Unveiling ion coordination in solid polymer electrolytes through alkyl chain length modulation in lithium salt chemistry

Abstract

Tuning the lithium salts’ chemistry is a promising approach to achieve a competitive solid polymer electrolyte (SPE). Lithium bis(trifluoromethanesulfonyl)imide (LiTFSI) has been extensively investigated due to its excellent thermal and electrochemical stability. On the other hand, poly(ethylene oxide) (PEO) remains one of the most studied polymer matrices owing to its high solvating power, which promotes lithium salt dissociation. However, the low lithium transference number (TLi+) of LiTFSI/PEO (ca. 0.2) system is a handicap for high-performance SPE, mainly attributed to the high anion diffusion. In this work, a series of five lithium salts were designed by replacing one -CF3 group of LiTFSI with a dialkylamine moiety bearing different alkyl chain lengths. Ion coordination environments between PEO, cations and anions, along with their transport properties, were systematically investigated through experimental and computational approaches. The results demonstrate that anion diffusion can be effectively suppressed by introducing bulky alkyl groups, with the improved TLi+ (ca. 0.5) primarily attributed to steric hindrance rather than long-range interactions between the anion and the PEO matrix.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

Energy storage systems have garnered significant attention as a solution for the implementation of renewable energy sources. Solid-state lithium metal batteries (SSLMBs) have become one of the most promising technologies to meet the demand for safer energy storage devices offering higher energy density, owing to the use of a solid-state electrolyte (SSE) coupled with a high-capacity lithium metal anode

Solid polymer electrolytes (SPEs) are facile to process, cost-effective compared to ceramic-based SSEs, and considerably safer than conventionally used liquid electrolytes[1,2,6]. Most commonly employed SPEs are composed of a polymer matrix possessing a strong solvating power where a lithium salt is dissolved[7]. As discussed in previous work, the ion transport in SPE is primarily driven by the segmental motion of the polymer chains or by anion-mediated continuous motion, depending on the lithium salt concentration[8]. As a result, optimal ionic conductivity in SPEs is typically attained in the amorphous phase at temperatures above the polymer’s glass transition temperature (Tg), where segmental motion plays a key role in facilitating ion transport. In this context, poly(ethylene oxide) (PEO) is the state-of-the-art (SoA) polymer host due to its high solvation ability and low Tg (-58 °C)[9,10]. In combination with PEO, lithium bis(trifluoromethanesulfonyl)imide (LiTFSI) is the most employed salt for SPEs due to its intrinsic structural anion flexibility through the S-N-S bond and highly delocalized negative charge[11]. Although the reference LiTFSI/PEO electrolyte exhibits high ionic conductivity (10-4 S cm-1) at temperatures exceeding its melting transition (Tm > 60 °C), it is subjected to significant cell concentration polarization ascribed to the high anionic mobility, which leads to lithium dendrite growth and consequently reduces battery performance[12-15].

Both polymer and anion chemistries play a crucial role in regulating cell concentration polarization by modulating lithium-ion conductivity. Within the electrolyte composition, the extent of lithium-ion mobility and low anion mobility are essential to ensure a high lithium transference number (TLi+) value, mitigating cell polarization. This, in turn, attains a more uniform lithium deposition, preventing or hindering lithium dendrite formation, which is the primary cause of end-of-life in SPE-based SSLMBs[16-18]. However, given that the reference LiTFSI/PEO system exhibits a low TLi+ of 0.2, it is clear that significant work remains to be done[19-21].

In recent years, different anion immobilization strategies have been designed targeting high TLi+. Focusing on the lithium salt, three key strategies can be highlighted: (1) anion tethering to a polymer backbone leading to single-ion conducting polymers, (2) use of additives to alter the lithium-ion mobility, and (3) design of novel anion structures to reduce its mobility. One of the most common approaches to develop single-ion conducting polymers is the polymerization of anion-containing monomers by radical polymerization to effectively restrict anion mobility[22-26]. The main challenge in this strategy lies in the development of the monomer itself. Thereby, lithium (4-styrenesulfonyl)(trifluoromethanesulfonyl)imide (LiSTFSI) and lithium propyl-sulfonyl(trifluoromethanesulfonyl)imide methacrylate (LiMTFSI) are among the most widely explored anions[27]. However, homopolymerization of these monomers typically results in rigid polymers. To overcome this, the reversible addition-fragmentation chain transfer (RAFT) technique can be utilized, providing precise control over the polymer’s chemical structure and molecular weight, which can promote segmental motion within the polymer phase[28-32]. These strategies enable TLi+ values above 0.9 to be reached, but the resulting ionic conductivities are typically in the range of 10-5 S cm-1 at

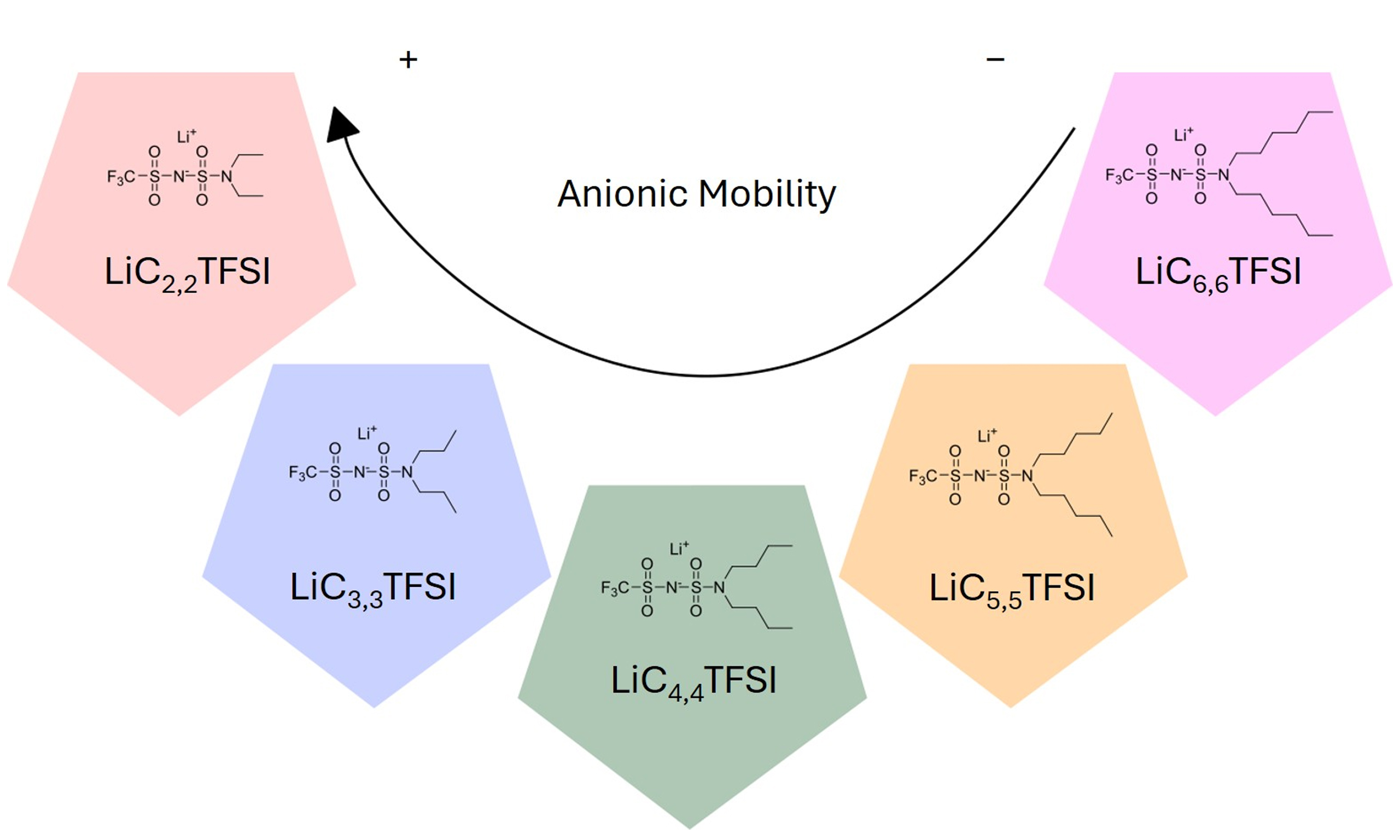

Despite significant advances regarding the improvement of the TLi+ value, a deeper understanding of the underlying phenomena governing ion mobility and conduction regarding the tuning of both the anion chemistry and anion size is lacking within the field. In this study, we propose a new amphiphilic lithium salt chemistry design strategy: substituting one -CF3 group of sulfonimide-based LiTFSI with a symmetric dialkylamine chain of varying lengths, ranging from 2 carbons [2,2] to six [6,6], as depicted in Figure 1. This chemical modification enables a systematic study of how the chain length influences the ion-ion and

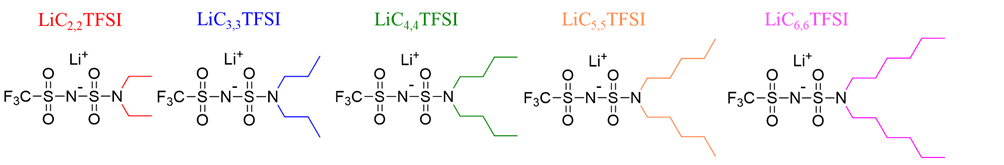

Figure 1. Chemical structure of the synthesized lithium salts. LiC2,2TFSI: Lithium(trifluoromethanesulfonyl)(N,N-diethylsulfamoyl)imide; LiC3,3TFSI: lithium(trifluoro-methanesulfonyl)(N,N-dipropylsulfamoyl)imide; LiC4,4TFSI: lithium(trifluoromethanesulfonyl) (N,N-dibutylsulfamoyl)imide; LiC5,5TFSI: lithium(trifluoromethanesulfonyl)(N,N-dipentyl-sulfamoyl)imide; LiC6,6TFSI: lithium(trifluoromethanesulfonyl)(N,N-dihexylsulfamoyl)-imide.

EXPERIMENTAL

Materials

PEO [Molecular weight (Mw) = 5 × 106 g mol-1], diethylamine (99+%), dipropylamine (99+%), dibutylamine (99+%), dipentylamine (99+%), dihexylamine (99+%), propylene carbonate (PC, 99.7%) and dimethoxyethane (DME, 99.5%) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Anhydrous acetonitrile (ACN, 99.9%), tert-butyl methyl ether (MTBE, 99.9%), magnesium sulfate anhydrous (MgSO4, 99.5%), ethanol (99.5%) and lithium carbonate (Li2CO3, 99%) were supplied by Thermo Fisher Scientific, whereas hexane, toluene (99.8%), and extra-pure hydrochloric acid (HCl, 37%) were purchased from Scharlab. Chlorosulfonyl (trifluoromethanesulfonyl)imide was purchased from Provisco, LiTFSI from Solvionic, and lithium metal disks (500 µm in thickness) from China Energy Lithium. All the chemicals have been used as received, except LiTFSI and the lithium metal disk. LiTFSI was dried at 100 °C, and under dynamic vacuum, and lithium metal disks were dried under dynamic vacuum at room temperature before their use in an argon-filled glove box.

Synthesis

For simplicity, the synthetic route for lithium(trifluoromethanesulfonyl)(N,N-diethylsulfamoyl)imide

Structural characterization

The chemical structure of the synthesized salt was confirmed by Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR), acquired with a Bruker 300 Ultrashield NMR instrument (300 MHz), in deuterated acetone [(CD3)2CO, 99.9%]. An inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometer (ICP-OES; HORIBA Scientific) was employed to quantitatively confirm that no excess lithium was present in the salt. A helium gas pycnometer (Micromeritics, AccuPyc II 1340) was used to analyze the density of the lithium salts.

Membrane preparation

PEO-based membranes were prepared by the solvent casting method. Dried lithium salts were taken from the glove box and were first dissolved in ACN. Subsequently, PEO was added to the respective solution. The solutions were left to stir overnight and then cast on a polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) dish. The solvent was evaporated in two steps: first, by drying in a ventilated oven at 35 °C for 24 h, followed by applying dynamic vacuum at 50 °C for 8 h. Membranes with a thickness of 150-220 µm were then prepared by hot-pressing, and subsequently dried at 50 °C under dynamic vacuum inside a glove box chamber. Six SPEs were prepared with an ethylene oxide:lithium cation (EO:Li) molar ratio of 20:1, using different lithium salts: LiC2,2TFSI, LiC3,3TFSI, LiC4,4TFSI, LiC5,5TFSI, and LiC6,6TFSI. For comparison, a reference SPE using LiTFSI with the same EO:Li ratio (20:1) was also prepared. Throughout this work, each SPE will be referred to as “lithium salt/PEO” to indicate the lithium salt used with the 20:1 EO:Li ratio.

Thermal characterization

Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) was performed for all the salts from room temperature to 600 °C at a heating rate of 10 °C min-1 under argon flow (flow of 60 mL min-1) with a TG 209F1 Libra (NETSCH) to determine the degradation temperature at which 5% of the mass is lost (Td,5%). The thermal transitions of the salt and polymer electrolytes were studied by differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) using a DSC2500 Discovery Series instrument. Cooling/heating scans at 1 °C min-1 were performed between -80 °C and

The crystallinity degree (χ), defined as the fraction of crystalline domains of the polymer electrolyte, was calculated using

where wt%PEO is the mass fraction of PEO in the SPE, ΔHm denotes the melting enthalpy of the electrolyte and ΔHPEO is the value of 196.4 J g-1 corresponding to the melting enthalpy of a fully crystalline PEO[19].

Raman spectroscopy

An InVia confocal Raman spectrometer (Renishaw; serial number 16H981; incident laser wavelength

Mechanical characterization

The static load cell (100 N2519 Series S-beam) had a displacement speed of 200 mm min-1. The samples had a thickness of 220 µm and a rectangular shape with dimensions of 40 mm in length and 10 mm in width. Young’s modulus was obtained using the tangent method in the elastic region.

Electrochemical characterization

Liquid electrolyte

The ionic conductivity of liquid electrolytes was measured by electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) using a VMP3 potentiostat (Biologic) at room temperature. Solutions of 1 M Lithium (trifluoromethanesulfonyl) (N,N-dialkylsulfamoyl)imide [LiCn,nTFSI (or LiTFSI)] in DME were prepared and analyzed with a two-electrode setup using black platinum plates (Radiometer Analytical, Hach). The ionic conductivity (σ) was calculated as:

where K and G refer to the electrode constant and the conductance of the electrolyte, respectively.

A three-electrode cell was used to analyze the oxidation of the salt at room temperature. Metallic lithium was used as both the reference and counter electrode, while platinum served as the working electrode. The electrolyte was composed of 0.1 M of LiCn,nTFSI (or LiTFSI) in PC. The linear sweep voltammetry (LSV) data were recorded using a VMP3 potentiostat (Biologic) at room temperature, at a scan rate of 0.1 mV s-1 from the open circuit voltage (OCV) up to 6.5 V vs. Li/Li+.

Solid electrolyte

To calculate the ionic conductivity of the solid electrolyte, the prepared SPEs (thickness from 150 to 200 µm and area 0.283 cm-2) were sandwiched between two stainless steel blocking electrodes in CR2032 coin cells (SS|SPE|SS) in an argon-filled glove box. The ionic conductivity value is determined using

where σ is the conductivity, l is the thickness of the membrane, A represents the area, and Rb signifies the resistance given by EIS.

To eliminate thermal history, the coin cells were kept at 100 °C for 10 h. Afterwards they were allowed to reach room temperature before starting the measurement. Measurements were carried out while increasing the temperature from 25 °C to 100 °C, with a 1 h stabilization period between different temperature measurements. Data were recorded using a VMP3 potentiostat (Biologic) in a frequency range of 1 MHz to 100 mHz with an amplitude of 10 mV.

To determine the diffusion coefficients of 7Li and 19F of SPEs, pulsed-field gradient nuclear magnetic resonance (PFG-NMR) has been required at variable temperatures (from 80 °C to 20 °C) with a Bruker Avance III 300 MHz wide-bore NMR spectrometer equipped with a 5 mm diff50 probe. Diffusion measurements of the nuclei were performed using Stimulated Echo. The diffusion time for both nuclei was about 25 ms, and the applied gradient pulse duration was 2 ms. The maximum field strength was 7.05 T, measured on a logarithmic scale. Recycle delay was set as 1 s, and 16 scans were accumulated. The lithium transport number tLi+ was calculated using

with DLi+ being the lithium diffusion and DAnion the anion diffusion[39].

Lithium symmetric cells [Li°|SPE (150-200 µm thick SPE)|Li°] in CR2032 coin cells were assembled in an argon-filled glove box. For the TLi+ determination, alternating current (AC) impedance and direct-current (DC) polarization measurements were performed in combination. Before the measurement, the cells were allowed to stabilize for 7 h at 40 °C and 70 °C. The Bruce-Vincent equation was used to calculate TLi+, as given below[40,41]:

where i0 and iSS are the currents at the beginning and at the end of the polarization, respectively, ∆V indicates the applied potential (10 mV), and RLi+,0 and RLi+,ss denote the lithium interfacial resistance before and after the polarization, respectively. The same cell configuration was used to determine the plating-striping performance at different currents, the diffusion and the concentration polarization of the SPEs. The galvanostatic C-rate cycling tests were performed employing the Biologic VMP3, applying different current densities (0.05, 0.1, 0.2, 0.3, 0.4, 0.5 mA cm-2) for 1 hour. An extended cycling test at 0.4 mA cm-2 was carried out for 75 h, with 1 h of plating and stripping and 24 h of rest. The Sand time was measured by galvanostatic analysis in VMP3 applying a current density of 30 µA cm-2 at 40 °C. The concentration polarization study was carried out by a galvanostatic cycling using a Maccor potentiostat with 24 h of resting, and a charge polarization at 50 µA cm-2 for 4 h at 70 °C[12]. The values of time were taken at 95% of the stabilized potential values. The diffusion is determined using:

where J is the current density, F represents the Faraday constant, c denotes the salt concentration in the electrolyte, DLi+ stands for the diffusion of the lithium, and τ signifies the Sand time[42].

Theoretical and computational details

Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations were performed using the Fritz Haber Institute Ab Initio Molecular Simulations (FHI-AIMS) software package[43,44]. The structures of TFSI- and Cn,nTFSI- (n,n = 2,2 - 5,5) were investigated. DFT calculations employed the B3LYP hybrid functional, which combines Becke’s three-parameter (B3) exchange functional with the Lee-Yang-Parr (LYP) correlation functional, together with the “tier2” standard basis set provided within FHI-AIMS[45,46].

The partial charges were scaled to - 0.7 for TFSI- and Cn,nTFSI- anions, and + 0.7 for Li+, with charge derived from the Electrostatic Potential (ESP) method[37,47-49]. A 10 Å cut-off was applied for van der Waals interactions and for the real-space component of the Ewald summation. Coulomb interactions in periodic systems were treated using the fast smooth Particle Mesh Ewald (PME) method[50,51].

Classical MD simulations using Gromacs were executed on LiTFSI(LiCn,nTFSI)/PEO SPE systems with an EO:Li ratio of 20:1 and a final simulation temperature of 70 °C[52,53]. The simulation boxes for

To determine the diffusion coefficient of salts, the Mean Square Displacement (MSD) was analyzed with the Einstein relation[60]:

where the diffusion coefficient of the species of interest is represented by D, the time elapsed during diffusion is represented by t, and ri(t) and ri(0) refer to the displacement travelled by species i at time t and at the origin, respectively.

The lithium-ion transport numbers (tLi+) by MD simulations can be expressed as:

where DLi+ refers to the lithium-ion diffusion coefficient, and DAnion indicates the diffusion coefficient of the anion, either TFSI- or Cn,nTFSI- species, where n,n = 2,2 - 5,5.

The Nernst-Einstein equation is given by:

where σi is the ionic conductivity, zi the valence (charge number) of the ion, q the elementary charge, ci the concentration of the ion in the electrolyte, Di the diffusion coefficient, Na the Avogadro’s constant, T the absolute temperature, and kb the Boltzmann constant.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSIONS

Thermal and electrochemical characterizations of the neat salts

A versatile two-step synthesis facilitated the tailoring of the lithium salt chemistry, as shown in Supplementary Scheme 2, leading to the upscaling synthesis of these salts compared to the reported

First, the intrinsic properties of the synthesized salts were evaluated. The impact of alkyl chain length on the thermal and electrochemical properties of the neat lithium salts was analyzed using TGA, DSC, and LSV

Understanding ion coordination and transport

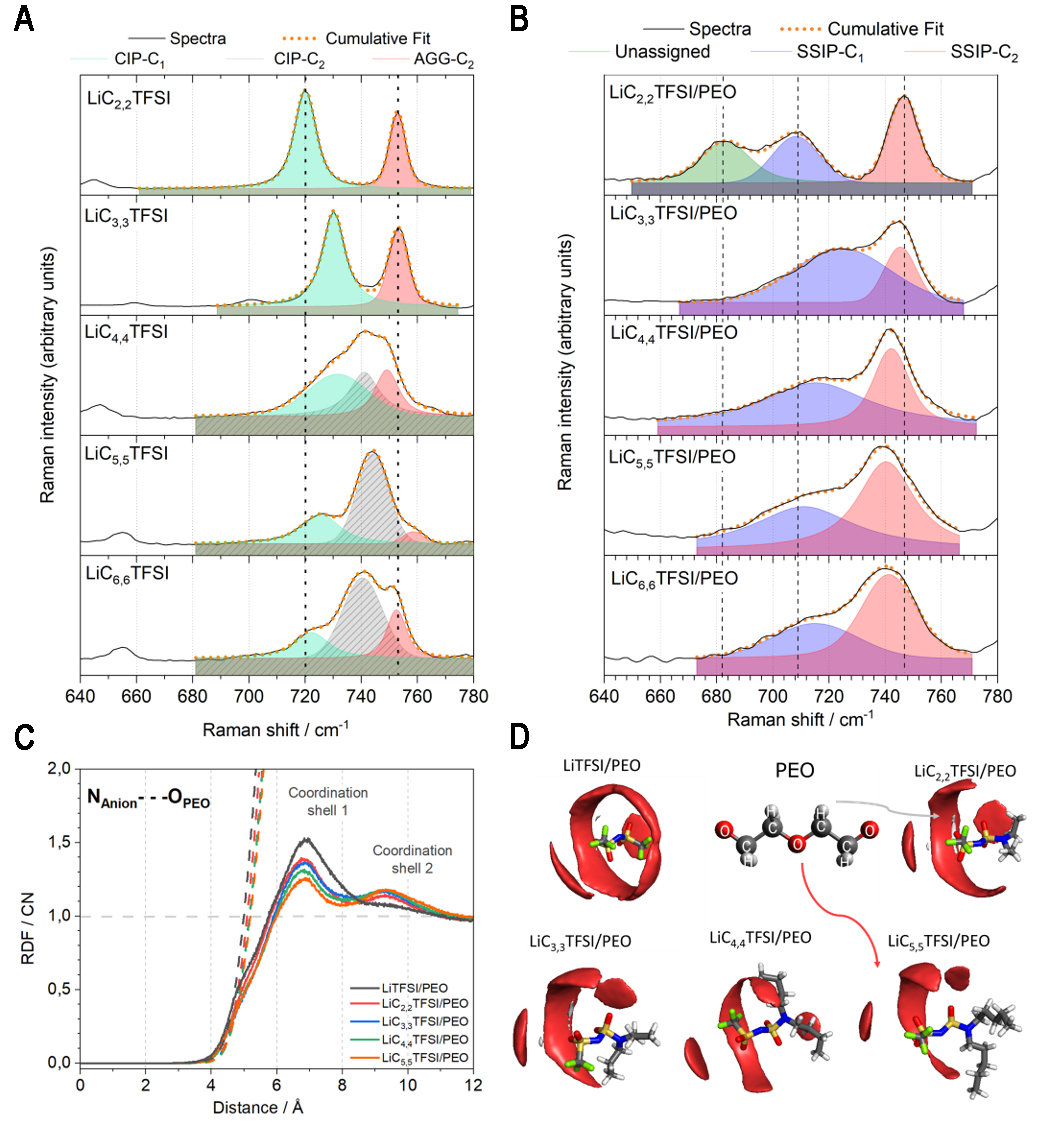

The tuning of the lithium salt chemistry from LiTFSI to the dialkylamine-based lithium salts was subsequently investigated in PEO, with an EO:Li ratio of 20:1, to unearth the impact of ionic structures and ion transport upon the final SPE properties. Elucidating the ion coordination environment provides detailed information regarding ion-ion interdependencies and molecular speciation changes. Within this scope, Raman spectroscopy was used to determine the anion coordination environment and the degree of dissociation of each lithium salt according to its chemistry. Additionally, the analysis has been complemented with MD simulations.

Given the novelty of the lithium salts and the similarity of TFSI- to Cn,nTFSI- anions regarding the S-N-S backbone, TFSI- was used as a reference. As reported, the S-N-S functional group is sensitive to interactions and conformational energy change within a 720-780 cm-1 vibrational window[68,69]. The coordinated form of LiTFSI is found at 747 cm-1, while the uncoordinated TFSI- form is found at 741 cm-1[68,70,71]. A notable downshift of the S-N-S vibration from the neat lithium salt spectra to the SPE spectra suggests nearly complete lithium salt dissociation, i.e., an absence of contact-ion pairs (CIPs). The apparent nearly complete lithium salt dissociation is ascribed to the high solvating power of the Ethylene Oxide (EO) units from PEO and the moderately diluted SPE concentration which avails sufficient O-atom sites from PEO for lithium-ion coordination.

Examining the Raman spectra of the neat salts [Figure 2A], both LiC2,2TFSI and LiC3,3TFSI display two distinct peaks, which appear as deconvoluted spectra starting from LiC4,4TFSI onwards. Compared to neat LiTFSI, a single Raman band consisting of CIP, with TFSI- ions bidentately coordinated to a single lithium ion in cisoid (C1) conformation, has been extensively reported[68,72]. Studies on the conformational changes of LiTFSI indicate that the C1 conformation, with both -CF3 groups on the same side of the S-N-S plane, is found at lower wavenumbers compared to the transoid conformer (C2), with the two -CF3 moieties on opposite sides of the S-N-S plane[69,71,73]. When TFSI- is coordinated to the lithium ion, C1 conformation is preferred, while the solvent-separated ion pair (SSIP) (uncoordinated TFSI-) is present as the C2 conformation when LiTFSI is found in PEO[49,68,72]. Considering the asymmetry of the amphiphilic lithium salts, comprised of both non-polar -[N(CH2)n-1(CH3)]n and polar -CF3 moieties, various conformational modes may influence the expansion-contraction mode of the S-N-S vibration, resulting in distinct Raman spectra as a function of the dialkylamine chain length. Based on the different solvate structures of the neat lithium salts, such as CIP, aggregate (AGG) (i.e., at least two O-atoms from the anion coordinates to two or more lithium ions) and SSIP coordination types, either C1 or C2 conformations may prevail depending on the chemical environment[72,74].

Figure 2. Coordination environment analysis: Raman spectra illustrating the S-N-S vibration for (A) neat LiCn,nTFSI salts at room temperature and (B) LiCn,nTFSI/PEO at 70 °C; (C) Radial Distribution Functions (RDFs) (solid lines) with the anion as the reference ion, and PEO as the observed species, via their N-atom and O-atoms, respectively. The coordination numbers (CNs) are shown as dashed lines; (D) Spatial Distribution Functions (SDFs) of LiCn,nTFSI/PEO. The red and grey iso-surfaces represent the distribution of O-atoms and H-atoms from PEO, respectively. RDFs and SDFs were computed from MD simulations at 70 °C. LiC2,2TFSI: Lithium(trifluoromethanesulfonyl)(N,N-diethylsulfamoyl)imide; LiC3,3TFSI: lithium(trifluoro-methanesulfonyl)(N,N-dipropylsulfamoyl)imide; LiC4,4TFSI: lithium(trifluoromethanesulfonyl) (N,N-dibutylsulfamoyl)imide; LiC5,5TFSI: lithium(trifluoromethanesulfonyl)(N,N-dipentyl-sulfamoyl)imide; LiC6,6TFSI: lithium(trifluoromethanesulfonyl)(N,N-dihexylsulfamoyl)-imide; PEO: poly(ethylene oxide); MD: molecular dynamics.

Upon Raman peak deconvolution [Supplementary Figure 20 and Supplementary Table 4] of the neat lithium salts, LiC2,2TFSI and LiC3,3TFSI display two distinct coordination types, while the remaining lithium salts exhibit three coordination types. The Raman band present at the lowest wavenumber is ascribed to CIP-C1 while the band at a higher wavenumber is ascribed to the AGG-C2 conformation. The central band of LiCn,nTFSI from n,n = 4,4 to 6,6; ranging from 740 cm-1 to 742 cm-1, is hypothesized to be CIP-C2 where a sterically constrained or asymmetric environment is foreseen. These assignments are hypothesized as based on identifying similar solvation structures from previous studies on TFSI- and FSI-[68,72].

Regarding the SPEs, upon Raman deconvolution, two distinct Raman bands are detected for the respective amphiphilic-based SPEs, while LiC2,2TFSI/PEO exhibits three Raman bands [Figure 2B and Supplementary Table 5]. Considering the amphiphilic SPEs from [n,n] = [3,3] to [6,6], the Raman band at a higher wavenumber is ascribed to the SSIP-C2 form. The 2nd Raman band (i.e., 710 cm-1), observed for all the amphiphilic SPEs, is assigned to SSIP-C1. The 3rd Raman band, observed at 680 cm-1 for LiC2,2TFSI/PEO, can be assigned to the carbon-sulfur (C-S) bond. This mode is generally absent in LiTFSI/PEO due to the weak change in polarizability associated with the vibration. However, in the case of LiC2,2TFSI/PEO, the asymmetry of the anion may enhance the polarizability change, allowing the C-S vibration to be detected[75]. Overall, Raman spectroscopy analysis shows that the lithium salt is nearly completely dissociated in PEO, regardless of the lithium salt chemistry.

To gain a deeper understanding of the fundamental ion coordination environment and the impact of lithium salt chemistry on ion transport, classical MD simulations were performed. Specifically, classical MD simulations can effectively probe the impact of anion chemistry upon the lithium and anion coordination environment and may be used to determine (i) the extent of ion association or dissociation in PEO, (ii) the positioning of species surrounding a species of interest, and (iii) the quantification of ion-specific speciation. LiC6,6TFSI/PEO is excluded from the MD study due to partial charge method limitations, resulting in inaccurately capturing ion dynamics and erroneous coordination analysis.

In Supplementary Figure 21A and B, Radial Distribution Functions (RDFs) are presented with lithium ions selected as the reference species, demonstrating lithium ions interacting with O atoms from either

To assess the impact of the non-polar moiety on the anion coordination environment, RDFs were computed employing the N-atom from the respective anions as the reference, and the O-atom from PEO as the observed species, as shown in Figure 2C. The slight decrease in the RDF peak intensities-observed at 7 and 9 Å-with increasing dialkylamine chain length suggests a modest reduction in the long-range interactions of the respective anions by PEO. This trend may be linked to the combined effects of increasing non-polar character and the larger anion size, both of which can slightly diminish the extent of PEO solvation around the anions. However, given the small magnitude of the changes observed, these conclusions should be interpreted with caution and viewed as indicative rather than definitive.

To further illustrate the local interaction environment, a visual representation of the RDF analysis was performed using spatial distribution functions (SDFs) [Figure 2D]. SDFs display the statistical distribution of PEO atoms around the anions, with red and grey iso-surfaces representing the positions of O atoms and H atoms from PEO, respectively. Within a 10 Å cut-off distance, PEO O atoms are predominantly found surrounding the central backbone of the anions, with the most extensive long-range interactions observed for LiC2,2TFSI/PEO. These interactions gradually decrease such that, for LiC5,5TFSI/PEO, O atoms are primarily located around the -CF3 moieties. This analysis tentatively suggests that PEO preferentially interacts with the anion around the -CF3 groups, a feature especially pronounced in the case of LiTFSI/PEO. This supports the interpretation that increasing the non-polar character of the anion reduces its overall interaction with PEO. Additionally, a minor presence of H atoms from PEO in close proximity to the central N atom was observed, predominantly for LiC2,2TFSI/PEO, LiC3,3TFSI/PEO, and LiTFSI/PEO.

To identify and quantify ion-ion interactions around lithium ions, molecular speciation analysis was performed. As shown in Supplementary Figure 22, using a cut-off of 3 Å, lithium-ion speciation was similar across all systems, regardless of dialkylamine chain length or anion chemistry. In all cases, lithium ions predominantly coordinate with PEO chains (≥ 98 %), forming Li+-O-PEO interactions. A minor population of lithium ions coordinating simultaneously with both PEO and anions (Li+-PEO-Anion) was also observed for all the SPEs. These results reaffirm that lithium ions are largely solvated by PEO, with only a small contribution from direct anion-cation interactions.

Upon elucidation of ion coordination at the atomistic scale, mesoscale dynamics were investigated to assess the impact of the lithium salt on bulk SPE properties. Polymer chain dynamics, in particular, are an important feature of SPEs, influencing ion transport and electrochemical properties. Therefore, the thermal and electrochemical properties of the corresponding five SPEs were analyzed. Regarding the thermal transitions determined by DSC [Supplementary Figure 23 and Supplementary Table 6], a slight trend of decreasing Tg and an increase of crystalline fraction (χc) are noticed with increasing dialkylamine chain length of the salt anion. The Tg value of LiCn,nTFSI/PEO decreases from [2,2] to [6,6], ranging from -30 °C for LiC2,2TFSI/PEO to -42 °C for LiC6,6TFSI/PEO. This suggests that longer dialkylamine anions promote polymer flexibility, which may be ascribed to the lower degree of anion-polymer interactions with an increasing dialkylamine chain length. In the same vein, the stronger interaction of smaller anions with the polymer chains is translated into a higher amorphization effect, as demonstrated by the decrease in crystallinity. Thus, the crystallinity degree varies from 59% for LiC2,2TFSI/PEO to 65% for LiC6,6TFSI/PEO. Comparing these values with SoA LiTFSI/PEO, a slight decrease of the Tm (57 °C) and ΔHm (73 J g-1) is observed, leading to a decreased crystallinity degree (49%) compared to the synthesized salts. This suggests that a lower degree of crystallinity may be associated with a more favorable interaction between the polymer chains and the anion, particularly when the anion presents a smaller size and a more flexible structure, which is consistent with SDF analysis from MD simulations. Additionally, the Young modulus has been measured for LiTFSI/PEO (20.5 ± 2.8 MPa), LiC2,2TFSI/PEO (29.2 ± 8.6 MPa) and LiC6,6TFSI/PEO (27.7 ± 5.1 MPa). These results indicate that the addition of the dialkyl chain slightly increases the polymer’s resistance, making the SPE stiffer.

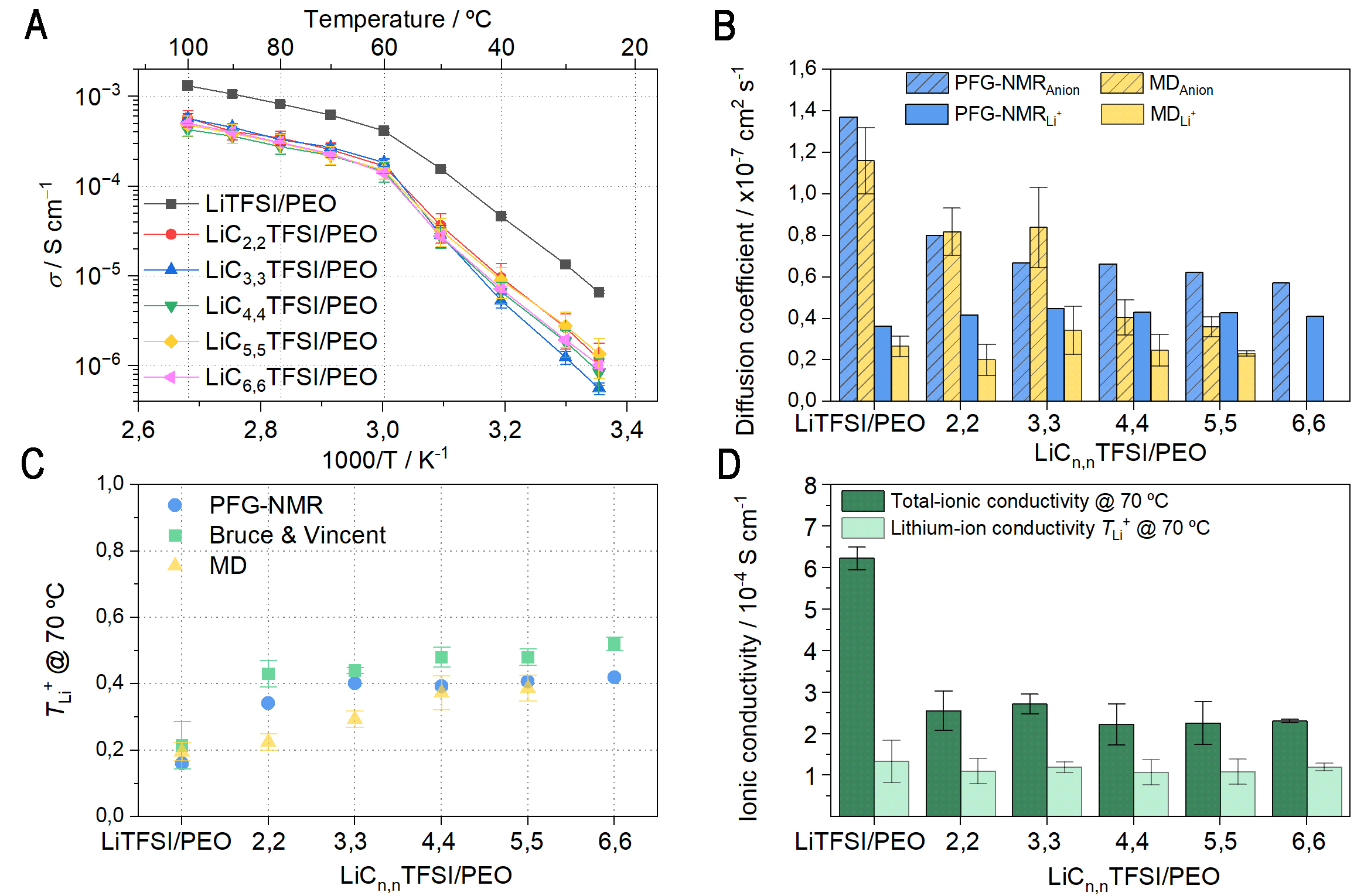

Following the thermal analysis, transport properties were investigated. In Figure 3A and Supplementary Table 6, the total ionic conductivity is plotted against temperature. For all SPEs, the Arrhenius plots present two trends with an inflection point at 60 °C, corresponding to the melting of the polymer matrix (see Supplementary Figure 23 and Supplementary Table 6). The bulky structure of the anion decreases the total ionic conductivity (from 2.55 × 10-4 S cm-1 for LiC2,2TFSI/PEO to 2.30 × 10-4 S cm-1 for LiC6,6TFSI/PEO, whereas LiTFSI/PEO provides a total ionic conductivity of 6.22 × 10-4 S cm-1 at 70 °C). Overall, for the

Figure 3. Analysis of PEO-SPEs consisting of the following lithium salts: LiCn,nTFSI [2,2; 3,3; 4,4; 5,5; 6,6] and LiTFSI (EO:Li ratio 20:1); (A) Ionic conductivity as a function of temperature; (B) Diffusion coefficients measured by PFG-NMR and MD simulations; (C) TLi+ at

To elucidate the significant decrease in ionic conductivity of the novel lithium salts- and LiTFSI-SPEs, ion transport properties were studied at 70 °C using PFG-NMR, electrochemical analysis, and MD simulations. The diffusion coefficients of the lithium-ion and anions were determined first. Figure 3B and Supplementary Table 7 display the experimentally obtained (PFG-NMR) and computed lithium-ion (DLi+) and anion (DAnion) diffusion coefficients of the studied PEO-based SPEs. At first glance, PFG-NMR shows a moderate increase in DLi+ from 2.4 × 10-8 cm2 s-1 for LiTFSI/PEO to 4.2 × 10-8 cm2 s-1 for LiC2,2TFSI/PEO. However, upon increasing the dialkylamine chain length, the DLi+ remains unchanged (4.1 × 10-8 cm2 s-1 for LiC6,6TFSI/PEO). The major difference in ion transport is noted for the anion, with DAnion consistently slower in all the novel SPEs compared to the reference LiTFSI/PEO (12.7 × 10-8 cm2 s-1). Moreover, the DAnion decreases with an increase in the dialkylamine chain length, from 8.0 × 10-8 cm2 s-1 for LiC2,2TFSI/PEO to 5.7 × 10-8 cm2 s-1 for LiC6,6TFSI/PEO, reinforcing the fact that the bulkier the anion, the slower the anionic mobility. MD-computed diffusion coefficients are in good agreement with PFG-NMR data even if they are somewhat underestimated for longer dialkylamine chain SPEs. In particular, the MD-computed DAnion of LiC3,3TFSI/PEO is slightly overestimated compared to PFG-NMR, i.e., 8.4 × 10-8 cm2 s-1 versus 6.7 ×

The Li transference (TLi+) and transport (tLi+) numbers were calculated to gain deeper insight into the ion transport properties. Electrochemical techniques combining EIS and chronoamperometry (CA), and PFG-NMR are well-established for determining the TLi+/tLi+. First, electrochemical measurements of TLi+ were performed, and data are presented in Figure 3C and Supplementary Table 6. A significant increase in TLi+ values was observed when moving from LiTFSI/PEO to LiC2,2TFSI/PEO, with values of 0.21 and 0.43, respectively, as measured by EIS-CA at 70 °C. Upon further increasing the length of the dialkylamine chain, TLi+ continued to moderately rise across the remaining SPEs, reaching 0.48 for both LiC4,4TFSI/PEO and LiC5,5TFSI/PEO, and 0.52 for LiC6,6TFSI. It is worth noting that similar TLi+ values were obtained for

Overall, the consistent trend across all methods highlights that increasing the dialkylamine chain length leads to higher TLi+ and tLi+ values. This improvement could be attributed to a two-fold effect: bulkier anions and lower interaction with PEO. Nevertheless, as reported in the literature, a lower interaction between the anion and PEO should lead to a higher anion diffusivity[76]. Therefore, the results suggest that the size of the anions is the primary factor contributing to the reduced anion mobility rather than the PEO-anion interactions. This appears to counterbalance the slightly weaker interaction of longer chain lengths with PEO, as observed in the RDF. This effect reduces anion diffusion coefficients [Supplementary Tables 7 and 9] and their contribution to the total ionic conductivity.

Finally, the lithium-ion conductivity was determined by multiplying the TLi+ values by the total ionic conductivity, as shown in Figure 3D. While the total ionic conductivity decreases markedly when replacing one trifluoromethyl group by the dialkylamine functionality, the lithium-ion conductivity remains comparable (≈ 1.2 × 10-4 S cm-1 at 70 °C), which can be attributed to the same CN regardless of the anion chemistry. This observation is of significant importance, as only Li+ contributes to the electrochemical function of the SSLMB. In contrast, the diffusion of the anion may adversely affect cell performance by promoting the formation of concentration gradients, which can result in inhomogeneous lithium plating and, ultimately, lead to cell failure[13,18,77,78]. To further prove the importance of the improved lithium transport properties of the developed novel lithium salts, the (electro)chemical compatibility with lithium metal anode will be assessed.

Electrochemical compatibility with lithium metal anode

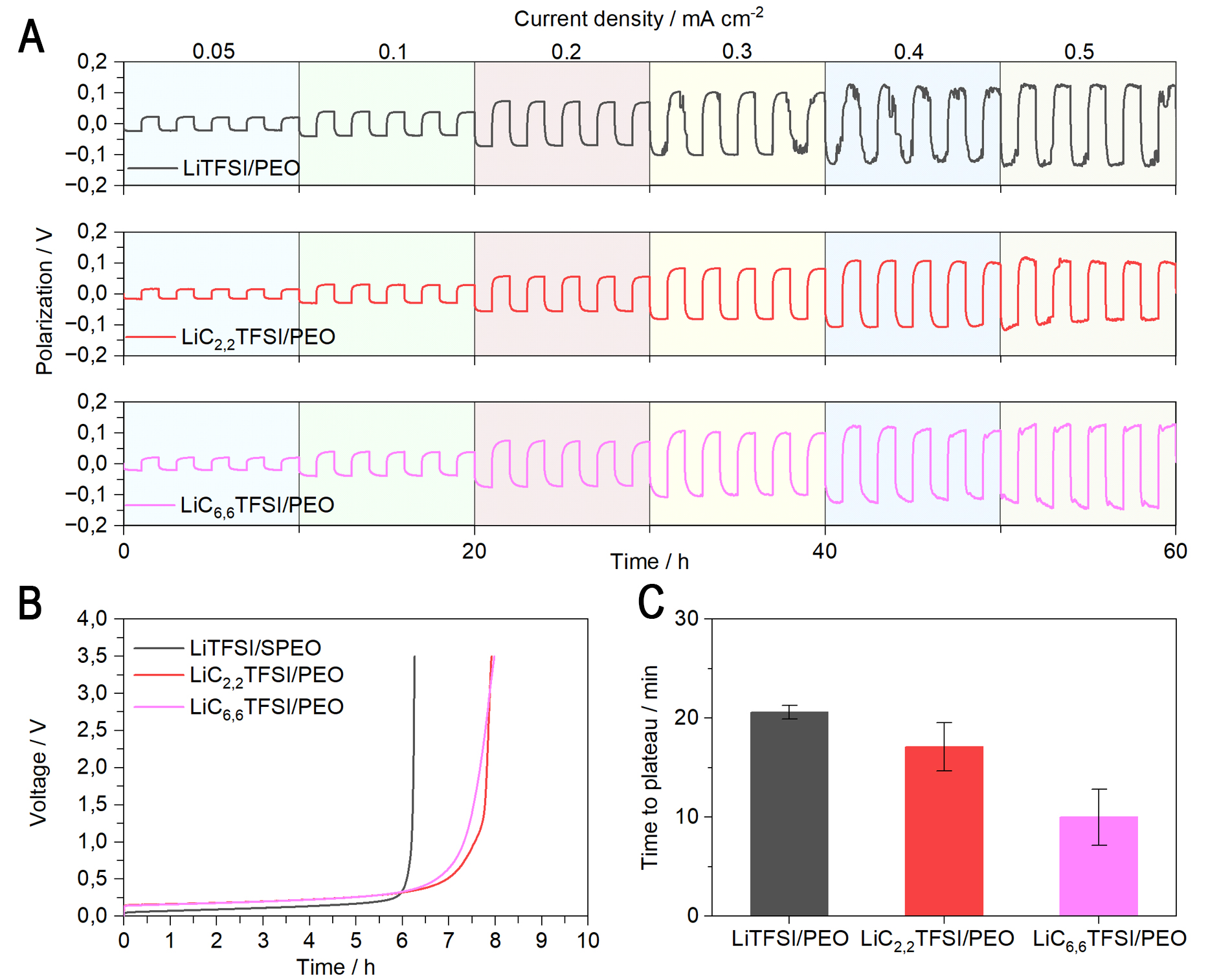

Within this scope, the performance of SPEs was investigated in a lithium symmetric cell configuration. The impact of lithium salt chemistry on key SPE properties, including critical current density, Sand time, and concentration polarization, was assessed[42,79]. Considering previous results where only small variations were observed in transport properties ascribed to anion’s dialkylamine chain length, and to simplify the analysis, only SPEs with the lowest and highest dialkylamine chain length salts were selected for further studies:

Figure 4. (A) C-rate plot at 70 °C consisting in 5 cycles of two hours at 0.05, 0.1, 0.2, 0.3, 0.4, and 0.5 mA cm-2; (B) Voltage profile as a function of time, with a current density of 50 µA cm-2 with a record time of 10 s at 40 °C; (C) Polarization concentration plot of symmetric cells Li|SPE|Li, EO:Li 20:1 of LiTFSI/PEO, LiC2,2TFSI/PEO, and LiC6,6TFSI/PEO of 0.05 mA cm-2 for 4 h at 70 °C. PEO: Poly(ethylene oxide); LiC2,2TFSI: Lithium(trifluoromethanesulfonyl)(N,N-diethylsulfamoyl)imide; LiC6,6TFSI: lithium(trifluoromethanesulfonyl)(N,N-dihexylsulfamoyl)-imide; EO:Li: ethylene oxide:lithium cation; SPE: solid polymer electrolyte.

The depletion of lithium from the SPE was then evaluated at 40 °C [Figure 4B]. This characterization, known as the Sand method, records the polarization evolution over time and determines the period during which the lithium-ion concentration is near zero at the electrode surface. This occurs when lithium depletion is faster than the transport of lithium ions. Using a 0.5 V polarization increase as the criterion for lithium depletion, the LiC2,2TFSI/PEO cell reached depletion at 7.2 h, and the LiC6,6TFSI/PEO cell at 7 h, both delayed compared with the LiTFSI/PEO cell, which showed depletion at 6.1 h. These results support the C-rate test findings, in which anion immobilization enhances cell performance. The lithium diffusion, calculated according to the Sand equation, is decreasing as follows: the highest for LiC6,6TFSI (3.26 ×

Concentration polarization through the SPE was also assessed by a more specific characterization

CONCLUSIONS

This work explores the influence of anion chemistry on dialkylamine chain length. A series of novel lithium salts were synthesized and thoroughly investigated for their ion coordination and ion transport properties using a combination of experimental and computational techniques:

• Lithium-ion coordination remained constant across different anion chemistries and dialkylamine chain lengths, as evidenced by the strong coordination between the lithium cation and PEO, visualized through RDF analysis.

• Long-ranged interactions between the anion and PEO decreased with increasing chain length, as observed by SDF analysis and supported by DSC analysis (lower crystalline degree: 59% for LiC2,2TFSI/PEO and 65% for LiC6,6TFSI/PEO and lower Tg: -30 °C for LiC2,2TFSI and -42 °C for LiC6,6TFSI).

• Ionic conductivity and diffusion coefficients were evaluated using EIS, MD simulations, and PFG-NMR, showing a competitive TLi+/tLi+ (ca. 0.5), which resulted from reduced anion diffusion due to the presence of a bulky structure. This decrease in anion mobility did not negatively impact Li+ conductivity, leading to a notable enhancement in C-rate cyclability and a reduction in concentration polarization.

The findings highlight a delicate balance between ionic conductivity, anion diffusion, and TLi+/tLi+. This work demonstrates the potential of tuning anion chemistry as a function of dialkylamine chain length to optimize SPEs properties. Moreover, in addition to their high TLi+, these lithium salts are attractive for large-scale production due to their ease of synthesis. Supplementary Table 11 shows a comparative overview of this work compared to previously reported salts. These insights are crucial for modifying lithium salts to enhance lithium-ion transference numbers while preserving lithium ionic conductivity to diminish the concentration gradient.

DECLARATIONS

Author’s contributions

Writing original draft, experimental analysis and editing: Neumann, P.; Fortuin, B. A.; Meabe, L.

Experimental contributions, reviewing and editing: Sasieta-Barrutia, E.; Meabe, L.; Garcia, L.; Zhang, Y.

Reviewing and editing: Morant-Miñana, M. C.; Forsyth, M.; Carrasco, J.; Lecuyer, M.; Deschamps, M.; Zhang, H.; Armand, M.; Martinez-Ibañez, M.

Conceptualization and funding: Meabe, L.; Armand, M.; Martinez-Ibañez, M.

Availability of data and materials

The data supporting this study are available within the article and the Supplementary Materials. Supplementary Tables and Figures including the synthetic route, chemical structures, NMR spectroscopy, lithium-ion and anion speciation analyses, RDF analyses and forcefield parameters for the different studied systems. This material is available free of charge.

Financial support and sponsorship

Meabe, L.; Garcia, L.; Forsyth, M.; Zhang, Y.; Carrasco, J.; Martinez-Ibañez, M. acknowledge financial support from PID2022-143003OB-I00, funded by MICIU/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 and by ESF+. B.F. acknowledges financial support from the DESTINY PhD program, funded by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie Actions COFUND (Grant Agreement No. 945357). The authors also thank SGI/IZO-SGIker UPV/EHU for providing supercomputing resources.

Conflicts of interest

Lecuyer, M. and Deschamps, M. are affiliated with Blue Solutions by Bolloré, while the other authors have declared that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2025.

Supplementary Materials

REFERENCES

1. Xia, S.; Wu, X.; Zhang, Z.; Cui, Y.; Liu, W. Practical challenges and future perspectives of all-solid-state lithium-metal batteries. Chem 2019, 5, 753-85.

2. An, Y.; Han, X.; Liu, Y.; et al. Progress in solid polymer electrolytes for lithium-ion batteries and beyond. Small 2022, 18, e2103617.

3. He, M.; Hector, L. G.; Dai, F.; et al. Industry needs for practical lithium-metal battery designs in electric vehicles. Nat. Energy. 2024, 9, 1199-205.

4. Cheng, X. B.; Zhang, R.; Zhao, C. Z.; Zhang, Q. Toward safe lithium metal anode in rechargeable batteries: a review. Chem. Rev. 2017, 117, 10403-73.

5. Fenton, D.; Parker, J.; Wright, P. Complexes of alkali metal ions with poly(ethylene oxide). Polymer 1973, 14, 589.

6. Mindemark, J.; Lacey, M. J.; Bowden, T.; Brandell, D. Beyond PEO-Alternative host materials for Li+-conducting solid polymer electrolytes. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2018, 81, 114-43.

7. Sundararaman, S.; Halat, D. M.; Choo, Y.; et al. Exploring the ion solvation environments in solid-state polymer electrolytes through free-energy sampling. Macromolecules 2021, 54, 8590-600.

8. Gudla, H.; Hockmann, A.; Brandell, D.; Mindemark, J. To hop or not to hop: unveiling different modes of ion transport in solid polymer electrolytes through molecular dynamics simulations. ACS. Appl. Polym. Mater. 2025, 7, 4716-24.

9. Kalhoff, J.; Eshetu, G. G.; Bresser, D.; Passerini, S. Safer electrolytes for lithium-ion batteries: state of the art and perspectives. ChemSusChem 2015, 8, 2154-75.

10. Cameron, G. G.; Ingram, M. D.; Sorrie, G. A. The mechanism of conductivity of liquid polymer electrolytes. J. Chem. Soc. Faraday. Trans. 1. 1987, 83, 3345.

11. Xue, Z.; He, D.; Xie, X. Poly(ethylene oxide)-based electrolytes for lithium-ion batteries. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2015, 3, 19218-53.

12. Yu, X.; Jiang, X.; Seidler, M. E.; et al. Nanostructured ionic separator formed by block copolymer self-assembly: a gateway for alleviating concentration polarization in batteries. Macromolecules 2022, 55, 2787-96.

13. Cao, D.; Sun, X.; Li, Q.; Natan, A.; Xiang, P.; Zhu, H. Lithium dendrite in all-solid-state batteries: growth mechanisms, suppression strategies, and characterizations. Matter 2020, 3, 57-94.

14. Wu, B.; Wang, S.; Lochala, J.; et al. The role of the solid electrolyte interphase layer in preventing Li dendrite growth in solid-state batteries. Energy. Environ. Sci. 2018, 11, 1803-10.

15. Khurana, R.; Schaefer, J. L.; Archer, L. A.; Coates, G. W. Suppression of lithium dendrite growth using cross-linked polyethylene/poly(ethylene oxide) electrolytes: a new approach for practical lithium-metal polymer batteries. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 7395-402.

16. Sun, C.; Liu, J.; Gong, Y.; Wilkinson, D. P.; Zhang, J. Recent advances in all-solid-state rechargeable lithium batteries. Nano. Energy. 2017, 33, 363-86.

17. Yang, S.; Lee, S.; Kang, M. S.; et al. Insights into improving the li-ion transference number and li deposition uniformity toward a high-current-density lithium metal anode. Carbon. Energy. 2025, 7, e70053.

18. Liu, J.; Yuan, H.; Liu, H.; et al. Unlocking the failure mechanism of solid state lithium metal batteries. Advanced. Energy. Materials. 2022, 12, 2100748.

19. Stolwijk, N. A.; Heddier, C.; Reschke, M.; Wiencierz, M.; Bokeloh, J.; Wilde, G. Salt-concentration dependence of the glass transition temperature in PEO-NaI and PEO-LiTFSI polymer electrolytes. Macromolecules 2013, 46, 8580-8.

20. Martinez-ibañez, M.; Sanchez-diez, E.; Oteo, U.; et al. Anions with a dipole: toward high transport numbers in solid polymer electrolytes. Chem. Mater. 2022, 34, 3451-60.

21. Lin, L.; Chen, C. Accurate characterization of transference numbers in electrolyte systems. J. Power. Sources. 2024, 603, 234236.

22. Zhu, J.; Zhang, Z.; Zhao, S.; Westover, A. S.; Belharouak, I.; Cao, P. Single-ion conducting polymer electrolytes for solid-state lithium-metal batteries: design, performance, and challenges. Adv. Energy. Mater. 2021, 11, 2003836.

23. Shah, D. B.; Olson, K. R.; Karny, A.; Mecham, S. J.; Desimone, J. M.; Balsara, N. P. Effect of anion size on conductivity and transference number of perfluoroether electrolytes with lithium salts. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2017, 164, A3511-7.

24. Wang, S.; Jeung, S.; Min, K. The effects of anion structure of lithium salts on the properties of in-situ polymerized thermoplastic polyurethane electrolytes. Polymer 2010, 51, 2864-71.

25. Zhang, H.; Oteo, U.; Zhu, H.; et al. Enhanced lithium-ion conductivity of polymer electrolytes by selective introduction of hydrogen into the anion. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 7829-34.

26. Scheers, J.; Niedzicki, L.; Zukowska, G. Z.; Johansson, P.; Wieczorek, W.; Jacobsson, P. Ion-ion and ion-solvent interactions in lithium imidazolide electrolytes studied by Raman spectroscopy and DFT models. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2011, 13, 11136-47.

27. Porcarelli, L.; Shaplov, A. S.; Salsamendi, M.; et al. Single-ion block copoly(ionic liquid)s as electrolytes for all-solid state lithium batteries. ACS. Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2016, 8, 10350-9.

28. Jangu, C.; Savage, A. M.; Zhang, Z.; et al. Sulfonimide-containing triblock copolymers for improved conductivity and mechanical performance. Macromolecules 2015, 48, 4520-8.

29. Rolland, J.; Poggi, E.; Vlad, A.; Gohy, J. Single-ion diblock copolymers for solid-state polymer electrolytes. Polymer 2015, 68, 344-52.

30. Sadoway, D. R.; Huang, B.; Trapa, P. E.; Soo, P. P.; Bannerjee, P.; Mayes, A. M. Self-doped block copolymer electrolytes for solid-state, rechargeable lithium batteries. J. Power. Sources. 2001, 97-98, 621-3.

31. Ryu, S.; Trapa, P. E.; Olugebefola, S. C.; Gonzalez-leon, J. A.; Sadoway, D. R.; Mayes, A. M. Effect of counter ion placement on conductivity in single-ion conducting block copolymer electrolytes. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2005, 152, A158.

32. Gao, J.; Wang, C.; Han, D. W.; Shin, D. M. Single-ion conducting polymer electrolytes as a key jigsaw piece for next-generation battery applications. Chem. Sci. 2021, 12, 13248-72.

33. Stolz, L.; Hochstädt, S.; Röser, S.; Hansen, M. R.; Winter, M.; Kasnatscheew, J. Single-ion versus dual-ion conducting electrolytes: the relevance of concentration polarization in solid-state batteries. ACS. Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2022, 14, 11559-66.

34. Chen, H.; Zheng, M.; Qian, S.; et al. Functional additives for solid polymer electrolytes in flexible and high-energy-density solid-state lithium-ion batteries. Carbon. Energy. 2021, 3, 929-56.

35. Meng, Y.; Hu, J.; Yu, Q.; et al. Trace filling strategy of amphoteric molecules for large-capacity and long-lasting Li-Fe-F conversion all-solid-state batteries. J. Energy. Chem. 2025, 110, 153-64.

36. Qiao, L.; Rodriguez, Peña. S.; Martínez-Ibañez, M.; et al. Anion π-π stacking for improved lithium transport in polymer electrolytes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 9806-16.

37. Fortuin, B. A.; Meabe, L.; Peña, S. R.; et al. Molecular-level insight into charge carrier transport and speciation in solid polymer electrolytes by chemically tuning both polymer and lithium salt. J. Phys. Chem. C. Nanomater. Interfaces. 2023, 127, 1955-64.

38. Lu, N.; Ho, Y.; Fan, C.; Wang, F.; Lee, J. A simple method for synthesizing polymeric lithium salts exhibiting relatively high cationic transference number in solid polymer electrolytes. Solid. State. Ionics. 2007, 178, 347-53.

39. Sethurajan, A. K.; Krachkovskiy, S. A.; Halalay, I. C.; Goward, G. R.; Protas, B. Accurate characterization of ion transport properties in binary symmetric electrolytes using in situ NMR imaging and inverse modeling. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2015, 119, 12238-48.

40. Evans, J.; Vincent, C. A.; Bruce, P. G. Electrochemical measurement of transference numbers in polymer electrolytes. Polymer 1987, 28, 2324-8.

41. Bruce, P. G.; Vincent, C. A. Steady state current flow in solid binary electrolyte cells. J. Electroanal. Chem. Interfacial. Electrochem. 1987, 225, 1-17.

42. Stolz, L.; Homann, G.; Winter, M.; Kasnatscheew, J. The Sand equation and its enormous practical relevance for solid-state lithium metal batteries. Mater. Today. 2021, 44, 9-14.

43. Havu, V.; Blum, V.; Havu, P.; Scheffler, M. Efficient integration for all-electron electronic structure calculation using numeric basis functions. J. Comput. Phys. 2009, 228, 8367-79.

44. Blum, V.; Gehrke, R.; Hanke, F.; et al. Ab initio molecular simulations with numeric atom-centered orbitals. Comput. Phys. Commun. 2009, 180, 2175-96.

45. Lee, C.; Yang, W.; Parr, R. G. Development of the Colle-Salvetti correlation-energy formula into a functional of the electron density. Phys. Rev. B. 1988, 37, 785.

46. Becke, A. D. Density-functional thermochemistry. III. The role of exact exchange. J. Chem. Phys. 1993, 98, 5648-52.

47. Molinari, N.; Mailoa, J. P.; Kozinsky, B. Effect of salt concentration on ion clustering and transport in polymer solid electrolytes: a molecular dynamics study of PEO-LiTFSI. Chem. Mater. 2018, 30, 6298-306.

48. Kang, P.; Wu, L.; Chen, D.; et al. Dynamical ion association and transport properties in PEO-LiTFSI electrolytes: effect of salt concentration. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2022, 126, 4531-42.

49. Brooks, D. J.; Merinov, B. V.; Goddard, W. A.; Kozinsky, B.; Mailoa, J. Atomistic description of ionic diffusion in PEO-LiTFSI: effect of temperature, molecular weight, and ionic concentration. Macromolecules 2018, 51, 8987-95.

50. Darden, T.; York, D.; Pedersen, L. Particle mesh Ewald: an N·log(N) method for Ewald sums in large systems. J. Chem. Phys. 1993, 98, 10089-92.

51. Essmann, U.; Perera, L.; Berkowitz, M. L.; Darden, T.; Lee, H.; Pedersen, L. G. A smooth particle mesh Ewald method. J. Chem. Phys. 1995, 103, 8577-93.

52. Pronk, S.; Páll, S.; Schulz, R.; et al. GROMACS 4.5: a high-throughput and highly parallel open source molecular simulation toolkit. Bioinformatics 2013, 29, 845-54.

53. Brooks, C. L. 3rd.; Case, D. A.; Plimpton, S.; Roux, B.; van der Spoel, D.; Tajkhorshid, E. Classical molecular dynamics. J. Chem. Phys. 2021, 154, 100401.

54. Gouveia, A. S. L.; Bernardes, C. E. S.; Tomé, L. C.; et al. Ionic liquids with anions based on fluorosulfonyl derivatives: from asymmetrical substitutions to a consistent force field model. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2017, 19, 29617-24.

55. Jorgensen, W. L.; Maxwell, D. S.; Tirado-rives, J. Development and testing of the OPLS all-atom force field on conformational energetics and properties of organic liquids. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996, 118, 11225-36.

56. Rizzo, R. C.; Jorgensen, W. L. OPLS all-atom model for amines: resolution of the amine hydration problem. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999, 121, 4827-36.

57. Watkins, E. K.; Jorgensen, W. L. Perfluoroalkanes: conformational analysis and liquid-state properties from ab initio and Monte Carlo calculations. J. Phys. Chem. A. 2001, 105, 4118-25.

58. Brehm, M.; Thomas, M.; Gehrke, S.; Kirchner, B. TRAVIS-a free analyzer for trajectories from molecular simulation. J. Chem. Phys. 2020, 152, 164105.

59. Brehm, M.; Kirchner, B. TRAVIS - a free analyzer and visualizer for Monte Carlo and molecular dynamics trajectories. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2011, 51, 2007-23.

60. Mehrer, H. Diffusion in solids: fundamentals, methods, materials, diffusion-controlled processes, 1th ed.; Springer Berlin, Heidelberg, 2007.

61. Zhou, Z. B.; Matsumoto, H.; Tatsumi, K. Low-melting, low-viscous, hydrophobic ionic liquids: aliphatic quaternary ammonium salts with perfluoroalkyltrifluoroborates. Chemistry 2005, 11, 752-66.

62. Zhou, Z. B.; Matsumoto, H.; Tatsumi, K. Low-melting, low-viscous, hydrophobic ionic liquids: 1-alkyl(alkyl ether)-3-methylimidazolium perfluoroalkyltrifluoroborate. Chemistry 2004, 10, 6581-91.

63. Zhou, Z. B.; Matsumoto, H.; Tatsumi, K. Cyclic quaternary ammonium ionic liquids with perfluoroalkyltrifluoroborates: synthesis, characterization, and properties. Chemistry 2006, 12, 2196-212.

64. Fan, L.; He, H.; Nan, C. Tailoring inorganic-polymer composites for the mass production of solid-state batteries. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2021, 6, 1003-19.

65. Zhang, X.; Cheng, S.; Fu, C.; et al. Advancements and challenges in organic-inorganic composite solid electrolytes for all-solid-state lithium batteries. NanoMicro. Lett. 2024, 17, 2.

66. Ulihin, A. S.; Uvarov, N. F.; Gerasimov, K. B. Conductivity of lithium bis(trifluoromethane)sulfonamide (LiTFSI). 6th. International. Russian-Kazakhstan. Conference. “Chemical. Technologies. of. Functional. Materials”. (RKFM-2020). , Elsevier Ltd., 2020; Vol. 31, pp 523-4.

67. Kotwiński, J.; Marzantowicz, M.; Leszczynska, M.; Gągor, A.; Abrahams, I.; Krok, F. Polymorphism in LiN(CF3SO2)2. Solid. State. Ionics. 2019, 330, 9-16.

68. Lassègues, J. C.; Grondin, J.; Aupetit, C.; Johansson, P. Spectroscopic identification of the lithium ion transporting species in LiTFSI-doped ionic liquids. J. Phys. Chem. A. 2009, 113, 305-14.

69. Pitawala, J.; Martinelli, A.; Johansson, P.; Jacobsson, P.; Matic, A. Coordination and interactions in a Li-salt doped ionic liquid. J. Non-Cryst. Solids. 2015, 407, 318-23.

70. Edman, L. Ion association and ion solvation effects at the crystalline-amorphous phase transition in PEO-LiTFSI. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2000, 104, 7254-8.

71. Rey, I.; Johansson, P.; Lindgren, J.; Lassègues, J. C.; Grondin, J.; Servant, L. Spectroscopic and theoretical study of (CF3SO2)2N-(TFSI-) and (CF3SO2)2NH (HTFSI). J. Phys. Chem. A. 1998, 102, 3249-58.

72. Seo, D. M.; Boyle, P. D.; Sommer, R. D.; Daubert, J. S.; Borodin, O.; Henderson, W. A. Solvate structures and spectroscopic characterization of LiTFSI electrolytes. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2014, 118, 13601-8.

73. Rey, I.; Lassègues, J.; Grondin, J.; Servant, L. Infrared and Raman study of the PEO-LiTFSI polymer electrolyte. Electrochim. Acta. 1998, 43, 1505-10.

74. Han, S.; Sommer, R. D.; Boyle, P. D.; et al. Electrolyte solvation and ionic association: Part IX. Structures and raman spectroscopic characterization of LiFSI solvates. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2022, 169, 110544.

75. Bazylewski, P.; Divigalpitiya, R.; Fanchini, G. In situ Raman spectroscopy distinguishes between reversible and irreversible thiol modifications in L-cysteine. RSC. Adv. 2017, 7, 2964-70.

76. Savoie, B. M.; Webb, M. A.; Miller, T. F. 3rd. Enhancing cation diffusion and suppressing anion diffusion via lewis-acidic polymer electrolytes. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2017, 8, 641-6.

77. Monroe, C.; Newman, J. The impact of elastic deformation on deposition kinetics at lithium/polymer interfaces. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2005, 152, A396.

78. Doyle, M.; Fuller, T. F.; Newman, J. The importance of the lithium ion transference number in lithium/polymer cells. Electrochim. Acta. 1994, 39, 2073-81.

79. Sand, H. J. III. On the concentration at the electrodes in a solution, with special reference to the liberation of hydrogen by electrolysis of a mixture of copper sulphate and sulphuric acid. London. Edinburgh. Dublin. Philos. Mag. J. Sci. 1901, 1, 45-79.

Cite This Article

How to Cite

Download Citation

Export Citation File:

Type of Import

Tips on Downloading Citation

Citation Manager File Format

Type of Import

Direct Import: When the Direct Import option is selected (the default state), a dialogue box will give you the option to Save or Open the downloaded citation data. Choosing Open will either launch your citation manager or give you a choice of applications with which to use the metadata. The Save option saves the file locally for later use.

Indirect Import: When the Indirect Import option is selected, the metadata is displayed and may be copied and pasted as needed.

About This Article

Copyright

Data & Comments

Data

Comments

Comments must be written in English. Spam, offensive content, impersonation, and private information will not be permitted. If any comment is reported and identified as inappropriate content by OAE staff, the comment will be removed without notice. If you have any queries or need any help, please contact us at support@oaepublish.com.