Bioinspiration for bioiontronics

Abstract

Ions and small molecules form the basic language of biology, enabling numerous biological signaling activities. Biology has used the language of ions since the beginning of life, and scientists are only now beginning to catch up. The field of bioiontronics is emerging, aiming to communicate with living matter through ions and molecules for the detection and modulation of biological activities. Bioiontronics is an interdisciplinary field that originates from iontronics, the active control of ion transport. Specifically, bioiontronics refers to iontronic devices that interface with biological systems, incorporate biological components, or employ biomimetic designs. Therefore, understanding the ionic nature of biological systems is essential to bioiontronics and may inspire future breakthroughs. Here, we summarize ionic phenomena across different biological scales and examine their ionic mechanisms. We further summarize the bioinspired endeavors of bioiontronics, including energy harvesting and storage, sensing, signal processing, and biointerfaces. Finally, we outline the potential applications and challenges of mimicking natural ionic processes. The Review serves both as a source of information and as a benchmark and encouragement for further bioiontronic developments.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

Life communicates and powers itself with ions. Based on ion distribution and transport, biological systems execute diverse processes, including maintaining osmotic equilibrium, conducting neural signals, and facilitating metabolism. Conversely, impaired ion transport disrupts physiological balance and triggers disease[1,2]. In aqueous media and at biointerfaces, ion fluxes can be rapidly established, modulated, and reversed by changes in gradients and permeability, providing a versatile physical basis for biological signaling and energy conversion. Understanding the ionic gradients and the bioelectricity they generate is therefore central to explaining how organisms function and how their activities can be regulated[3].

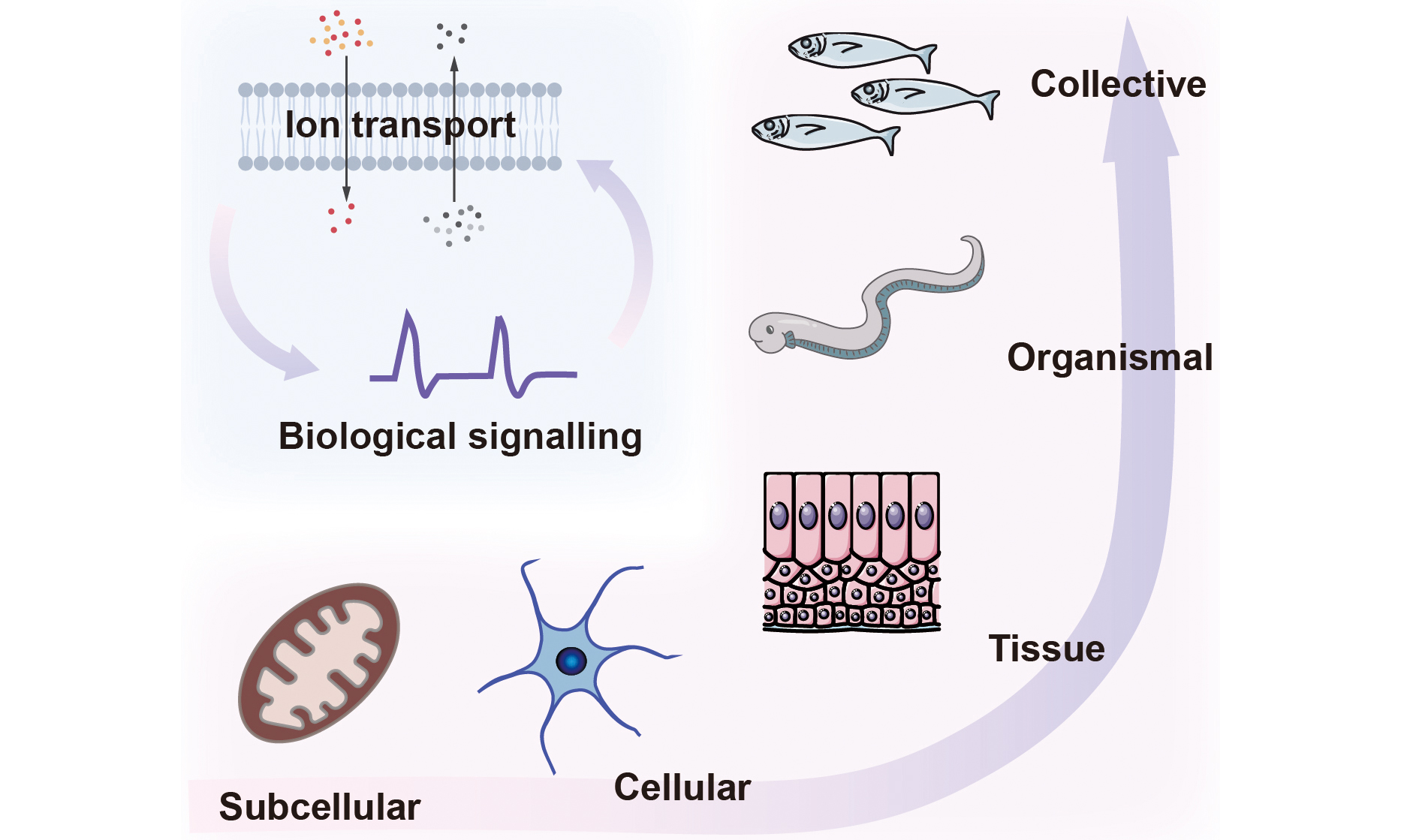

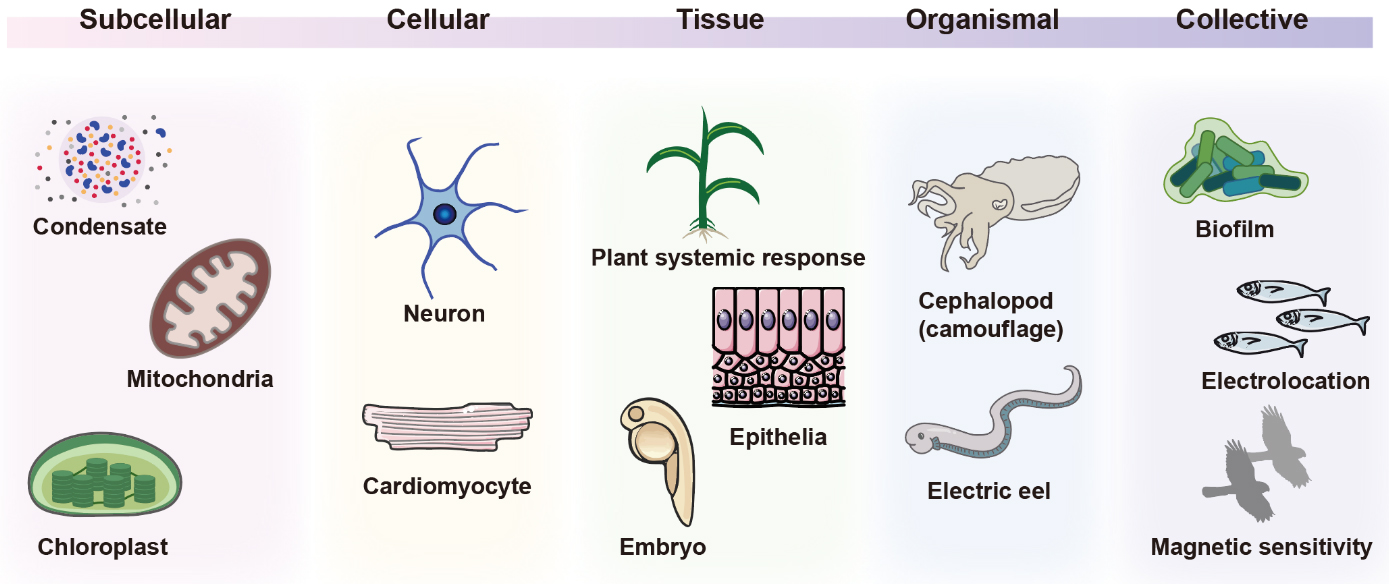

Bioelectricity arises from ionic gradients and the intrinsic ionic conductivities of cells, produced by the selective distribution of ions and charged biomolecules across membranes. Ion channels, pumps, gap junctions, and solute carriers establish these gradients that sustain normal physiology[4]. Although rooted in single cells, bioelectric phenomena scale up to tissues, organs, and whole organisms, enabling cellular collectives with information-storage and processing capabilities beyond those of isolated cells. For instance, neural bioelectricity in the brain mediates coordinated actions in three-dimensional space, while non-neural bioelectricity influences developmental and large-scale regenerative processes[5-7]. Here, we focus on the ionic nature and bioelectric phenomena spanning diverse tissue scales. Examples include nanoscale biomolecular condensates that reshape local ion partitioning, sub-microscale organelles that convert light or redox energy into proton gradients, microscale cellular excitability in neurons and muscle, tissue-scale electric fields that guide wound healing and morphogenesis, and organismal-scale electric organs in electric fish [Figure 1]. Representative examples at these scales, along with their typical sizes and ionic parameters, are summarized [Table 1].

Figure 1. Biological ionic processes operate across scales, from the molecular scale to the collective scale.

Typical geometric and ionic parameters across various biological scales

| Scale | Example | Approximate feature size | Ionic parameters |

| Molecular | Biomolecular condensates[8] | Diameter < 1 μm (inside Escherichia coli) | Alter the membrane potential |

| Organelle (subcellular) | Chloroplast[9,10] | Long axis 5-10 μm Short axis 2-4 μm Thickness 2-3 μm | ΔpH ~ 1.8-2.1 ΔΨ ~ 10-20 mV |

| Mitochondria[11,12] | Diameter 0.5-1.0 μm Length 1.5-3.0 μm | 180-200 mV | |

| Cellular | Neuron[13,14] | Soma: diameter 4-100 μm Axon: length 1 μm to > 1 m | -30 ~ -90 mV (RP) |

| Cardiomyocyte[15] | Diameter 10-20 μm Length 80-150 μm | -80 ~ -90 mV (RP) | |

| Tissue | Plant systemic response[16] | Propagates across a leaf or entire plant | ~ 80-150 mV (Mimosa pudica) |

| Epithelia[17] | Thickness 35-150 μm | 10-60 mV (human transepithelial potential) | |

| Organismal | Electric eel[18,19] | Max body length 2.5 m | ~ 150 mV per electrocyte; Open-circuit voltage of the organ > 600 V |

| Collective | Collective electrosensing (electric fish)[20] | Body length 11-19 cm (Gnathonemus petersii) | Peak current ~ 50 μA (conspecific-induced electrical image) |

| Electroactive biofilm[21,22] | Thickness 100-200 μm; Area up to m2 | Conductivity ~ 5 mS/cm (Geobacter sulfurreducens) |

Iontronics is the study of systems in which ions, rather than electrons, act as charge carriers for signal transmission, transduction, and energy conversion. By leveraging ion transport, electrochemical interactions, and electron-ion coupling, iontronic systems advance intelligent sensing and sustainable energy harvesting[23-25]. In nature, ionic processes drive phase separation at the molecular scale, facilitate signal transmission and motility at the cellular and organ scales, and even propel energy and information flow at the individual and collective scales. These natural ionic processes have inspired design principles for artificial devices, including power sources, sensing systems, computational units, and biointerfaces. Leveraging the universal ionic language that connects biology and artificial devices, bioiontronics extends iontronics into the biological domain in three ways. First, bioiontronics could communicate with living systems at biointerfaces, reading and writing biological activities through ionic mechanisms[26-29]. Second, bioiontronics may incorporate biological components through bottom-up approaches to control ion transport, such as the integration of membrane channels into lipid bilayers[30-33]. Third, bioiontronics could mimic natural ionic processes to build iontronic machineries[18,34], which is the focus of this Review. Here, we describe the bioinspired pathway from biological phenomena to the design of bioiontronics, introduce several categories of bioinspired applications, and outline future directions and challenges in bioiontronics. Together, bioiontronics bridges living matter and artificial systems by centring on ionic processes and their biological implications.

BIOLOGICAL IONIC PROCESSES ACROSS SCALES

Molecular and subcellular scale

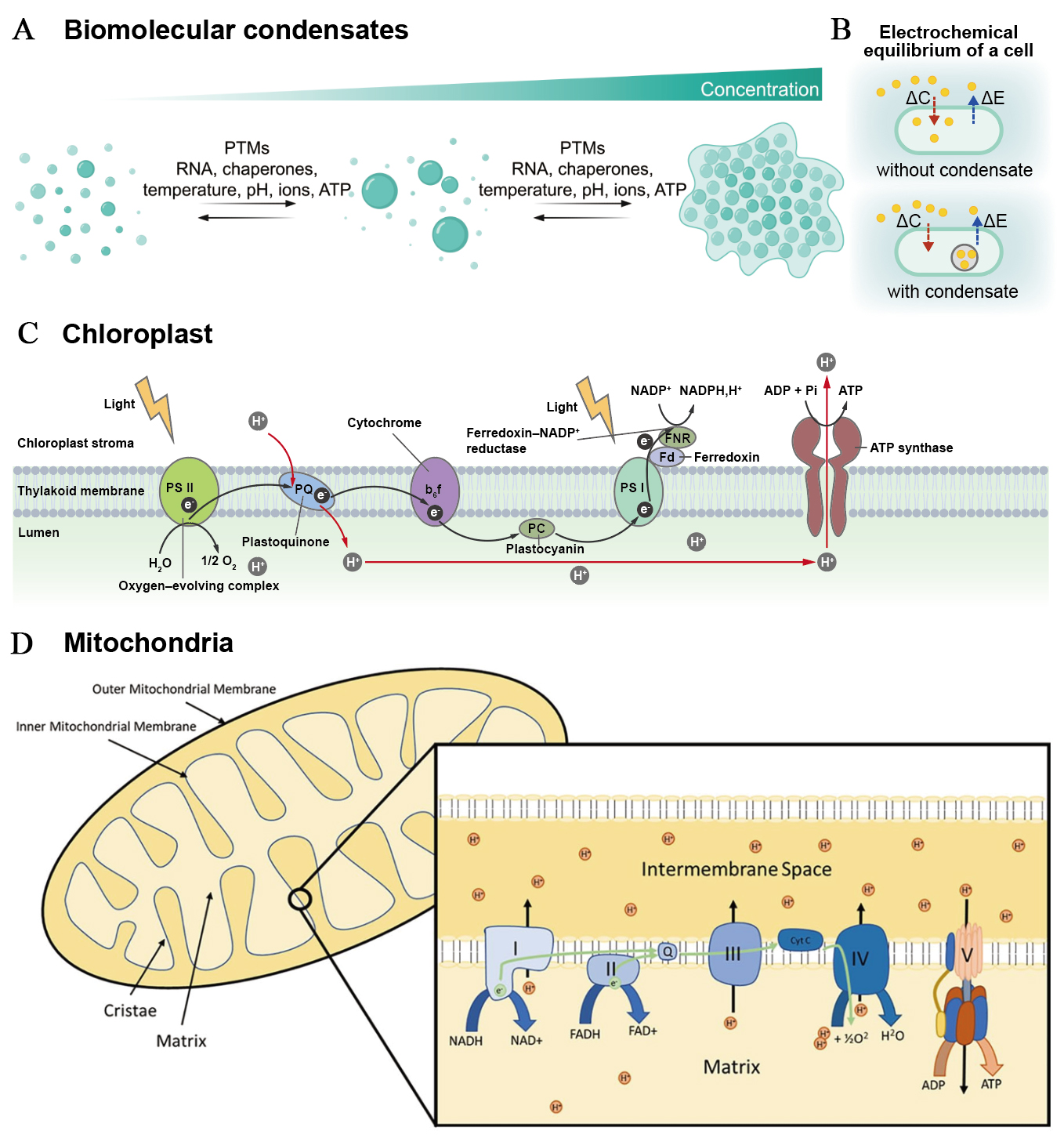

At the molecular and subcellular scale, ions and their associated electrochemical potentials are the key drivers of cellular functions and energy conversion processes[35,36]. We focus on the ionic processes in biomolecular condensates, chloroplasts, mitochondria, and synaptic vesicles for illustration [Figure 2]. In nature, there are many other biological phenomena that involve ions and ionic effects, which are not covered in this Section.

Figure 2. Molecular and subcellular ion dynamics. (A) Mechanisms of biomolecular condensation via phase separation: intrinsically disordered regions and RNA scaffolds form multivalent interactions to drive nucleation and subsequent protein-RNA recruitment. Post-translational modifications (PTMs) tune assembly/disassembly by altering interaction surfaces, while temperature, pH, ionic strength, and crowding conditions set phase-separation thresholds. This figure is quoted with permission from Choi et al.[37]; (B) Diagram showing how condensate formation shifts the intra- versus extracellular electrochemical balance, impacting membrane voltage; (C) Linear electron transport across the thylakoid: PSII uses light energy to oxidise water and reduce plastoquinone, cytochrome b6f transfers electrons to plastocyanin while releasing protons to the lumen, PSI reduces ferredoxin and FNR generates NADPH; the resulting proton motive force powers ATP synthase; (D) Overview of mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation organisation: electron carriers feed complexes I-IV, protons are pumped across the inner membrane to establish a proton electrochemical gradient, and ATP synthase at cristae edges uses this gradient; carriers and supercomplexes coordinate flux and regulation. This figure is quoted with permission from Middleton et al.[38]. ΔC: Change in concentration; ΔE: change in electrochemical potential; NADP+: nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate; PSI: photosystem I; PSII: photosystem II; FNR: ferredoxin-NADP+ reductase; PC: plastocyanin; ADP: adenosine diphosphate; NADPH: reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate; PQ: plastoquinone; NADH: reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide; NAD: nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide; FADH: reduced flavin adenine dinucleotide; FAD: flavin adenine dinucleotide.

Biomolecular condensates formed through liquid-liquid phase separation can enrich or exclude specific ions, thereby regulating the intracellular ionic environment, including spatial pH and ion distributions[8,37,39] [Figure 2A]. Typically, cells regulate intracellular ion content through ion channels to modulate membrane potential. Since membrane potential is sensitive to the intracellular electrochemical environment, condensate formation alters this equilibrium by establishing a new intracellular ion distribution balance, thereby modifying membrane potential[8,40,41] [Figure 2B]. Further research confirms that condensate-mediated regulatory effects can modulate cellular physiology by altering intercellular communication with the environment. For instance, bacteria harboring condensates exhibit greater susceptibility to positively charged antibiotics compared to those without condensates. This may arise from condensate-mediated hyperpolarisation of the membrane potential, which enhances the uptake of positively charged antibiotics[8]. Intracellular ion homeostasis is crucial for cellular physiology, as precise regulation of ion concentrations and their spatial distribution underpins intracellular biochemical activities, including transcription, translation, and antibiotic resistance. Condensate formation modulates the spatial distribution of specific ions within cells, thereby providing a complementary mechanism to ion channels for regulating cellular electrochemical equilibrium[42,43].

Chloroplasts constitute a highly optimised bioiontronic energy-conversion system. During illumination, water oxidation at the oxygen-evolving complex of photosystem II (PSII) releases electrons and pumps protons (H+) into the thylakoid lumen[44-47] (see Table 2 for acronyms used in the Review). The electrons are passed to plastoquinone, which combines with two protons from the stroma to form plastoquinol. Cytochrome b6f oxidizes plastoquinol and releases protons into the lumen, transferring electrons via plastocyanin to photosystem I (PSI). Light-excited PSI oxidises plastocyanin and transfers electrons to ferredoxin, which then reduces nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADP+) to reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) through the ferredoxin-NADP+ reductase (FNR). These reactions constitute the linear electron transport chain from water to NADP+ and build a proton motive force across the thylakoid membrane that drives adenosine triphosphate (ATP) synthase to produce ATP from adenosine diphosphate (ADP) and inorganic phosphate[48,49] [Figure 2C]. These tightly coupled electron and proton transfers convert light energy into electrochemical gradients and chemical fuels (ATP and NADPH), demonstrating a sophisticated biological energy converter.

Abbreviations

| Acronym | Description |

| ΔC | change in concentration |

| ΔE | change in electrochemical potential |

| ΔΨ | membrane potential |

| ACh | acetylcholine |

| ADP | adenosine diphosphate |

| AP | action potential |

| ATP | adenosine triphosphate |

| FAD | flavin adenine dinucleotide |

| FADH | reduced flavin adenine dinucleotide |

| GLR | glutamate receptor |

| NAD | nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide |

| pH | proton concentration |

| PSI | photosystem I |

| PSII | photosystem II |

| Q | ubiquinone |

| RP | resting potential |

| NADP+ | nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate |

| NADPH | reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate |

| FNR | ferredoxin–NADP+ reductase |

| PC | plastocyanin |

| PQ | plastoquinone |

| NADH | reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide |

Comparable bioiontronic processes operate throughout other organelles and enable various metabolic and signaling functions through dynamic inter-organellar communication. Mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation is carried out by the electron transport chain (Complexes I-V) embedded in the inner membrane. Reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NADH) and reduced flavin adenine dinucleotide (FADH2) generated from the tricarboxylic acid cycle deliver electrons to Complexes I and II, respectively, which are transferred via ubiquinone and cytochrome c to Complex IV, where molecular oxygen is reduced to water. During electron transfer, the complexes pump protons into the intermembrane space, generating a proton motive force across the inner membrane[50] [Figure 2D]. This generates an electrical potential and energy across the membrane in the form of a pH gradient. When protons flow back into the membrane through ATP synthase in the reverse

Our examples show how biology uses ions and bioiontronic machineries at the molecular and subcellular scales, transforming metabolic energy into spatiotemporally precise ionic signals that sustain homeostasis and information processing.

Cellular scale

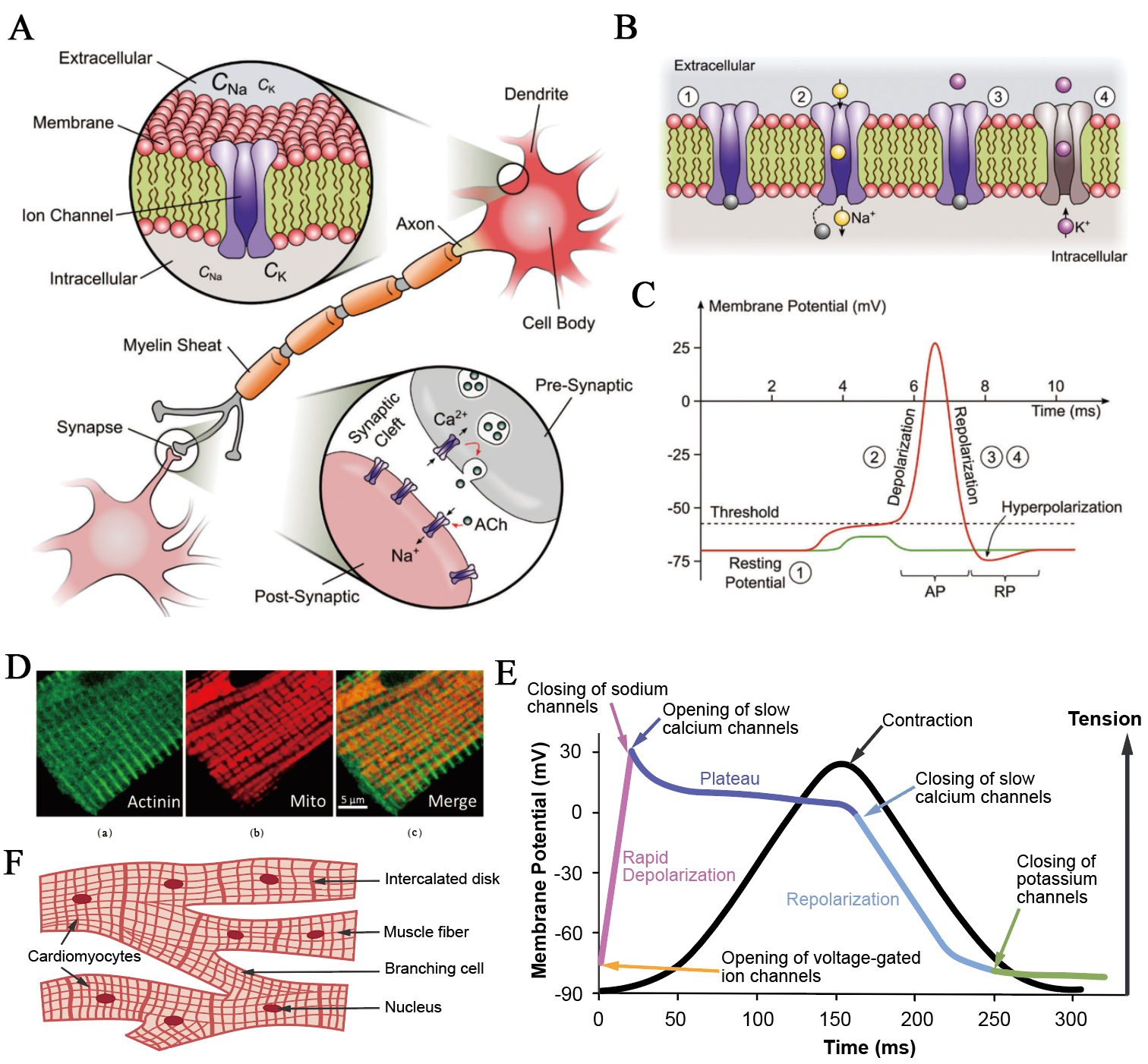

At the cellular scale, ion flows across membranes govern how living cells transform chemical gradients into electrical and mechanical energy. Through the coordinated action of ion channels and pumps, cells maintain dynamic voltage distributions, thereby precisely regulating excitability and signal transduction[56]. This level of organisation marks the transition from local, organelle-based electrochemical events to coordinated whole-cell phenomena that underlie neurotransmission, muscle contraction, and metabolic regulation [Figure 3].

Figure 3. Ionic mechanisms in the electrophysiological activities of excitable cells. (A) A synaptic connection between two neurons. The upper inset shows the cross-section of a neuronal membrane with extracellular and intracellular ionic environments, while the bottom inset magnifies the synaptic cleft, highlighting vesicular neurotransmitter release and postsynaptic ion-channel activation. This figure is quoted with permission from Chen et al.[57]; (B) Sequential states of voltage-dependent Na+ and K+ channels during the generation of an action potential, showing membrane depolarisation, Na+ channel activation, and subsequent K+-mediated repolarisation. This figure is quoted with permission from Chen et al.[57]; (C) Transient membrane potential trace of a neuron illustrating an all-or-none action potential (red), by comparison with a subthreshold stimulus that fails to trigger firing (green). This figure is quoted with permission from Chen et al.[57]; (D) Simultaneous fluorescent and immunofluorescent confocal imaging analysis of mitochondria and sarcomeric Z-line (actinin) tubulin beta-II in rat cardiomyocyte. (a): Z-line (actinin); (b): Mitochondria; (c): Merge image. Scale bar, 5 µm. This figure is quoted with permission from Kuznetsov et al.[58]; (E) Ionic basis of the cardiac action potential and excitation-contraction coupling; (F) Structure of intercalated disks connecting adjacent cardiomyocytes. Gap junctions within these regions enable direct ionic current flow, ensuring synchronous propagation of action potentials and coordinated contraction across the cardiac syncytium. AP: Action potential; RP: resting potential; ACh: acetylcholine.

Neurons are the archetypal electrically excitable cells. Their membranes separate the extracellular and intracellular ionic environments, maintaining distinct sodium and potassium concentrations through selective permeability and active transport [Figure 3A]. The resting potential of approximately -75 mV arises mainly from K+ leak currents and the electrogenic action of the Na+/K+-ATPase. Synaptic input depolarises the membrane toward a threshold near -55 mV, at which voltage-gated Na+ channels open within milliseconds, allowing Na+ influx and producing a rapid rise in membrane potential[57,59]. During this phase, the voltage approaches the Na+ equilibrium potential of about +60 mV, reaching a spike amplitude of +30 to +40 mV. The delayed activation of voltage-gated K+ channels restores the resting potential through repolarisation and transient hyperpolarisation [Figure 3B and C]. Communication between neurons occurs across synapses, where neurotransmitter release and postsynaptic ion-channel activation couple electrical and chemical signaling [Figure 3A]. In myelinated axons, action potentials propagate rapidly via saltatory conduction at nodes of Ranvier, where local ionic currents recharge the membrane. Recent studies have also shown that synchronised activity of neighboring axons can induce weak extracellular electric fields that can modulate adjacent membranes, a phenomenon termed ephaptic coupling[60-62]. Such field-mediated interactions add an additional iontronic dimension to neuronal communication, allowing subtle coordination of timing and synchrony across densely packed neural fibers[63]. The cyclical gating of Na+ and K+ channels and the precision of synaptic transmission together create the all-or-none action potential that enables long-distance, high-fidelity information transfer in nervous systems.

Cardiac muscle cells employ similar ionic principles as neurons but integrate them with mechanical output. The structural organisation of human cardiomyocytes features a well-developed transverse-axial tubular system that distributes excitation signals deep into the cytoplasm[58,64,65] [Figure 3D]. At rest, the membrane potential of atrial and ventricular cardiomyocytes typically lies between -70 and -90 mV, maintained primarily by inward rectifier K⁺ currents and sustained by the Na+/K+-ATPase[15,66]. Upon depolarisation, voltage-gated Na⁺ channels open, driving the potential up to about +20 mV and initiating the cardiac action potential that triggers excitation–contraction coupling [Figure 3E]. During the plateau phase, L-type Ca2+ channels permit Ca2+ influx, which in turn induces Ca2+ release from the sarcoplasmic reticulum through ryanodine receptors. The ensuing rise in cytosolic Ca2+ activates troponin C and initiates cross-bridge cycling, translating electrical excitation into mechanical contraction. Repolarisation follows as K+ channels reopen and Ca2+ is re-sequestered by sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase pumps or extruded through Na+/Ca2+ exchangers, restoring ion gradients and membrane potential[65,67]. Electrical continuity between adjacent cardiomyocytes is maintained via intercalated disks, where gap junctions mediate direct ionic current flow and synchronise the spread of action potentials across the myocardium[68] [Figure 3F]. This coupled network allows the heart to function with syncytial-like electrical and mechanical integration, ensuring precise temporal coordination of depolarisation, Ca2+ signaling, and contraction in each heartbeat.

Comparable ionic mechanisms link metabolism to excitability in other cell types. In pancreatic β-cells, for instance, glucose metabolism raises the ATP/ADP ratio, which closes ATP-sensitive K+ channels and depolarises the membrane. The subsequent opening of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels triggers Ca2+ influx, thereby initiating insulin secretion[69]. Smooth muscle cells similarly exhibit rhythmic depolarisations and Ca2+ oscillations that couple ionic activity to contractile function[70]. In these different cells, the controlled movement of ions enables the conversion of chemical energy into mechanical motion or other physiological functions.

Tissue scale

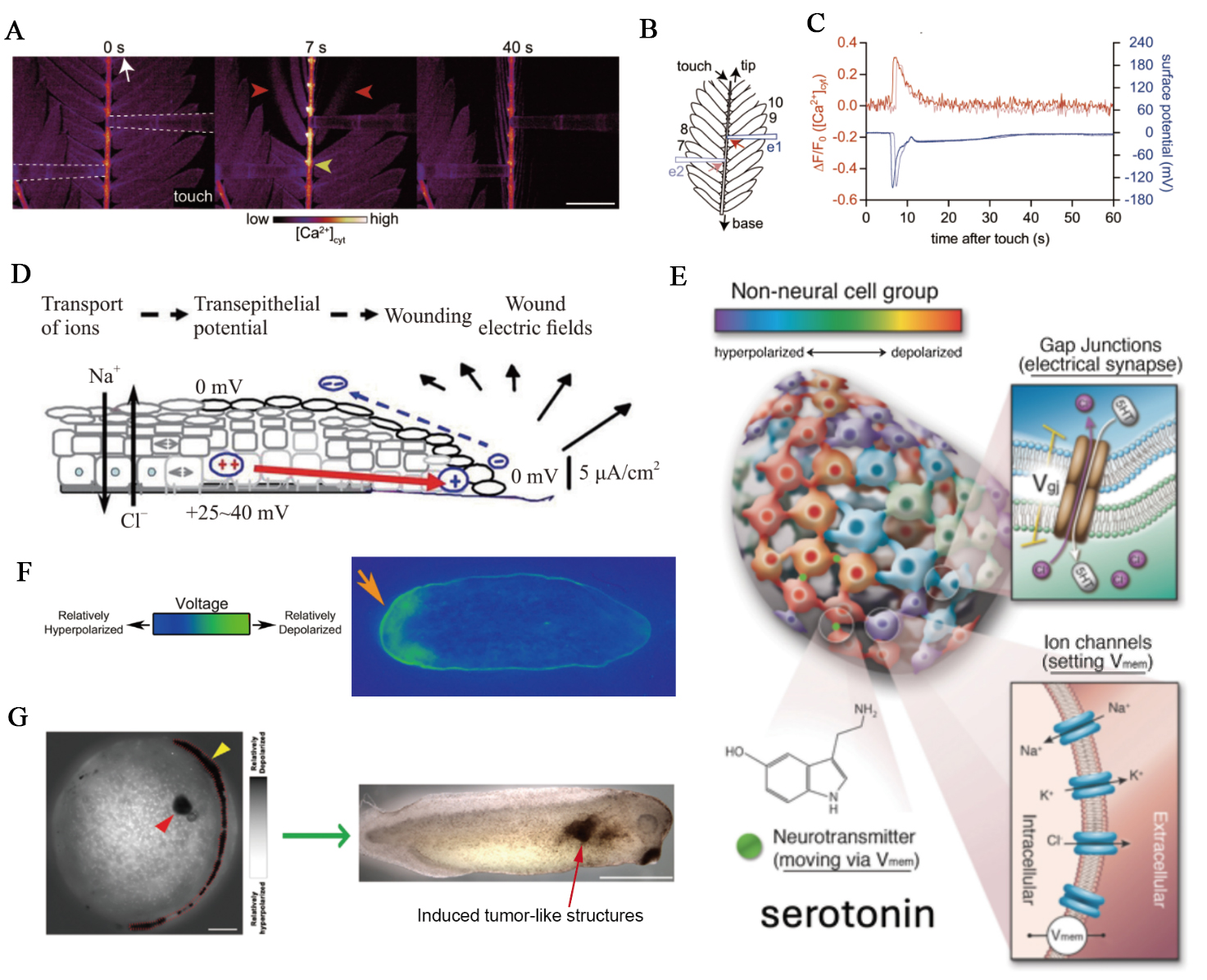

At the tissue scale, long-range ion transport and electric fields (termed bioelectricity) mediate diverse physiological events ranging from plant signaling to animal morphogenesis [Figure 4]. This section demonstrates how ionic processes and bioelectricity extend from single-cell excitability to the coordination of multicellular behavior.

Figure 4. Ionic mechanisms in tissue-scale bioelectric signaling. (A-C) Coupled Ca2+ and electrical signaling in Mimosa pudica: (A) simultaneous imaging and electrophysiology showing that gentle touch (white arrow, 0 s) evokes a cytosolic Ca2+ rise (yellow arrowhead) accompanied by leaflet movement (red arrowhead) (scale bar, 5 mm); (B) schematic of the experimental setup showing electrode positions (blue rectangles e1, e2) and regions of interest (red arrows) 1 mm from the electrodes; (C) changes in [Ca2+]cyt and surface potential in response to touch. These figures are quoted with permission from Hagihara et al.[16]; (D) In animal epithelia, disruption of the barrier collapses the transepithelial potential, generating a lateral electric field that directs cell migration and wound closure. This figure is quoted with permission from Jia et al.[17]; (E) Developing tissues form bioelectric networks where ion channels and gap junctions establish structured voltage domains that guide morphogenesis. This figure is quoted with permission from Hansali et al.[71]; (F) Voltage gradient across the anterior/posterior axis of planarian flatworms, visualized by a bioelectric reporter dye, which determines the location and number of heads. Orange arrowhead indicates a depolarised region, which will develop a head. This figure is quoted with permission from Durant et al.[72] (G) Early depolarised focus predicts a later tumor-like outgrowth. Left, membrane-potential imaging shows a localized depolarised region (red arrowhead). Depolarisation along the neural tube (yellow arrowhead) marks the characteristic bioelectric pattern of neurulation. Right, the embryo later develops an induced tumor-like structure at the position corresponding to the earlier depolarised focus. Scale bars: 150 μm (left); 1 mm (right). This figure is quoted with permission from Chernet et al.[73]. [Ca2+]cyt: Cytosolic Ca2+ concentration; Vmem: membrane potential.

As previously mentioned, the central nervous system in animals constitutes a highly complex signaling network, with neurons communicating via various neurotransmitters. Although plants lack the cell types and structures specific to animals, they appear to possess the fundamental components for long-distance signal transmission, such as ion channels and second messengers[74-76]. Research indicates that plants can coordinate long-distance responses at the tissue and organ scales by coupling calcium signals with electrical signals[77,78]. Studies in Arabidopsis thaliana reveal that local wounding activates glutamate receptor (GLR) channels (e.g., GLR3.3), launching self-propagating Ca2+ waves accompanied by membrane depolarisation along the vasculature into distal tissues. A Ca2+/calmodulin-mediated negative-feedback mechanism desensitises GLR3.3 and thereby shapes the duration of these systemic signals[79]. In parallel, simultaneous recordings in Mimosa pudica show that touch or wounding elicits cytosolic Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]cyt) elevations that travel along leaflet veins and rachilla in tight temporal lockstep with surface potential changes and leaflet movements [Figure 4A–C], establishing that rapid Ca2+ waves and electrical signals are co-propagating carriers that drive pulvinar motor responses and systemic defence behaviors[16].

In animal epithelia, endogenous bioelectric fields emerge as both acute injury signals and steady-state organisers of tissue architecture. Under intact conditions, many epithelia maintain a transepithelial potential difference on the order of millivolts, generated by directional ion transport and sealed by tight junctions, which makes the basal side electrically distinct from the apical surface. When the epithelial barrier is breached, this potential is locally short-circuited and the wound site becomes electrically negative relative to surrounding intact tissue, establishing a lateral electric field that can reach tens to hundreds of millivolts per millimeter near the wound edge[80] [Figure 4D]. This injury-induced field drives directed migration of keratinocytes, fibroblasts, and immune cells toward the lesion, and persists until re-epithelialization restores the barrier and eliminates the voltage drop[81,82]. Beyond endogenous cues, externally applied fields can actively reshape lumenized epithelia by boosting ion transport and water influx, inflating kidneyoids and gut organoids and altering their three-dimensional geometry. These electro-inflation effects highlight that tissue size and shape can be steered by tuning the electrical microenvironment, with mechanics and ion flow tightly coupled at the organoid scale[83,84]. Consistent with this view, experimentally imposing controlled fields aligned with, or opposed to, the natural transepithelial potential difference can either reinforce cohesive junctional organisation and preserve a flat, confluent monolayer, or disrupt junctional actin, generate domed cell morphologies, and induce multicellular mounding and extrusion. In this view, the tissue-scale electric field is not merely a by-product of ion pumping; it is an active mechanical input. Field-driven ion flux can generate electromechanical stress on the order of kilopascals at the cell-substrate interface, biasing whether an epithelium spreads, stratifies, or breaks into protruding aggregates, and even rescuing defective epithelia with weakened adhesion by compressive stabilization[85]. These findings position transepithelial voltage and its associated current loops as physiologically meaningful control parameters for wound closure, epithelial integrity, and long-term tissue morphology, linking ionic transport to collective cell behavior at the tissue scale.

During embryonic development, bioelectric patterning acts as an instructive control layer for tissue organisation and morphogenesis[86,87]. All cells, not just neurons, possess ion-channel proteins and pumps that establish a resting membrane potential (Vmem), which serves as a key regulator of cellular behaviors, including proliferation, differentiation, apoptosis, migration, and polarity[88]. Developing tissues form coupled bioelectric networks in which individual cells maintain distinct Vmem values, and gap junctions propagate these voltage states across neighboring cells to generate spatially structured electrical domains at the tissue scale[71,89] [Figure 4E]. These patterned voltage landscapes emerge very early - in some vertebrate systems as early as the two-cell stage - and persist as stable electrical prepatterns that carry positional information for large-scale anatomy. Optical mapping of membrane potential across regenerating and developing tissues shows that these spatial distributions correlate with future morphological outcomes, such as the anterior–posterior polarity in planarian body fragments [Figure 4F] and the patterned ‘bioelectric face’ in early frog ectoderm, which anticipates the location of eyes, mouth, and branchial structures[72,90,91]. Local deviations from these tissue-scale electrical states are also associated with pathological transitions: cells that depolarise relative to their surroundings can electrically decouple from normal patterning control and initiate proliferative, tumor-like programs[73] [Figure 4G]. Importantly, these ionic phenomena and bioelectric states are not mere by-products of morphogenesis but active regulators of it. By modulating ion-channel activity or gap-junctional connectivity, transient ion transports or perturbations of bioelectric networks may redirect developmental trajectories - inducing ectopic organ formation, restoring normal morphology after perturbation, and even reprogramming tissue identity. These insights not only deepen our understanding of developmental control but also reveal new opportunities for bioiontronic therapeutic strategies, in which targeted manipulation of voltage states could guide tissue regeneration and repair through programmable ionic circuits, thereby laying conceptual foundations for future ‘morphoceuticals’[92-94].

At this level, ionic processes not only transmit signals across tissues but also mediate growth, repair, and morphogenesis within organisms. These phenomena hold potential to inform the development of novel bioiontronic therapeutics.

Organismal and collective scales

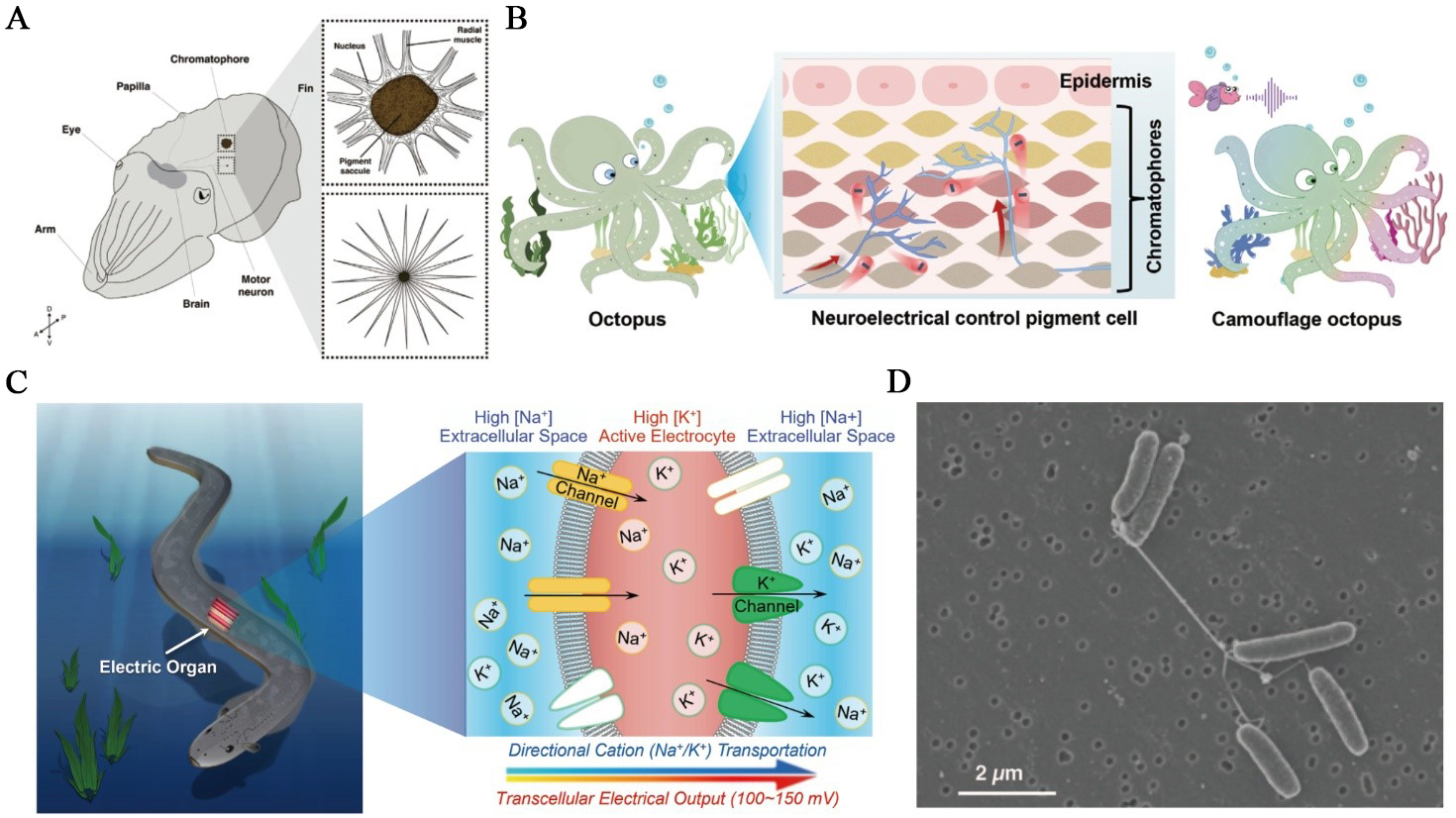

At the organismal and collective scales, biology manifests as coordinated bioiontronic machinery that bridges physiology, behavior, and environmental interactions [Figure 5].

Figure 5. Biological ionic processes at organismal and collective scales. (A) Cephalopod skin is covered in thousands to millions of chromatophores - expandable neuromuscular organs that are controlled by motor neurons projecting from the brain. Upper box: expanded chromatophore; lower box: relaxed chromatophore. This figure is quoted with permission from Shook et al.[95]; (B) Schematic of the cephalopod reflex arc illustrating how sensory inputs are converted into neural signals that drive chromatophore muscle contraction, enabling rapid, reversible color change. This figure is quoted with permission from Yu et al.[96]; (C) Electrophorus electricus and a schematic of its electric organ. The right image depicts ion fluxes during a discharge, with the innervated posterior membrane becoming Na+-permeable and the anterior side K+-selective, so that many electrocytes in series collectively produce a high-voltage output. This figure is quoted with permission from Zhang et al.[27]; (D) Scanning electron micrograph of S. oneidensis MR-1 grown under electron-acceptor-limited conditions, showing bundles of pili-like, electrically conductive nanowires that bridge cells. Scale bar, 2 µm. This figure is quoted with permission from Gorby et al.[97]. MR: Manganese reducer.

In cephalopods, camouflage is implemented by a distributed, electrically controlled skin display that converts sensory context into rapid optical output via a brain-skin motor pathway[98-100]. Cephalopod camouflage is driven by an ionic cascade in which sensory inputs are encoded as spikes that trigger Ca2+-dependent neurotransmission at chromatophore motor terminals. The ionic processes depolarise radial muscle fibers, and convert ionic current into mechanical expansion of pigment sacs on subsecond timescales[95,96] [Figure 5A and B]. Iridescence provides a slower, secondary channel in which neural input activates intracellular cascades in iridophores, leading to the condensation of phosphorylated reflectin proteins and water efflux. The process reduces platelet spacing, and thereby retunes structural color on tens-of-seconds timescales, extending ionic control to structural-color modulation[99]. The core mechanism is the retina → optic lobe → lateral basal lobe → chromatophore lobes pathway that projects motor commands to skin, implementing ‘stimulus → ionics → mechanics → optics’ transduction[101].

Electric eels and other electric fishes exemplify the large-scale conversion of ionic energy into electrical discharge[102]. In Electrophorus electricus, thousands of electrocytes are stacked in series, each acting as an ion-driven capacitor. The posterior membrane is rich in voltage-gated Na+ channels, while the anterior face contains mainly K+ channels, creating directional ionic flow during activation [Figure 5C]. At rest, opposing transmembrane potentials across the anterior and posterior faces largely cancel, whereas during an impulse the posterior membrane depolarises, yielding an effective transcellular potential of roughly 150 mV per electrocyte; stacking thousands in series produces open-circuit voltages exceeding 600 V and, with parallel columns, peak currents approaching the ampere scale[103]. Near-synchronous activation along the organ is achieved by tailored conduction delays from the command nucleus, ensuring that virtually all electrocytes fire within the ~ 2 ms discharge window. Neural activation triggers this process almost simultaneously across the organ, converting electrochemical gradients into brief yet powerful electric pulses that enable predation and sensing[18].

Beyond individual organisms, certain species of weakly electric fish engage in collective electrosensory behavior[104]. Recent modeling, neural recordings, and behavioral tests demonstrate that conspecific electric organ discharges (EODs) provide additional ‘cons-images’ on a receiver’s skin that extend electrolocation beyond the range achievable by self-EODs, effectively creating a shared sensory field. Because cons-images traverse shorter paths to the sensing surface and are funnelled by the nearby fish’s body, their decay with distance is shallower than self-images, yielding range extension without requiring explicit knowledge of conspecific position; moreover, the peak location and width of cons-images closely match self-image cues, supporting object localization and discrimination[20].

At the microbial level, conductive nanowires and electroactive biofilms exhibit collective electrical behavior. In communities of Shewanella oneidensis and related species, cells produce cytochrome-rich nanowires that interconnect neighboring cells and create extended conductive networks[97] [Figure 5D]. These networks enable long-range ion transport and electron flow between cells and distant mineral surfaces, allowing the entire biofilm to function as a coherent electrochemical system[105,106]. Within the same collective context, Bacillus subtilis biofilms propagate potassium-mediated electrical waves that synchronise metabolism and membrane potential across millimeter scales. Cells experiencing nutrient stress release K+ through the potassium efflux channel (YugO channel), generating depolarisation fronts that coordinate growth and resource use within the community[107]. Together, these mechanisms reveal how microbial populations integrate ionic and electronic signaling to achieve communication, forming living networks that operate collectively rather than as isolated cells.

Among animals, migratory birds provide one of the most compelling examples of collective sensing. The navigational mechanism is likely to rely on the quantum spin dynamics of photoinduced radical pairs in the cryptochrome flavoproteins of bird retinas[108,109]. The process concerns the ionic responses of magnetosensitive proteins. In the night-migratory European robin, the cryptochrome 4 (CRY4) protein shows intrinsic magnetic sensitivity[110]. Moreover, under identical in vitro measurement conditions, its magnetic sensitivity surpasses that of CRY4 proteins from non-migratory pigeons and chickens. This ionic magnetoreception exemplifies how quantum processes can shape coordinated behavior across populations.

BIOINSPIRED IONTRONIC APPLICATIONS

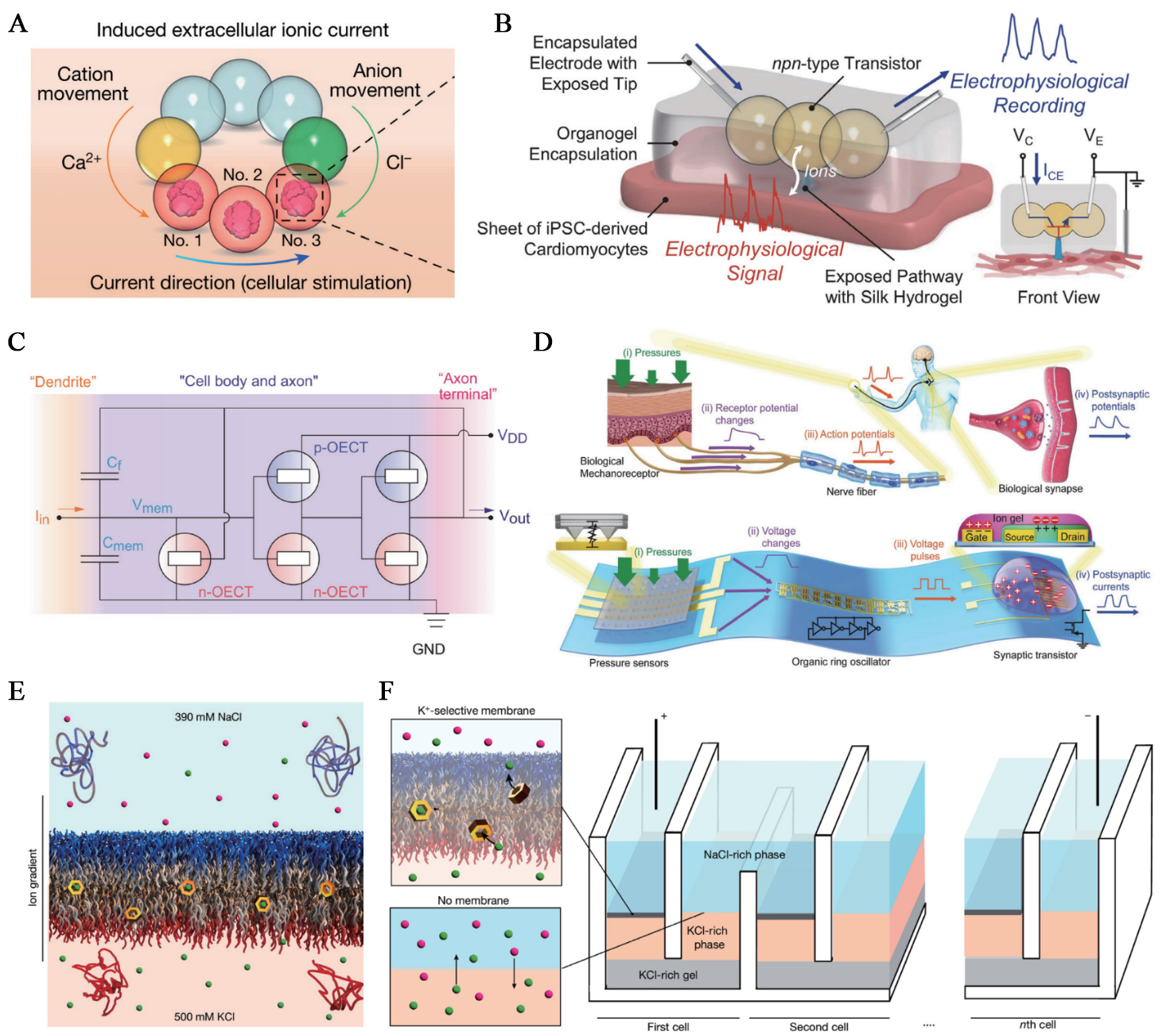

Drawing on the controlled ion transport strategies described in Section 2, bioinspired iontronics seeks to recapitulate these motifs in artificial architectures. By mimicking biological principles (bionic design), iontronic systems can be engineered to perform key functions, including power supply, sensing, signal processing, and biointerface control, which we detail in this section [Table 3 and Figure 6].

Figure 6. Bioinspired bioiontronics. (A) Dropletronic power source for the modulation of neuronal activities. This figure is quoted with permission from Zhang et al.[27]; (B) Organogel-encapsulated npn-type dropletronic transistor interfaced with living cardiac tissue for ionic signal recording. This figure is quoted with permission from Zhang et al.[29]; (C) The OECN based on Axon Hillock circuit. This figure is quoted with permission from Harikesh et al.[111]; (D) Bioinspired artificial afferent nerve: top, biological tactile pathway with mechanoreceptors, spike initiation, and synaptic relay; bottom, flexible organic counterpart integrating pressure-sensor arrays, an organic ring oscillator that encodes pressure into spike frequency, and a synaptic transistor that sums inputs. This figure is quoted with permission from Kim et al.[112]; (E) Valinomycin-doped block-copolymer bilayer shuttles K⁺ across the membrane under a NaCl/KCl gradient, producing an ionic output power. This figure is quoted with permission from Sproncken et al.[113]; (F) A bioinspired power unit comprising serial stacks of ion-selective membranes and conductive bridges; each cell contributes an incremental potential, so total voltage scales with the number of cells. This figure is quoted with permission from Sproncken et al.[113]. VC: Collector voltage; VE: emitter voltage; ICE: collector-emitter anion transport; OECT: organic electrochemical transistor; VDD: drain voltage; OECN: organic electrochemical neuron.

Biological models and their corresponding iontronic principles and implementations

| Biological model | Key principle | Bioinspired iontronics |

| Electrocytes | Stacked ion-selective layers that convert ionic gradients into ionic outputs | Dropletronic ionic power sources[27] |

| Redox metabolism | Redox-driven proton and electron coupling that generates sustained electrochemical gradients | Enzyme-enabled droplet biobatteries[34] |

| Synaptic connection | Voltage-dependent, reversible alteration of ionic conductivity that underlies short-term/long-term plasticity | Dropletronic memristors[29] |

| Neuronal electrophysiology | Membrane depolarisation driven by ion accumulation | Organic electrochemical transistors[111] |

Direct ionic current stimulation synergises with the tissue’s intrinsic charge carriers, conferring unique advantages for bioiontronic batteries[114]. Microscale soft ionic power sources take inspiration from the electric eel’s stacked electrocytes, which convert internal ion gradients into voltage. They arrange nanoliter hydrogel droplets (termed dropletronics) to pattern salt gradients and ion-selective pathways that, once triggered, sustain diffusive ionic currents for electrode-free neuromodulation. The droplet networks operate as compartmentalized structures linked by droplet interface bilayers, resembling how stacked electrocytes regulate ion flux through selectively permeable membranes. This correspondence underscores how droplet-based architectures recapitulate the essential ion-gradient-driven mechanism underlying electrogenic biological systems. In a droplet network layout, a high-salinity reservoir couples through cation- and anion-selective droplets to a target droplet containing neural microtissues or brain slices, driving ionic current to modulate neuronal network activities[27] [Figure 6A]. Another application, inspired by cellular redox metabolism, employs enzyme-enabled droplet biobatteries. These devices couple NADH oxidation to O2 reduction across droplet-interface bilayers via redox mediators and cation-selective pathways to deliver hours-long, steady ionic currents that drive ion migration and directional chemical signaling in synthetic tissues[34].

Moving forward, the control of ionic outputs requires bioiontronic circuitry components. Early ion-channel-doped biomembranes showed that reversible, voltage-driven insertion of peptide pores into a lipid bilayer produces memristive switching with synapse-like facilitation/depression and short retention[115]. The development of a set of freestanding, microscale, soft dropletronic modules, through surfactant-supported hydrogel droplet assembly, has further addressed the need for bioiontronic circuits[29] [Figure 6B]. Hydrogel modifications provided cation- and anion-selective hydrogels as ionic analogues of p- and n-type semiconductors. By configuring droplet combinations, dropletronic diodes, transistors, various reconfigurable logic gates, and synthetic synapses with ionic memory effects have been developed. Further, a dropletronic device can interface with living heart cells and record the ionic signals from their coordinated beating. The variety and scope of dropletronics will contribute to tissue engineering and organ repair, as cells can be incorporated into droplets to form hybrid constructs[116,117]. More recently, dropletronic devices further exhibited paired-pulse plasticity, spike-rate dependence, Hebbian/associative learning, and performed reservoir-computing tasks at pico- to nanowatt power[118].

Dropletronic devices still face challenges in bioiontronic applications. Coalescence, evaporation, and shape instability of synthetic droplets could disrupt ionic pathways and compromise circuit reproducibility. Addressing these issues will require advances in droplet stabilisation strategies, including robust surfactant and lipid formulations, osmotic balancing, humidity-controlled or oil-immersed environments, and microstructured or polymer-coated encapsulations that eliminate coalescence and evaporation. Looking ahead, extending dropletronics beyond planar or linear networks toward hierarchically organised three-dimensional architectures would more closely mimic the multiscale organisation of tissues. In such three-dimensional assemblies, droplets of different sizes and functions could interact across multiple hierarchical levels, similar to how cellular microdomains are organised within tissues, enabling integrated sensing-processing-actuation pathways or multiscale ionic computation that are inaccessible in two-dimensional configurations.

Bioinspired bioiontronic interfaces can also transduce mechanical inputs into spikes and synaptic currents while remaining biocompatible with living tissue[119,120]. Organic electrochemical neurons (OECNs) constructed based on all-printed complementary organic electrochemical transistors (OECTs) exhibit diverse neuronal characteristics. Similar to neuronal mechanisms, integrating injected currents into input terminals generates spike signals within OECN circuits [Figure 6C]. Printed OECNs can be tuned in frequency by changing electrolyte composition, and they have been interfaced with living tissues to demonstrate direct ionic coupling[111]. In parallel, an artificial afferent nerve integrates three modules: resistive pressure sensors, an organic ring oscillator that converts pressure into spike frequency, and a synaptic transistor that aggregates multichannel inputs into postsynaptic currents [Figure 6D]. This architecture supports tactile feature fusion and Braille discrimination. It also establishes a hybrid reflex arc that can actuate muscles[112]. Together, these platforms demonstrate how ion-coupled hardware realizes the biological flow from sensation to synaptic integration, with applications in prosthetics and robotics.

Large-area, self-healing ion-selective membranes extend iontronics to macroscale energy conversion. Using an aqueous two-phase system as a soft template, molecularly thin block-copolymer bilayers form over centimeter areas and self-repair while maintaining high ionic resistance[113]. Doping with the K+ carrier valinomycin confers strong K+ selectivity, so an ion concentration gradient is transduced into a stable ionic output [Figure 6E]. Tandem stacking of selective and non-selective interfaces enables compact modular units to generate cumulative ionic outputs [Figure 6F], allowing the development of macroscopic, scalable ionic power sources.

CONCLUSION AND OUTLOOK

Natural ionic processes provide archetypes and grant germane inspirations for bioiontronics. The Review summarizes the bioinspiration across various biological scales for the development of bioiontronic devices. Future breakthroughs may happen at biointerfaces, as bioiontronics often employs soft, biocompatible materials and uses ions as carriers for information transfer[121-123]. Applications may occur at the skin and intestinal interfaces, where physiological ions such as K+, Na+, Ca2+, and Cl- are exchanged to enable activity recording and modulation[122,124-126]. Guided tissue repair and regeneration may use mild ion gradients to coordinate cell migration, promote wound healing, and support tissue integrity[127-131].

The ionic mechanisms found in biology may also benefit the development of human-computer interfaces[132-134] and neuromorphic systems[111,135-140]. Bioiontronic neurons may couple with living tissues, enabling spike-based, event-driven sensing and interaction[141-143]. Applications include adaptive therapeutics and soft robotics. Moreover, the electrogenic phenomena observed in fish species and bacteria offer insights for self-powered devices[144-147], such as bioiontronic batteries and fuel cells. Collective electro-sensing phenomena in the biological realm also provide biomimetic models for developing information transmission and navigation systems[148].

Challenges exist in two directions. First, the performance and stability of bioiontronic systems must be improved to ensure that they are not merely gimmicks used by experts in academic laboratories. Regarding energy supply, harnessing endogenous resources in biological environments, such as glucose, may provide a long-term energy solution for bioiontronic implants. For ion selection and ionic rectification, the performance of many synthetic systems is still inferior to that of their natural counterparts. For system integration, few biomimetic devices have truly integrated multiple functions, such as sensing, information processing, and actuation. Such integration becomes essential in applications that require closed-loop operation, where rapid sensing, in situ processing, and timely actuation must occur within a continuous feedback cycle. For example, an implantable bioiontronic platform that monitors biochemical or ionic fluctuations and autonomously delivers a corrective stimulus would rely critically on this closed-loop capability to maintain local physiological balance. However, the establishment of complex computational and feedback mechanisms remains under exploration. In addition, practical deployment will require attention to several material and chemical parameters at the biointerface. Ionic environments in vivo exhibit variations in pH, ionic concentration, protein content, and enzymatic activity, all of which can alter the stability and performance of organic, polymeric, or mixed ionic-electronic materials. Minimising chemical mismatches, such as swelling, ion depletion, hydrolysis, or protein-induced fouling, will be essential for maintaining device fidelity over time. Ensuring compatibility with established biocompatibility standards, including ISO 10993 guidelines for cytotoxicity, sensitisation, irritation, and long-term implantation, will further guide material selection and surface engineering strategies. Moreover, as bioiontronic systems increasingly interface with living tissues, the field will benefit from the establishment of specific quality parameters to evaluate device performance and stability under physiological conditions. Relevant quality parameters include ionic conductivity stability, transconductance retention, hysteresis, leakage current, impedance drift, mechanical fatigue resistance, and long-term ion-electron transduction fidelity, which together provide quantitative benchmarks for assessing robustness and ensuring reproducible operation in biologically relevant environments[149-151]. Finally, many underpinning ionic mechanisms of natural phenomena remain elusive. The unravelling of nature’s mysteries is likely to continue as new bioiontronic theories and approaches are further developed. Overcoming these challenges will involve a multipronged approach, with bioiontronic technologies filling a valuable niche.

DECLARATIONS

Authors’ contributions

Conceived the idea: Lyu, Y.; Su, Y.; Zhang, Y.

All authors participated in the writing and revision of the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Financial support and sponsorship

This work was supported by a Starting Grant from the École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne (EPFL; Zhang, Y.), the EPFL Excellence in Engineering (E3) Program (Lyu, Y.), and the Swiss National Science Foundation (grant numbers 10005601 and 10005936; Zhang, Y.).

Conflicts of interest

Zhang, Y. is an Editorial Board Member of the journal Iontronics. Zhang, Y. was not involved in any steps of the editorial process, including reviewer selection, manuscript handling, or decision-making. The other authors declared that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026.

REFERENCES

1. Wan, C.; Xiao, K.; Angelin, A.; Antonietti, M.; Chen, X. The rise of bioinspired ionotronics. Adv. Intell. Syst. 2019, 1, 1900073.

2. Wu, B.; Yan, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Ji, C.; Lin, Y.; Lang, C. Ions in motion: From biological channels to engineered transport systems. Giant 2025, 22, 100352.

3. Transport Across Natural and Modified Biological Membranes and its Implications in Physiology and Therapy; Kulbacka, J., Satkauskas, S., Eds.; Advances in Anatomy, Embryology and Cell Biology, Vol. 227; Springer International Publishing, 2017.

4. Funk, R. H. W.; Scholkmann, F. The significance of bioelectricity on all levels of organization of an organism. Part 1: from the subcellular level to cells. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 2023, 177, 185-201.

5. Levin, M. Large-scale biophysics: ion flows and regeneration. Trends. Cell. Biol. 2007, 17, 261-70.

6. Levin, M. Bioelectric networks: the cognitive glue enabling evolutionary scaling from physiology to mind. Anim. Cogn. 2023, 26, 1865-91.

7. Sahasrabudhe, A.; Cea, C.; Anikeeva, P. Multifunctional bioelectronics for brain-body circuits. Nat. Rev. Bioeng. 2025, 3, 465-84.

8. Dai, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Yu, W.; et al. Biomolecular condensates regulate cellular electrochemical equilibria. Cell 2024, 187, 5951-5966.e18.

9. Trinh, M. D. L.; Masuda, S. Chloroplast pH homeostasis for the regulation of photosynthesis. Front. Plant. Sci. 2022, 13, 919896.

10. Lyu, H.; Lazár, D. Effect of ion fluxes on regulating the light-induced transthylakoid electric potential difference. Plant. Physiol. Biochem. 2023, 194, 60-9.

11. Chan, D. C. Mitochondria: dynamic organelles in disease, aging, and development. Cell 2006, 125, 1241-52.

12. Vyssokikh, M. Y.; Holtze, S.; Averina, O. A.; et al. Mild depolarization of the inner mitochondrial membrane is a crucial component of an anti-aging program. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2020, 117, 6491-501.

13. Baumann, N.; Pham-Dinh, D. Biology of oligodendrocyte and myelin in the mammalian central nervous system. Physiol. Rev. 2001, 81, 871-927.

14. Bazargani, N.; Attwell, D. Astrocyte calcium signaling: the third wave. Nat. Neurosci. 2016, 19, 182-9.

16. Hagihara, T.; Mano, H.; Miura, T.; Hasebe, M.; Toyota, M. Calcium-mediated rapid movements defend against herbivorous insects in Mimosa pudica. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 6412.

17. Jia, N.; Yang, J.; Liu, J.; Zhang, J. Electric field: a key signal in wound healing. Chin. J. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2021, 3, 95-102.

18. Schroeder, T. B. H.; Guha, A.; Lamoureux, A.; et al. An electric-eel-inspired soft power source from stacked hydrogels. Nature 2017, 552, 214-8.

19. de Santana, C. D.; Crampton, W. G. R.; Dillman, C. B.; et al. Unexpected species diversity in electric eels with a description of the strongest living bioelectricity generator. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 4000.

21. Nadell, C. D.; Xavier, J. B.; Foster, K. R. The sociobiology of biofilms. FEMS. Microbiol. Rev. 2009, 33, 206-24.

22. Malvankar, N. S.; Vargas, M.; Nevin, K. P.; et al. Tunable metallic-like conductivity in microbial nanowire networks. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2011, 6, 573-9.

23. Xiao, T.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, Y.; Yan, Y. Iontronic components: From liquid- to solid-states. Nano. Res. 2023, 16, 13343-57.

24. Ro, Y. G.; Na, S.; Kim, J.; et al. Iontronics: neuromorphic sensing and energy harvesting. ACS. Nano. 2025, 19, 24425-507.

25. Chen, X.; Xia, X.; Guo, C. F. Flexible iontronic sensing: ionic materials, electrodes, and encapsulation. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, 36, e12920.

26. Xiao, K.; Wan, C.; Jiang, L.; Chen, X.; Antonietti, M. Bioinspired ionic sensory systems: the successor of electronics. Adv. Mater. 2020, 32, e2000218.

27. Zhang, Y.; Riexinger, J.; Yang, X.; et al. A microscale soft ionic power source modulates neuronal network activity. Nature 2023, 620, 1001-6.

28. Zhang, Y.; Sun, T.; Yang, X.; et al. A microscale soft lithium-ion battery for tissue stimulation. Nat. Chem. Eng. 2024, 1, 691-701.

29. Zhang, Y.; Tan, C. M. J.; Toepfer, C. N.; Lu, X.; Bayley, H. Microscale droplet assembly enables biocompatible multifunctional modular iontronics. Science 2024, 386, 1024-30.

30. Maraj, J. J.; Najem, J. S.; Ringley, J. D.; Weiss, R. J.; Rose, G. S.; Sarles, S. A. Short-term facilitation-then-depression enables adaptive processing of sensory inputs by ion channels in biomolecular synapses. ACS. Appl. Electron. Mater. 2021, 3, 4448-58.

31. Mansour, M. M.; Maraj, J. J.; Pyron, R. J.; Barrera, F. N.; Sarles, S. A. Biomolecular neuristors from functionalized lipid membranes. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2409296.

32. Segars, B.; Rosenberg, K.; Shrestha, S.; Maraj, J. J.; Sarles, S. A.; Freeman, E. Neuron-inspired biomolecular memcapacitors formed using droplet interface bilayer networks. Adv. Elect. Mater. 2025, 11, 2400644.

33. Luo, J.; Remy, A.; Zhang, Y. Iontronic devices from biological nanopores to artificial systems: emerging applications and future perspectives. Chem. Rev. 2025, 125, 11840-77.

34. Liu, J.; Qing, Y.; Zhou, L.; et al. Enzyme-enabled droplet biobattery for powering synthetic tissues. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2024, 63, e202408665.

35. Morth, J. P.; Pedersen, B. P.; Buch-Pedersen, M. J.; et al. A structural overview of the plasma membrane Na+ ,K+-ATPase and H+-ATPase ion pumps. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2011, 12, 60-70.

36. Galera-Laporta, L.; Comerci, C. J.; Garcia-Ojalvo, J.; Süel, G. M. IonoBiology: the functional dynamics of the intracellular metallome, with lessons from bacteria. Cell. Syst. 2021, 12, 497-508.

37. Choi, S.; Lee, J. M.; Kim, K. K. Biomolecular condensates: molecular structure, biological functions, diseases, and therapeutic targets. Mol. Biomed. 2025, 6, 99.

38. Middleton, P.; Vergis, N. Mitochondrial dysfunction and liver disease: role, relevance, and potential for therapeutic modulation. Therap. Adv. Gastroenterol. 2021, 14, 17562848211031394.

39. Stoffel, F.; Papp, M.; Gil-Garcia, M.; et al. Enhancement of enzymatic activity by biomolecular condensates through pH buffering. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 6368.

40. Dai, Y.; Chamberlayne, C. F.; Messina, M. S.; et al. Interface of biomolecular condensates modulates redox reactions. Chem 2023, 9, 1594-609.

41. Zhu, L.; Pan, Y.; Hua, Z.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, X. Ionic effect on the microenvironment of biomolecular condensates. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2024, 146, 14307-17.

42. Banani, S. F.; Lee, H. O.; Hyman, A. A.; Rosen, M. K. Biomolecular condensates: organizers of cellular biochemistry. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2017, 18, 285-98.

43. Chen, K.; Cao, X. Biomolecular condensates: phasing in regulated host-pathogen interactions. Trends. Immunol. 2025, 46, 29-45.

44. Finazzi, G.; Petroutsos, D.; Tomizioli, M.; et al. Ions channels/transporters and chloroplast regulation. Cell. Calcium. 2015, 58, 86-97.

45. Armbruster, U.; Correa Galvis, V.; Kunz, H. H.; Strand, D. D. The regulation of the chloroplast proton motive force plays a key role for photosynthesis in fluctuating light. Curr. Opin. Plant. Biol. 2017, 37, 56-62.

46. Li, M.; Svoboda, V.; Davis, G.; Kramer, D.; Kunz, H. H.; Kirchhoff, H. Impact of ion fluxes across thylakoid membranes on photosynthetic electron transport and photoprotection. Nat. Plants. 2021, 7, 979-88.

47. Zhang, S.; Zou, B.; Cao, P.; et al. Structural insights into photosynthetic cyclic electron transport. Mol. Plant. 2023, 16, 187-205.

48. Pottosin, I.; Shabala, S. Transport across chloroplast membranes: optimizing photosynthesis for adverse environmental conditions. Mol. Plant. 2016, 9, 356-70.

49. Johnson, M. P. Structure, regulation and assembly of the photosynthetic electron transport chain. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2025, 26, 667-90.

50. Vercellino, I.; Sazanov, L. A. The assembly, regulation and function of the mitochondrial respiratory chain. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2022, 23, 141-61.

51. Fan, M.; Zhang, J.; Tsai, C. W.; et al. Structure and mechanism of the mitochondrial Ca2+ uniporter holocomplex. Nature 2020, 582, 129-33.

52. Chen, B.; Lyssiotis, C. A.; Shah, Y. M. Mitochondria-organelle crosstalk in establishing compartmentalized metabolic homeostasis. Mol. Cell. 2025, 85, 1487-508.

53. Coupland, C. E.; Karimi, R.; Bueler, S. A.; et al. High-resolution electron cryomicroscopy of V-ATPase in native synaptic vesicles. Science 2024, 385, 168-74.

54. Verweij, W.; Spelt, C.; Di Sansebastiano, G. P.; et al. An H+ P-ATPase on the tonoplast determines vacuolar pH and flower colour. Nat. Cell. Biol. 2008, 10, 1456-62.

55. Li, Y.; Zeng, H.; Xu, F.; Yan, F.; Xu, W. H+-ATPases in plant growth and stress responses. Annu. Rev. Plant. Biol. 2022, 73, 495-521.

56. Schofield, Z.; Meloni, G. N.; Tran, P.; et al. Bioelectrical understanding and engineering of cell biology. J. R. Soc. Interface. 2020, 17, 20200013.

57. Chen, S.; Zhang, T.; Tappertzhofen, S.; Yang, Y.; Valov, I. Electrochemical-memristor-based artificial neurons and synapses-fundamentals, applications, and challenges. Adv. Mater. 2023, 35, e2301924.

58. Kuznetsov, A. V.; Javadov, S.; Grimm, M.; Margreiter, R.; Ausserlechner, M. J.; Hagenbuchner, J. Crosstalk between mitochondria and cytoskeleton in cardiac cells. Cells 2020, 9.

59. Bean, B. P. The action potential in mammalian central neurons. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2007, 8, 451-65.

61. Raghavan, M.; Fee, D.; Barkhaus, P. E. Generation and propagation of the action potential; Handbook of Clinical Neurology, Vol. 160; Elsevier, 2019; pp. 3-22.

62. Guo, Y. M.; Ong, C. K. Possible mechanism of action potential propagation mediated by static electric field: a novel assumption of understanding nerve interaction and ephaptic coupling. Heliyon 2024, 10, e37637.

63. Schmidt, H.; Knösche, T. R. Action potential propagation and synchronisation in myelinated axons. PLoS. Comput. Biol. 2019, 15, e1007004.

64. Pásek, M.; Simurda, J.; Christé, G.; Orchard, C. H. Modelling the cardiac transverse-axial tubular system. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 2008, 96, 226-43.

65. Gilbert, G.; Demydenko, K.; Dries, E.; et al. Calcium signaling in cardiomyocyte function. Cold. Spring. Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2020, 12, a035428.

66. Huang, C. L.; Lei, M. Cardiomyocyte electrophysiology and its modulation: current views and future prospects. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B. Biol. Sci. 2023, 378, 20220160.

67. Liu, J.; Laksman, Z.; Backx, P. H. The electrophysiological development of cardiomyocytes. Adv. Drug. Delivery. Rev. 2016, 96, 253-73.

68. Stoppel, W. L.; Kaplan, D. L. Black LD, 3. R. D. Electrical and mechanical stimulation of cardiac cells and tissue constructs. Adv. Drug. Delivery. Rev. 2016, 96, 135-55.

69. Rorsman, P.; Ashcroft, F. M. Pancreatic β-cell electrical activity and insulin secretion: of mice and men. Physiol. Rev. 2018, 98, 117-214.

70. Gao, Y. Biology of Vascular Smooth Muscle: Vasoconstriction and Dilatation; Springer Nature Singapore, 2022.

71. Hansali, S.; Pio-lopez, L.; Lapalme, J. V.; Levin, M. The role of bioelectrical patterns in regulative morphogenesis: an evolutionary simulation and validation in planarian regeneration. IEEE. Trans. Mol. Biol. Multi-Scale. Commun. 2025, 11, 305-31.

72. Durant, F.; Morokuma, J.; Fields, C.; Williams, K.; Adams, D. S.; Levin, M. Long-term, stochastic editing of regenerative anatomy via targeting endogenous bioelectric gradients. Biophys. J. 2017, 112, 2231-43.

73. Chernet, B. T.; Levin, M. Transmembrane voltage potential is an essential cellular parameter for the detection and control of tumor development in a Xenopus model. Dis. Model. Mech. 2013, 6, 595-607.

74. Mousavi, S. A.; Chauvin, A.; Pascaud, F.; Kellenberger, S.; Farmer, E. E. GLUTAMATE RECEPTOR-LIKE genes mediate leaf-to-leaf wound signalling. Nature 2013, 500, 422-6.

75. Toyota, M.; Spencer, D.; Sawai-Toyota, S.; et al. Glutamate triggers long-distance, calcium-based plant defense signaling. Science 2018, 361, 1112-5.

76. Wudick, M. M.; Portes, M. T.; Michard, E.; et al. CORNICHON sorting and regulation of GLR channels underlie pollen tube Ca2+ homeostasis. Science 2018, 360, 533-6.

77. Tian, W.; Wang, C.; Gao, Q.; Li, L.; Luan, S. Calcium spikes, waves and oscillations in plant development and biotic interactions. Nat. Plants. 2020, 6, 750-9.

78. Bellandi, A.; Papp, D.; Breakspear, A.; et al. Diffusion and bulk flow of amino acids mediate calcium waves in plants. Sci. Adv. 2022, 8, eabo6693.

79. Yan, C.; Gao, Q.; Yang, M.; et al. Ca2+/calmodulin-mediated desensitization of glutamate receptors shapes plant systemic wound signalling and anti-herbivore defence. Nat. Plants. 2024, 10, 145-60.

80. Lin, J.; Guan, Q.; Feng, J.; et al. Interactions between active matters and endogenous fields. Adv. Mater. 2025, 37, e03091.

81. Zhao, M.; Song, B.; Pu, J.; et al. Electrical signals control wound healing through phosphatidylinositol-3-OH kinase-gamma and PTEN. Nature 2006, 442, 457-60.

82. Leal, J.; Shaner, S.; Jedrusik, N.; Savelyeva, A.; Asplund, M. Electrotaxis evokes directional separation of co-cultured keratinocytes and fibroblasts. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 11444.

83. Shim, G.; Breinyn, I. B.; Martínez-Calvo, A.; Rao, S.; Cohen, D. J. Bioelectric stimulation controls tissue shape and size. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 2938.

84. Yu, S. M.; Granick, S. Electric spiking activity in epithelial cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2025, 122, e2427123122.

85. Saw, T. B.; Gao, X.; Li, M.; et al. Transepithelial potential difference governs epithelial homeostasis by electromechanics. Nat. Phys. 2022, 18, 1122-8.

86. Cervera, J.; Manzanares, J. A.; Levin, M.; Mafe, S. Oscillatory phenomena in electrophysiological networks: the coupling between cell bioelectricity and transcription. Comput. Biol. Med. 2024, 180, 108964.

87. Ferreira, F.; Moreira, S.; Zhao, M.; Barriga, E. H. Stretch-induced endogenous electric fields drive directed collective cell migration in vivo. Nat. Mater. 2025, 24, 462-70.

88. Harris, M. P. Bioelectric signaling as a unique regulator of development and regeneration. Development 2021, 148, dev180794.

89. Levin, M. Bioelectric signaling: reprogrammable circuits underlying embryogenesis, regeneration, and cancer. Cell 2021, 184, 1971-89.

90. Levin, M. Bioelectric mechanisms in regeneration: Unique aspects and future perspectives. Semin. Cell. Dev. Biol. 2009, 20, 543-56.

91. Cervera, J.; Pai, V. P.; Levin, M.; Mafe, S. From non-excitable single-cell to multicellular bioelectrical states supported by ion channels and gap junction proteins: Electrical potentials as distributed controllers. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 2019, 149, 39-53.

92. Levin, M.; Selberg, J.; Rolandi, M. Endogenous bioelectrics in development, cancer, and regeneration: drugs and bioelectronic devices as electroceuticals for regenerative medicine. iScience 2019, 22, 519-33.

93. Pio-Lopez, L.; Levin, M. Morphoceuticals: perspectives for discovery of drugs targeting anatomical control mechanisms in regenerative medicine, cancer and aging. Drug. Discov. Today. 2023, 28, 103585.

94. Kofman, K.; Levin, M. Bioelectric pharmacology of cancer: a systematic review of ion channel drugs affecting the cancer phenotype. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 2024, 191, 25-39.

95. Shook, E. N.; Barlow, G. T.; Garcia-Rosales, D.; Gibbons, C. J.; Montague, T. G. Dynamic skin behaviors in cephalopods. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2024, 86, 102876.

96. Yu, Y.; Zhu, X.; Jiang, S.; et al. Cephalopods’ skin-inspired design of nanoscale electronic transport layers for adaptive electrochromic tuning. Adv. Sci. (Weinh). 2024, 11, e2405444.

97. Gorby, Y. A.; Yanina, S.; McLean, J. S.; et al. Electrically conductive bacterial nanowires produced by Shewanella oneidensis strain MR-1 and other microorganisms. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2006, 103, 11358-63.

98. Zhang, Y.; Tao, T. H. A bioinspired wireless epidermal photoreceptor for artificial skin vision. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2020, 30, 2000381.

100. Zylinski, S.; Johnsen, S. Mesopelagic cephalopods switch between transparency and pigmentation to optimize camouflage in the deep. Curr. Biol. 2011, 21, 1937-41.

101. Shi, H.; Wu, S.; Si, M.; et al. Cephalopod-inspired design of photomechanically modulated display systems for on-demand fluorescent patterning. Adv. Mater. 2022, 34, e2107452.

102. Xu, J.; Cui, X.; Zhang, H. The third form electric organ discharge of electric eels. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 6193.

103. He, P.; Yue, J.; Qiu, Z.; Meng, Z.; He, J.; Li, D. Consecutive multimaterial printing of biomimetic ionic hydrogel power sources with high flexibility and stretchability. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 5261.

104. Worm, M.; Landgraf, T.; Prume, J.; Nguyen, H.; Kirschbaum, F.; von der Emde, G. Evidence for mutual allocation of social attention through interactive signaling in a mormyrid weakly electric fish. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2018, 115, 6852-7.

105. Liu, X.; Ueki, T.; Gao, H.; et al. Microbial biofilms for electricity generation from water evaporation and power to wearables. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 4369.

106. Guberman-Pfeffer, M. J.; Dorval Courchesne, N.; Lovley, D. R. Microbial nanowires for sustainable electronics. Nat. Rev. Bioeng. 2024, 2, 869-86.

107. Prindle, A.; Liu, J.; Asally, M.; Ly, S.; Garcia-Ojalvo, J.; Süel, G. M. Ion channels enable electrical communication in bacterial communities. Nature 2015, 527, 59-63.

108. Ritz, T.; Thalau, P.; Phillips, J. B.; Wiltschko, R.; Wiltschko, W. Resonance effects indicate a radical-pair mechanism for avian magnetic compass. Nature 2004, 429, 177-80.

109. Engels, S.; Schneider, N. L.; Lefeldt, N.; et al. Anthropogenic electromagnetic noise disrupts magnetic compass orientation in a migratory bird. Nature 2014, 509, 353-6.

110. Xu, J.; Jarocha, L. E.; Zollitsch, T.; et al. Magnetic sensitivity of cryptochrome 4 from a migratory songbird. Nature 2021, 594, 535-40.

111. Harikesh, P. C.; Yang, C. Y.; Tu, D.; et al. Organic electrochemical neurons and synapses with ion mediated spiking. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 901.

112. Kim, Y.; Chortos, A.; Xu, W.; et al. A bioinspired flexible organic artificial afferent nerve. Science 2018, 360, 998-1003.

113. Sproncken, C. C. M.; Liu, P.; Monney, J.; et al. Large-area, self-healing block copolymer membranes for energy conversion. Nature 2024, 630, 866-71.

114. Wang, C.; Fu, K. K.; Dai, J.; et al. Inverted battery design as ion generator for interfacing with biosystems. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 15609.

115. Najem, J. S.; Taylor, G. J.; Weiss, R. J.; et al. Memristive ion channel-doped biomembranes as synaptic mimics. ACS. Nano. 2018, 12, 4702-11.

116. Jin, Y.; Mikhailova, E.; Lei, M.; et al. Integration of 3D-printed cerebral cortical tissue into an ex vivo lesioned brain slice. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 5986.

117. Yang, X.; Artibani, M.; Jin, Y.; et al. 3D microtumors representing ovarian cancer minimal residual disease respond to the fatty acid oxidation inhibitor perhexiline. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2025, 14, e2404072.

118. Li, Z.; Myers, S. K.; Xiao, J.; et al. Neuromorphic ionic computing in droplet interface synapses. Sci. Adv. 2025, 11, eadv6603.

120. Peng, P.; Qian, H.; Liu, J.; Wang, Z.; Wei, D. Bioinspired ionic control for energy and information flow. Int. J. Smart. Nano. Mater. 2024, 15, 198-221.

121. Chang, Y.; Wang, L.; Li, R.; et al. First decade of interfacial iontronic sensing: from droplet sensors to artificial skins. Adv. Mater. 2021, 33, e2003464.

122. Yang, X.; Tsai, C.; Yang, Y.; et al. Nano-bio interfaces for electrical and biochemical signal transduction. Nat. Rev. Bioeng. 2025, 374.

123. Shi, J.; Li, P.; Kim, S.; Tian, B. Implantable bioelectronic devices for photoelectrochemical and electrochemical modulation of cells and tissues. Nat. Rev. Bioeng. 2025, 3, 485-504.

124. Chen, W.; Zhai, L.; Zhang, S.; et al. Cascade-heterogated biphasic gel iontronics for electronic-to-multi-ionic signal transmission. Science 2023, 382, 559-65.

125. Li, X. H.; Hu, N.; Chang, Z. H.; et al. Brain organoid maturation and implantation integration based on electrical signals input. J. Adv. Res. 2025, 73, 375-95.

126. Yan, T.; Liu, J. Transmembrane ion channels: from natural to artificial systems. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2025, 64, e202416200.

127. Liu, M.; Tao, T. H.; Zhang, Y. Silk materials light up the green society. Adv. Energy. Sustain. Res. 2021, 2, 2100035.

128. Liu, M.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, K.; et al. Biomimicking antibacterial opto-electro sensing sutures made of regenerated silk proteins. Adv. Mater. 2021, 33, e2004733.

129. Zhang, Y.; Chen, X.; Chen, D.; et al. Partially metal-coated tips for near-field nanospectroscopy. Phys. Rev. Applied. 2021, 15, 014048.

130. Deng, K.; Luo, R.; Chen, Y.; et al. Electrical stimulation therapy - dedicated to the perfect plastic repair. Adv. Sci. (Weinh). 2025, 12, e2409884.

131. Liu, Y.; Bai, Y.; Heng, B. C.; et al. Biomimetic electroactive materials and devices for regenerative engineering. Nat. Rev. Electr. Eng. 2025, 2, 188-204.

132. Liu, M.; Zhang, Y.; Tao, T. H. Recent progress in bio-integrated intelligent sensing system. Adv. Intell. Syst. 2022, 4, 2100280.

133. Liu, M.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, J.; et al. A star-nose-like tactile-olfactory bionic sensing array for robust object recognition in non-visual environments. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 79.

134. Liu, M.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Qin, N.; Tao, T. H. Robotic manipulation under harsh conditions using self-healing silk-based iontronics. Adv. Sci. (Weinh). 2022, 9, e2102596.

135. Keene, S. T.; Lubrano, C.; Kazemzadeh, S.; et al. A biohybrid synapse with neurotransmitter-mediated plasticity. Nat. Mater. 2020, 19, 969-73.

136. John, R. A.; Tiwari, N.; Patdillah, M. I. B.; et al. Self healable neuromorphic memtransistor elements for decentralized sensory signal processing in robotics. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 4030.

137. Li, J.; Du, L.; Kong, X.; et al. Designing artificial ion channels with strict K+/Na+ selectivity toward next-generation electric-eel-mimetic ionic power generation. Natl. Sci. Rev. 2023, 10, nwad260.

138. Jiang, Q.; Liu, M. Recent progress in artificial neurons for neuromodulation. J. Funct. Biomater. 2024, 15, 214.

139. Pei, H.; Hu, H.; Dong, Y.; et al. Electric eels inspired iontronic artificial skin with multimodal perception and in‐sensor reservoir computing. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, 35, 2506431.

140. Wang, L.; Jiao, Y.; Zhang, H.; et al. Neuromorphic iontronic devices based on soft ionic conductors. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2026, 55, 299-335.

141. Ma, Y.; Niu, Y.; Pei, R.; Wang, W.; Wei, B.; Xie, Y. Reconfigurable neuromorphic computing by a microdroplet. Cell. Rep. Phys. Sci. 2024, 5, 102202.

142. Liu, W.; Mei, T.; Cao, Z.; et al. Bioinspired carbon nanotube-based nanofluidic ionic transistor with ultrahigh switching capabilities for logic circuits. Sci. Adv. 2024, 10, eadj7867.

143. Chen, L.; Ren, M.; Zhou, J.; et al. Bioinspired iontronic synapse fibers for ultralow-power multiplexing neuromorphic sensorimotor textiles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2024, 121, e2407971121.

144. Zhang, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Fan, Z.; et al. Self-powered multifunctional transient bioelectronics. Small 2018, 14, e1802050.

145. Zhang, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Sun, L.; Liu, Z.; Xia, X.; Tao, T. H. “Genetically engineered” biofunctional triboelectric nanogenerators using recombinant spider silk. Adv. Mater. 2018, 30, e1805722.

146. Zhang, Y.; Tao, T. H. Skin-friendly electronics for acquiring human physiological signatures. Adv. Mater. 2019, 31, e1905767.

147. Huang, T.; Zhang, Y.; He, P.; et al. “Self-matched” tribo/piezoelectric nanogenerators using vapor-induced phase-separated poly(vinylidene fluoride) and recombinant spider silk. Adv. Mater. 2020, 32, e1907336.

148. Turcu, D.; Zadina, A. N.; Abbott, L. F.; Sawtell, N. B. An end-to-end model of active electrosensation. Curr. Biol. 2025, 35, 2295-2306.e4.

149. Kostiainen, M. A.; Priimagi, A.; Timonen, J. V. I.; et al. Materials Inspired by Living Functions. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2402097.

150. Kim, S.; Eig, E.; Tian, B. The convergence of bioelectronics and engineered living materials. Cell. Reports. Physical. Science. 2024, 5, 102149.

Cite This Article

How to Cite

Download Citation

Export Citation File:

Type of Import

Tips on Downloading Citation

Citation Manager File Format

Type of Import

Direct Import: When the Direct Import option is selected (the default state), a dialogue box will give you the option to Save or Open the downloaded citation data. Choosing Open will either launch your citation manager or give you a choice of applications with which to use the metadata. The Save option saves the file locally for later use.

Indirect Import: When the Indirect Import option is selected, the metadata is displayed and may be copied and pasted as needed.

About This Article

Copyright

Data & Comments

Data

Comments

Comments must be written in English. Spam, offensive content, impersonation, and private information will not be permitted. If any comment is reported and identified as inappropriate content by OAE staff, the comment will be removed without notice. If you have any queries or need any help, please contact us at support@oaepublish.com.