Agentic material science

Abstract

Artificial intelligence (AI) agents, leveraging capabilities in natural language understanding, multimodal knowledge fusion, and tool invocation, are driving material science towards a new stage of agent-driven. This article systematically reviews the progress of AI agents in material science. It highlights their core innovation in material knowledge processing, structure design, and property calculation, significantly accelerating the materials design process. Furthermore, the article analyzes the impact of agents on experiments, which promote the automation of material synthesis and characterization. The integration of these capabilities is driving the development of self-driving laboratories, moving the field towards end-to-end autonomous materials creation. By providing a comprehensive overview of this rapidly developing field, this review aims to clarify the deep integration of AI agents with material science, thereby accelerating the realization of on-demand material design.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

Material science, as a pivotal discipline underpinning national strategic demands such as energy transition, biomedicine, and advanced manufacturing, directly determines the progress of key technologies and industrial competitiveness. Its central challenge lies in how to efficiently discover, design, and synthesize novel materials with targeted functionalities. Traditional materials research and development primarily rely on experimental trial-and-error and empirical knowledge. This process is not only time-consuming and resource-intensive, but also often constrained by the limitations of human cognition, making it difficult to meet the urgent demand for high-performance and functionally customized materials. In recent years, the emergence of artificial intelligence (AI) for Material Science, particularly the breakthroughs in large language models (LLMs) and AI fundamental models, has brought unprecedented opportunities to accelerate materials discovery, reshaping the research paradigm of material science with unparalleled depth and breadth[1-4].

The integration of AI with material science has followed a clear evolutionary path. The earliest attempts involved expert systems, which encapsulated human knowledge into strict rules for specific tasks such as phase diagram prediction[5] or identification of organic molecules[6]. While developing, their reliance on manually organizing knowledge limited their scope and adaptability. The rise of machine learning (ML), powered by increasing computational resources and materials data, marked a paradigm shift towards data-driven discovery. ML models are good at discovering hidden patterns in high-dimensional spaces for tasks such as property prediction and virtual screening. However, they are usually designed for specific tasks, resulting in a lack of universality. Recently, breakthroughs in LLMs endowed them with transformative capabilities in natural language understanding and generation, making it possible to interact with vast scientific literature and knowledge bases and leverage the knowledge value they contain. On this basis, AI agents represent a new research paradigm. Central to this transformation is the research paradigm shift from AI for Material Science to Agentic Material Science[7]. In this new paradigm, LLM-based agents are no longer limited to specialized models for performing a single task; instead, they evolve into “virtual researchers” capable of autonomous reasoning, planning, decision-making, and executing complex scientific research workflows[8,9]. AI agents are transforming material science from a data-driven to an agent-driven paradigm.

AI agents, with their powerful capabilities in natural language understanding and reasoning, multimodal knowledge fusion, and professional integration with domain-specific tools, are becoming the critical facilitators integrating the full workflow of materials research and development from concept and theory to computation and experiment[10,11]. They are reshaping every stage of materials discovery. This agent-in-the-loop paradigm ultimately aims to achieve fully autonomous self-driving laboratories (SDLs), enabling end-to-end automation in literature mining, hypothesis generation, experimental design, materials synthesis, and data interpretation. It signifies a rapid evolution of materials research and development toward complete autonomy and intelligence[12].

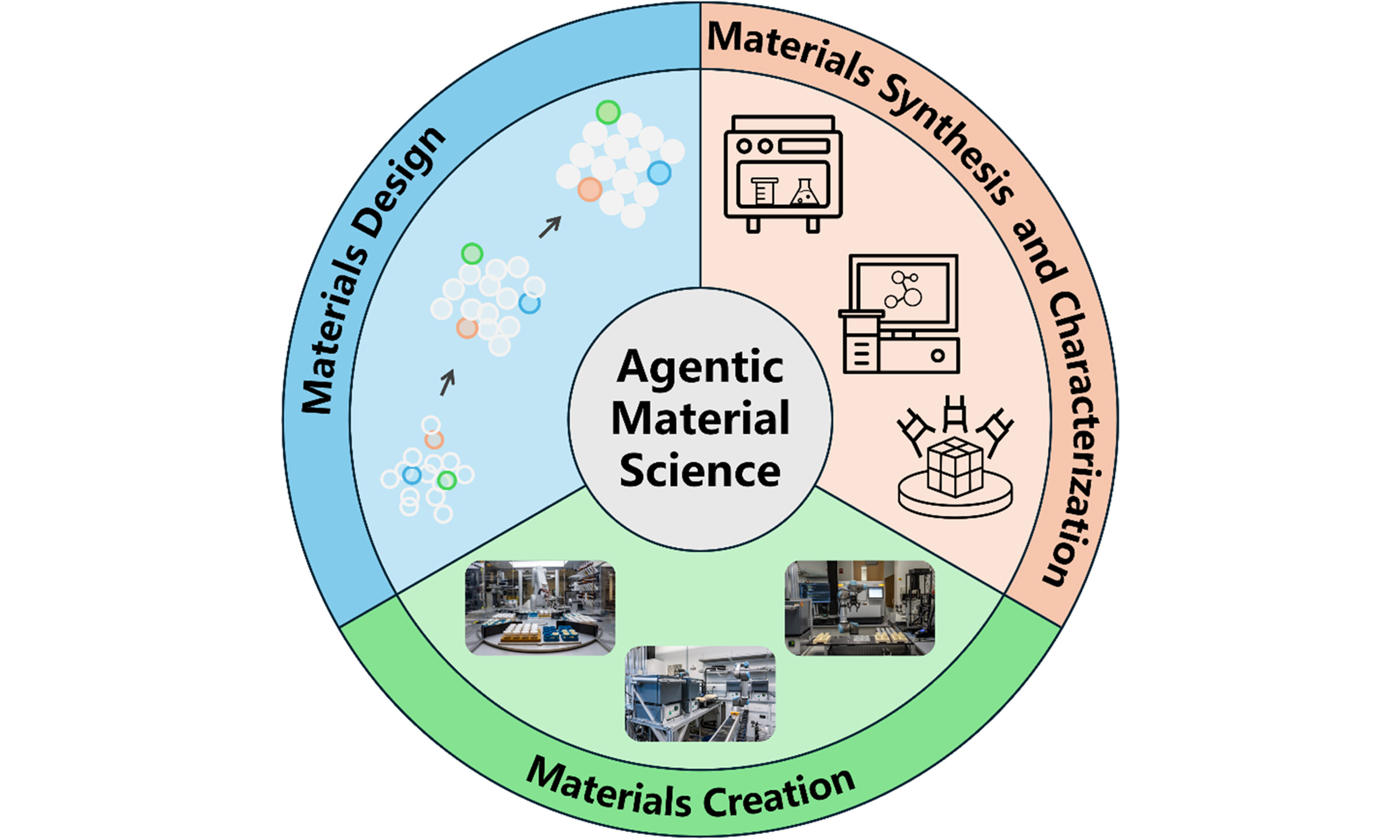

Currently, the application of AI agents in material science is evolving along two distinct yet interconnected pathways: materials design and materials synthesis and characterization[13]. In materials design, agents have demonstrated diverse applications including precisely extracting structured knowledge from large volumes of scientific literature to facilitate knowledge discovery[14], enabling accurate and in-depth material knowledge question answering to promote scientific communication, generating innovative material hypotheses to guide material design, creating and optimizing material structures to explore vast material spaces, and performing complex theoretical calculations to predict material properties[15,16]. These applications form a comprehensive system for materials design, significantly enhancing research efficiency and innovative capacity. In materials synthesis and characterization, the role of agents extends into experimental workflows by enabling the exploration of novel synthesis processes beyond conventional limits, automating material characterization to enhance research efficiency, and analyzing complex experimental data to uncover fundamental relationships. These applications not only improve synthesis efficiency but also reduce experimental costs, making materials research more precise and controllable. More importantly, agents have driven the development of SDLs, which effectively integrate theoretical design in the computational domain with experimental validation in the experimental domain, marking the advent of a new era of automated and intelligent materials research[17,18].

This review aims to systematically analyze the recent progress and development trends in the application of agents in material science. Following the logical flow of materials research and development, the article is structured around three core phases: materials design, materials synthesis and characterization, and autonomous laboratories. The first section focuses on the role of agents in materials design, highlighting their applications in literature data extraction, material knowledge question answering, scientific hypothesis generation, material structure design, and theoretical property calculation. The second section discusses the application of agents across the entire process of materials synthesis and characterization, including material synthesis processes exploration, autonomous material characterization, experimental data analysis, and science theory discovery. The third section presents specific examples of agent-driven SDLs and reviews their developmental process. Through this systematic review, the article aims to provide a comprehensive perspective on AI agent technologies for material science researchers, facilitate the integration of AI and material science, and accelerate the innovation and application of new materials.

AGENTIC MATERIALS DESIGN

Materials design is a process of pursuing innovation and breakthroughs from vast information and complex rules. Its key challenge lies in the efficient identification of materials with target properties from an expansive materials space. In the traditional paradigm, researchers had to manually search literature, analyze data, propose hypotheses, and perform computational verification. This process is not only inefficient but also limited by human cognitive constraints. The introduction of AI agents is fundamentally transforming this paradigm. By deeply integrating the cognitive capabilities of LLMs with the computational power of professional tools, they form an autonomous design system spanning from data extraction to theoretical design. This section will systematically analyze how AI agents empower key stages of materials design and elaborate on the implementation pathways and technological breakthroughs across five critical tasks.

Data extraction

Scientific literature is the largest repository of materials knowledge, and the structured processing of literature data forms the foundation of intelligent applications. However, its unstructured form renders manual extraction inefficient and susceptible to omission of key information or errors. Agents based on LLMs, through their powerful natural language understanding, multimodal processing, and multi-tool coordination capabilities, effectively overcome the challenges of scattered, heterogeneous, and large-scale literature data. They significantly improve the efficiency and accuracy of data extraction, enabling efficient and precise knowledge extraction from scientific literature[19-21].

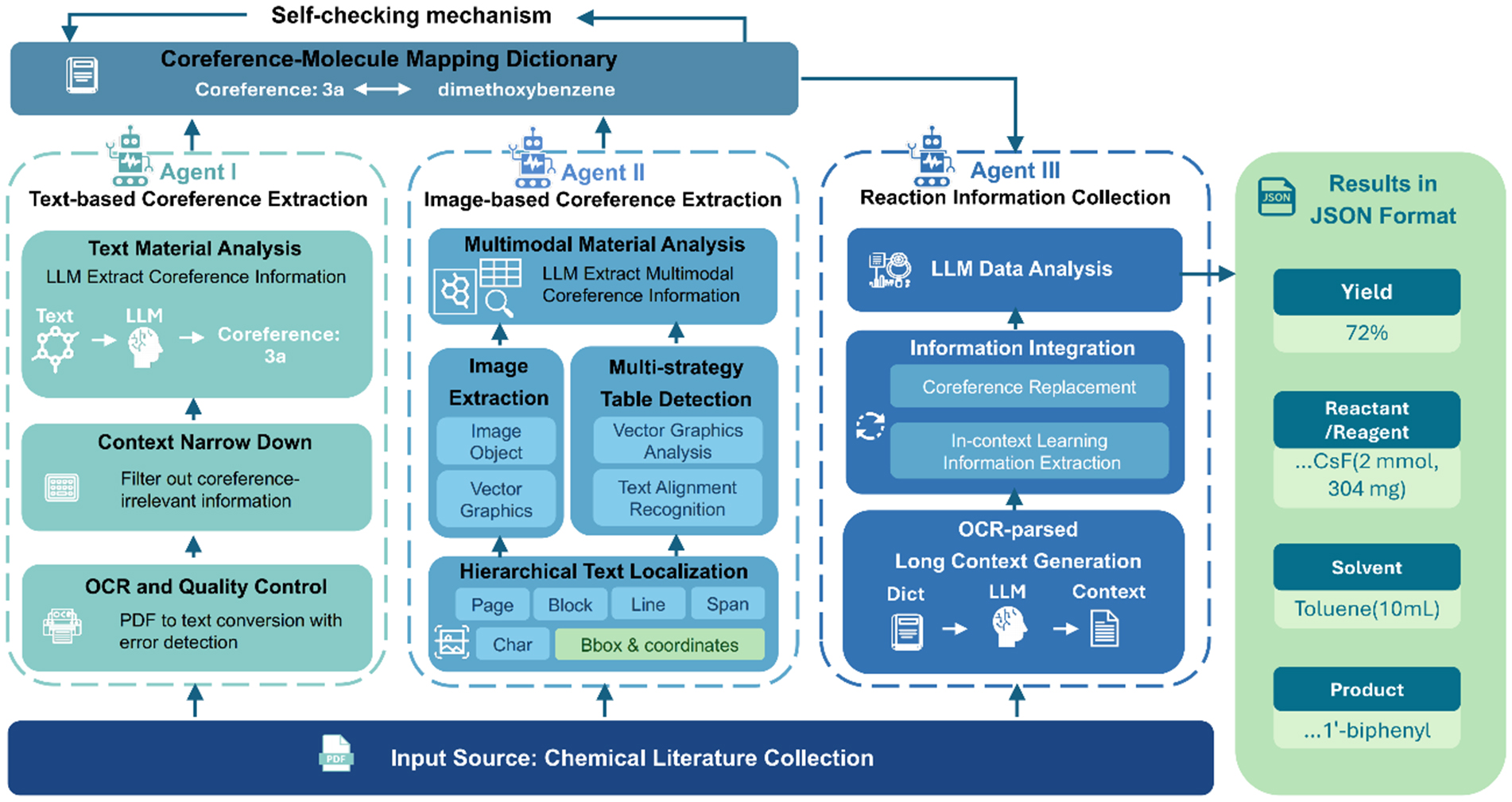

These systems typically employ multi-agent systems (MAS), where role function definition and task decomposition are used to enhance the comprehensiveness and accuracy of data extraction. For example, ChemMiner incorporates three specialized agents for text analysis, multimodal analysis, and synthesis analysis, to process complex coreference mapping relationships, non-textual information, such as figures and tables, and final data generation, respectively. This enables end-to-end extraction of reaction information from chemical literature, achieving performance close to that of human chemists while significantly reducing processing time[22] [Figure 1]. Similarly, nanoMINER uses a ReAct (Reasoning and Acting) agent to coordinate multiple specialized agents, together with visual tools such as You-Only-Look-Once (YOLO) for multimodal analysis. This framework enables highly accurate end-to-end extraction of nanomaterial structural properties (e.g., chemical formulas, crystal systems, and surface characteristics) as well as kinetic parameters of nanozymes[23]. Multicrossmodal LLM-agent coordinates a team of specialized agents to extract and integrate multimodal data from sources such as literature, simulation videos, and microscopy images into a shared embedding space. Through cross-modal fusion and visual information interpretation, it achieves unified reasoning of multimodal data, thereby improving extraction accuracy[24]. Eunomia autonomously plans and executes the creation of structured material datasets in research fields such as solid-state electrolytes (SSEs) and metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) from scientific literature, and extracts design guidelines for materials with specific properties[25]. MechGPT employs a fine-tuned LLM to retrieve and connect cross-scale knowledge from literature, constructs knowledge graphs, and extracts structured insights to provide support for knowledge retrieval and hypothesis generation[26].

Figure 1. Framework of ChemMiner[22]. Data extraction systems typically adopt multi-agent systems, where different functional agents are responsible for specific forms of data extraction to ensure the comprehensiveness and accuracy of data extraction. Reproduced from “ChemMiner: A Large Language Model Agent System For Chemical Literature Data Mining”, arXiv:2402.12993, with permission of the authors[22]. LLM: Large language model; OCR: optical character recognition; JSON: JavaScript Object Notation.

To overcome the limitations of single-modal approaches, the Descriptive Interpretation of Visual Expression (DIVE) multi-agent workflow focuses on extracting experimental data from figures and tables in scientific literature. When parsing data related to solid-state hydrogen storage materials, its MAS significantly improves both extraction accuracy and coverage compared to directly using multimodal models. Based on 4,000 research articles, DIVE successfully constructed a database containing over 30,000 data entries and achieved reverse design of materials within two minutes[27]. In terms of enhancing the reliability and generalization capability of agents, SLM-MATRIX introduces a multi-path collaborative reasoning and verification framework based on small language models (SLMs). Through three pathways, multi-agent collaboration, generator-discriminator mechanism, and cross-validation, it achieves high-precision extraction in material names, numerical values, and physical units, providing an efficient solution for resource-constrained scenarios[28].

These studies collectively demonstrate that MAS, by emulating the role specialization of research teams, significantly enhances the comprehensiveness and accuracy of data extraction and enables a synergistic mining of both the depth and breadth of literature information. By transforming unstructured text into high-quality, structured databases, they provide interrelated foundational data that establishes a cornerstone for materials informatics and lays a solid foundation for data-driven materials discovery.

However, fully transforming this potential into a mature paradigm still faces two key challenges. Firstly, on the technical front, although agents can already process multimodal information such as text, charts, and microscopic images in parallel, achieving unified semantic representation and cross-modal deep reasoning of these heterogeneous data remains a core challenge. Semantic gaps and structural differences exist between different modalities, and current cross-modal fusion mechanisms are still immature. These often lead to information loss or erroneous associations during information alignment and joint reasoning, thereby limiting the completeness and accuracy of overall knowledge extraction. Secondly, at the application closed-loop level, systematic solutions are still lacking for seamlessly integrating the extracted massive structured data into the complete workflow, from material design and performance prediction to experimental validation. Therefore, in the future, it is necessary to further explore cross-modal pre-training, knowledge-enhanced multimodal alignment, and intelligent decision-making systems embedded in the material research and development workflow, so as to truly unlock the hidden knowledge value in scientific literature and promote the transformation of material research from data-rich to knowledge-intelligent.

Knowledge question answering

Based on structured data, there is a growing need to efficiently and accurately integrate knowledge scattered in multi-source databases to provide professional answers to questions in material science. The approach of using general-purpose LLMs alone often encounters problems such as outdated knowledge, limited domain expertise, and insufficient interpretability. AI agents offer a new approach to building powerful materials knowledge question answering systems. By integrating techniques such as retrieval-augmented generation (RAG), tool invocation, and dynamic knowledge base update, agents significantly enhance the ability to acquire and reason with professional knowledge. They can retrieve, reason, and generate precise answers from vast amounts of professional information, thereby ensuring responses that are both timely and scientifically reliable.

Specifically, agents employ RAG to dynamically acquire the latest information from external knowledge bases, effectively compensating for potential obsolescence or insufficiency in the LLM’s internal knowledge. For instance, Mixture-of-Workflows for Self-Corrective Retrieval-Augmented Generation (CRAG-MoW) achieved performance comparable to GPT-4o (“o” for “omni”) in question answering and retrieval of multimodal materials data such as molecules, polymers, chemical reactions, and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectra by adopting a multi-agent workflow and self-correcting RAG strategy, highlighting the advantages of structured retrieval and MAS[29]. Similarly, the Collaborative framework of LLM Agents for Drug Discovery (CLADD) generates high-quality responses without domain fine-tuning by collaborating with multiple agents and dynamically retrieving biomedical knowledge bases to contextualize query molecules[30]. MechGPT combines knowledge graphs with RAG to enhance the reasoning capability and interpretability of agents in question answering in interdisciplinary domains[31]. These studies indicate that multi-agent coordination coupled with RAG can effectively improve the quality of complex materials knowledge question answering. Under this collaborative framework, the key to achieving efficient reasoning and accurate answers across modal and cross-domain data lies in how to coordinate the division of tasks among agents. In practice, hierarchical decision-making and role division mechanisms are often adopted. For instance, the “coordinator agent” is responsible for task parsing and allocation, while “specialist agents” handle information of different modalities, such as text, images, or structured data, independently. These agents leverage RAG to achieve complementary knowledge and cross-validation. This division not only enhances the parallel efficiency of the system in processing complex queries but also improves the accuracy and robustness of answers through the fusion of multi-source information. However, collaboration between multiple agents is not inherently efficient. It needs to rely on well-defined communication protocols and dynamic task scheduling strategies to avoid information redundancy or decision conflicts, thereby fully leveraging the ability to integrate cross-modal and cross-domain data.

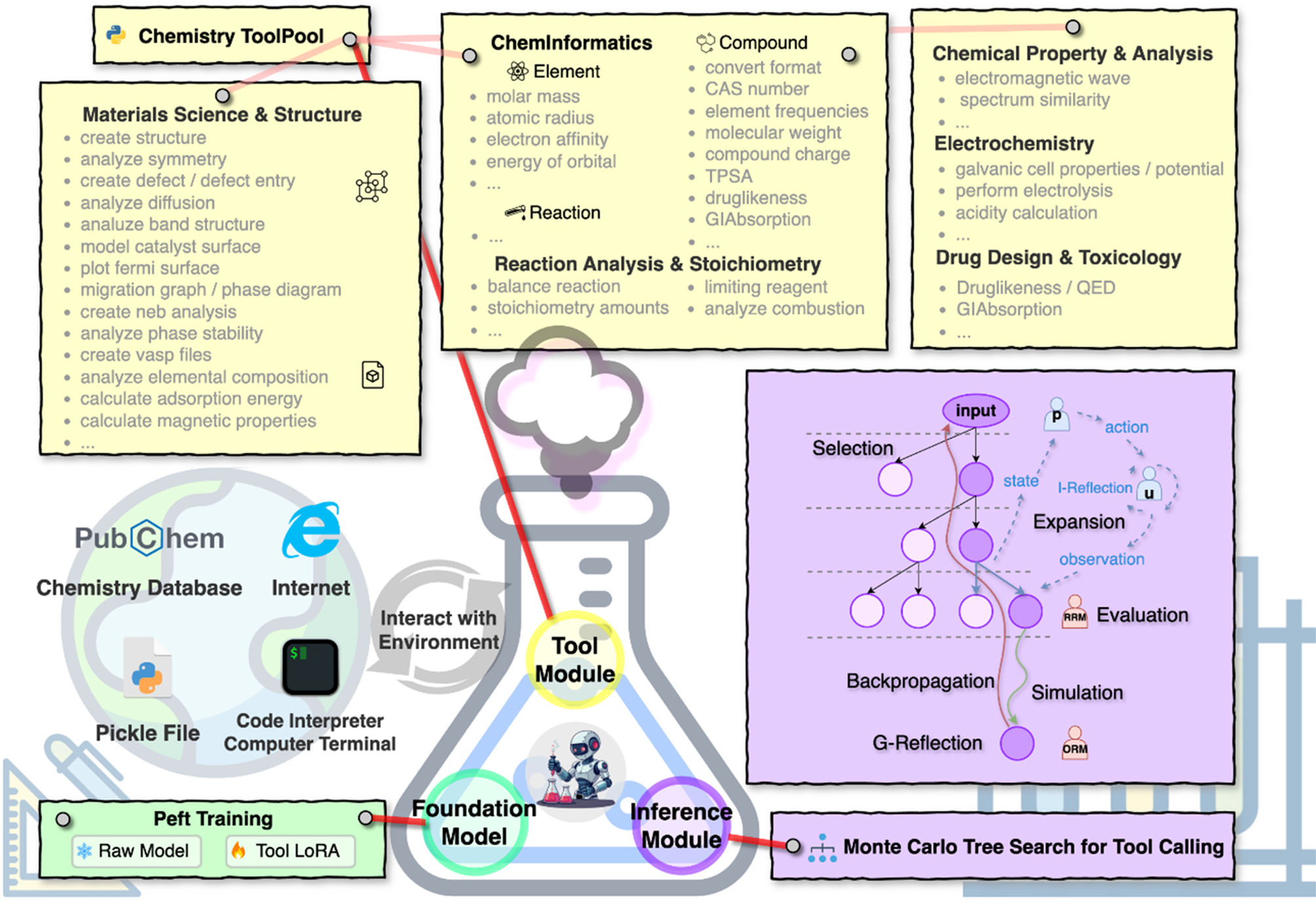

To enhance the professionalism of LLMs and extend their capability boundaries, domain tools have been deeply integrated into AI agents, enabling them to invoke professional tools for precise calculation and validation. For example, Chemistry Agent Connecting Tool Usage to Science (CACTUS), by integrating tools such as RDKit, significantly improves accuracy on question answering benchmarks and enables more reliable molecular property prediction and similarity search[32]. CheMatAgent incorporates 137 chemical tools and the ChemToolBench dataset, and employs a hierarchical evolutionary Monte Carlo Tree Search framework to optimize tool planning and execution, achieving an accuracy in materials question answering that surpasses GPT-4o[33] [Figure 2]. GVIM utilizes an LLM fine-tuned on chemical domain data and integrates professional tools for molecular visualization and literature retrieval, combined with knowledge accumulation and group collaboration mechanisms, to enhance the professionalism and interactivity quality of question answering[34]. These works highlight the importance of tool invocation for tasks requiring precise calculation. However, the use of tools may not consistently yield benefits. Its effectiveness highly depends on the type of task. A comparative study by ChemToolAgent reveals that for highly specialized tasks such as synthesis prediction, equipping agents with dedicated tools can achieve significant improvement. In contrast, for general chemical knowledge questions (e.g., exam questions), the agent’s ability to correctly reason about chemical knowledge is more important. In such cases, tools do not always provide assistance and may even degrade performance due to superfluous integration[35]. Therefore, when invoking specialized tools, it is necessary to carefully define their usage boundaries to prevent negative effects. A feasible principle is on-demand invocation and moderate integration. The system should first identify and classify the intent of the query. If it is a conceptual or fundamental theoretical question, the system should prioritize relying on the enhanced knowledge base and reasoning modules. Specialized tools should only be triggered when dealing with complex calculations, structural validation, or real-time data retrieval. Additionally, a confidence assessment mechanism for tool outputs needs to be established. If significant discrepancies arise between tool results and semantic reasoning, secondary verification or selective adoption should be applied. Through such conditional tool invocation strategies, the system not only can leverage the advantages of specialized tools in precision tasks, but also effectively avoids performance degradation and resource waste caused by over-reliance or improper invocation.

Figure 2. Overview of CheMatAgent for knowledge question answering[33]. Agents can obtain more professional knowledge and generate more accurate answers by using professional tools for information retrieval and prediction. Reproduced from “CheMatAgent: Enhancing LLMs for Chemistry and Materials Science through Tree-Search Based Tool Learning”, arXiv:2506.07551, under CC BY 4.0 license[33]. LLMs: Large language models; CAS: Chemical Abstracts Service; TPSA: topological polar surface area; QED: quantitative estimate of drug-likeness; LoRA: low-rank adaptation; RRM: reasoning reward model; ORM: outcome reward model.

Building upon this progress, the integration of MAS with dynamic knowledge bases and self-evolving knowledge graphs enables the development of more adaptive and continuously learning question answering systems, offering deeper interpretability and long-term sustainability. For instance, ChemAgent constructs a dynamic and self-updating memory library by decomposing chemical tasks into subtasks and storing them as structured memories. This enables the agent to retrieve and refine relevant information when addressing new problems, thereby significantly enhancing its performance in complex chemical reasoning tasks, achieving a performance improvement of up to 46% on the SciBench chemical reasoning dataset[36]. TopoMAS (Topological materials Multi-Agent System) integrates the entire materials discovery workflow, from query and data retrieval to first-principles validation, into a dynamic knowledge graph, achieving continuous knowledge refinement and iteration. This provides support for answering complex questions involving material design and verification[37]. Such approaches transform AI agents from static question answering systems into dynamic systems capable of accumulating and evolving knowledge.

By integrating RAG, tool utilization, and dynamic knowledge graphs, agent-based question answering systems have evolved from simple information retrieval tools into expert systems capable of performing professional computations, providing in-depth explanations, and continuously self-evolving. This marks a crucial shift in the cognitive capabilities of AI agents in the field of materials from knowing to understanding and applying, thereby laying a solid foundation for the intelligence of material design.

Despite these promising advancements, there are still some challenges in developing powerful and reliable AI agents for material knowledge question answering. First of all, the current agent heavily relies on the quality of retrieval. Irrelevant or inaccurate information retrieved from knowledge base may seriously damage the performance of agent, thereby leading to incorrect final answers. Furthermore, the invocation of specialized tools remains an important issue. Because these tools are highly dependent on the type of task, inappropriate or unnecessary use can reduce performance and waste computing resources. Therefore, complex intent recognition and on-demand invocation mechanisms are required. Finally, ensuring the accuracy, consistency, and scalable management of dynamically evolving knowledge graphs remains a major obstacle to creating a truly self-improving system. Automatic updates may lead to errors. Managing a complex and constantly growing knowledge structure is also challenging. Addressing these challenges is crucial for building a reliable expert system in material science.

Hypothesis generation

The core of materials design lies in proposing novel and reasonable hypotheses. The reasoning capabilities demonstrated by AI agents in knowledge question answering can evolve into creative thinking, enabling them to transform fragmented knowledge into verifiable material hypotheses and shifting materials design from “trial-and-error” to “targeted creation”[38,39]. Research strategies for hypothesis generation by agents can be broadly divided into two categories. One focuses on augmenting the agent’s abilities by integrating external tools and knowledge sources, while the other emphasizes optimizing the internal collaboration mechanisms and reasoning strategies to enhance the quality and innovativeness of generated hypotheses. These approaches jointly advance the automation and rationalization of the materials design process.

In terms of knowledge integration and tool utilization, agents make up for inherent limitations by using external tools and structured knowledge, thereby overcoming the constraints of a single model. For instance, dZiner combines first-principles calculations with physics-inspired models to iteratively optimize material designs, achieving the rational design of MOFs from target properties to structures[40] [Figure 3A]. SciAgents integrates large-scale knowledge graphs with data retrieval tools to explore interdisciplinary connections in the field of biomimetic materials, autonomously generating and optimizing material design hypotheses[41]. ResearchAgent employs a reviewer agent to iteratively define new problems, propose methodologies, and design experiments[42]. SciAgent enhances the LLM with tools specifically built for scientific reasoning tasks, enabling it to retrieve, understand, and apply tools to solve scientific problems[43]. Dolphin establishes a closed-loop research framework in which agents generate new ideas based on experimental feedback and relevant literature, then autonomously implement experiments, debug code, and analyze results, enabling continuous optimization of the research process[44]. The plant-inspired materials design framework integrates BioinspiredLLM, a large language model for the mechanics of biological and bio-inspired materials, together with RAG tools and hierarchical sampling strategies. This approach enables effective extraction of structure-property relationships from plant science literature and guides the experimental preparation of novel pollen-based adhesives[45]. These approaches essentially augment agents with toolchains and knowledge bases, equipping them to function as super-experts.

Figure 3. Research strategies for hypothesis generation by agents. (A) dZiner workflow overview[40]; (B) The MOOSE-Chem framework[47]. Figure 3A is reproduced from “dZiner: Rational Inverse Design of Materials with AI Agents”, arXiv:2410.03963, under CC BY-SA 4.0 license[40]. Figure 3B is reproduced from “MOOSE-Chem: Large Language Models for Rediscovering Unseen Chemistry Scientific Hypotheses”, arXiv:2410.07076, under CC BY 4.0 license[47]. SMILES: Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System; ACS: American Chemical Society; AI: artificial intelligence.

In addition to empowering agents through the integration of external resources, another research focuses on enhancing the intrinsic reasoning and discovery capabilities of agent systems by innovating in multi-agent collaboration frameworks or reasoning-iteration optimization strategies, thereby further improving the quality of generated hypotheses. This type of work emphasizes either interaction among multiple agents or the self-improvement of individual agents to achieve more rigorous and creative scientific reasoning. For example, ReConcile adopts a round-table discussion framework, where multi-round debates and confidence-weighted voting mechanism help reach a consensus, significantly improving reasoning quality[46]. MOOSE-Chem employs a mathematical decomposition framework to break down hypothesis generation into three subtasks: inspiration retrieval, hypothesis combination, and ranking, successfully reproducing high-level chemical and materials hypotheses recently proposed by human scientists[47] [Figure 3B]. MOOSE-Chem2 further formalizes fine-grained hypothesis discovery as a combinatorial optimization problem. Through a hierarchical search method, it gradually refines details from general concepts to specific experimental configurations, and discovers the optimal detailed hypothesis that can be immediately put into experiment by smoothing the internal reward landscape[48]. To more reasonably evaluate hypotheses, MOOSE-Chem3 develops an experimental simulation feedback tool. By introducing a hypothesis ranking task guided by simulated outcomes, candidate schemes were prioritized through clustering and simulation results[49]. AgentRxiv establishes a shared platform for agents that simulates the real-world scientific community, enabling agents to iteratively advance their research based on each other’s research achievements[50]. PiFlow models scientific discovery from an information-theoretic perspective as a structured uncertainty reduction process under the constraints of scientific principles, achieving hypothesis generation with controllable uncertainty in fields such as nanomaterials and superconductors[51]. PriM (a principles-guided materials discovery system powered by a language-inferential MAS) constructs a round-table-style MAS to guide the materials design process in accordance with scientific principles. This approach ensures systematic exploration and transparent reasoning, enabling highly interpretable hypothesis generation in nanomaterials design[52]. Self-Refine demonstrates that even without changing model parameters, self-feedback and iteration of a single agent can significantly improve output quality, enhancing the completeness and accuracy of materials design hypotheses[53]. Virtual Scientists (VIRSCI) simulates research team collaboration through multi-agent division of labor to generate highly novel materials research concepts[54]. Sparks employs paired design and reflection agents for self-correction, discovering new design principles in protein science[55]. DrugAgent automates ML programming in drug material development through collaboration between Planner and Instructor agents[56].

The development of AI agents in materials hypothesis generation and design reflects functional enhancement from expanding external capabilities to optimizing intrinsic reasoning mechanisms. This progress indicates that agents are no longer merely engaged in simple data association, but begin to systematically integrate multi-source knowledge, simulate human scientific inspiration and reasoning processes, and thereby generate more reasonable and verifiable material hypotheses. By efficiently integrating and associating originally fragmented knowledge units, agents not only improve the accuracy of hypothesis generation but also significantly enhance the potential for successful application. However, it should also be recognized that at present, the success rate, innovativeness and feasibility of generated hypotheses still require extensive experimentation and algorithmic optimization for validation and consolidation. Therefore, it is necessary to establish more refined evaluation frameworks for hypothesis quality and develop algorithms capable of quantifying the success rate of hypotheses. Such advancements will not only enhance the creativity of agents but also ensure that the scientific hypotheses have high verifiability and transformation value, thereby driving materials design into an efficient and reliable intelligent era.

Structure design

Transforming qualitative material hypotheses into quantitative material structures is a critical leap in the material design process. By integrating proprietary generative models and data-driven computational tools into LLM-based workflows, AI agents enable automated and intelligent closed-loop exploration of material structure generation. According to the technical approaches adopted for the generation module, existing agent-driven material structure generation methods can be broadly categorized into two types.

The first category involves agents that employ specialized generative models for structure design, while LLMs oversee regulation and control. The core of this approach lies in leveraging models such as diffusion models, generative adversarial networks (GANs), or reinforcement learning (RL) to efficiently explore vast chemical and structural spaces, with LLMs coordinating workflows, evaluating generated outputs, suggesting optimization directions, and orchestrating multi-step processes. For instance, in MOF design, the MOFGen employs an LLM agent to propose new compositions, a diffusion model to generate crystal structures, and combines quantum mechanics tools with a synthesis feasibility assessment agent for screening and optimization. This approach has generated hundreds of thousands of novel MOF structures and successfully synthesized five MOF materials, validating the effectiveness of the agent[57]. CrossMatAgent integrates generative models such as DALL-E 3 and Stable Diffusion XL to create metamaterial structural patterns, with a GPT-4o-driven multimodal agent responsible for performance analysis and supervisory feedback, thereby automating the generation of metamaterial structures[58]. LIDDIA (Language-based Intelligent Drug Discovery Agent) employs molecular generation models guided by LLM reasoning to steer the molecular generation process. By balancing chemical space exploration with optimal molecular utilization, it successfully generates molecules that meet key metrics[59]. Specialized generative models based on RL have been applied in the ACEGEN framework, a comprehensive and streamlined toolkit for generative drug design[60], and in CSstep, a drug molecule generation and optimization framework based on Markov decision processes and reinforcement learning[61]. By applying modular design and multi-agent decision-making strategies, the molecular generation process can be progressively optimized and rendered more interpretable. In the design of two-dimensional (2D) material structures, an RL agent can efficiently generate the MoS₂ structures with enhanced tensile strength after being trained with a small amount of data[62]. ChatMOF utilizes LLM to process natural language inputs and combines databases and ML tools to achieve MOF prediction and generation[63]. MatAgent is a generative framework for inorganic materials discovery that leverages the reasoning capabilities of large language models. In inorganic materials design, it improves the effectiveness, uniqueness, and novelty of candidate materials through iterative feedback between generation and property prediction models[64] [Figure 4A]. The ProtAgents platform deploys multiple function-specific agents responsible for knowledge retrieval, structural analysis, physical simulation, and result analysis to design proteins with target performance[65].

Figure 4. The method of generating material structures by agents. (A) The overview of the MatAgent framework[64]; (B) Pipeline for training and generation using the MolGPT model[66]. Figure 4A is reproduced from “Accelerated Inorganic Materials Design with Generative AI Agents”, arXiv:2504.00741, under CC BY 4.0 license[64]. Figure 4B is reproduced from “MolGPT: Molecular Generation Using a Transformer-Decoder Model”, J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2022, 62, 9, 2064-2076, with permission from American Chemical Society[66]. LLM: Large language model; GNN: graph neural network; RDKiT: RDKit toolkit; LogP: the logarithm of the partition coefficient; TPSA: topological polar surface area; SAS: synthetic accessibility score; QED: quantitative estimate of drug-likeness; MolGPT: molecule generative pre-trained transformer.

As the generative capabilities of LLMs have improved, new approaches have emerged that position LLMs as the core engine for material structure generation, supplemented by specialized tools for verification and optimization. These methods directly leverage the generative capabilities of LLMs by treating material structures, such as SMILES (Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System) strings or text representations of Crystallographic Information File (CIF), as a specialized language. For example, MolGPT (Molecular Generation Using a Transformer-Decoder Model), inspired by text-generation models, uses a Transformer-decoder architecture to train on and generate molecular SMILES sequences[66] [Figure 4B]. Further research indicates that pretrained LLMs without fine-tuning on materials data inherently possess the ability to generate stable crystal structures. For instance, MatLLMSearch combines a pretrained LLM with evolutionary search to achieve high success rates in crystal structure generation and performance optimization[67].

More advanced systems have developed complex MAS centered around LLMs. MT-Mol introduces a multi-agent framework where an LLM-driven scientist agent generates molecules, while multiple analyzer agents invoke RDKit tools for evaluation and feedback, achieving advanced levels in multiple molecular optimization tasks[68]. Organic Structure Directing Agent (OSDA) employs an LLM to generate candidate structures, which are then evaluated by computational tools. Subsequently, the self-reflector summarizes and provides feedback to guide the LLM in optimizing subsequent outputs[69]. The MAPPS (Materials Agent unifying Planning, Physics, and Scientists) framework further conducts workflow planning through LLM, achieving enhanced stability and novelty in material design through integrating generation, physical force field models, and scientist feedback[70].

In summary, AI agents for material structure design are rapidly evolving, demonstrating diverse technical pathways. These systems have achieved notable results, generating hundreds of thousands of novel structures ranging from MOFs and molecules to metamaterials, some of which have been successfully synthesized and validated. The implementation of these systems mainly relies on the collaboration among different components: specialized generative models (diffusion, GANs, RL, and LLMs) provide efficient exploration of the vast material space; physics-based simulation tools ensure credibility and guide the search toward reasonable structures; and LLMs act as the cognitive core, coordinating the entire workflow, facilitating complex reasoning and multi-agent collaboration. This process follows the flow of “generation-evaluation-optimization”, forming a closed loop and improving the design based on feedback. The progress marks a paradigm shift from traditional targeted high-throughput screening toward intelligent creation in materials design.

However, this field still faces numerous challenges at present. Firstly, the alignment between generation intention and physical feasibility is insufficient, with some generated structures potentially violating thermodynamic stability, synthetic feasibility, or chemical constraints of specific systems. Secondly, the scarcity and bias of the training data limit the generalization and transferability of generation models among different material systems. Existing systems fall short in modeling complex material systems with multi-scale and multi-physical field coupling. Looking ahead, agent-driven material structure generation should place greater emphasis on the deep integration of physical prior knowledge. By embedding physical knowledge within the models, the generation of physical knowledge enhancement is achieved to improve the rationality and innovation of the generated structure.

Property calculation

Materials property calculation is the cornerstone for validating the feasibility of materials design and deeply understanding its performance. Although traditional computational methods, from ab initio calculations to molecular dynamics and finite element analysis, have long been the foundation of theoretical insights, they typically have high barriers to entry, require significant computational resources, and involve manual, time-consuming workflows. AI agents demonstrate broad application potential in the field by addressing these limitations. They can use material computational tools and trained ML models to achieve precise and rapid calculations of material properties. This establishes a new paradigm that systematically enhances the efficiency, accessibility, and scale of computational materials science.

A primary advancement of AI agents lies in democratizing complex computational tools. By natural language interaction and modular collaboration, AI agents have been applied to material computational tool empowerment and workflow automation. They can construct and automatically execute theoretical materials property calculation workflows, significantly lowering the barrier to using professional material computational tools. This allows researchers to rapidly invoke complex simulation processes via natural language instructions, achieving efficient operation from setup to execution in materials property calculations. These tasks traditionally require deep expertise in software-specific syntax and theoretical models. For instance, MatSciAgent establishes a multi-agent framework where a primary agent parses natural language user queries and distributes tasks, such as materials data retrieval, crystal structure generation, continuum simulations, and molecular dynamics calculations, to specialized agents. These agents leverage databases such as the Materials Project and customized code to complete the computations[71]. Similarly, platforms such as Aitomia (an AI-powered platform for atomistic and quantum chemical simulations)[72], ChemGraph (an agentic framework for computational chemistry workflows)[73], El Agente (an autonomous agent for quantum chemistry)[74], MatAgent (an intelligent agent specifically designed for predicting material properties)[75], and AutoSolvateWeb (a chatbot-assisted computational platform for quantum chemistry studies)[76] use chatbot interfaces and AI agents to decompose complex tasks into subtasks. This approach simplifies the setup of complex simulations, including excited-state calculations, thermochemical analysis, and quantum mechanics [Figure 5A]. These platforms also proactively guide users through the setup, execution, and analysis of atomic-scale simulations, effectively integrating diverse methods such as first-principles calculations, molecular dynamics, and ML-based potential functions, thereby facilitating the broader adoption of atomic simulation technologies. To address the need for complex input files and execution codes in computational tools, MechAgents[77] enable autonomous coding, correction, and execution of finite element analysis scripts through the collaboration of planning, coding, and execution agents, solving elastic mechanics problems under different boundary conditions. The language-to-simulation (Lang2Sim) framework[78] achieves accurate conversion from text descriptions to executable code for computational tools by decomposing simulation engines into tool functions and input-output pairs. Molecular Dynamics Agent (MDAgent)[79] automatically generates and optimizes LAMMPS (Large-scale Atomic/Molecular Massively Parallel Simulator) molecular dynamics simulation code by fine-tuning LLMs, reducing the average task time by approximately 42.22%. This stands in sharp contrast to the traditional manual preparation of input files and script writing. Such research, by building “natural language-computational tools” interfaces and decomposing tasks, makes core computational tools such as density functional theory (DFT) and molecular dynamics more accessible and executable for materials property calculation. These efforts advance the development of “language-driven simulation” and significantly improve computational efficiency and accessibility.

Figure 5. Agents use material computational tools and ML models to calculate the properties of materials. (A) Computational methods that Aitomia can use and the computing tasks it can perform[72]; (B) GNN model for predicting Peierls barrier and potential energy change[83]. Figure 5A is reproduced from “Aitomia: Your Intelligent Assistant for AI-Driven Atomistic and Quantum Chemical Simulations”, arXiv:2505.08195, under CC BY 4.0 license[72]. Figure 5B is reproduced from “Rapid and Automated Alloy Design with Graph Neural Network-Powered LLM-Driven Multi-Agent Systems”, by Alireza Ghafarollahi and Markus J. Buehler, arXiv:2410.13768, under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 license and the image has not been modified[83]. ML: Machine learning; GNN: graph neural networks; AI: artificial intelligence; LLM: large language model; QM: quantum mechanics; DFT: density functional theory; ANI-1ccx-gelu: a universal interatomic potential for calculating IR anharmonic frequencies; OMNI-P2x: a universal neural network potential for excited-state simulations; MACE-OFF: a series of short-range transferable force fields for organic molecules; AIMent-2: the 2nd generation of atoms-in-molecules neural network potential; AIQM: AI-enhanced quantum mechanics methods; DENS24: density functional ensembles.

Beyond automating traditional tools, by using ML models to calculate material properties, AI agents can rapidly conduct high-throughput screening and multi-objective optimization in the materials space, breaking through the efficiency limitations of traditional screening based on computational tools and achieving intelligent search and design in the material space. For instance, agents adopting an exploration-utilization strategy combined with ML models autonomously conduct stability screening in binary/ternary compound spaces, successfully discovering hundreds of novel stable materials[80,81]. This is impractical through sequential DFT calculations. QMLMaterial (a quantum machine learning software for material design and discovery) efficiently identifies globally optimal structures of atomic clusters, surface adsorption systems, and related materials using active learning algorithms and performance-evaluation ML models[82]. For specific material systems, MAS demonstrates highly efficient screening capabilities. In the field of alloys, LLM-driven MAS collaborates with graph neural networks (GNN) to autonomously explore the design space of NbMoTa alloys and predict macroscopic mechanical strength, accelerating the discovery of advanced alloys[83] [Figure 5B]. In zeolite, after the LLM agent proposes a candidate structure, atomic simulation evaluations provide iterative feedback, efficiently generating novel molecules that exhibit higher binding affinity[84]. In metamaterials, agents automatically generate performance prediction models based on datasets and model architectures, and combine developed generative models to achieve automated inverse design of metamaterials[85]. Moreover, ChemReasoner combines LLM-generated catalyst hypotheses with atomic structure evaluation of GNNs, using metrics such as adsorption energy to guide the search direction, thereby improving the efficiency of catalyst design[86]. SciToolAgent drives hundreds of scientific tools through knowledge graphs and demonstrates powerful automation capabilities in MOF screening scenarios[87,88]. MDLab enables efficient screening for carbon capture and battery materials using ML[89]. The Digital Catalysis Platform (DigCat) establishes a cloud-based global closed-loop feedback system, automating the entire workflow from catalyst design to micro-dynamics simulation and achieving highly efficient catalyst screening[90]. This “prediction-evaluation-feedback” closed-loop paradigm surpasses the traditional slow screening method based on theoretical computation, making AI agents the core driving force for high-throughput material screening and design.

With the in-depth application of AI agents in material property calculation, computational simulations have been used to address the hallucination and credibility issues of LLMs in the materials domain. Here, computational simulations serve as a rigorous, physics-based validator, a function absent in traditional workflows. By incorporating computational verification and feedback, the reliability and scientific rationality of LLMs are enhanced. For example, LLaMP employs RAG and a hierarchical ReAct agent to dynamically query databases such as Materials Project and first-principles calculation tools, correcting LLM prediction deviations for properties such as bulk modulus and bandgap, thereby significantly reducing hallucinations in material property predictions[91]. PolySea, a specialized large model for polymers, needs to undergo triple verification through the polymer genome database, GNN model, and DFT calculation after generating new structures to ensure the credibility of the design results[92]. AtomAgents integrates multimodal data and physical simulations through dynamic multi-agent collaboration, embedding physical principles of alloys into the design process, which improves both the accuracy of performance predictions and the interpretability of alloy design[93]. ChemHAS (Chemical Hierarchical Agent Stacking) enhances the robustness of chemical property prediction by using the agent-stacked structure to compensate for the prediction errors of chemical tools with data[94]. HoneyComb combines a high-quality materials science knowledge base with an adaptive tool selection module, significantly improving accuracy in domain tasks by matching and using the most relevant knowledge and computational tools[95]. xChemAgents employs a dual-agent collaboration mechanism with Selector and Validator. The former adaptively screens chemical descriptors relevant to target properties and provides natural language explanations, while the latter iteratively introduces physical constraints into the descriptors, reducing the mean absolute error of multimodal property predictions by 22%[96]. This integration enables AI-generated hypotheses to be validated against physical laws, creating a self-correcting and trustworthy design loop, laying an important foundation for establishing scientifically rigorous, domain-specific LLMs.

The application of AI agents in materials property calculation plays a dual role of empowerment and feedback. It simplifies and automates complex computational simulations, thereby enhancing research efficiency; meanwhile, the results from these simulations serve as verification feedback, improving the scientific rigor and credibility of the agents’ outputs. This establishes a solid and reliable theoretical foundation for the eventual verification, accelerating the entire journey from conceptual design to experimental realization. There are also some challenges in the widespread adoption and further development of AI agents for materials property calculation. A major issue is the accuracy and generalization of data-driven ML models, which highly depend on the quality, quantity, and diversity of training data. Furthermore, the multiscale characteristic of materials brings significant modeling challenges, as seamlessly integrating simulations from the quantum scale to the macroscopic scale within an agent framework remains an issue. The high computational cost of high-precision simulations, such as DFT, also limits the scale and speed of agent-driven closed-loop exploration.

In summary, AI agents have demonstrated powerful comprehensive capabilities in the materials design stage from literature data mining, knowledge question answering, and hypothesis generation, to specific materials structure design and property calculation. They have achieved a closed-loop, autonomous materials design from knowledge input to theoretical validation.

AGENTIC MATERIALS SYNTHESIS AND CHARACTERIZATION

Materials synthesis and characterization are the key steps in transforming theoretical designs into physical substances. By integrating robot control and experimental equipment, AI agents are being deeply integrated into material synthesis and characterization, enabling the automation and intellectualization of autonomous material synthesis and characterization workflows, thereby significantly enhancing experimental efficiency and exploratory capabilities. For instance, in the development of high-entropy alloy catalysts, agents utilizing Joule heating technology achieve high-throughput synthesis and performance screening. This demonstrates the powerful ability of agents to accelerate material discovery using experimental equipment[97]. In additive manufacturing, AutoMEX (a framework integrating LLMs as AI agents to automate the material extrusion process) autonomously completes the entire workflow, including CAD model generation, slice code creation, and 3D printing operations. This demonstrates its advantage in end-to-end automation of material manufacturing processes[98]. In the field of carbon nanotube synthesis, Carbon Copilot (CARCO) employed chemical vapor deposition (CVD) experimental equipment to discover a Ti-Pt bimetallic catalyst within 43 days, achieving a synthesis precision of 56.25% for horizontally aligned carbon nanotube arrays[99]. Materials synthesis and characterization is a complex process full of uncertainties, involving intricate step planning, process exploration, and data analysis. This section will explore how AI agents can be applied to various aspects of process exploration, material characterization, and data analysis, analyzing their roles in key tasks in material synthesis and characterization.

Synthesis process exploration

The first step in the automated material synthesis is to explore the material synthesis process. In this domain, AI agents demonstrate multi-dimensional and adaptive optimization capabilities. By integrating prior knowledge from knowledge graphs, autonomous exploration via RL, and multi-objective optimization algorithms, they can efficiently balance multiple constraints such as performance, cost, and safety, to achieve full autonomy in reaction route exploration, process parameter search, and multi-objective trade-offs. This significantly enhances the efficiency of synthesis process design and parameter optimization for various materials, effectively breaking through the bottlenecks of traditional process exploration that relies on empirical trial-and-error, struggles with coupled parameters, and faces challenges in traversing complex pathways.

Specifically, by integrating LLMs, knowledge graphs, and RL, agents achieve fully autonomous exploration from reaction route recommendation and process parameter search to multi-objective trade-offs. For example, the agent system based on LLM and knowledge graph automatically extracts reaction data from literature, constructs retrosynthetic pathway trees, and combines multi-branch reaction path search algorithms to recommend new synthesis processes for materials such as polyimides, overcoming the limitations of traditional methods in designing reaction routes for complex macromolecules[100]. Furthermore, for quantum material synthesis, an offline RL agent, trained through tens of thousands of simulations, successfully predicts process parameters for synthesizing MoS2 single crystals via CVD, demonstrating the predictive capability of agents in complex processes such as high-temperature and multi-phase systems[101].

Material processes often require balancing multiple conflicting objectives such as performance, cost, and safety, while satisfying engineering constraints. AI agents can address this challenge through advanced algorithms to enable efficient decision-making. In the exploration space of process parameters, RL agent can achieve the optimization of process parameters guided by target properties through interaction with the environment[102,103]. To address the challenge of multi-objective cooperative optimization, a Bayesian optimization algorithm agent efficiently explores the Pareto frontier among multiple objectives, such as optical properties and reaction rates, in silver nanoparticle synthesis, significantly enhancing the feasibility of synthesis processes under highly constrained conditions[104].

A key advancement lies in the integration of embodied intelligence, where AI agents bridge computational decision-making and physical execution. By integrating real-time detection and perceptual feedback into the experimental process, agents achieve closed-loop optimization. For example, the CLAIRify (LLM-based natural language processing module) system employs constraint-aware motion planning to translate user experimental descriptions into safely executable robot experimental actions. Through real-time sensor detection and feedback, it successfully performs high degrees of freedom operations such as solubility measurement and recrystallization in material synthesis[105]. Similarly, K-Agents uses LLM-based planning to model multi-step experimental operations as robot actions, and calibrates them in real-time using knowledge of laboratory operations and sensor detection feedback[106]. The integration of digital twin technology further enhances this paradigm by providing virtual models of physical systems. These simulate robot trajectories, predict collisions, and optimize task sequences before physical execution. Digital twins also support real-time monitoring and adaptive reconfiguration, improving efficiency and resilience. For instance, as a fundamental support platform, LabUtopia provides a high-fidelity simulation environment for deploying AI agents in physics laboratory settings. It integrates the Simulation Lab (LabSim) simulator, which models high-precision physicochemical interactions, LabScene for generating diverse scientific scenarios, and the LabBench benchmark, covering tasks ranging from atomic actions to long-term operations. By offering a simulation environment that supports multiple physicochemical interactions, including over 200 scenarios and instrumental assets, LabUtopia enables large-scale training and evaluation for 30 categories of complex experimental tasks. It thus serves as a standardized platform for training and comprehensively assessing the perception, planning, and control capabilities of scientific embodied agents in complex laboratory settings, laying a solid foundation for developing embodied AI agents capable of long-term planning and sophisticated operations in real laboratories[107]. In dangerous or fully autonomous environments, safety protocols, including safety barriers, collision detection sensors, and fail-safe mechanisms, are indispensable. By combining motion planning, digital twin simulations, and robust safety systems, robot platforms enhance laboratory efficiency while ensuring safe and effective operations[108].

At the system level, by introducing multi-robot scheduling, hierarchical control, and modular planning, agents can achieve system-level resource optimization in experimental design, significantly improving experimental efficiency. A multi-robot and multi-task scheduling system employing constraint programming methods optimizes task allocation among 3 robots and 18 experimental stations while supporting dynamic task insertion. This reduces the total execution time of complex experiments by nearly 40%, enhancing the parallelism of high-throughput experimentation[109].

These advances indicate that AI agents are transforming synthesis process exploration from trial-and-error into a data-driven science. They establish a new paradigm for process exploration that encompasses path design, parameter search, and multi-objective optimization, providing the core support for the transformation of materials synthesis processes from experience to precise design. In addition, this direction also faces several challenges. Firstly, due to the difficulty in accurately simulating the physicochemical effects under highly complex or extreme conditions, the gap between simulations and real physicochemical processes is still significant. This may influence the generalization ability of the agent trained in a simulation environment when applied to real-world laboratory settings. Furthermore, the stability, safety, and interpretability of system during long-term autonomous operation in laboratories require further enhancement to build more reliable, transparent, and continuously upgradable material agents. These challenges highlight the direction for research on the next generation of AI agents for material synthesis.

Materials characterization

The properties of synthesized materials need to be confirmed through characterization. Experimental characterization is the core means to determine whether the synthesized product meets expectations. Through techniques such as X-ray diffraction (XRD), scanning electron microscopy (SEM), and transmission electron microscopy (TEM), information on the material’s crystal structure, microstructure, and composition distribution is obtained, thereby validating the rationality of process parameters. By integrating ML models, experimental equipment control logic, and multimodal data parsing capabilities, AI agents have significantly addressed bottlenecks in traditional characterization, such as labor-intensive manual operations, time-consuming data analysis, and difficulties in identifying complex systems. Their applications have covered multiple characterization technologies, including optical microscopy, scanning tunneling microscopy (STM), atomic force microscopy (AFM), XRD, SEM, and TEM, and have achieved efficient characterization in diverse systems such as 2D materials, zeolites, alloys, and organic crystals. By rapidly identifying phases and analyzing microstructures, they provide key support for materials discovery.

For instance, in image recognition and analysis, the 2D-TLK model is a lightweight framework for layer identification in 2D materials, integrating a FastViT encoder with a composite decoder combining Lite Reduced Atrous Spatial Pyramid Pooling and Kernels net. Combined with a MAS, it enables high-precision identification and natural language interpretation of thickness and size in 2D materials such as MoS2, WS2, and graphene using optical microscopy. The model achieves an accuracy of 95.48% and demonstrates strong generalization capability and real-time reasoning performance, effectively solving the problem of traditional optical contrast methods that are susceptible to substrate and illumination interference[110]. In the field of STM, a deep learning-based agent system can autonomously perform image quality assessment, surface recognition, and probe adjustment in STM. It enables large-area continuous measurement and molecular statistics under low-temperature conditions (78 K), breaking through the limitations of conventional STM that rely on manual probe adjustment and struggle with long-term stable characterization, thereby significantly enhancing data throughput and reliability[111]. Similarly, in AFM applications, the LLM-driven Artificially Intelligent Lab Assistant (AILA) MAS can coordinate tasks such as calibration, feature detection, mechanical property measurement, and layer identification[112]. These advancements collectively demonstrate how agents transform processes that are heavily dependent on humans, subjective, and low-throughput into automated, intelligent, and repeatable workflows. By overcoming traditional limitations such as operator bias and environmental interference, agents not only enhance measurement accuracy but also enable large-scale, statistically meaningful microstructural analysis.

In the field of crystal structure analysis, AI agents offer new pathways for the automated interpretation of XRD data. For instance, the Crystallography Companion Agent integrates a CNN model trained on physically accurate synthetic datasets, overcoming the overconfidence issue of traditional neural networks by outputting probabilistic phase classifications. This significantly enhances the accuracy and efficiency of phase identification in both organic and inorganic materials, reducing the analysis time from several weeks to just a few hours[113]. CrystalShift combines symmetry-constrained optimization and best-first tree search to enable probabilistic phase labeling and structural parameter extraction from high-throughput XRD data. Without additional phase space information, it can output phase combination probabilities, outperforming existing methods and demonstrating strong robustness in experimental data. Moreover, it can be seamlessly integrated into synchrotron radiation high-throughput workflows[114] [Figure 6]. In addition, in the fields of electron diffraction and scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM) characterization, SerialRED technology automates data acquisition and hierarchical clustering analysis, enabling high-throughput phase analysis of complex polycrystalline mixtures with only a small amount of samples. It can even detect ultra-low content phases that are undetectable by XRD[115]. Meanwhile, an ensemble learning iterative training (ELIT) workflow focuses on ML automation for STEM characterization. By developing a universal language to adapt to various STEM devices, it dynamically adapts to changing imaging conditions, increasing the detection accuracy of atomic positions to over 90%. It also supports in-loop validation with theoretical simulations for structure-property correlation analysis[116]. These agents address one of the most persistent challenges in materials science: reliably and rapidly decoding complex multiphase systems without relying heavily on expert intuition or pre-existing phase databases. By reasoning and handling experimental noise robustly, these systems elevate the objectivity and scalability of structural analysis to a new level. This not only shortens analysis time, but also enables researchers to explore more complex components and discover previously overlooked materials.

Figure 6. Workflow of CrystalShift using the multiphase probabilistic labeling algorithm[114]. Agents can quickly identify phases and analyze microstructures by using characterization devices. Reproduced from npj Comput Mater 11, 148 (2025), under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 license[114]. XRD: X-ray diffraction.

Beyond structural analysis, AI agents also have an impact in the field of material performance testing. In this field, agents automate experimental workflows, manage high-throughput test arrays, and extract meaningful functional properties of materials from complex datasets. For example, in the field of energy materials, the Clio AI agent has achieved autonomous preparation and testing of the ionic conductivity of non-aqueous Li-ion battery electrolytes. The system conducted 42 experiments in just two days and identified the best electrolyte formula with outstanding fast-charging capability[117]. In semiconductor characterization, an agent system autonomously controls a four-degree-of-freedom probe to test the photoconductivity of composite perovskite films. By performing over 3,000 measurements within 24 h, it not only revealed the composition-property trends but also discovered local inhomogeneity and potential defects[118]. Similarly, in mechanical testing, the metal additive manufacturing agent can test the performance of 60 samples per hour, quickly generating the large datasets to establish analysis models associated with process parameters and final tensile strength and elongation[119].

In terms of assisting user operations and tool invocation, the Context-Aware Language Model for Science (CALMS) agent utilizes RAG and tool invocation to enable natural language interaction for operation question answering and hardware control of XRD instruments by retrieving facility documentation, thereby enhancing the usability of advanced characterization facilities for users[120]. Additionally, the advanced instrument operation scheme of human-machine collaboration proposed by Vriza et al. enables agents to coordinate with X-ray nanoprobes and autonomous robotic stations designed for materials synthesis and characterization, optimizing the multi-task workflow through human-machine interaction and iterative learning. This enables the agent to help users better control advanced automated equipment[121].

These advancements highlight the core role of AI agents in material characterization. They can not only process multimodal data, but also rapidly and accurately interpret the microstructure and functional properties of materials, providing a key basis for evaluating synthesis outcomes. Furthermore, through multi-agent collaboration, they can dynamically allocate tasks and offer natural language interaction and explanations, thereby further enhancing the operability and analytical efficiency of experimental characterization. However, there are still several challenges to be addressed in order to realize this vision. Firstly, under extreme experimental conditions or low signal-to-noise ratios scenarios, agents still face limitations in robustly analyzing complex signals, and the reasoning stability under real physical noise requires improvement. In addition, the resource scheduling of the existing system between real-time control and high-throughput tasks needs to be optimized, which affects the overall efficiency in high-throughput experimental scenarios. Finally, given increasingly complex material systems and multidimensional performance indicators, the interpretability and decision transparency of agents remain crucial for achieving end-to-end trusted automation.

Data analysis and conclusion summary

The vast amounts of data generated from materials synthesis experiments and characterization need to be analyzed and summarized into scientific conclusions. In the analysis of materials experimental data, AI agents integrate ML, multimodal data, and cross-scale knowledge reasoning, demonstrating multidimensional capabilities in data integration, key factor identification, and process optimization decision-making. They enable automated parsing of complex experimental data, summarization of conclusions, and optimization of experimental strategies, significantly enhancing the depth and efficiency of data interpretation.

In multimodal data analysis and conclusion summary, agents can integrate experimental and simulation data across sources and scales, revealing underlying mechanisms and universal laws that are difficult to discover by traditional methods. For example, in SSE research, agents revealed a universal principle that hydrides containing neutral molecules (e.g., NH3) have higher ionic conductivity by integrating experimental and computational data from 158 metal hydrides. Through meta-dynamics simulations, a novel “two-step migration” mechanism was discovered, providing theoretical guidance for the design of divalent electrolytes[122]. SciLink automatically transforms experimental data into verifiable scientific claims, quantifies data novelty through literature comparison, and independently proposes subsequent experimental plans, thereby enabling the systematic capture of “serendipitous discoveries” in materials data[123]. Additionally, the PROTeomics Exploration and Understanding System (PROTEUS) agent automatically analyzed 12 proteomics datasets and generated 191 scientific hypotheses[124]. The CellVoyager agent is an AI system that autonomously explores single-cell RNA sequencing datasets guided by prior user analyses. It parses historical data, identifies new mechanisms, and translates expert intuition into verifiable analytical pathways, offering valuable guidance for integrated multi-omics analysis in materials science[125]. Overall, these studies demonstrate how agents not only integrate multimodal and cross-scale data but also reveal potential mechanisms and generate novel hypotheses, effectively transforming raw experimental data into interpretable and actionable scientific knowledge.

In experimental design and optimization, agents achieve dynamic regulation and multi-objective optimization of synthetic pathways and material formulations through RL, generation models, and real-time data fusion. Taking the development of ultra-high-performance concrete materials as an example, an agent based on RL analyzes historical experimental data to construct a Markov decision process model, enabling dynamic adjustment of material ratios and process parameters. Through six rounds of experimental iterations, it increased the compressive strength from 55 to 221 MPa while reducing costs by over 25%. It also identified the key strategy of balancing strength and cost through the regulation of cement and silica fume content[126]. In the synthesis of MOFs, MOFsyn is a framework leveraging LLMs to guide the efficient synthesis and performance optimization of MOFs. It integrates literature knowledge with real-time experimental data to analyze relationships among synthesis conditions, characterization results, and catalytic performance. It identified Ni0 content and H2 adsorption strength as the core factors influencing catalytic activity and proposed a stepwise reduction strategy to guide the optimization of MOF synthesis. This enabled Ni@UiO-66(Ce)-R2T1 to achieve 100% conversion and selectivity in olefin hydrogenation reactions[127]. For the design of transition metal complexes, LLM-EO, which integrates LLMs into evolutionary optimization, combines generative models with multi-objective optimization, revealing the regulatory effects of strong electron-withdrawing ligands on performance using only 20 experimental samples. In a chemical space of 1.37 million candidates, it identified eight top-20 high-performance materials using only 200 evaluations, highlighting the advantage of agents in analyzing structure-property relationships from experimental data[128]. It can be seen from these that in the experimental optimization, agents not only achieved a leapfrog improvement in performance, but also revealed the key factors and regulatory mechanisms that affect material performance in a data-driven way.

In summary, AI agents transform data analysis from an isolated, post-hoc step into a real-time feedback loop in the experimental process. They efficiently parse high-dimensional materials data, dynamically integrate knowledge, and perform cross-scale reasoning. This enables the discovery of hidden patterns and novel mechanisms from complex datasets, the proposal of verifiable new hypotheses, and the optimization of experimental pathways. Consequently, they provide direct, data-driven decision support for materials science research, significantly improving experimental efficiency and scientific discovery.

This section demonstrates the deep integration of AI agents throughout the entire process of materials synthesis and characterization. From the exploration of material synthesis processes, automated characterization to data analysis and conclusion summary, agents are shifting the paradigm of materials synthesis from “experience-driven” to “intelligence-driven”. They not only significantly enhance experimental efficiency but also make it possible to “synthesize on demand” materials with targeted properties.

AGENTIC MATERIALS CREATION

As the capabilities of AI agents in materials design and synthesis continue to mature, the trend of their development is to form SDLs. The SDL is the ultimate embodiment of materials AI agents, integrating the entire workflow for materials creation from design and synthesis to validation. Through a trinity architecture of “hardware-software-agent”, it deeply integrates LLMs, MAS, and robotics technologies. This enables a fully autonomous closed loop from experimental design, execution, to analysis and optimization, thereby transforming the paradigm of materials creation in unprecedented ways.

The development of agent-driven SDLs is a progressive evolution, clearly reflecting the synergistic advancement of AI and robotics technologies. Early groundbreaking work, such as the mobile robotic chemist, broke the constraints of traditional fixed workstations. By operating freely in a standard laboratory and utilizing batched Bayesian search algorithms, it autonomously conducted 688 photocatalyst experiments in eight days and screened out a hydrogen evolution photocatalyst with sixfold higher activity, demonstrating the feasibility of deploying automated researchers rather than mere automated instruments[129]. A-Lab, an autonomous laboratory for the solid-state synthesis of inorganic powders, further achieves autonomous synthesis of inorganic powders by leveraging computational predictions, literature data, and ML. Within 17 days, it successfully synthesized 41 novel compounds, highlighting the potential of the integration of AI and robotics to accelerate materials discovery[130] [Figure 7A]. Subsequently, the flow chemistry automation platforms combined liquid processors, syringe pumps, adjustable continuous-flow photoreactors, and in-situ NMR spectroscopy, and achieved automated optimization and scale-up of photocatalytic reactions through closed-loop Bayesian optimization strategies[131].

Figure 7. (A) Autonomous materials discovery with the A-Lab[130]; (B) LLM-based multiagent system, ChemAgents[138]. Multi-agent collaborative architecture enables AI agents to complete complex research tasks. Figure 7A is reproduced from Nature 624, 86-91 (2023), under CC BY 4.0 license[130]. Figure 7B is reproduced from J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2025, 147, 15, 12534-12545, with permission from American Chemical Society[138]. LLM: Large language model; AI: artificial intelligence.

With the development of LLMs, the deep empowerment of LLMs has driven the evolution of AI agents from performing single functions to handling multifaceted tasks, significantly enhancing the cognitive and decision-making capabilities of SDLs. For instance, systems such as Coscientist (a multi-LLMs-based intelligent agent)[132] and ChemCrow (an LLM-based chemistry agent for tasks in organic synthesis, drug discovery, and materials design)[133] used LLMs as core planners. These agents autonomously perform complex tasks, including organic molecule synthesis and reaction optimization, by invoking various chemical tools and automated experimental equipment. Chemist-X further employs RAG to integrate domain knowledge, enabling precise recommendations of reaction conditions. Through real-time interaction with automated robotic systems, it achieves end-to-end experiment validation without human intervention. This demonstrates the capacity of LLM-driven agents to autonomously design, plan, and execute complex experiments[134].