patterns, and long-term obesity risk. Extensive research indicates that adhering to healthy dietary patterns during pregnancy is associated with more favorable growth trajectories in offspring. In 2024, Hedderson et al. found that higher maternal Healthy Eating Index (HEI-2015) scores (indicating greater adherence to dietary guidelines) were associated with a reduced risk of offspring being large for gestational age (LGA) and with significantly decreased rapid growth from birth to 6 months and 24 months of age[133]. Conversely, a high maternal intake of ultra-processed foods was found to significantly increase the risk of overweight or obesity in offspring. A cohort study of 19,958 mother-child pairs[134] demonstrated that offspring in the highest maternal ultra-processed food intake group exhibited a 26% higher risk ratio compared to the lowest group. Furthermore, Voerman et al. found that high maternal caffeine intake during pregnancy was associated with higher childhood BMI, total fat mass, abdominal visceral fat, and hepatic fat content[135]. The present findings suggest that maternal dietary patterns have a significant influence on the obesity risk of offspring in later life by way of programming early growth.

Its mechanisms involve nutrition-mediated metabolic programming and transgenerational effects. As demonstrated by Saben et al., experimental research on animals has shown that a high-fat/high-sugar diet during pregnancy can result in mitochondrial morphological abnormalities and kinetic dysregulation [e.g., reduced Dynamin-related protein 1 (DRP1) phosphorylation and decreased Optic atrophy 1 (OPA1) expression] in the skeletal muscle of F1 female offspring[136]. This has been shown to lead to impaired insulin signaling and lipid oxidation dysfunction. It is important to note that these mitochondrial phenotypes can be transmitted to F2 and F3 generations via oocyte mitochondria. It has been demonstrated that even when offspring are fed a normal diet, transgenerational mitochondrial dysfunction persists. These effects are partly mediated by epigenetic mechanisms, such as DNA hypomethylation at gene promoters, which can program the central reward circuitry and hypothalamic appetite regulation [involving genes such as POMC, dopamine reuptake transporter (DAT), and µ-opioid receptor (MOR)], thereby influencing offspring’s preference for palatable foods and increasing obesity susceptibility[119,137]. This indicates that maternal nutritional status influences long-term obesity and metabolic risks in offspring through germ cell mitochondrial quality[136]. Another intriguing mechanism involves olfactory programming. Research has demonstrated that exposure of the mother to particular odors during pregnancy activates olfactory sensory neurons that express the relevant receptors in the fetus. This results in significantly enlarged olfactory bulb neurofibrillary spheres and enhanced offspring preference for the odor experienced during pregnancy[138]. This early neuroanatomical programming may promote offspring recognition and attraction to high-energy food odors, thereby programming their long-term feeding behavior and obesity risk.

Prenatal sleep disorders and childhood obesity

Sleep disturbances during pregnancy, including sleep disorders, snoring, and insomnia, have been demonstrated to be significantly associated with adverse birth outcomes and long-term obesity risks in offspring. A substantial meta-analysis[139] encompassing over 58 million pregnant women has demonstrated that maternal insomnia during pregnancy increases the risk of LGA infants. Specifically, pregnancy-related snoring has been shown to be associated with higher risks of macrosomia and LGA in offspring, and this association remains robust after adjusting for pre-pregnancy BMI, suggesting that sleep disturbances may influence fetal growth independently of obesity itself[140-142]. The findings regarding the association between sleep duration and birth weight are inconsistent. A number of studies[143] have indicated that a sleep duration of less than 8 h is associated with an increased risk of SGA. Conversely, other studies[144] have reported that a sleep duration of ≥ 9 h per night during the mid-to-late stages of pregnancy is associated with higher mean birth weight in offspring.

Its mechanisms primarily involve multiple pathways, including metabolic, neuroendocrine, and epigenetic processes. Sleep deprivation or fragmented sleep has been demonstrated to result in maternal glucose metabolism abnormalities, reduced insulin sensitivity, and elevated systemic inflammation (e.g., increased C-reactive protein, IL-6, TNF-α), thereby affecting placental function and fetal energy metabolism programming[145]. Sleep disturbances have been demonstrated to disrupt maternal hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis function, resulting in elevated cortisol levels and, consequently, indirect interference with fetal hypothalamic appetite regulation center development. This results in an alteration of the regulatory balance of leptin and ghrelin, which in turn programs long-term energy homeostasis in offspring[145,146]. Epigenetic mechanisms have also been demonstrated to play a role. The results of animal studies suggest that exposure to fragmented sleep during pregnancy can induce methylation modifications in genes associated with fat metabolism, including adiponectin (AdipoQ; adiponectin, C1Q and collagen domain containing). This, in turn, has been shown to increase the susceptibility of offspring to obesity[145]. The biological basis through which maternal sleep during pregnancy influences offspring obesity is formed by the collective influence of metabolic, neuroendocrine, and epigenetic pathways.

Prenatal physical inactivity and childhood obesity

Lack of physical activity during pregnancy has been identified as a significant modifiable risk factor for offspring obesity in early life. The extant research suggests that levels of physical activity in early pregnancy may be associated with offspring birth weight. This association may be sex-specific. A study based on the Omega pregnancy cohort[120] revealed no overall significant association between leisure-time physical activity (LTPA) of ≥ 150 min/week during early pregnancy and offspring birth weight. However, a stratified analysis suggested gender differences, with a slight increase in birth weight among male offspring, while female offspring showed a decrease[120]. Concurrently, a large cohort study[147] indicated that maternal pre-pregnancy obesity was significantly associated with increased risk of LGA offspring [relative risk (RR) = 1.40], with LGA being a strong predictor of childhood obesity. It is noteworthy that when both parents are obese, the risk of LGA in offspring is further increased to 1.70, suggesting a synergistic effect of parental obesity[147]. Whilst these associations are primarily inferred from body weight status, obesity is often closely linked to sedentary lifestyles. Consequently, the promotion of moderate physical activity during pregnancy as a pivotal weight management strategy may facilitate the enhancement of fetal growth patterns, thereby attenuating the long-term risk of obesity in offspring.

Prenatal psychological pressure and childhood obesity

Prenatal psychological pressure is a significant environmental exposure factor that may be associated with an increased risk of obesity in offspring. While direct evidence remains limited, existing research[120] suggests that maternal psychological stress during pregnancy may disrupt the normal development of fetal energy metabolism pathways indirectly by affecting metabolic homeostasis, inflammatory states, and hormonal balance. Furthermore, maternal stress is often accompanied by lifestyle changes, such as unhealthy dietary behaviors and abnormal weight gain, which may collectively increase offspring susceptibility to obesity later in life. However, large-scale clinical studies in this field remain scarce. Future research should explore the independent impact of maternal mental health during pregnancy on offspring weight regulation and its public health implications.

Interactions among multidimensional prenatal environmental factors

Emerging evidence from large contemporary birth cohorts highlights significant synergistic interactions among prenatal multidimensional exposures that substantially amplify the risk of offspring obesity. In the Greek Rhea cohort (n = 633 mother-child pairs), prenatal PM10 exposure was associated with increased adiposity at age 6 years exclusively among children whose mothers consumed < 5 servings of fruits and vegetables per day: per SD increase in PM10, BMI increased by 0.41 kg/m2 (p-interaction = 0.037), waist circumference by 0.83 cm (p-interaction = 0.043), and fat mass by 0.5 kg (p-interaction = 0.039); no such associations were observed in the high-intake group (≥ 5 servings/day), demonstrating clear effect modification by prenatal dietary antioxidant intake[148]. Similarly, another research[149] demonstrates that prenatal environmental tobacco smoke (ETS) exposure is an independent risk factor for childhood obesity, while a lack of maternal supplementation with multivitamins, folic acid, or iron during pregnancy also independently elevates the risk. Crucially, these two adverse exposures exhibit an additive effect: children with combined exposure to prenatal ETS and no maternal supplementation of these nutrients face the highest risk of obesity (e.g., adjusted OR of 1.55 for ETS + no folic acid), indicating an additive interaction. This suggests that adequate prenatal micronutrient status may partially counteract the adverse metabolic programming effects of tobacco smoke.

Beyond the type of exposure, the strength and nature of these multidimensional interactions are further modulated by the timing of exposure and fetal sex, adding layers of complexity. A study of urban preschoolers[65] identified sex-specific sensitive windows for PM2.5 exposure. Exposure during mid-pregnancy (e.g., 8-17 weeks) was associated with higher BMI z-scores and fat mass in boys but not girls, while exposure during mid-to-late pregnancy (e.g., 10-29 weeks) was associated with an increased waist-to-hip ratio in girls only. This demonstrates that the same pollutant can have divergent effects on body composition depending on the specific gestational period of exposure and the sex of the fetus[65].

In conclusion, the risk of childhood obesity results from the complex interplay of multiple prenatal factors, including environmental pollutants, maternal nutritional status, and the critical timing of exposure modulated by fetal sex. Future research should employ methods capable of capturing these dynamic interactions. Public health strategies must integrate dual pathways: reducing harmful exposures (e.g., tobacco smoke, air pollution) and promoting optimal prenatal nutrition (e.g., supplementation of key nutrients, adequate fruit and vegetable intake).

Translational implications and preventive strategies

Translating mechanistic insights from the DOHaD framework into clinical practice requires evidence-based preventive strategies that exploit developmental plasticity during critical prenatal windows to interrupt the programming of fetal obesity and subsequent childhood adiposity.

Current lifestyle adjustments proven effective in mitigating fetal obesity include integrated prenatal diet and physical activity interventions. For instance, a systematic review and meta-analysis of 117 randomized trials (involving 34,546 women) found that antenatal diet interventions reduced GWG by 2.63 kg (95%CI: -3.87 to -1.40) and the risk of large-for-gestational-age neonates (OR = 0.19, 95%CI: 0.08-0.47), while combined diet and physical activity interventions lowered GWG by 1.35 kg (95%CI: -1.95 to -0.75) and gestational diabetes risk (OR = 0.72, 95%CI: 0.54-0.96) compared to routine care[150]. Notably, optimizing the intrauterine environment to mitigate offspring obesity risk may include digital lifestyle interventions during pregnancy. Such app-supported programs - which promote healthy GWG through structured self-monitoring, personalized feedback, and goal setting - represent a promising modifiable approach. Recent evidence syntheses indicate these interventions can effectively improve maternal weight outcomes, a key modifiable determinant of the intrauterine metabolic milieu, thereby potentially contributing to reduced long-term obesity risk in offspring[151-153]. Beyond lifestyle modifications, psychological interventions such as mindfulness-based approaches show promise in improving maternal mental health and moderating GWG, which may indirectly influence offspring obesity risk, though direct evidence remains limited and further high-quality studies are needed[154,155]. In a randomized controlled trial comparing oral metformin to insulin for gestational diabetes management initiated after diagnosis (typically during the mid-second to third trimester) and continued until delivery, metformin was associated with a lower incidence of neonatal hypoglycemia (17% vs. 35%) and reduced neonatal birth weight (3,101 ± 287 g vs. 3,698 ± 422 g), although the incidence of macrosomia did not differ significantly between groups (12% vs. 11%). Maternal compliance was significantly higher in the metformin group (84% vs. 33%)[156]. Beyond behavioral and clinical strategies, environmental modification offers a direct intervention. A randomized trial in Mongolia[69] found that using portable high efficiency particulate air (HEPA) cleaners throughout pregnancy, starting in the first trimester (median 11.5 weeks’ gestation) and continuing until birth, reduced the child’s BMI z-score at age two (-0.16 units) and the odds of overweight/obesity (OR = 0.59) compared to controls. This aligns with biological pathways where lowering prenatal PM2.5 exposure during this critical developmental window may alleviate fetal oxidative stress and inflammatory dysregulation, thereby modulating metabolic programming.

Multidisciplinary and personalized protocols show promise in modifying obesogenic trajectories by leveraging developmental plasticity, especially when started before or early in pregnancy. However, current evidence remains preliminary. Future research should prioritize rigorous trials to confirm their long-term benefits and safety, which is essential for their future inclusion in preventive guidelines.

CONCLUSION

This review systematically examines how multidimensional environmental exposures during intrauterine development impact the risk of childhood obesity, considering factors such as EDCs, air pollutants, maternal metabolic abnormalities, and adverse lifestyle choices. It explores the mechanisms through which these exposures disrupt fetal energy metabolism programming via shared pathways such as epigenetic regulation, placental dysfunction, and metabolic inflammation. Existing evidence suggests that intrauterine environmental exposures act synergistically to influence offspring obesity susceptibility, highlighting the critical importance of early-life environmental exposure in shaping developmental trajectories. However, current research has several limitations. Most evidence stems from studies examining single exposures or mechanisms, with insufficient analysis of multi-exposure interactions and identification of sensitive windows and the mechanisms underlying sex differences. Furthermore, exposure assessment methods require standardization, particularly with regard to dose-response relationships in real-world mixed exposure scenarios. Future research should integrate exposomics, epigenomics, and multi-omics technologies to construct dynamic, spatiotemporal models of early-life environmental exposures, shifting the paradigm from “single-factor” to “multi-dimensional interaction” studies. At the same time, long-term follow-up and intervention studies in population cohorts must be strengthened in order to elucidate the mechanisms of plasticity during critical periods. This will lay the groundwork for the development of targeted, early risk stratification and precision prevention strategies, with the ultimate goal of achieving source-level prevention and control of childhood obesity.

DECLARATIONS

Acknowledgments

The Graphical Abstract is created using BioRender (https://app.biorender.com/citation/6951ef4a8651c8e95018cf91).

Authors’ contributions

Conceptualization: Li J, Zheng J

Writing - original draft preparation: Zhang B

Writing - review and editing: Zhang B, Gao B

Supervision: Li J, Zheng J

All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Financial support and sponsorship

This work was funded by the Noncommunicable Chronic Diseases-National Science and Technology Major Project (2024ZD0531500, 2024ZD0531506), the National Key R&D Program of China (Grant No. 2023YFC2508303), the Basic Scientific Research Project of the Liaoning Provincial Department of Education (Grant No. LJ212410159030), and the Beijing Medical Award Foundation (Grant No. YXJL-2024-0350-0089) to Li J.

Conflicts of interest

All authors declared that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026.

REFERENCES