Photoredox-catalyzed reduction of unsaturated compounds using water as the hydrogen source

Abstract

Reduction of unsaturated compounds is a practical approach for functional group modification in organic synthesis. Water, as a readily obtainable, economical, and environmentally friendly reagent, has the potential to act as a hydrogen source in reduction reactions. Since water is difficult to serve as a reductant itself, photocatalysis has been explored to provide milder conditions for electron donation. This review concentrates on advances in photoredox-catalyzed H2O-incorporated reductive addition reactions of unsaturated bonds, with water acting as a hydrogen source. Typical mechanisms of water activation and utilization are discussed by categorizing strategies into coordination activation, oxidative addition activation, and indirect activation of water by substrate activation. The mechanistic view provides descriptions of current challenges and prospects for future explorations.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

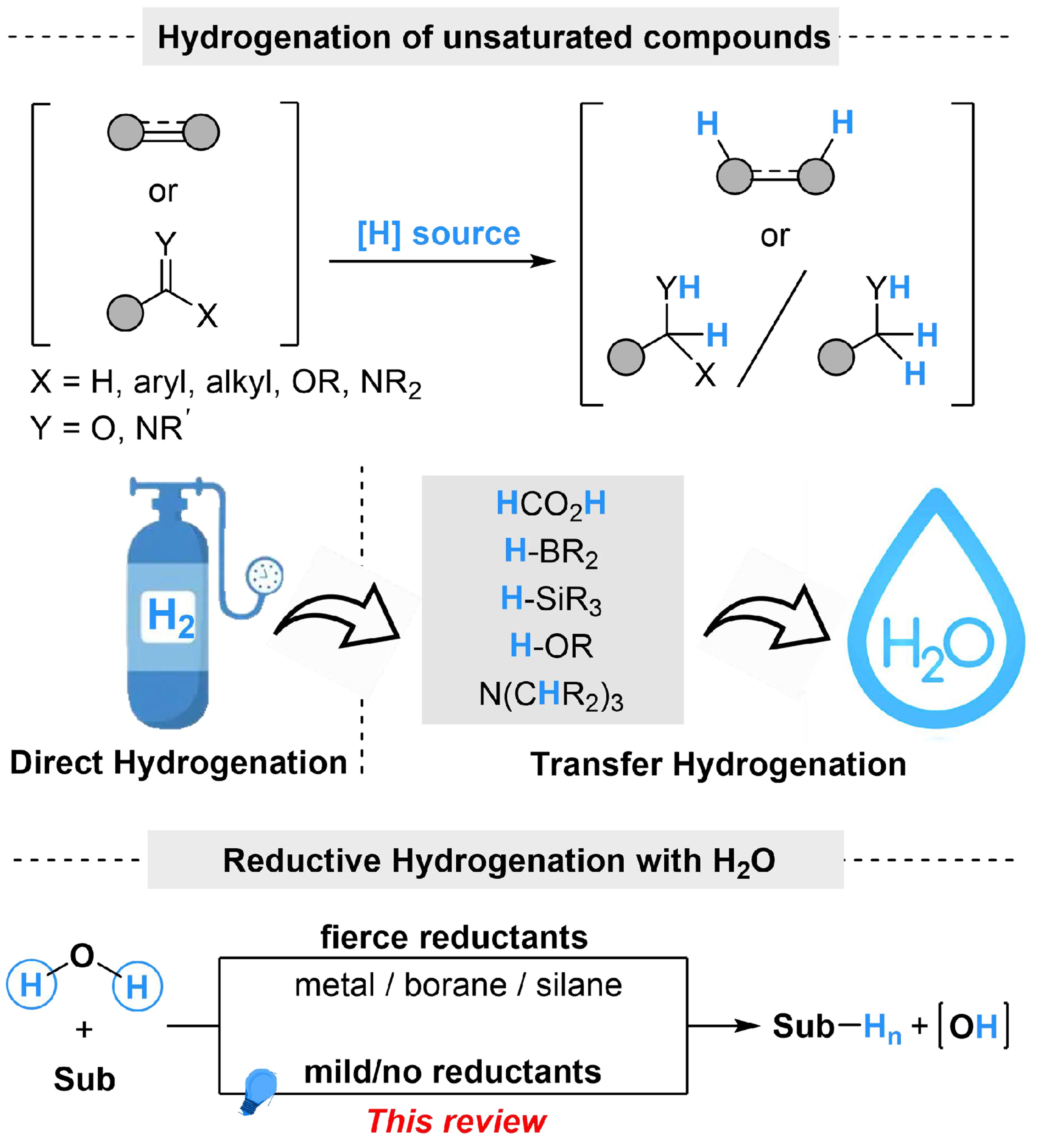

Reduction of unsaturated compounds is a practical method in organic synthesis, widely applied in production of materials, agrochemicals, and pharmaceuticals[1-7]. The most common methods for reduction of unsaturated compounds are direct hydrogenation with H2 gas and transition metal as catalysts, featuring high atomic economy and industrial value[8-16]. Despite benefitting from these advantages, direct hydrogenation suffers from difficulties in regulating the chemo-selectivity in the presence of other unsaturated groups, as well as potential danger of explosion and complicated experimental setups due to the use of an explosive gas. Therefore, catalytic transfer hydrogenation strategies have been developed to optimize the chemo-selectivity and eliminate the potential danger. Several organic reductants have been employed as the sacrificial reagents[4], such as formic acid[17-24], alcohols[19-21], amines[25,26], boranes[27-29], silanes[29,30], and thiophenol[31], while presenting as a hydrogen source to realize transfer hydrogenation. Compared to methods using hydrogen gas, most transfer hydrogenation reactions are homogeneous, showing high efficiency and convenience in reactor design, making them more suitable for the synthesis of fine chemicals. Water, as a readily obtainable reagent, is an economical and environmentally friendly hydrogen source, presenting great potential in hydrogenation reactions[32-40]. Compared with hydrogen gas and organic reductants, water could be considered as a “zero cost” reagent with greater economic value. In addition, the utilization of hydrogen from water features potential in reductive deuterating reactions, since deuterium water is more available than deuterium gas or multi-deuterated organic reductants [Scheme 1].

Although strategies for utilization of water as a hydrogen source in reductive systems have been studied and developed, sacrificial reductants are necessary to donate electrons, since water is difficult to act as a reductant itself. The sacrificial reductants (such as metal, borane and silane) are initially introduced to realize the reaction through direct activation of water[32-36,41-49] or indirect electron donation[50-58], which leads to issues with functional group tolerance and ease of application. Considering environmental friendliness, photocatalysis has been studied during the past decades, which avoids the use of sensitive agents and employs facile organic reductants instead, providing a milder strategy for electron donation in reductive reaction systems[59-63].

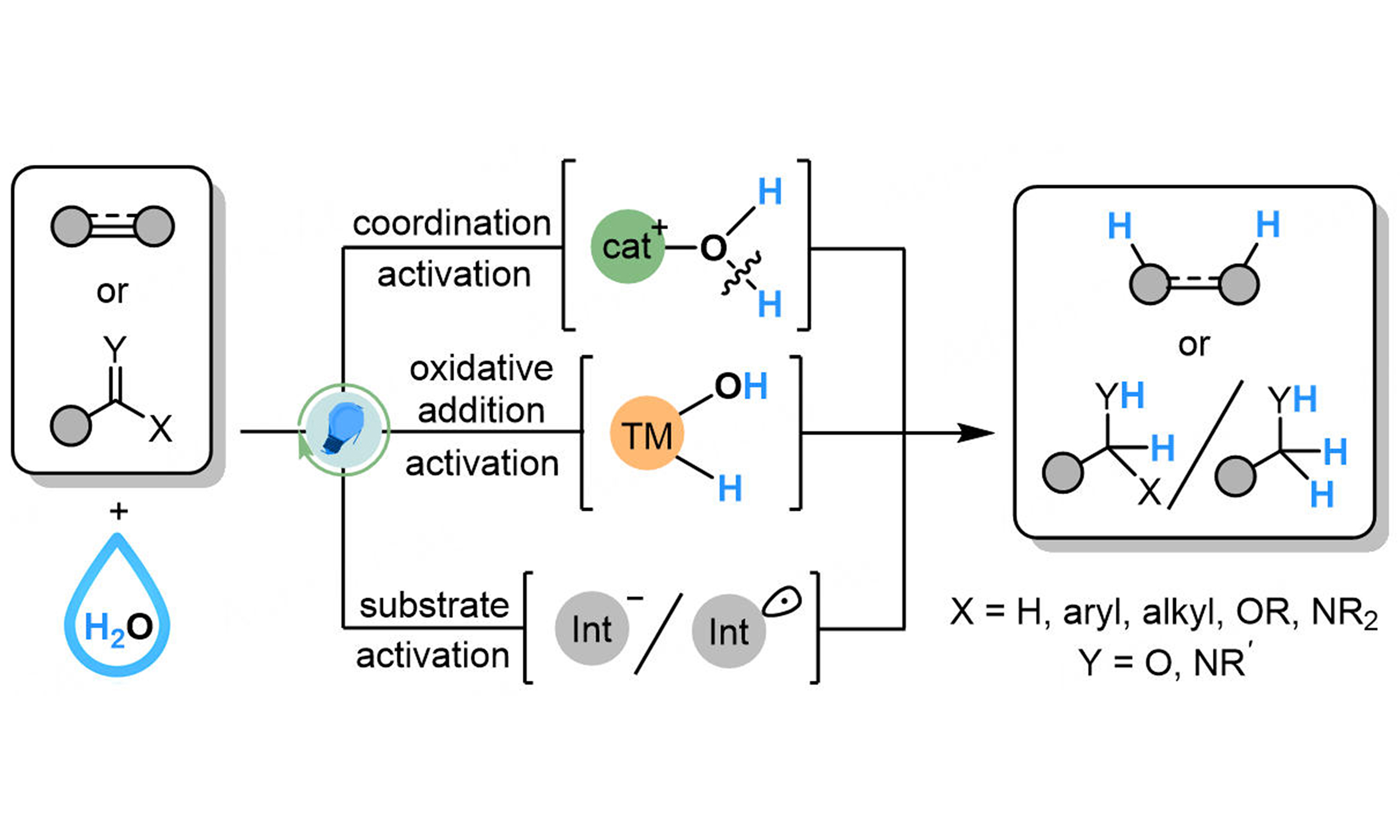

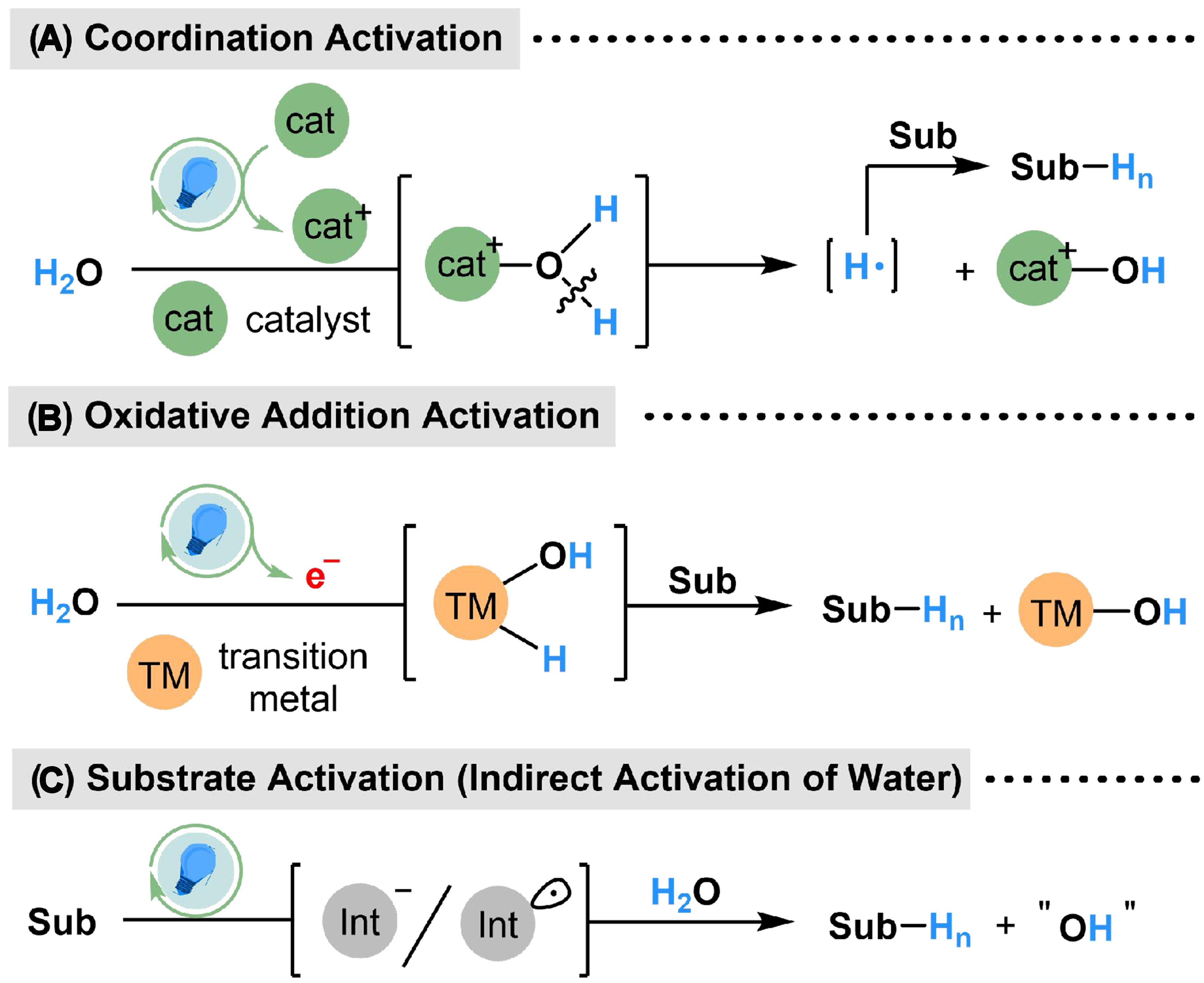

Several strategies have been developed to produce and apply the in situ generated “H” species from water in organic synthesis. The typical mechanism on photocatalyzed water activation and utilization could be categorized into three types of pathways. (i) Coordination activation. Single electron transfer (SET) is the most common process in photoredox catalysis; with the presence of catalysts that are prone to losing electrons, electrophilic intermediates with empty d or p orbitals are easy to generate from the photoredox cycle (such as cations, radical cations or free hole in a semiconductor). The homolytic cleavage of the O–H bond [bond dissociation energy (BDE) = 118.0 kcal·mol-1][64,65] in H2O could be induced by coordination-induced bond weakening, through the coordination from H2O to the electrophilic center in catalysts, followed by interaction with substrates to complete the hydrogenated reactions [Scheme 2A]; (ii) Oxidative addition activation. The photoredox cycle could act as a milder electron donator, passing electrons from the sacrificial reductants to catalytic cycle of transition metal complexes. The produced electron would turn the transition metal into a lower oxidation state, which facilitates the oxidative addition with water on the transition metal center, and the generated metal–hydride (M–H) bond is capable of further insertion to unsaturated functional groups to realize reductive hydrogenation. A stable metal–oxygen (M–O) bond is also formed in this process, while electrons from the photoredox cycle could also break the M–O bond and complete the catalytical cycle in a facile way [Scheme 2B]; (iii) Indirect activation of water by substrate activation. The photoredox cycle on substrate activation has been widely reported, in which the substrates could be transformed into carbanion or radical intermediate. Meanwhile, the ionization equilibrium of H2O might provide protons, which could directly react with the activated substrates or undergo an indirect delivery process to hydrogenation of substrates [Scheme 2C].

This review focuses on the advances in photocatalyzed H2O-incorporated reduction of unsaturated compounds, where H2O acts as a hydrogen source under mild conditions; the following discussions would base on the three models in Scheme 2 including: (1) Photocatalyzed hydrogenation of unsaturated compounds by coordination activation of H2O; (2) Photocatalyzed hydrogenation of unsaturated bonds by activation of H2O through oxidative addition; (3) Photocatalyzed hydrogenation of unsaturated bonds with H2O through substrate activation.

PHOTOCATALYZED HYDROGENATION OF UNSATURATED COMPOUNDS BY COORDINATION ACTIVATION OF H2O

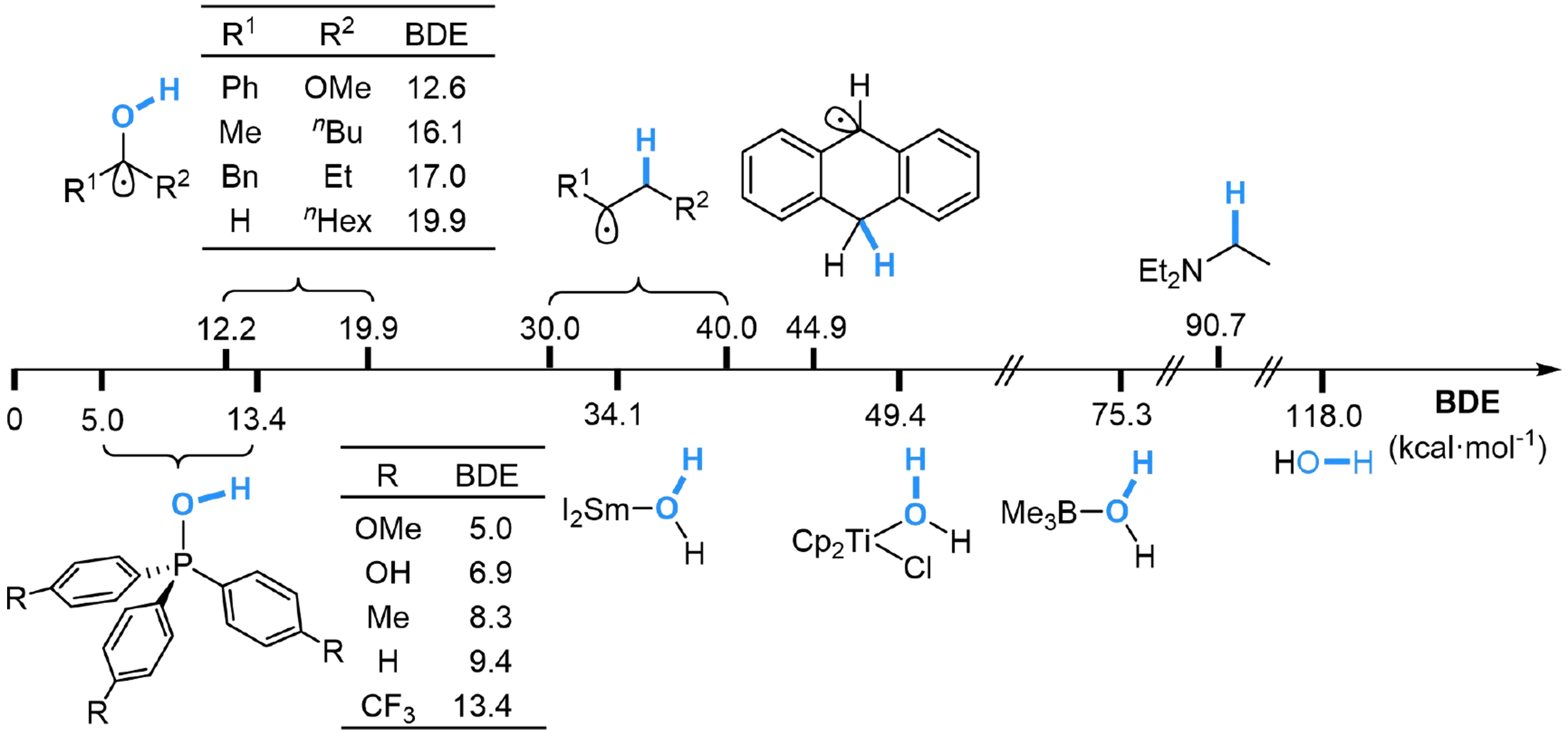

Photocatalyzed reduction of alkene/aldehyde/ketone/imine/nitrobenzene/arene with H2O activated by electron-deficient species

Elements with empty d or p orbitals are capable of H2O activation through coordination activation, such as samarium[33,48,66-69], titanium[37,70,71], bismuth[35], borane[32,34,72] and phosphorus[40] compounds, enabling the homolytic O–H bond cleavage to provide a reductive hydrogen atom for further conversions. The order of BDE reveals the possible application of these water adducts in hydrogenation of vinyl groups, carbonyl groups and dearomatized reactions [Scheme 3].

In 1991, Pandey et al. suggested that the capability of heterolytic O–H bond cleavage in [R3P-OH] radical is thermodynamically driven by the strong P=O bond in phosphine oxides[73]. The BDE of O–H bond in [R3P-OH] radical (5.0-13.4 kcal·mol-1) is much lower than the energy for hydrogen radical addition to vinyl groups (30-40 kcal·mol-1) or aromatic π systems (40-50 kcal·mol-1), which is utilized by Zhang et al. in hydrogenation of carbon-carbon unsaturated systems, using Ir[dF(CF3)ppy]2(dtbbpy)PF6 (dF(CF3)ppy, 2-(2,4-difluorophenyl)-5-trifluoromethyl-pyridine; dtbbpy, 4,4’-di-tert-butyl-2,2’-bipyridine) as photocatalyst[40]. Both aliphatic and aromatic alkenes could be hydrogenated smoothly by this method, where carbonyl group, hydroxyl group, amide, halogen, and heteroaromatic rings are well-tolerated. Naphthalene and its derivatives are also suitable in this reaction to afford tetrahydronaphthalene, where electron-deficient arene ring performs better chemoselectivity. Moreover, several indole derivatives could be constructed using the corresponding quinoline derivatives as the reactants, realizing a reductive ring contraction through radical hydrogenative rearrangement. The reaction is initiated by photocatalyzed SET from Ar3P to *IrIII at the excited state, forming radical cation Ar3P·+, which could accept nucleophilic addition from H2O to generate Int-4a, then deprotonated by another molecular Ar3P to afford [Ar3P-OH] radical Int-4b. The alkene could undergo hydrogen atom transfer (HAT) with Int-4b and generate Int-4c, while POAr3 is released from the reaction. Alkane is obtained by another HAT process between Int-4c and thiophenol, in which the thiophenol radical [Ar’S·] could undergo SET with IrII and capture proton to regenerate thiophenol. Meanwhile, thiophenol in this system experiences a proton exchange with H2O to reach a fast equilibrium [Scheme 4].

Scheme 4. Phosphine-mediated H2O activation for radical hydrogenation of inactivated alkenes and arenes.

The photocatalyzed Ir/Ph3P/H2O also shows potential for the reduction of carbonyl groups, as recently realized by our group, through the adjustment of phosphorus-based reductants and HAT reagents[74]. The reaction initiates with a similar process to generate the key intermediate Int-5a, followed by deprotonation to form [Ph3P-OH] radical Int-5b. The carbonyl substrate could abstract hydrogen atoms from Int-5b to afford Int-5c, which could accept another hydrogen atom from thiophenol to produce the target product. Both aliphatic and aromatic carbonyl compounds, along with imines, are suitable for this transformation, where aromatic substrates present better reactivity. In the absence of thiophenol as the HAT reagent, the accumulating Int-5c would undergo homo-coupling reaction to produce pinacols as the terminal product, where aromatic aldehydes and ketones are both applicable [Scheme 5].

The Ir/Ar3P/H2O system exhibits similar reactivity when acetic acid is introduced instead of thiophenol, as discovered by Xie et al., to realize hydrogenation of activated alkenes[75]. Several vinyl pyridines with alkyl and aryl substituents were tolerated in this reaction, while N-phenylacrylamides also underwent transfer hydrogenation smoothly. The [Ph3P-OH] radical still acts as the key intermediate in this reaction, then undergoes HAT with activated alkenes to generate Int-6a and POPh3. The Int-6a is easily protonated and reduced by SET with IrII, followed by an acid-assisted proton exchange to produce the hydrogenated products [Scheme 6].

Thioxanthone-trifluoromethanesulfonic acid complex (9-HTXTF) is also capable of photocatalyzed activation of PPh3, which has been established by Kang et al., transforming several α,β-unsaturated amides, esters and ketones into the corresponding hydrogenated products[76]. In the presence of trifluoromethanesulfonic acid (TfOH), the protonated substrate could undergo SET with 9-HTXTF·- to form Int-7a, which is protonated by H2O in the coordination of Ph3P·+ to generate [Ph3P-OH] radical and Int-7b. The [Ph3P-OH] radical might undergo a rapid disproportion to produce PPh3, H2O and POPh3, while the Int-7b undergoes another SET with 9-HTXTF·- and protonation to give the target products [Scheme 7].

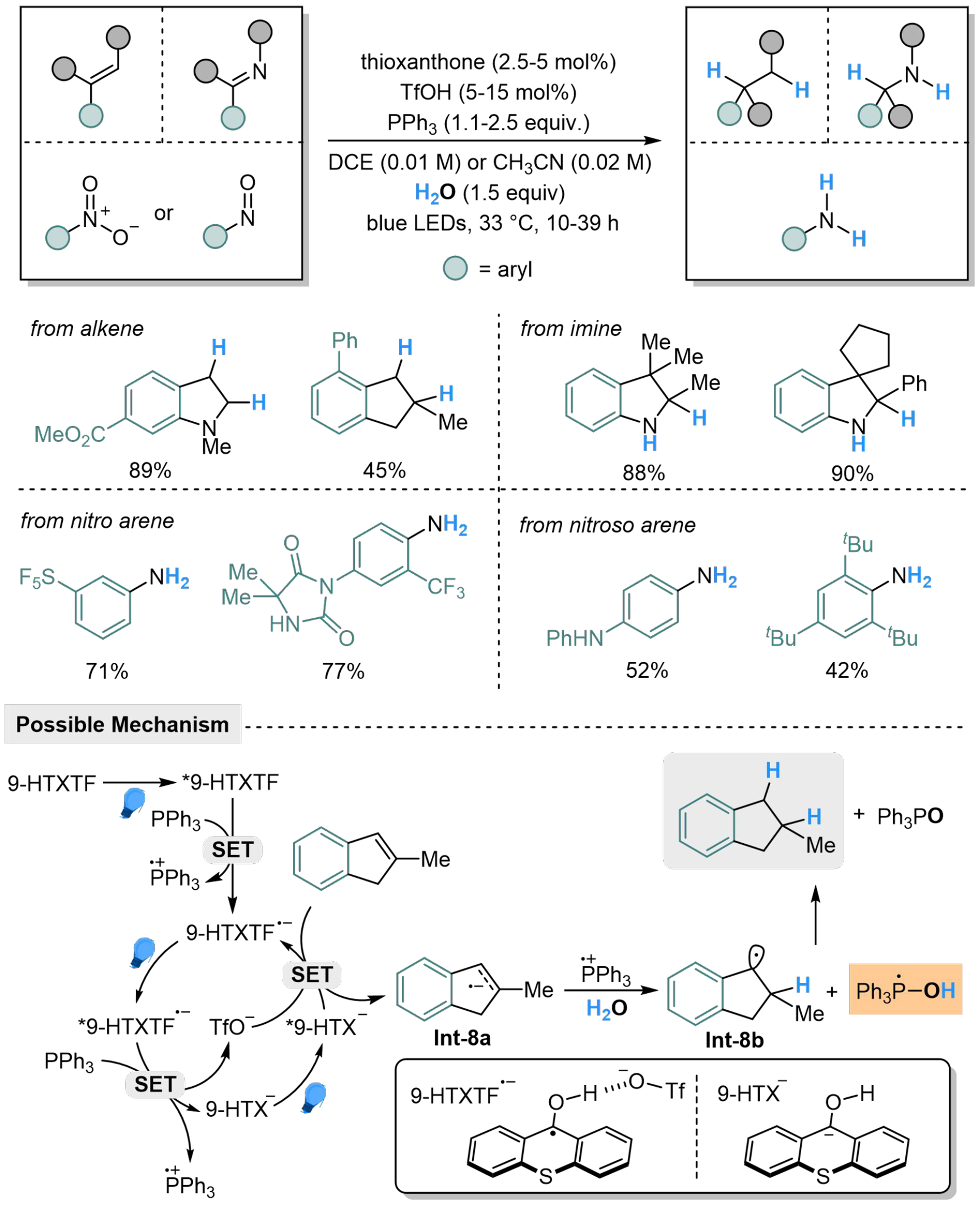

The substrate scope of the 9-HTXTF/Ar3P/H2O is then expanded to aryl alkenes, aryl imines, nitro arenes and nitroso arenes, providing access to aliphatic motifs, primary and secondary aryl amines respectively[77]. During the further exploration of the mechanism, the 9-HTXTF·- is found to be capable of being activated by light irradiation, followed by another SET with PPh3 to form 9-HTX- and Ph3P·+. The 9-HTX- is also photosensitive, which undergoes a consecutive photocatalyzed electron transfer (ConPET) with substrates to regenerate 9-HTXTF·- and produce Int-8a. The Int-8a is then protonated by H2O in coordination to give Int-8b and [Ph3P-OH] radical, where the following HAT process produces POPh3 and the hydrogenated product [Scheme 8].

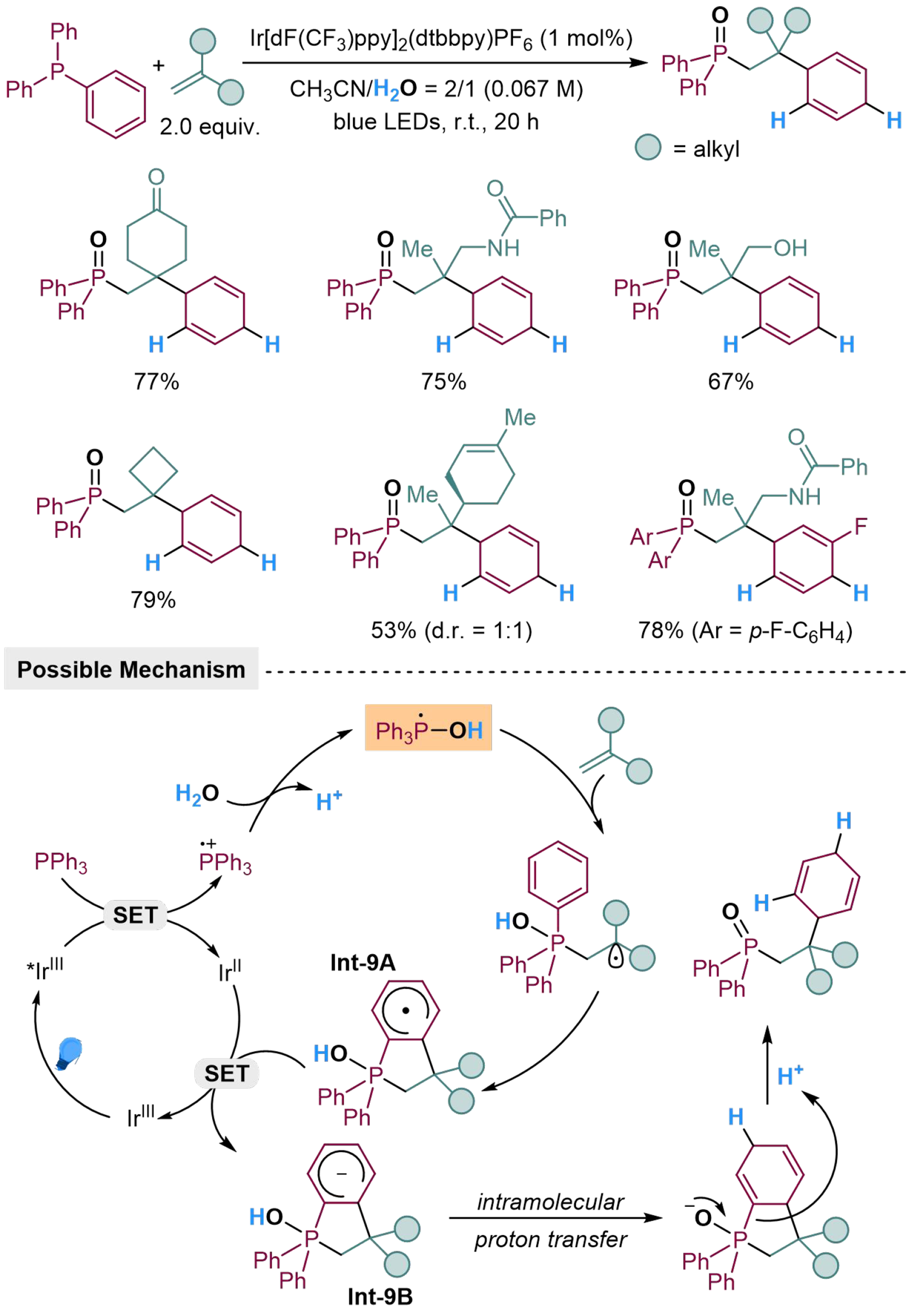

Dearomatized hydrogenation of (hetero)arenes also serves as an essential reduction in organic synthesis, providing strategies for constructing complex unsaturated rings; however, this remains a challenge due to the chemical stability of aromatic substrates[78]. The Birch reduction provides a protocol to unconjugated 1,4-cyclohexadienes from arenes traditionally, which focuses on utilizing pyrophoric alkali metals. Thus, it results in harsh experimental procedures, bringing problems on functional group tolerance and scale-up applications[79-83]. During the past decades, facile strategies have been explored to improve the dearomatized reactions, by the replacement of milder metal-based reductants[84-89], or the employment of transition-metal-based catalysts through M-H pathways[90-97]. The Birch-type dearomatization could also be realized by photocatalyzed dearomatizing three-component coupling of arylphosphines, alkenes, and H2O, through intramolecular carbocyclization[98]. The reaction is initiated by photocatalyzed SET from Ph3P to *IrIII at the excited state, forming radical cation Ph3P·+, which could accept nucleophilic addition and then deprotonated to afford [Ph3P-OH] radical. The [Ph3P-OH] radical could perform not only as a hydrogen atom donor, but also as a phosphorus source by radical addition to gem-disubstituted alkene, followed by a 5-endo-trig cyclization to generate a cyclohexadienyl radical Int-9A. The Int-9A would undergo SET with IrII to form carbanion Int-9B and regenerate IrIII. Subsequently, intramolecular proton transfer and further protonation of Int-9B would produce the corresponding product with a new C(sp2)–H bond and a new C(sp3)–H bond [Scheme 9]. Terminal alkenes with carbonyl, hydroxyl, and amino groups are well-tolerated in this reaction, while terminal alkene features obvious chemoselectivity in the presence of internal alkene moiety.

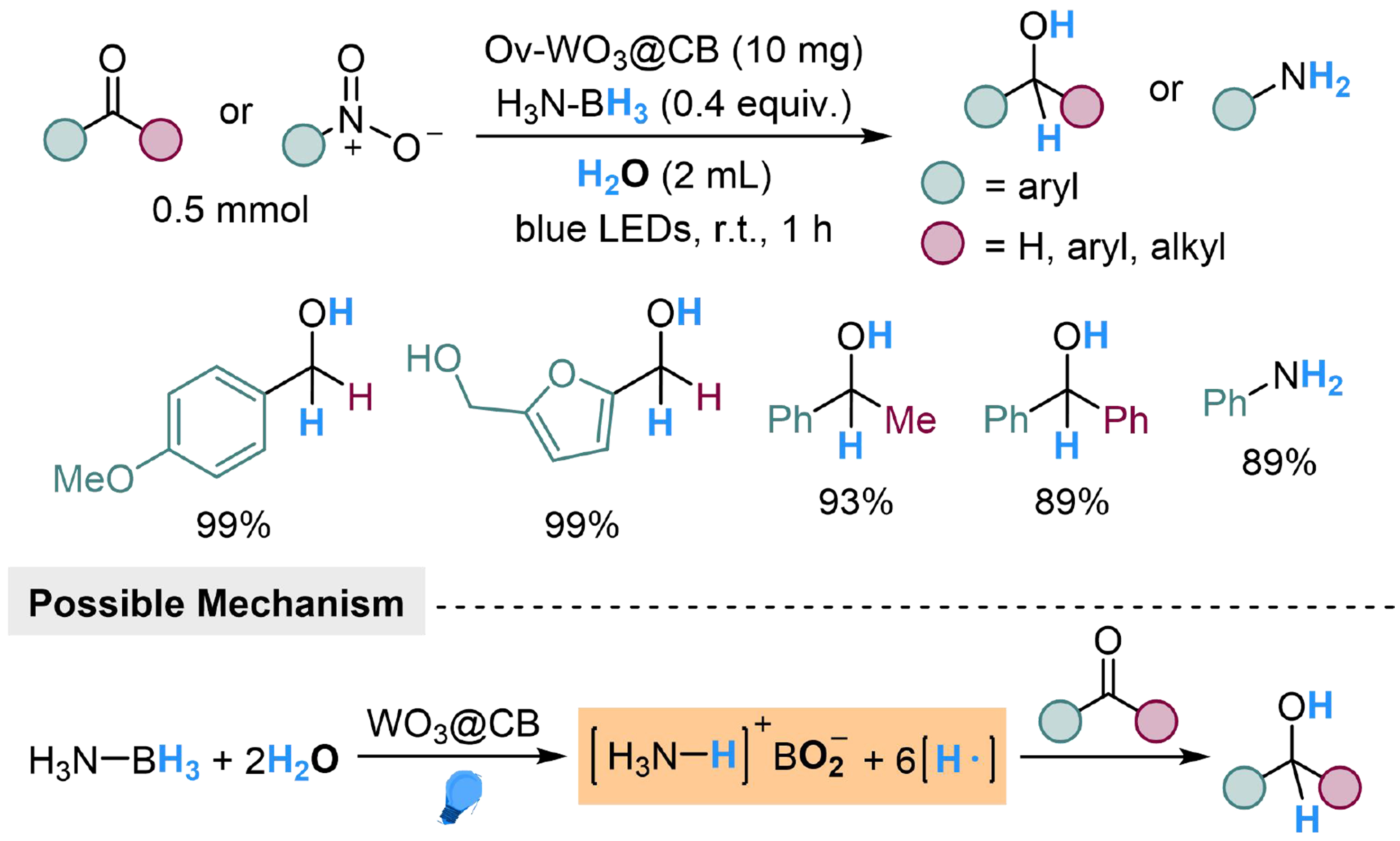

Since the oxygen in H2O showed a strong coordination tendency to boron, the hydrogen in H2O could also transform into a hydrogen atom in the presence of ammonia borane, which was realized by Meng et al., using the Ov-WO3@CB catalyst prepared by anchoring cucurbit[5]uril on oxygen vacancy-rich WO3[99]. The ammonia borane and H2O molecules tended to be absorbed and activated on the W-catalyst to provide hydrogen radicals, which then underwent addition to unsaturated groups to realize hydrogenation. Several aryl aldehydes and ketones were converted into the corresponding alcohols by this method, while nitrobenzene derivates were transformed into anilines [Scheme 10].

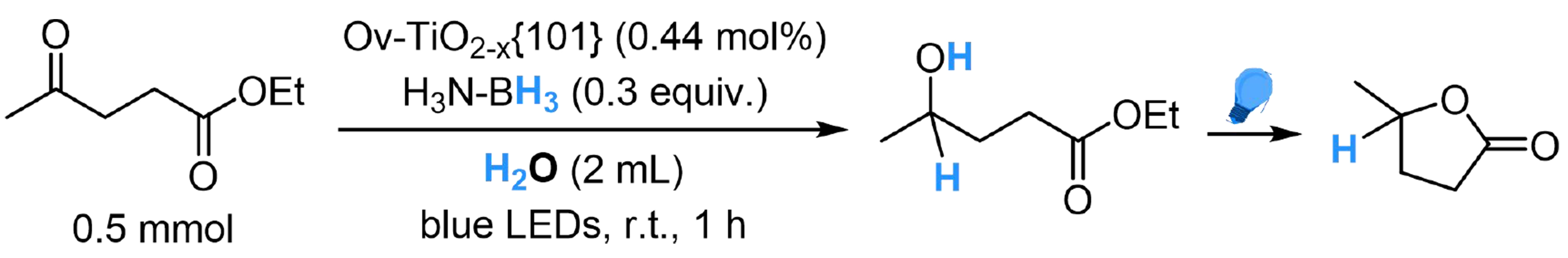

A similar strategy was also successful in the ethyl levulinate (EL) to γ-valerolactone (GVL) transformation through hydrogenation and photocatalyzed cyclization[100]. The TiO2-base catalyst Ov-TiO2-x{101} catalyst showed efficiency in activating ammonia borane and H2O and great reusability, providing an effective way for reductive upgrading of biomass feedstocks [Scheme 11].

Photocatalyzed reduction of alkene/aldehyde/ketone/imine with H2O activated by photoexcited semiconductor

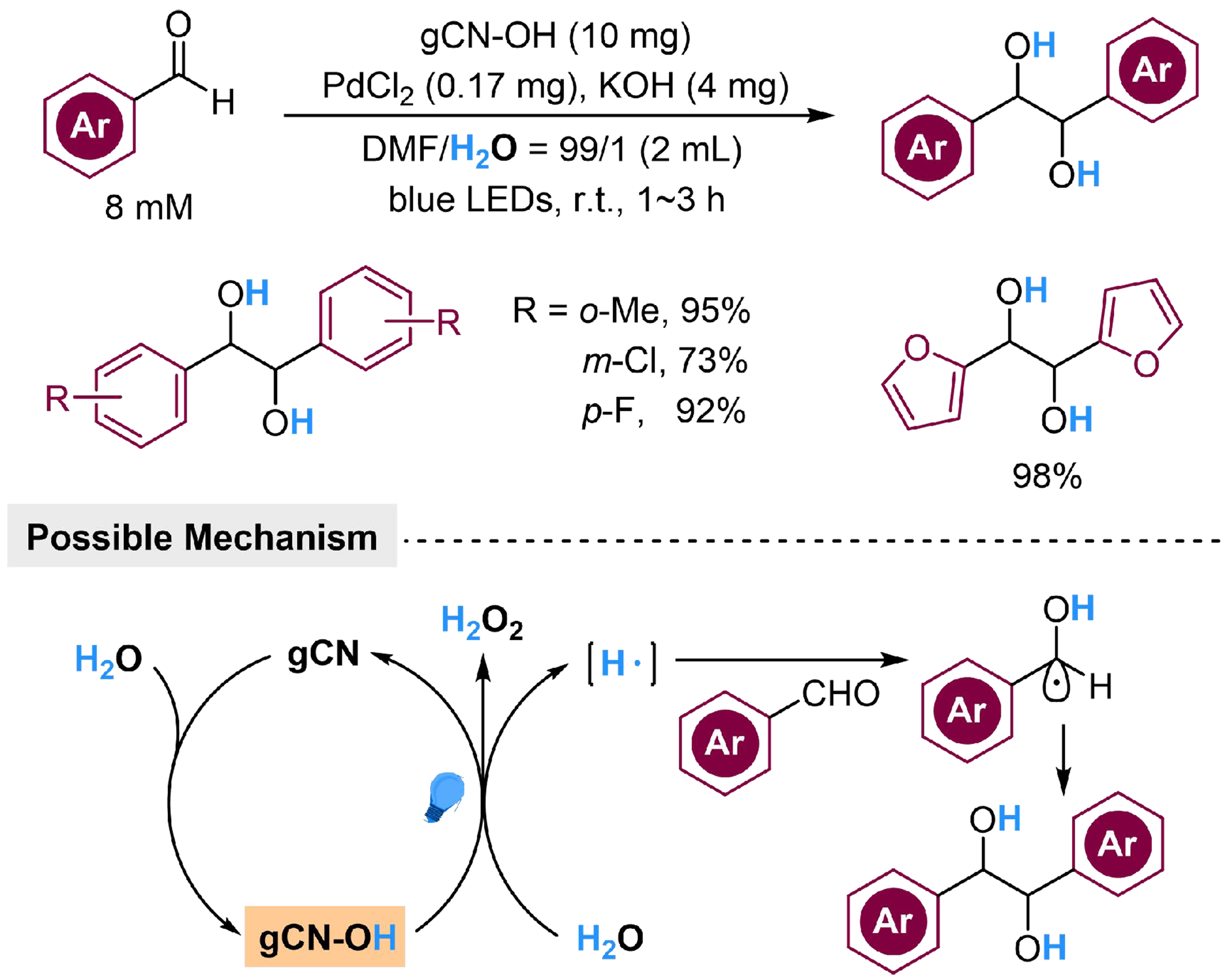

With the development of photocatalysis, previous investigations confirm that hydrogen gas could be produced by splitting water in the presence of graphitic carbon nitride (gCN), which is a semiconductor with suitable bandgap and thermal/chemical stability in photocatalytic H2 generation[101-104]. However, to connect the H2 generation reaction with hydrogenation of unsaturated organic molecules in series, additional catalysts for H2 activation are necessary, bringing difficulties in the catalyst design. In contrast, the in situ utilization of the abstracted hydrogen from H2O in hydrogenated reactions is more efficient. During the past decades, gCN is found to be capable of turning alcohols into hydrogen donor, while the catalytic performance could be further tuned by modification of the supported metal on gCN as cocatalyst[105,106]. Since H2O shares a structural similarity with alcohols, Zhang et al. have designed a hydroxylated gCN (gCN-OH) catalyst to induce the abstraction of hydrogen atom from H2O without introducing sacrificial reductants, which has been employed to realize the reductive coupling reaction of benzaldehydes [Scheme 12][107]. The presence of gCN-OH initiates H2O dissociation under visible light irradiation, releasing hydrogen atom to undergo radical addition to benzaldehyde, and follows by a radical coupling reaction to generate pinacol derivatives. The OH group from H2O dissociating together with the OH from gCN-OH, could recombine into H2O2 and form gCN, which could be hydroxylated by H2O to complete the catalytic cycle. This strategy successfully turns H2O into a reductant in organic synthesis, featuring potential in the replacement of other organic reductants with H2O. Although the by-product H2O2 might interrupt reductive reactions or reduce the functional group tolerance, simultaneous isolation or utilization of H2O2 might stimulate further applications.

Scheme 12. Hydroxylated gCN mediated reductive coupling of benzaldehyde derivatives with H2O. gCN: Graphitic carbon nitride.

The substrate scope of this strategy could be broadened from benzophenone derivatives to various unsaturated bonds by regulating the semiconductor. Han et al. employed defective ultrathin ZnIn2S4 nanosheets (D-ZIS) with abundant S vacancies to realize reductive deuteration of carbonyl compounds, alkenes and imines using D2O as the deuterium source and Na2SO3 as reductant[108]. Ketones would be converted into the corresponding deuterated alcohols; in comparison, aryl aldehydes underwent reductive coupling reaction to generate pinacols as products. In this reaction, the oxygen of D2O was transmitted to Na2SO3 indirectly, through the photocatalyzed catalytical cycle with D-ZIS semiconductor, to generate deuterium atom species. The deuterium radical would react with substrate immediately, followed by addition of another deuterium atom or homo-coupling reaction to produce different products [Scheme 13].

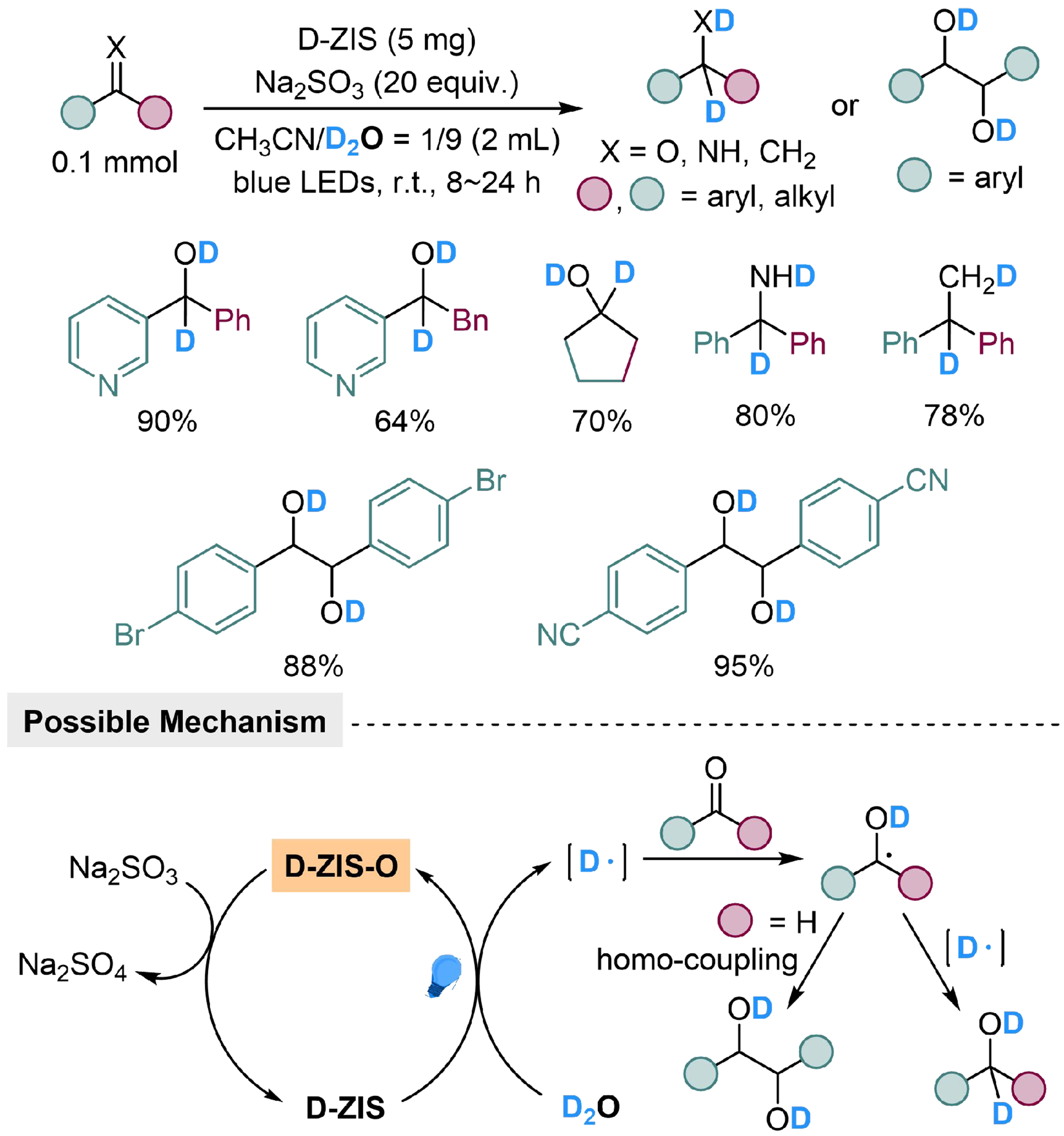

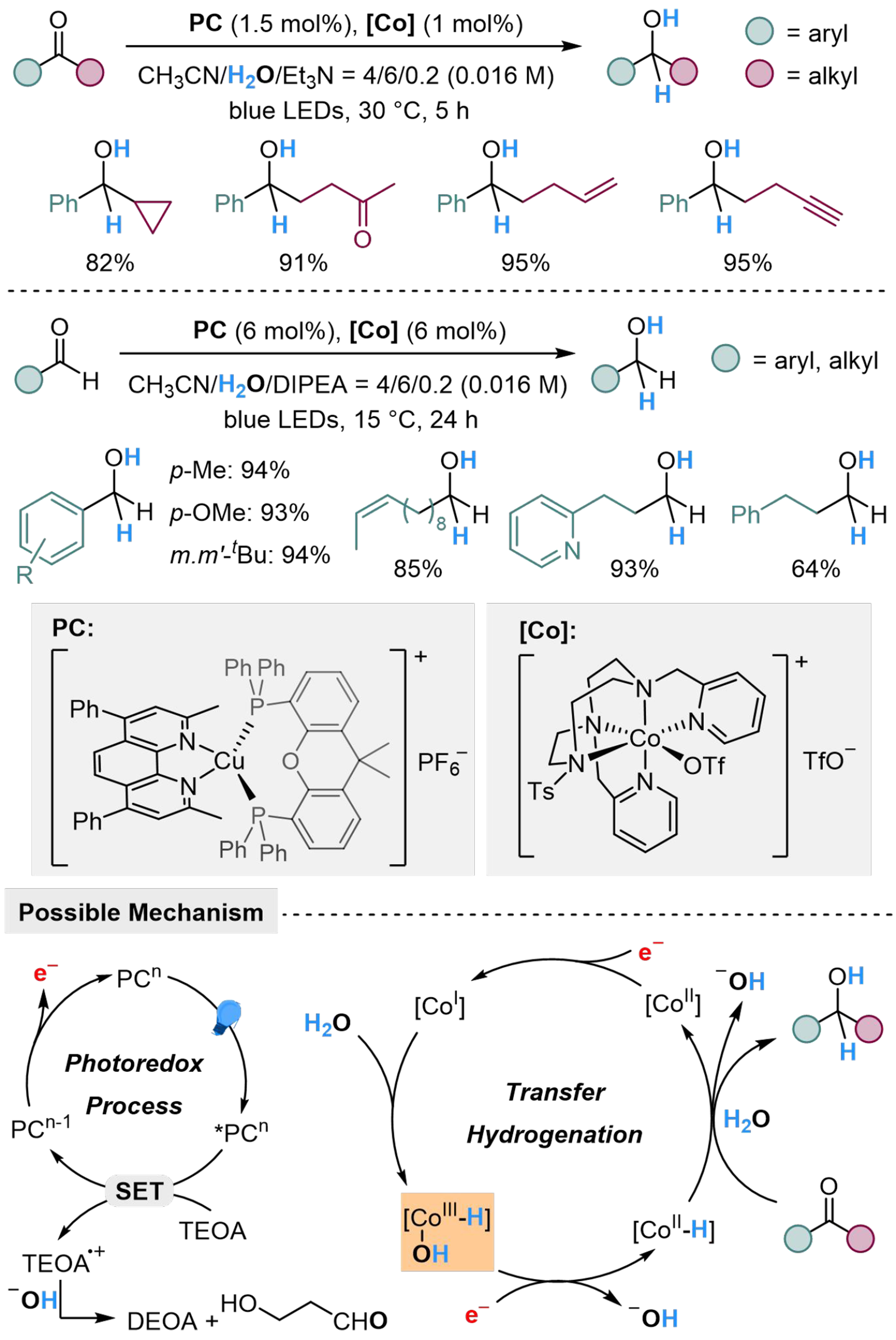

Application on the late-stage functionalization through coordination activation of water

The coordination activation strategies have been applied to the late-stage functionalization of unsaturated compounds using H2O/D2O as the hydrogen/deuterium source. For example, aripiprazole (an antipsychotic drug) could be synthesized from commercial available dehydroaripiprazole through hydrogenation of the C=C double bond, while dihydrofinasteride could be smoothly attained using the same method[76]. The β-cholesterol derivatives could also be hydrogenated or deuterated in a high chemoselectivity[109]. In addition, chiral benzocaine analogs could be obtained by deoxygenative hydrogenation with H2O of the corresponding nitroaromatic substrate and subsequent amino alkylation. Medicinally interesting benzocaine analogs are available by modifying 4-nitrobenzoic acid with menthol motifs, while the late-stage hydrogenation of nilutamide (antiandrogen drug) is also successful[77] [Scheme 14]. The above examples indicate the potential for modification and deuterium labeling of drugs and bioactive molecules by coordination activation of water.

PHOTOCATALYZED HYDROGENATION OF UNSATURATED COMPOUNDS BY ACTIVATION OF H2O THROUGH OXIDATIVE ADDITION

Apart from producing electrophiles to activate H2O in reductive reactions, the photoredox cycle also can pass electrons from sacrificial reductants to center of transition metal catalysts, to facilitate the oxidative addition from water to transition metal and produce a reductive M–H bond for the reduction of unsaturated compounds.

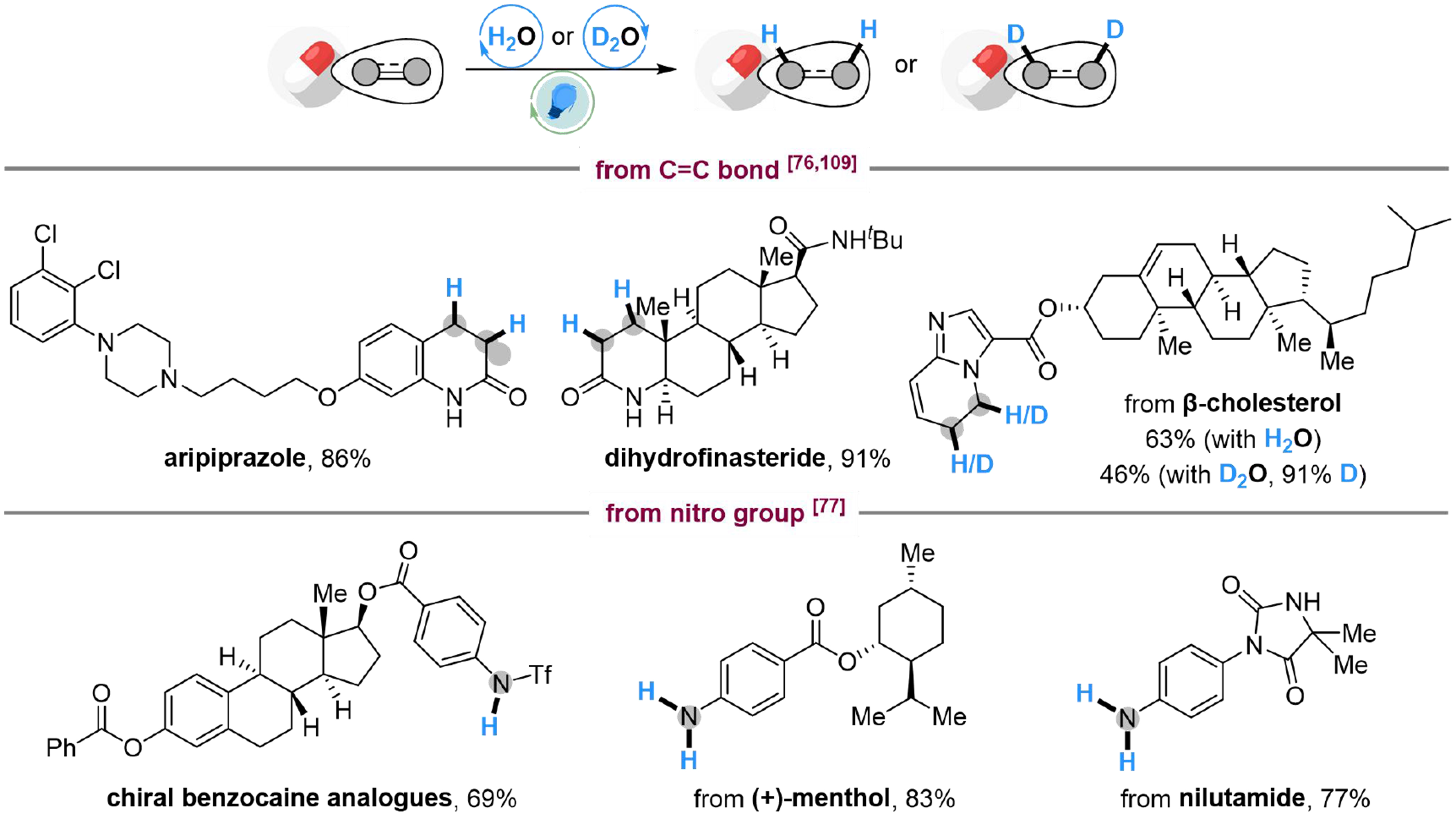

The M–H strategy could be applied in reduction of electrophilic carbonyl groups. Call et al. present a method for reduction of aromatic ketones, both aliphatic and aromatic aldehydes, to the corresponding alcohols, using dual Cu/Co photocatalysis with H2O as a hydride donor[110]. Cyclopropyl group, vinyl group, alkynyl group and aliphatic ketone could be tolerated in this condition. The copper-based catalyst, as a photosensitizer, cooperates with organic amines to provide electrons indirectly under irradiation. The released electron might initially reduce [CoII] to [CoI], which could extract hydrogen from H2O to form a [CoIII–H] bond. After a further reduction from [CoIII–H] to [CoII–H], the nucleophilic insertion to carbonyl groups leads to a hydrogenation result. Nevertheless, for ketones and aldehydes with similar redox potential with the photosensitizer, the formation of ketyl radical anion could be observed, suggesting the possibility of a radical pathway [Scheme 15]. The mechanism studies do not provide enough evidence for the discrimination between interceptions of the ketyl radical anions via HAT with [Co-H] species, and direct reduction via classical hydride transfer pathway.

Our group developed a 2,4,5,6-tetra(9H-carbazol-9-yl) isophthalonitrile (4CzIPN)/Ni-dual catalyzed system to realized Z-selective semi-reduction of alkynes with H2O[111]. A range of Z-aryl alkenes and Z-vinyl silanes could be produced with high regioselectivity, while the amino group, hydroxyl group, and heteroarenes are well-tolerant in this condition. The reaction initiates by photocatalyzed SET from diisopropylethylamine (DIPEA) to 4CzIPN* at an excited state, forming radical anion 4CzIPN·-, which reduced Ni(II) to Ni(0) by delivering electrons. Carbonic acid is reversibly generated from H2O and CO2, which undergoes oxidative addition with Ni(0) and affords Int-16A, where 4,4’-di-tert-butyl-2,2’-bipyridine (4,4’-dtbbpy) is employed as ligand. The carbon-carbon triple bond then coordinates to the Ni(II) center in Int-16A, followed by insertion to Ni–H bond and generated Int-16B, which is then reversibly converted into Int-16C with lower steric repulsion and better thermodynamic stability. Int-16C could be quenched by carbonic acid to afford

Scheme 16. 4CzIPN/Ni-dual catalyzed semi-reduction of alkynes with H2O. 4CzIPN: 2,4,5,6-tetra(9H-carbazol-9-yl) isophthalonitrile.

Although a few studies on photoredox/transition-metal dual-catalyzed reduction of unsaturated bonds have been established, limitations for further exploration remain. First, the in situ generated M–H bond should be relatively stable to prevent direct quenching by H2O before it can attack the substrates, which restricts the reactivity of the M–H bond, presenting challenges in the reduction of relatively inert unsaturated functional groups. Second, organic amines are required as sacrificial reductants to complete the redox cycle, which might release protons and disarray the source of hydrogen in products. The exploration of appropriate metal complex to control the chemo-selectivity and regio-selectivity might provide potential in further applications, while the discovery of reductants that do not release protons might contribute to a higher deuterium rate in the deuterium application with D2O.

PHOTOCATALYZED HYDROGENATION OF UNSATURATED COMPOUNDS WITH H2O THROUGH SUBSTRATE ACTIVATION

Although a few methods have been established to realize photocatalyzed activation of H2O, direct activation of H2O for hydrogenated reactions remains a tough issue, especially in the absence of metallic catalysts and sacrificial reductants. To broaden the utilization of hydrogen from H2O, indirect methodologies have also been developed by utilizing the proton from spontaneous ionization of H2O. The dissociated protons could be delivered to the substrates through direct protonation of negative intermediates or other indirect conversions.

Reduction of carboxylic acid by activation to a hydrogen atom acceptor

Besides direct activation of H2O as a hydrogen donor, the hydrogen in H2O could also undergo proton exchange with thiophenol and be delivered to the activated substrates indirectly. Zhang et al. developed a radical deoxygenated deuteration of carboxylic acids with D2O as an indirect deuterium source, enabled by synergistic thiol catalysis and phosphoranyl radical chemistry [Scheme 17][112]. The reaction is initiated by photocatalyzed SET process from Ph3P to *IrIII, forming radical cation Ph3P·+, which could be attacked by carboxylate and furnish Int-17A. Thermodynamically driven by the formation and release of POPh3, Int-17A could transform into a reactive acyl radical. The proton of thiophenol in this reaction could exchange with excess D2O to generate deuterium-labeled thiophenol, as the deuterium donor, and undergoes HAT with the acyl radical to produce deuterated benzaldehydes. Both aryl and aliphatic carboxylic acids are suitable for this method, while several unsaturated groups, halogen, amino and hydroxyl groups with active hydrogen, are tolerant. Moreover, substrates with cyclopropyl group at α-position could be converted into the corresponding aldehydes in moderate yield, displaying the high efficiency of thiophenol in HAT process.

Reduction of alkene/arene/ketone/ester/carboxylic acid by activation to proton acceptors (carbanion)

The proton from H2O could also participate in hydro-functionalization of C=C double bonds, by activating the substrate to carbanion, as a proton acceptor. Ramirez et al. have described a photocatalyzed oxygen-free hydroalkylation/hydrocarbonylation reaction of diethyl 2-ethylidene malonate with H2O[113]. The carboxylic acid could be deprotonated by Na2CO3 as the base, then undergoes a SET process with the excited

Scheme 18. Photocatalyzed hydro-alkylation/hydro-carbonylation of diethyl 2-ethylidene malonate with H2O.

Using a similar methodology, Zhang et al. realized hydro-carbonylation of activated alkenes under mild conditions[114]. The activating groups include pyridinyl, phenyl, and electron-withdrawing groups (EWG, such as carbonyl and sulfonyl groups), leading to high chemoselectivity to avoid interference by intramolecular inactivated vinyl or alkynyl group. The reaction is initiated by photocatalyzed SET process from Ph3P to *IrIII, forming radical cation Ph3P+, which could be attacked by carboxylate and furnish Int-19A. The Int-19A could transform into a reactive acyl radical by releasing POPh3, which undergoes radical addition to alkene and forms Int-19B. The following SET process between IrII and Int-19B completes the photoredox cycle and produces a carbanion intermediate, which could be protonated to yield the desired product [Scheme 19].

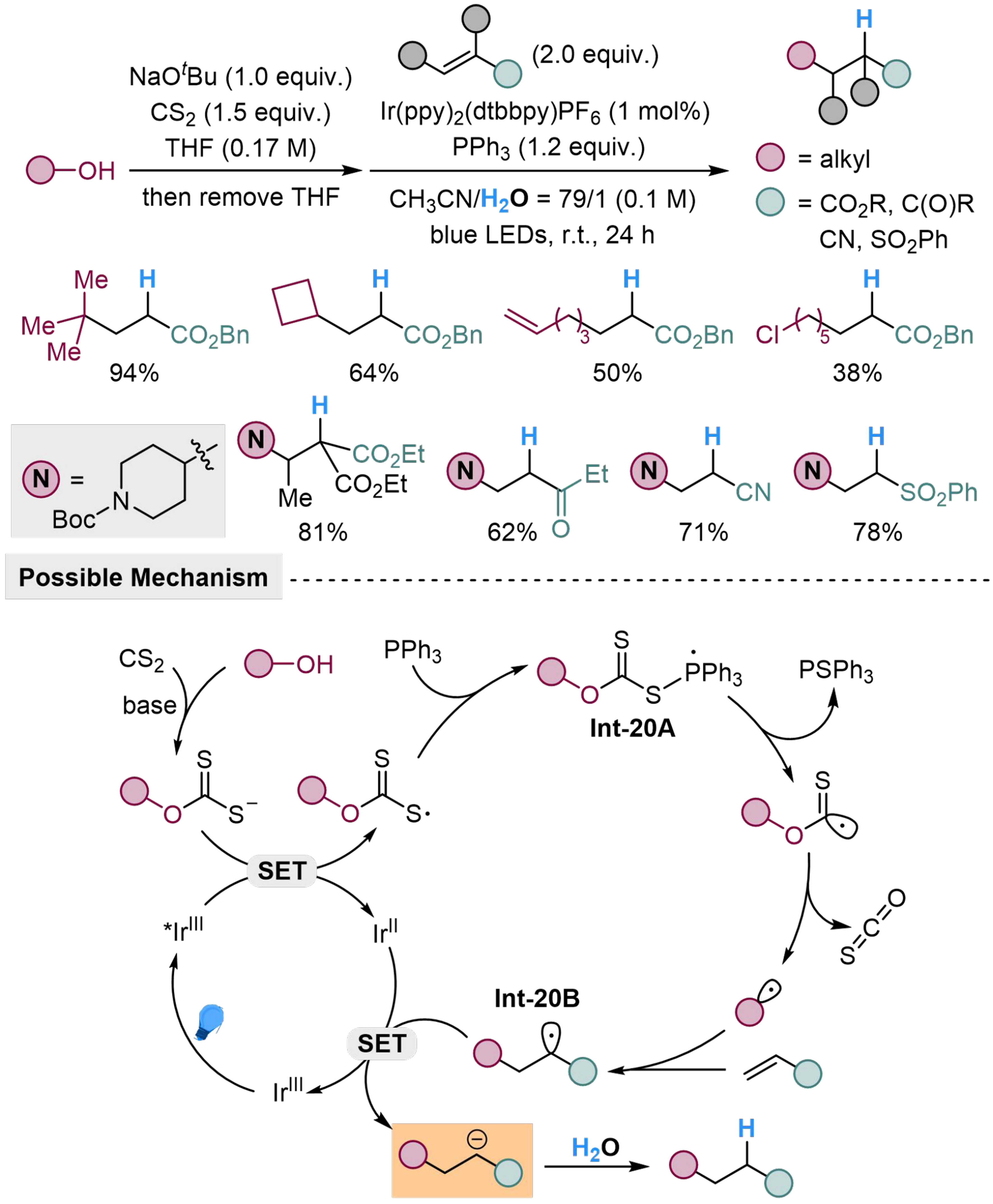

Alcohols are also potential carbon-centered radical precursors, which could perform a similar character as carboxylic acid in the above reactions. Guo et al. treat alcohol with carbon disulfide in the presence of sodium tert-butoxide to generate a xanthate anion, which would undergo SET with (4,4’-di-tert-butyl-2,2’-bipyridine)bis[(2-pyridinyl)phenyl]iridium(III) [Ir(ppy)2(dtbbpy)PF6] at excited states to generate alkoxythiocarbonyl radicals. The sulfur-centered radical would subsequently couple with PPh3 to form Int-20A, followed by continuous β-scission to produce the desired alkyl radical, extruding triphenylphosphine sulfide (PSPh3) and carbonyl sulfide (COS) as by-products. The in situ generated alkyl radical would undergo Giese-type addition to activated alkene to form Int-20B, followed by another SET process and protonation to yield the corresponding product [Scheme 20]. Tertiary, secondary, and primary aliphatic alcohols can all serve as the radical precursors, and tertiary alcohols feature better reactivity due to the stability of the corresponding alkyl radical. The activating groups on alkenes include carbonyl, cyano and sulfonyl groups, sharing similar reactivity for this reaction[115].

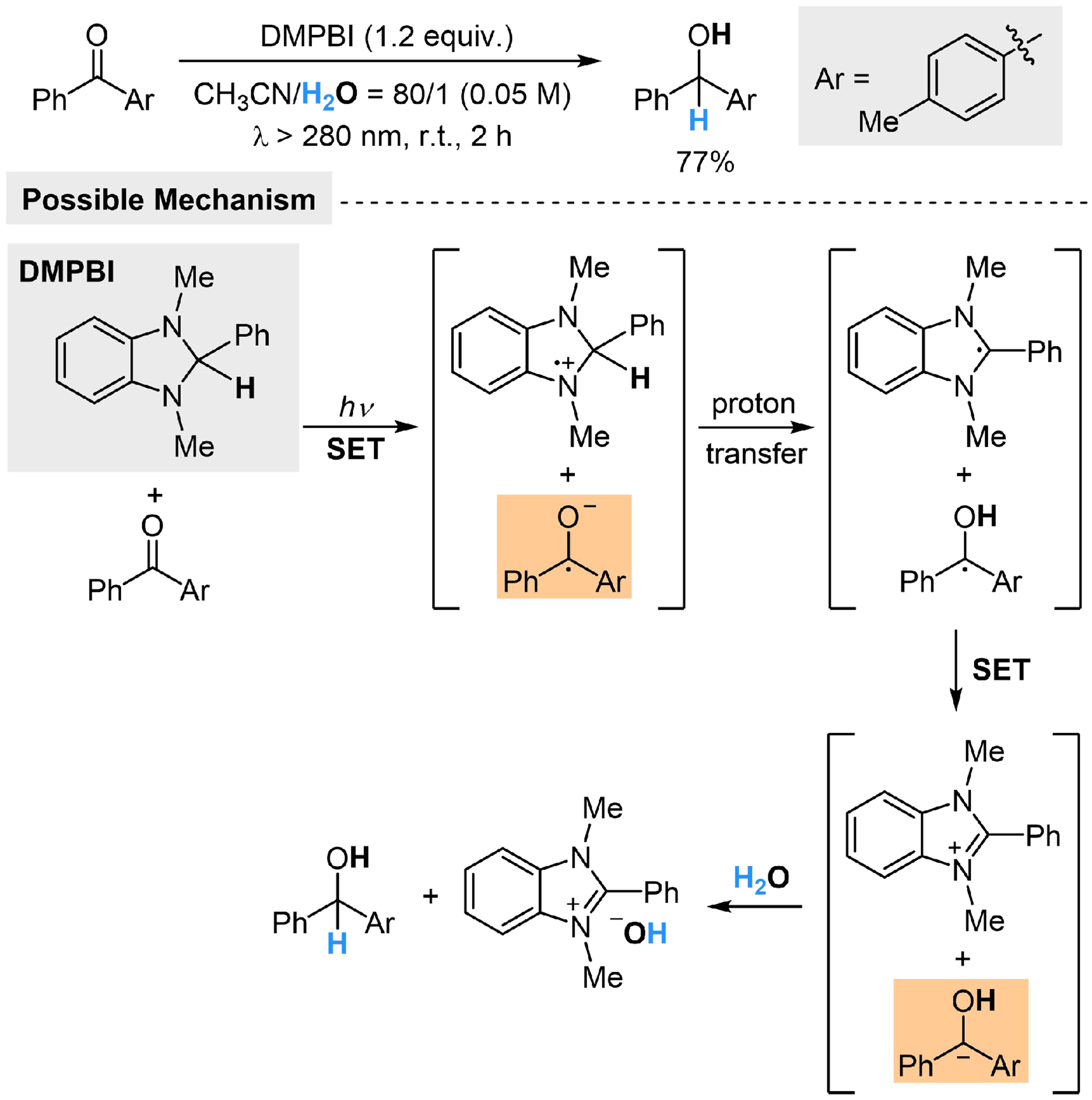

Hydrogenation of benzophenones with H2O could also be realized through substrate activation. Hasegawa et al. employ 1,3-dimethyl-2-phenylbenzimidazoline (DMPBI) as the photosensitizer and sacrificial reductant, and realize the hydrogenation of m-methylbenzophenone in moderate yield[116]. Under the irradiation of ultraviolet light, DMPBI could be excited and undergo SET with benzophenone, producing a radical ion pair [DMPBI·+ Sub·-]. Subsequent proton transfer and SET within [DMPBI·+ Sub·-] would produce a benzylic carbanion, which could be protonated by H2O to form the corresponding alcohol [Scheme 21]. When H2O is replaced with acetic acid, the product changes into 100% of benzpinacol, indicating that the acidity of H2O is the key point, which does not interfere the previous proton transfer step. However, this character makes H2O contribute only 50% as the proton source, while DMPBI provides the other 50%. In addition, the substrate scope and functional group tolerance of this reaction requires further exploration, to develop applicable methods for hydrogenation of benzophenone derivatives.

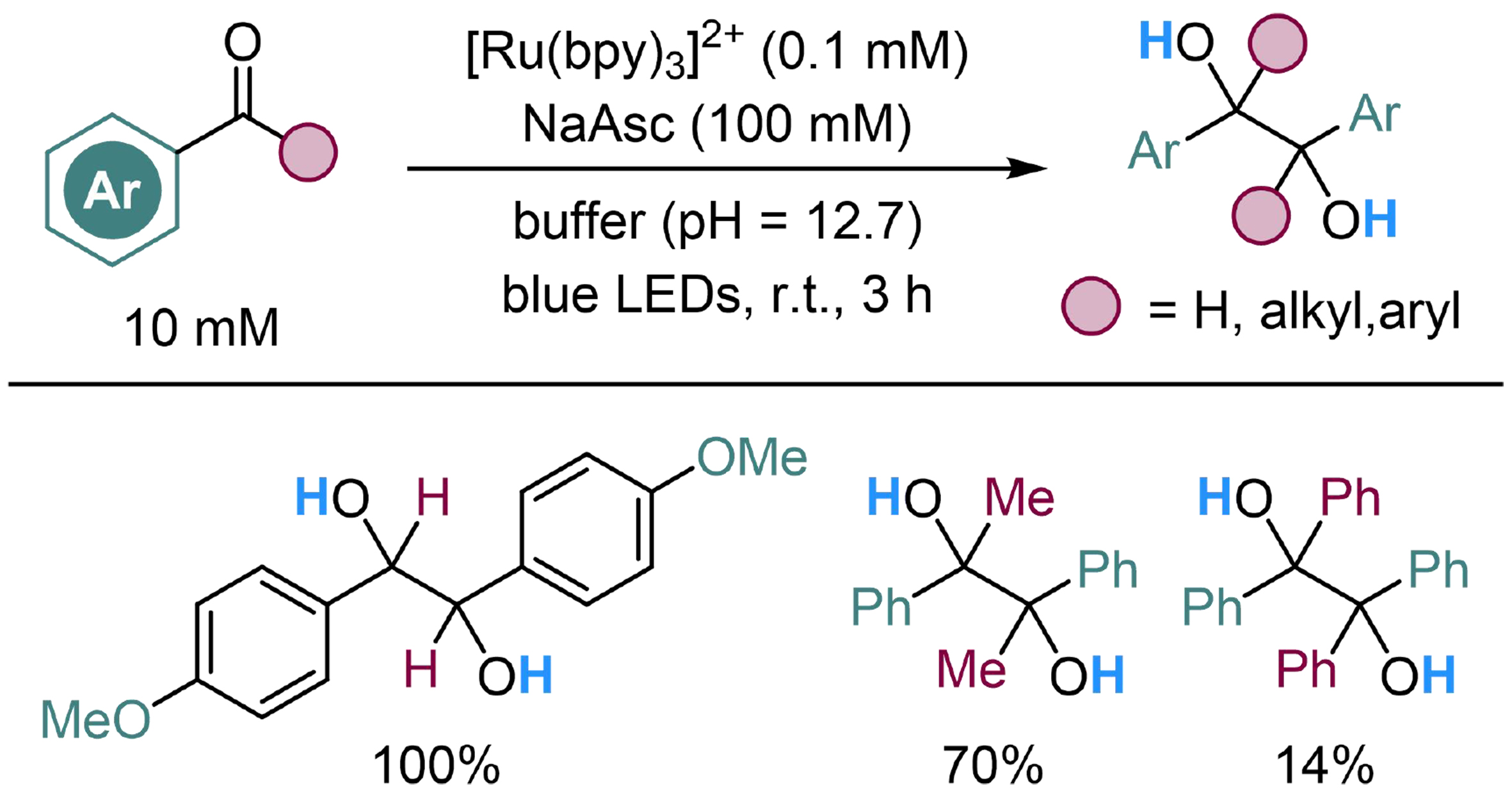

The above-mentioned strategy is also suitable for reductive coupling reaction of aromatic carbonyl compounds, which has been explored by Naumann and Goez, employing tris(2,2’-bipyridyl)dichlororuthenium(II) hexahydrate ([Ru(bpy)3]2+) as the photosensitizer and sodium ascorbate (NaAsc) as the sacrificial reductant in an aqueous buffer (pH = 12.7). Aromatic aldehydes and aryl-alkyl ketones show high reactivity in this reaction, while benzophenone shows a poor result due to the stability of the conjugated system in the substrate [Scheme 22][117].

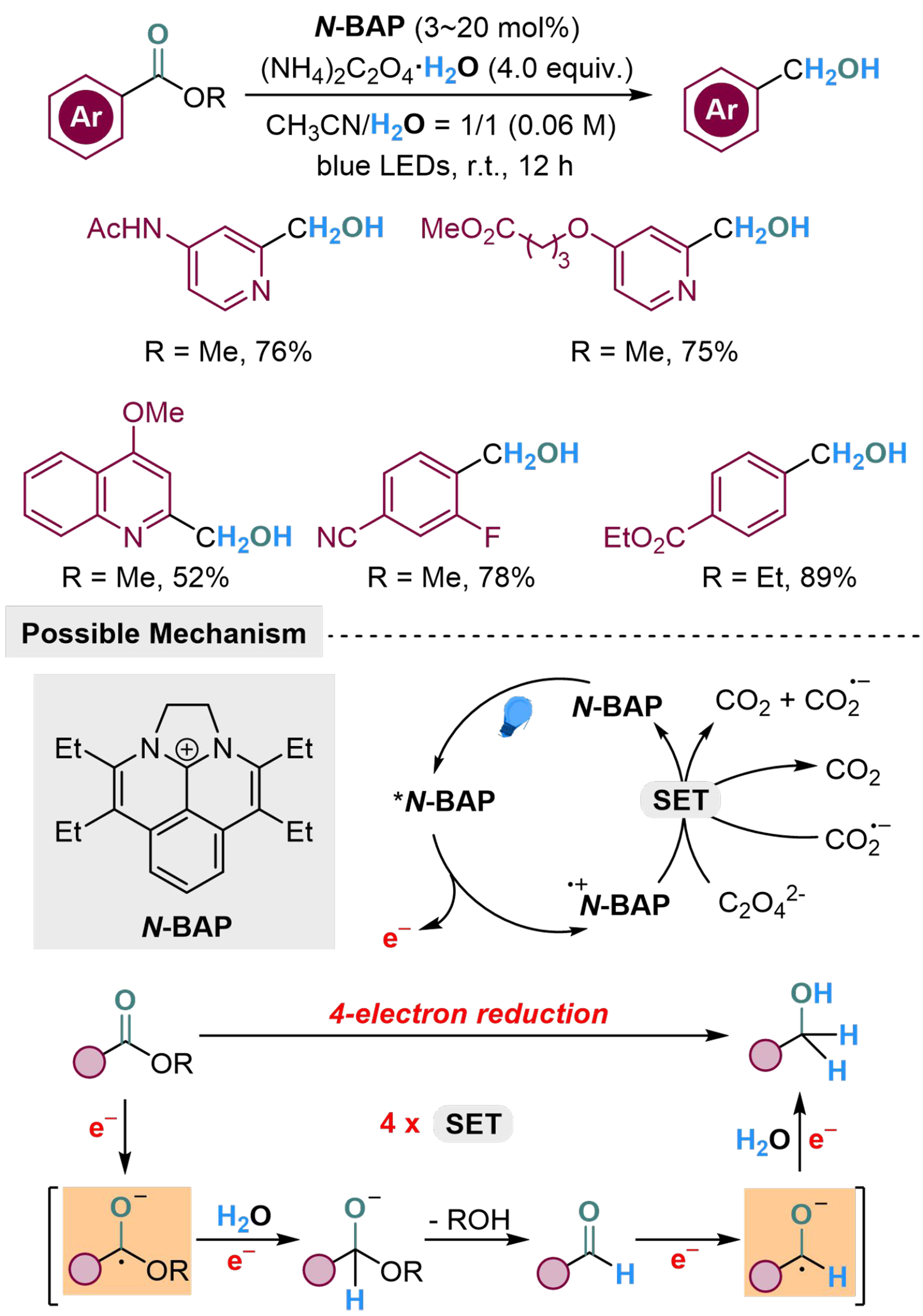

Photocatalytic reduction of esters to alcohols is also challenging, which requires an unprecedented successive quadruple SET process, via formation of carbinol anions. To overcome this difficulty, Okumura et al. have developed a diazabenzacenaphthenium photocatalyst N-BAP with proper ground redox potentials in both ground and excited states, and succeeded in transferring the electrons from oxalate to ester, to achieve the reduction of ester to alcohol[118]. The reaction undergoes a 4-electron reduction pathway, through a step-by-step activation of the substrate to generate oxygen anion and carbanion, which could abstract protons from H2O to obtain a hydrogenated result. The ester is limited within aryl ester, including phenyl ring, pyridine, and quinoline as the aromatic motif. The aliphatic ester group is unreactive in this reaction, while di-ester substrates would proceed this reaction to afford product with one ester group remained, showing great chemoselectivity [Scheme 23].

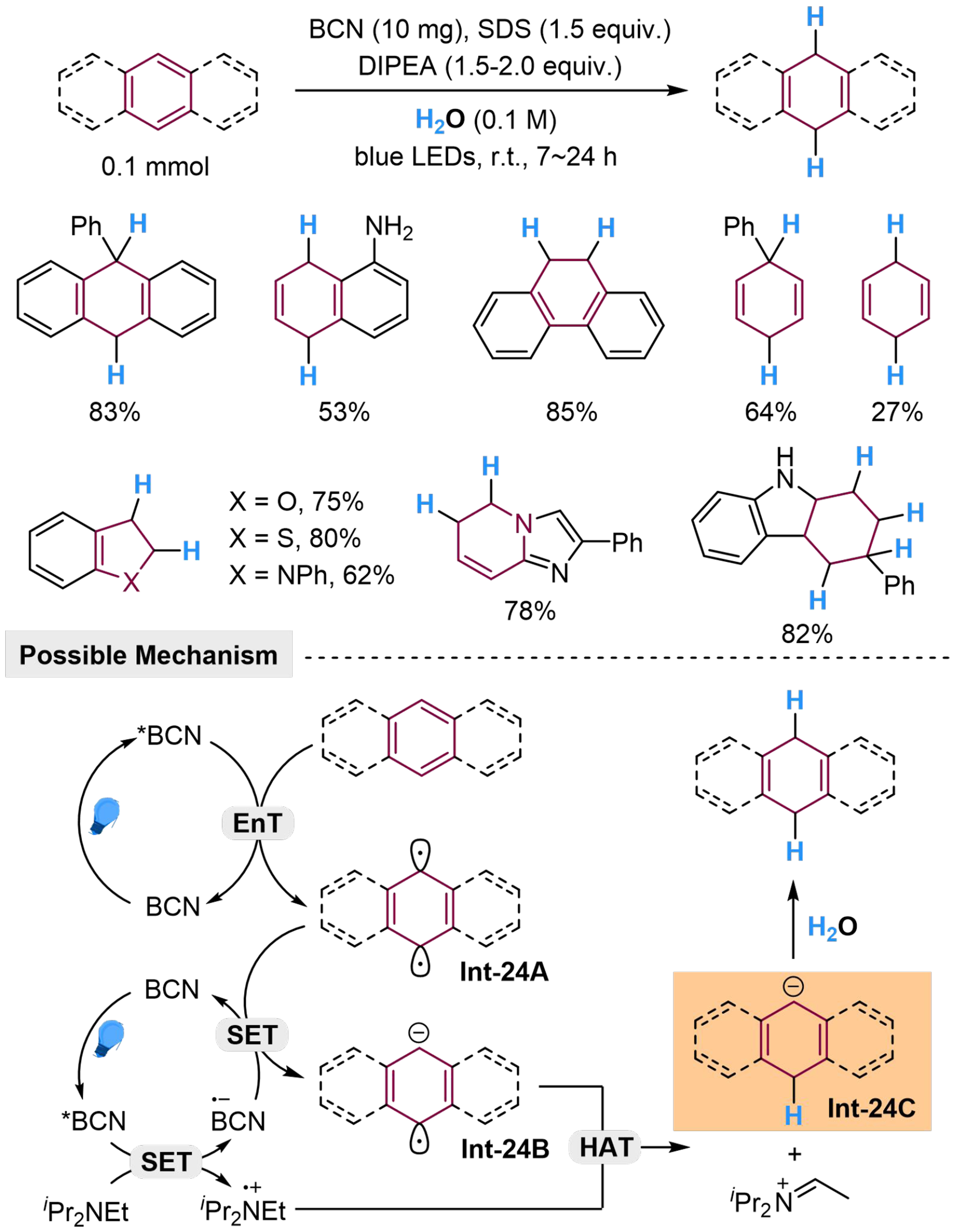

The utilization of H2O as a proton source in hydrogenation of arenes also provides potential methodology for a smooth introduction of deuterium (when using D2O) into complex ring systems, and has been realized by Yuan et al., using boron carbonitride (BCN) as photosensitizer and sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) as phase transfer catalyst[109]. Anthracene, phenanthrene, naphthalene, benzene and several heteroarenes could be hydrogenated with high regioselectivity. Using anthracene as an example, the possible mechanism of this reaction is discussed. Excited by the irradiation of blue light, *BCN at the excited state would sensitize anthracene by EnT to generate Int-24A at the triplet state. In parallel, the excited *BCN could undergo SET with iPr2NEt to form BCN·- and [iPr2NEt]·+, which would undergo SET and HAT process with Int-24A respectively and sequentially to form carbanion Int-24C, followed by protonation with H2O to produce the corresponding product [Scheme 24]. According to this mechanism, the hydrogen in DIPEA participates in the composition of the product, but a deuterium-labeled experiment with D2O presents a 99% deuterium incorporation. This might be explained by the fast proton exchange between iPr2NEt and D2O (or H2O).

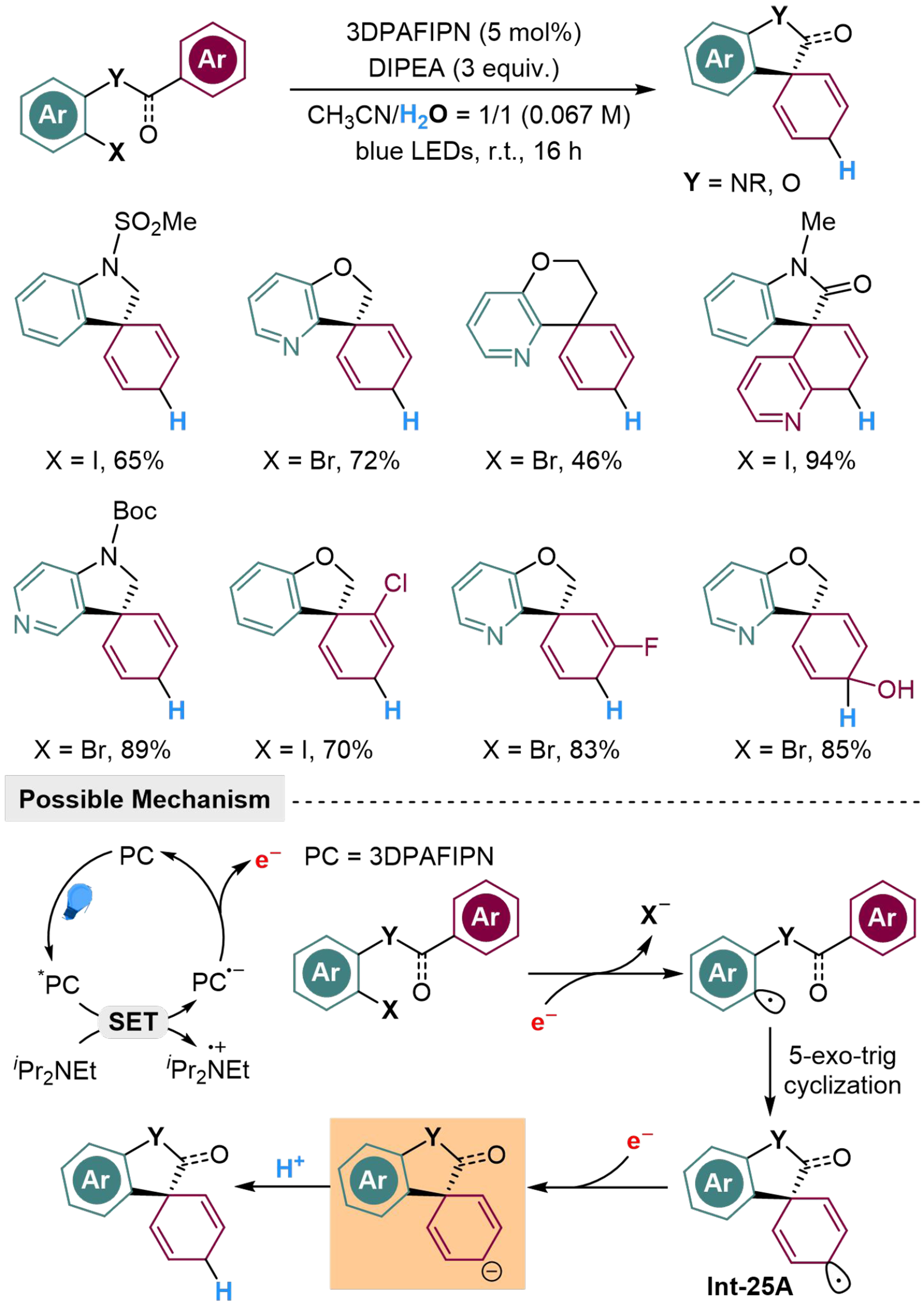

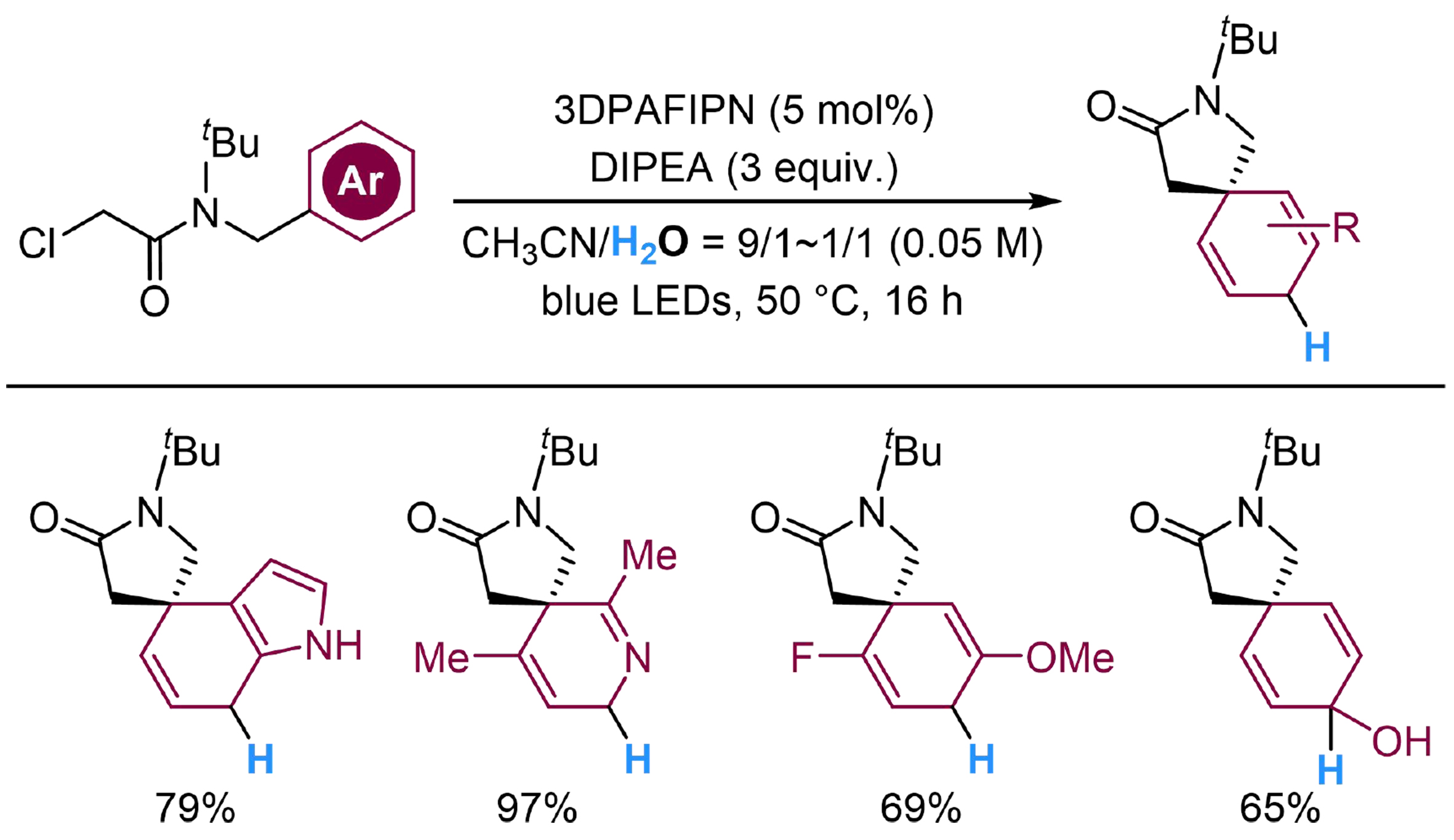

Dearomatization cyclization provides applicable approaches to complex spirocyclic cyclohexadienes, where utilization of H2O as a proton source might offer potential for further structural modifications. Flynn et al. have developed a photocatalyzed intramolecular dearomatized hydroarylation of (hetero)aryl halide-arene, to afford several spirocycles, where 2,4,6-tris(diphenylamino)-5-fluoroisophthalonitrile (3DPAFIPN) and DIPEA are employed to donate electrons smoothly[119]. Aza-aromatic rings, halogen atoms and hydroxyl group are all tolerant in the standard condition. Extracting an electron through SET from the photoredox cycle, the substrate would release a halide anion and transform into the corresponding aryl radical, where 5-exo-trig cyclization occurs to afford Int-25A. Subsequently, another electron would be delivered to Int-25A, followed by a protonation step to produce the spirocyclic product [Scheme 25]. Thereafter, they have broadened the radical precursor of this reaction from C(aryl)-X aryl halide bond to C(alkyl)-X aliphatic halide bond at the α-position of amide group, by raising the reaction temperature to 50 °C[120]. Substrates with indole unit, pyridine unit, halogen atoms and hydroxyl group on the aromatic ring all proceed smoothly in this reaction, through a similar mechanism as the above hydroarylation reaction [Scheme 26].

Reduction of alkynes/alkenes/ketones by activation to a proton acceptor (C-M species)

Combined with transition metal catalysis, the photocatalyzed reductive activation of substrates would draw to the formation of carbon-metal (C-M) species, which could be quenched by proton from H2O to be a proton acceptor.

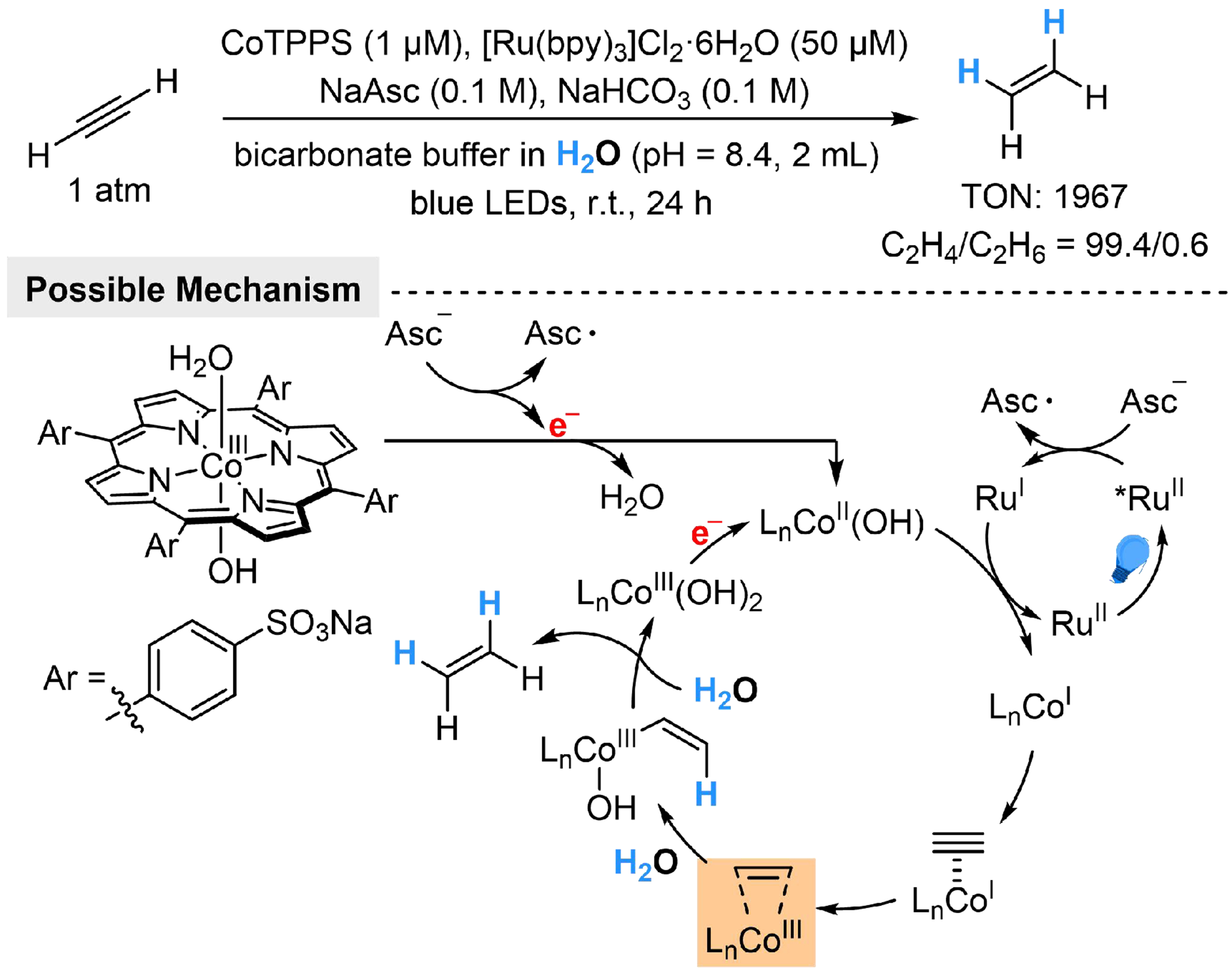

The introduction of water as a proton donor to the acetylene (C2H2) to ethylene (C2H4) reaction would provide sustainable edulcorating methods for industrial production of ethylene, which contains ~1 vol% acetylene contaminant[121,122]. Arcudi et al. have developed a ≥ 99% selective, photocatalyzed catalytical conversion of C2H2 to C2H4 using water as the proton source, featuring a high turnover number (TON) of 1967[123]. The reaction employs {meso-tetra(4-sulfonatophenyl)porphyrinato} cobalt(III) (CoTPPS) as the catalyst, tris(2,2’-bipyridyl)dichlororuthenium(II) hexahydrate ([Ru(bpy)3]2+) as the photosensitizer, and NaAsc sacrificial reductant in an aqueous bicarbonate buffer (pH = 8.4). The initial [LnCoIII(H2O)(OH)] species could be reduced by NaAsc to generate [LnCoII (OH)], followed by a SET process from RuI to form

The utilization of H2O through this strategy performs capability in hydro-functionalization reactions. Nakamura et al. have established a 4CzIPN/cobalt-catalyzed reductive cyclization of alkynals using H2O for cobalt catalyst turnover, successfully introduces the proton of H2O into products and improves the practicability of alkynal transformation[124]. This protocol is capable of the formation of five-, six-, and seven-membered rings, while both aryl and aliphatic aldehydes are susceptible to the transformation. The reaction is not interfered with by alkynyl group and carbonyl group away from the reaction site, showing great chemoselectivity and efficiency. The reaction starts from the reduction of excited *4CzIPN to radical anion by triethylamine (Et3N), which could reduce the original CoII species to CoI. The cobalt catalyst in a low valent state could generate oxacobaltcycle through oxidative cycloaddition to the alkyne and carbonyl group in the substrate, followed by subsequent reduction-protolysis step to produce the desired cyclic alcohols [Scheme 28]. When employing a simple alkyne without an aldehyde unit to the reaction, only a trace amount of alkene has been detected, indicating that the alternative pathway through the insertion of alkyne to the Co–H bond is negligible.

Scheme 28. 4CzIPN/Co-dual catalyzed reductive cyclization of alkynals with H2O. 4CzIPN: 2,4,5,6-tetra(9H-carbazol-9-yl) isophthalonitrile.

A similar method has been explored by Huo et al., using organotrifluoroborate as the radical precursor and H2O as the proton source, to realize enantioselective hydro-alkylation of the C=C double bond in α,β-unsaturated acyl imidazole[125]. The enantioselectivity is induced by the coordination effect between the chiral ruthenium catalyst and the acyl imidazole unit as the directing group. For alkene substituents at β-position, both aliphatic groups and aryl groups are applicable, while suitable substituents for trifluoroborates range from the benzylic group, alkoxymethyl group, secondary and tertiary aliphatic chains. The reaction is initiated by the generation of carbon-centered radical from the SET process between the organotrifluoroborate and excited *PC, followed by a Giese-type addition to Int-29A, which is formed by coordination from the substrate to the [Rh] catalyst. The generating Int-29B could capture an electron from PC·- to form enolate Int-29C, then protonated by H2O to furnish Int-29D, which could undergo ligand exchange with another molecule of substrate to produce the desired product and regenerate Int-29A [Scheme 29].

Reduction of alkynes/imines by activation of reductants to a water ionization accelerator

Considering the sacrificial reductants (such as organic amines) as the substrate, the amine cation generated from the photoredox cycle can accelerate the ionization of water through the hydrolysis reaction. The releasing proton could also be incorporated into the photoredox cycle to form reductive species for the hydrogenation of unsaturated compounds.

Zhong et al. developed an Eosin Y/Pd-dual catalyzed strategy to realize semi-reduction of alkynes with

Meanwhile, Zhang et al. employed DIPEA as the reductant and accelerated the proton-releasing process from H2O via N-centered cation, which successfully achieved the photocatalyzed transfer hydrogenation of N-sulfonylimines using H2O as the hydrogen source[127]. Diphenyl disulfide was introduced as the HAT reagent to facilitate the formation of N-centered cation through the photoredox cycle and converted into thiophenol. The proton released from H2O through hydrolysis of the amine cation was reduced to hydrogen atom by IrII, then added to the imine motif to generate a N-centered radical, which underwent HAT with thiophenol to produce the target product. Substrates with both electron-donating and electron-withdrawing substituents accomplished the reaction smoothly, while benzylic and alkyl substituents resulted in poor yields [Scheme 31].

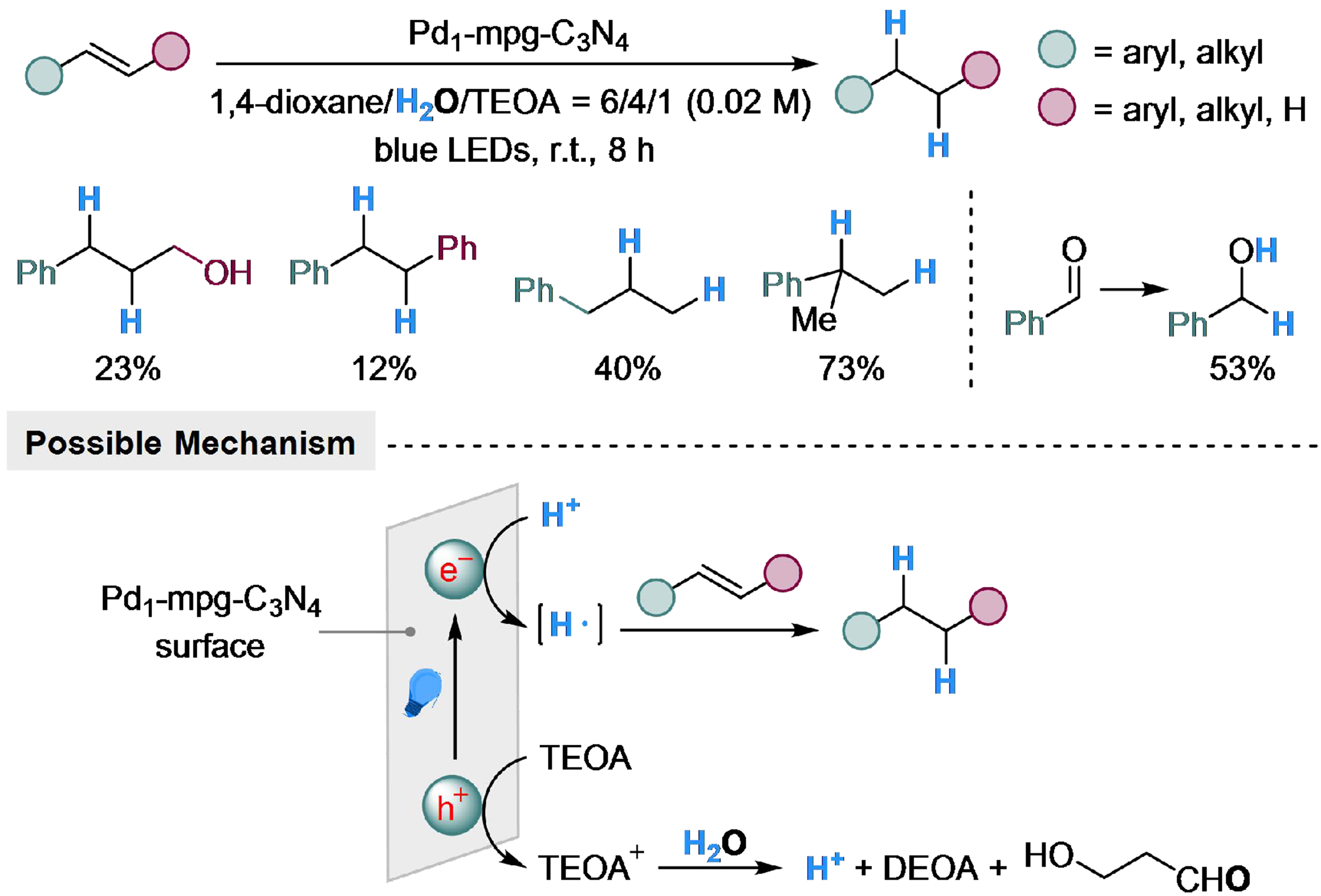

Single-atom catalysts have drawn considerable attention these years, for their high efficiency of metal utilization and great potential in hydrogenation reactions[128-131]. The carbon nitride material could combine with single-atom catalysts, to introduce photoactivity into these catalysts. Zhao et al. employed palladium single-atom catalysts supported on mesoporous carbon nitride (Pd1-mpg-C3N4) and realized photocatalyzed transfer hydrogenation with H2O[132]. The electron in the photocatalyst would transit to a high-energy state, leaving electrons on the surface. The TEOA could consume the electron hole and generate amino cation that undergoes hydrolysis with H2O, and the releasing proton would be reduced by the electron from photocatalyst to form hydrogen radical, which is capable of the hydrogenation of substrates. When 1 bar of H2 is introduced into the reaction with styrene as substrate, both the benzene ring and vinyl group could be hydrogenated, ruling out the possibility of indirect hydrogenation with the in situ generated H2. Styrene derivatives could achieve excellent yields in this reaction, while cinnamyl alcohol, allylbenzene, and trans-stilbene perform mediocrely. Benzaldehyde could be transformed into benzyl alcohol in moderate yield as well [Scheme 32].

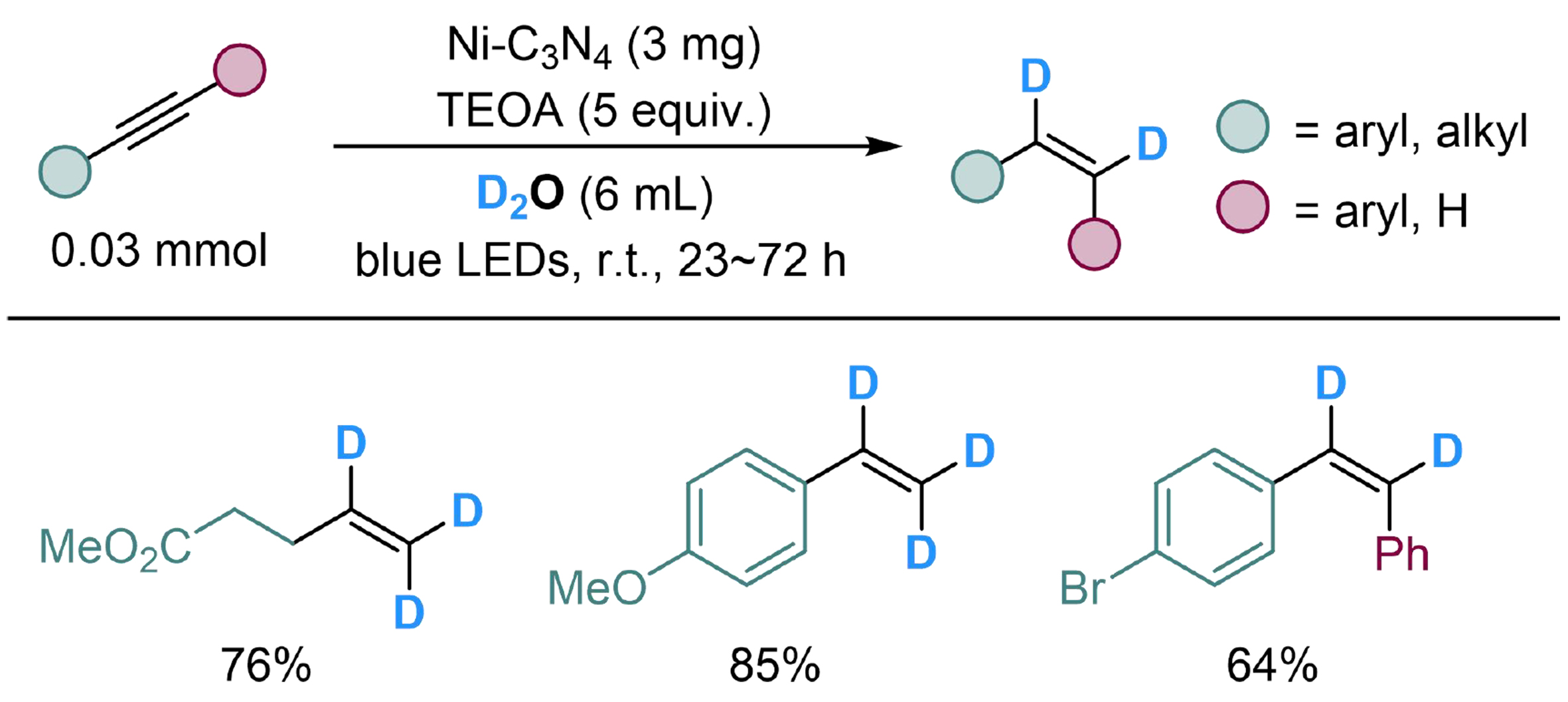

Meanwhile, Jia et al. employed nickel supported on carbon nitride (Ni-C3N4) and achieved semi-reduction of alkynes with H2O, using TEOA as the reductant through a similar process[133]. Both aliphatic and aryl alkynes could complete the conversion smoothly, among which, internal alkynes were converted into Z-alkenes with high chemoselectivity [Scheme 33]. Note that the hydrogen of terminal alkyne would undergo H/D exchange with D2O under this condition, to produce 1,1,2-trideuterated terminal alkenes.

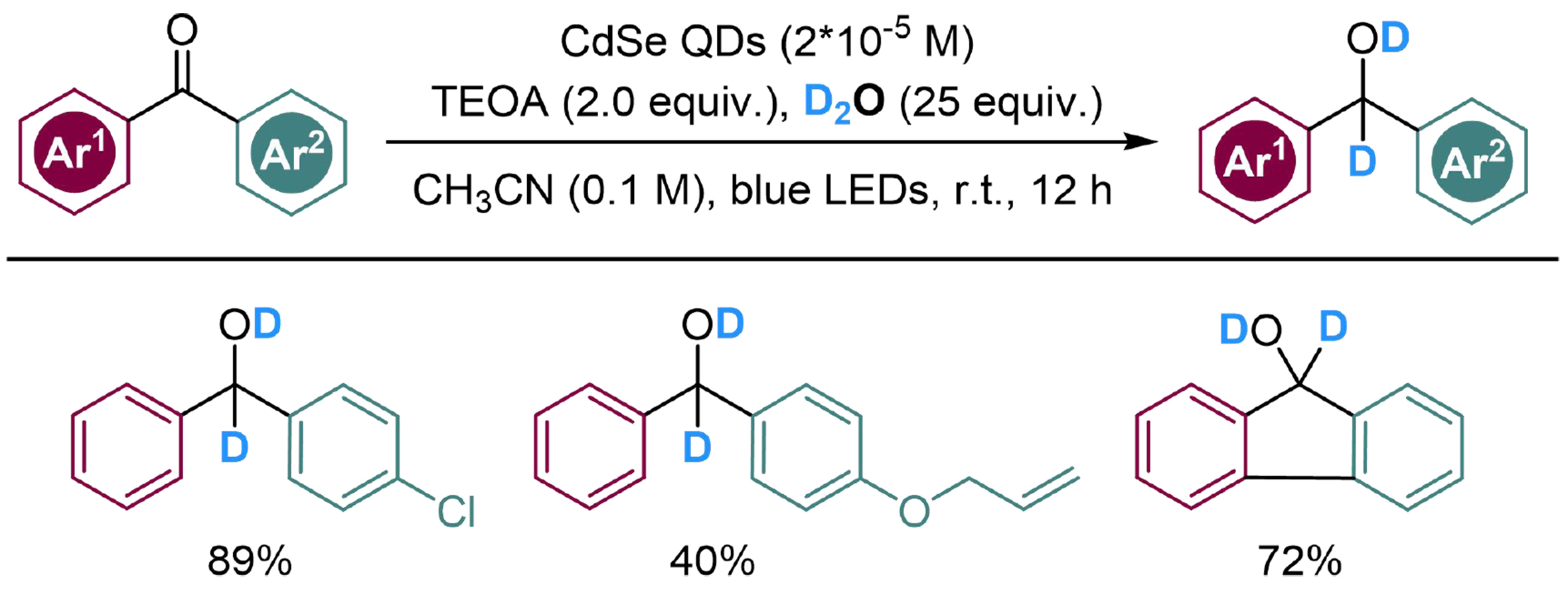

Photocatalyzed hydrogenation of benzophenones is a difficult issue; the carbonyl group in benzophenone is stabilized by the conjugated system, and the n-π* transition of the carbonyl group would disturb the excitation of additional photocatalyst. To handle this issue, a similar strategy as above has been applied in the reduction of benzophenone derivatives by Nan et al., where CdSe nanocrystal semiconductor with quantum dots (CdSe QDs) was introduced as the photocatalyst and active surface[134]. The reaction begins with the absorption of carbonyl substrates on the CdSe QD surfaces, followed by photocatalyzed reductive deuteration with the deuterium cations from the interaction between D2O and TEOA, to produce several α-deuterated benzhydrol derivatives [Scheme 34].

Application on the late-stage functionalization through indirect activation of water by substrate activation

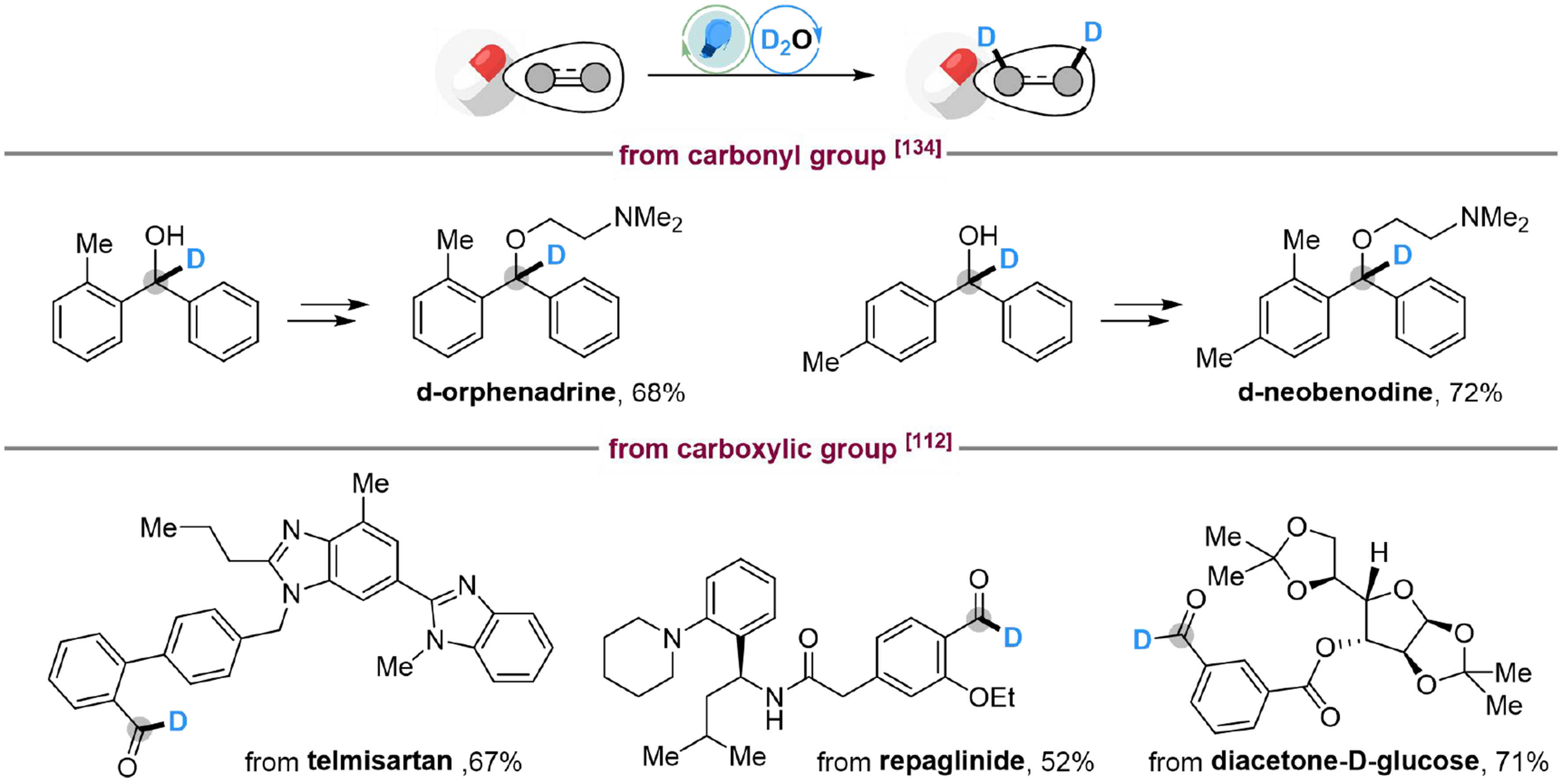

The indirect activation strategies have also been applied to the late-stage deuteration of unsaturated compounds using D2O as the deuterium source. For example, d-Orphenadrine and d-neobenodine with antihistaminic and anticholinergic properties are also available through two straightforward synthetic steps, including deuterium with D2O and the following alkylation[134]. Derivatives of telmisartan (antihypertensive drugs), repaglinide (insulin secretagogues) and diacetone-D-glucose with carboxylic groups could undergo deuteration with D2O to produce deuterated aldehydes, providing methods to modify complex carboxylic acids[112]. These examples indicate the potential for deuterium labeling of drugs and bioactive molecules by indirect photocatalyzed activation of water [Scheme 35].

CONCLUSION AND OUTLOOK

Photocatalyzed H2O-incorporated reductive addition reaction of unsaturated bonds has been developed as a powerful transfer hydrogenation strategy these days, showing great potential in the utilization of H2O and introduction of deuterium into complex skeletons by D2O. These methods have been summarized by categorizing the reaction mechanism into coordination activation, oxidative addition activation, and substrate activation. Moreover, based on the typical mechanism on water activation, utilization of deuterium water for the synthesis of multi-deuterated organic products shows great potential.

Despite these advances, many unsolved difficulties and challenges remain. (a) Most methods for photocatalyzed coordination activation of H2O generate an active hydrogen radical from water splitting. However, the hydrogen radical is too active, bringing competition between substrate hydrogenation and hydrogen evolution, while leading to limitations on the functional group tolerance. The regulation of the water-activating agents (including semiconductors or other positive center precursors) needs further explorations, in order to control the dissociation of O-H bond and avoid direct generation of hydrogen radicals; (b) Since the radical mechanism is one of the dominant processes in photocatalyzed transfer hydrogenation with H2O, it is challenging to control the regioselectivity and enantioselectivity. Developing methods to combine radical activation of H2O and asymmetrical synthesis would be a promising direction; (c) Sacrificial reductants are generally necessary due to the low reductive potential of H2O itself, which produce worthless by-products at the oxidation site, resulting in insufficient atomic economy. On the other side, replacing the sacrificial reductant with organics that could produce value-added oxidative products simultaneously is also favorable; (d) Noble-metal catalysts still play a dominant role in the photocatalyzed H2O-incorporated hydrogenation reactions. Due to the scarcity and high expense of noble metals, it is important to develop non-noble-metal or non-metal catalysts for these reactions; (e) The applications on the utilization of water as a hydrogen source for the synthesis or late-stage functionalization of drugs, bioactive molecules or agrochemicals are achievable and valuable. However, the current studies remain limited and require further exploration. Despite the remaining challenges in this field, we believe photocatalyzed water chemistry in organic synthesis would not only develop methods for utilizing the hydrogen in water for sustainable synthesis, but also provide a deeper understanding of the properties of

DECLARATIONS

Acknowledgments

We sincerely thank all leading chemists and co-workers in the development of photocatalyzed reduction of unsaturated compounds with water. We also thank Yaping Yi, Zeyu Zhang, and Jiayuan Li from Tsinghua University for their advice. All authors declare that all images are original and created by the authors.

Authors’ contributions

Wrote the paper: Chen, S.

Guided this work, gave valuable suggestions and discussion for the review and revised the paper: Lu, W.; Xi, C.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Financial support and sponsorship

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 22371159 and 22071134).

Conflicts of interest

All authors declared that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026.

REFERENCES

1. Johnson, N. B.; Lennon, I. C.; Moran, P. H.; Ramsden, J. A. Industrial-scale synthesis and applications of asymmetric hydrogenation catalysts. Acc. Chem. Res. 2007, 40, 1291-9.

2. Crespo-Quesada, M.; Cárdenas-Lizana, F.; Dessimoz, A.; Kiwi-Minsker, L. Modern trends in catalyst and process design for alkyne hydrogenations. ACS. Catal. 2012, 2, 1773-86.

3. Fürstner, A. trans-Hydrogenation, gem-hydrogenation, and trans-hydrometalation of alkynes: an interim report on an unorthodox reactivity paradigm. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 11-24.

4. Decker, D.; Drexler, H.; Heller, D.; Beweries, T. Homogeneous catalytic transfer semihydrogenation of alkynes - an overview of hydrogen sources, catalysts and reaction mechanisms. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2020, 10, 6449-63.

5. Klingler, F. D. Asymmetric hydrogenation of prochiral amino ketones to amino alcohols for pharmaceutical use. Acc. Chem. Res. 2007, 40, 1367-76.

6. Patel, R. N. Biocatalytic synthesis of chiral alcohols and amino acids for development of pharmaceuticals. Biomolecules 2013, 3, 741-77.

7. Koesoema, A. A.; Standley, D. M.; Senda, T.; Matsuda, T. Impact and relevance of alcohol dehydrogenase enantioselectivities on biotechnological applications. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2020, 104, 2897-909.

8. Lindlar, H.; Dubuis, R. Palladium catalyst for partical reduction of acetylenes. Org. Synth. 1966, 46, 89.

9. Ohkuma, T.; Ooka, H.; Ikariya, T.; Noyori, R. Preferential hydrogenation of aldehydes and ketones. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995, 117, 10417-8.

10. Noyori, R.; Ohkuma, T. Asymmetric catalysis by architectural and functional molecular engineering: practical chemo- and stereoselective hydrogenation of ketones. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2001, 40, 40-73.

11. Morris, R. H. Asymmetric hydrogenation, transfer hydrogenation and hydrosilylation of ketones catalyzed by iron complexes. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2009, 38, 2282-91.

12. Langer, R.; Leitus, G.; Ben-David, Y.; Milstein, D. Efficient hydrogenation of ketones catalyzed by an iron pincer complex. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2011, 50, 2120-4.

13. Li, Y. Y.; Yu, S. L.; Shen, W. Y.; Gao, J. X. Iron-, cobalt-, and nickel-catalyzed asymmetric transfer hydrogenation and asymmetric hydrogenation of ketones. Acc. Chem. Res. 2015, 48, 2587-98.

14. Lan, X.; Wang, T. Highly selective catalysts for the hydrogenation of unsaturated aldehydes: a review. ACS. Catal. 2020, 10, 2764-90.

15. Luneau, M.; Lim, J. S.; Patel, D. A.; Sykes, E. C. H.; Friend, C. M.; Sautet, P. Guidelines to achieving high selectivity for the hydrogenation of α,β-unsaturated aldehydes with bimetallic and dilute alloy catalysts: a review. Chem. Rev. 2020, 120, 12834-72.

16. Zhang, F.; Zhang, F.; Li, M.; Xie, J.; Zhou, Q. Enantioselective hydrogenation of dialkyl ketones. Nat. Catal. 2020, 3, 621-7.

17. Wu, X.; Li, X.; Zanotti-Gerosa, A.; et al. RhIII- and IrIII-catalyzed asymmetric transfer hydrogenation of ketones in water. Chemistry 2008, 14, 2209-22.

18. He, Y.; Fan, Q. Advances in transfer hydrogenation of carbonyl compounds in water. ChemCatChem 2015, 7, 398-400.

19. Foubelo, F.; Nájera, C.; Yus, M. Catalytic asymmetric transfer hydrogenation of ketones: recent advances. Tetrahedron. Asymmetr. 2015, 26, 769-90.

20. Štefane, B.; Požgan, F. Metal-catalysed transfer hydrogenation of ketones. Top. Curr. Chem. 2016, 374, 18.

21. Farrar-Tobar, R. A.; Dell’acqua, A.; Tin, S.; de Vries, J. G. Metal-catalysed selective transfer hydrogenation of α,β-unsaturated carbonyl compounds to allylic alcohols. Green. Chem. 2020, 22, 3323-57.

22. Nie, R.; Tao, Y.; Nie, Y.; et al. Recent advances in catalytic transfer hydrogenation with formic acid over heterogeneous transition metal catalysts. ACS. Catal. 2021, 11, 1071-95.

23. Wagh, Y. S.; Asao, N. Selective transfer semihydrogenation of alkynes with nanoporous gold catalysts. J. Org. Chem. 2015, 80, 847-51.

24. Kusy, R.; Lindner, M.; Wagner, J.; Grela, K. Ligand-to-metal ratio controls stereoselectivity: highly functional-group-tolerant, iridium-based, (E)-selective alkyne transfer semihydrogenation. Chem. Catal. 2022, 2, 1346-61.

25. Ghosh, T.; Slanina, T.; König, B. Visible light photocatalytic reduction of aldehydes by Rh(III)-H: a detailed mechanistic study. Chem. Sci. 2015, 6, 2027-34.

26. Tian, W. F.; He, Y. Q.; Song, X. R.; et al. cis-Selective transfer semihydrogenation of alkynes by merging visible-light catalysis with cobalt catalysis. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2020, 362, 1032-8.

27. Cho, B. T. Recent development and improvement for boron hydride-based catalytic asymmetric reduction of unsymmetrical ketones. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2009, 38, 443-52.

28. Query, I. P.; Squier, P. A.; Larson, E. M.; Isley, N. A.; Clark, T. B. Alkoxide-catalyzed reduction of ketones with pinacolborane. J. Org. Chem. 2011, 76, 6452-6.

29. Magano, J.; Dunetz, J. R. Large-scale carbonyl reductions in the pharmaceutical industry. Org. Process. Res. Dev. 2012, 16, 1156-84.

30. Chakraborty, S.; Bhattacharya, P.; Dai, H.; Guan, H. Nickel and iron pincer complexes as catalysts for the reduction of carbonyl compounds. Acc. Chem. Res. 2015, 48, 1995-2003.

31. Xi, Z. W.; Yang, L.; Wang, D. Y.; et al. Visible light induced reduction and pinacol coupling of aldehydes and ketones catalyzed by core/shell quantum dots. J. Org. Chem. 2021, 86, 2474-88.

32. Spiegel, D. A.; Wiberg, K. B.; Schacherer, L. N.; Medeiros, M. R.; Wood, J. L. Deoxygenation of alcohols employing water as the hydrogen atom source. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 12513-5.

33. Kolmar, S. S.; Mayer, J. M. SmI2(H2O)n reduction of electron rich enamines by proton-coupled electron transfer. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 10687-92.

34. Soulard, V.; Villa, G.; Vollmar, D. P.; Renaud, P. Radical deuteration with D2O: catalysis and mechanistic insights. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 155-8.

35. Yang, X.; Reijerse, E. J.; Bhattacharyya, K.; et al. Radical activation of N-H and O-H bonds at bismuth(II). J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 16535-44.

36. Zhang, X.; Xie, X.; Liu, Y. Nickel-catalyzed highly regioselective hydrocyanation of terminal alkynes with Zn(CN)2 using water as the hydrogen source. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 7385-9.

37. Paradas, M.; Campaña, A. G.; Jiménez, T.; et al. Understanding the exceptional hydrogen-atom donor characteristics of water in TiIII-mediated free-radical chemistry. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 12748-56.

38. Kondo, M.; Tatewaki, H.; Masaoka, S. Design of molecular water oxidation catalysts with earth-abundant metal ions. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2021, 50, 6790-831.

39. Boekell, N. G.; Flowers, R. A. Coordination-induced bond weakening. Chem. Rev. 2022, 122, 13447-77.

40. Zhang, J.; Mück-Lichtenfeld, C.; Studer, A. Photocatalytic phosphine-mediated water activation for radical hydrogenation. Nature 2023, 619, 506-13.

41. Barber, E. R.; Hynds, H. M.; Stephens, C. P.; Lemons, H. E.; Fredrickson, E. T.; Wilger, D. J. Nickel-catalyzed hydroarylation of alkynes under reductive conditions with aryl bromides and water. J. Org. Chem. 2019, 84, 11612-22.

42. Wang, Y.; Cao, X.; Zhao, L.; et al. Generalized chemoselective transfer hydrogenation/hydrodeuteration. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2020, 362, 4119-29.

43. Li, K.; Yang, C.; Chen, J.; et al. Anion controlled stereodivergent semi-hydrogenation of alkynes using water as hydrogen source. Asian. J. Org. Chem. 2021, 10, 2143-6.

44. Li, X.; Li, Y.; Wang, Z.; et al. Nickel-catalyzed stereoselective cascade C–F functionalizations of gem-difluoroalkenes. ACS. Catal. 2023, 13, 2135-41.

45. Wu, Y.; Ao, Y.; Li, Z.; et al. Modulation of metal species as control point for Ni-catalyzed stereodivergent semihydrogenation of alkynes with water. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 1655.

46. Paradas, M.; Campaña, A. G.; Marcos, M. L.; et al. Unprecedented H-atom transfer from water to ketyl radicals mediated by Cp2TiCl. Dalton. Trans. 2010, 39, 8796-800.

47. Szostak, M.; Spain, M.; Procter, D. J. Ketyl-type radicals from cyclic and acyclic esters are stabilized by SmI2(H2O)n: the role of SmI2(H2O)n in post-electron transfer steps. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 8459-66.

48. Chciuk, T. V.; Flowers, R. A. Proton-coupled electron transfer in the reduction of arenes by SmI2-water complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 11526-31.

49. Xuan, Q.; Zhao, C.; Song, Q. Umpolung of protons from H2O: a metal-free chemoselective reduction of carbonyl compounds via B2pin2/H2O systems. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2017, 15, 5140-4.

50. Cummings, S. P.; Le, T. N.; Fernandez, G. E.; Quiambao, L. G.; Stokes, B. J. Tetrahydroxydiboron-mediated palladium-catalyzed transfer hydrogenation and deuteriation of alkenes and alkynes using water as the stoichiometric H or D atom donor. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 6107-10.

51. Ojha, D. P.; Gadde, K.; Prabhu, K. R. Generation of hydrogen from water: a Pd-catalyzed reduction of water using diboron reagent at ambient conditions. Org. Lett. 2016, 18, 5062-5.

52. Han, X.; Hu, J.; Chen, C.; Yuan, Y.; Shi, Z. Copper-catalysed, diboron-mediated cis-dideuterated semihydrogenation of alkynes with heavy water. Chem. Commun. 2019, 55, 6922-5.

53. Zhao, C. Q.; Chen, Y. G.; Qiu, H.; Wei, L.; Fang, P.; Mei, T. S. Water as a hydrogenating agent: stereodivergent Pd-catalyzed semihydrogenation of alkynes. Org. Lett. 2019, 21, 1412-6.

54. Chen, K.; Zhu, H.; Li, Y.; Peng, Q.; Guo, Y.; Wang, X. Dinuclear cobalt complex-catalyzed stereodivergent semireduction of alkynes: switchable selectivities controlled by H2O. ACS. Catal. 2021, 11, 13696-705.

55. Li, G.; Jiang, H.; Li, J. Use of water as a direct hydrogen donor in supercritical carbon dioxide: a novel and efficient Zn-H2O-CO2 system for selective reduction of aldehydes to alcohols. Green. Chem. 2001, 3, 250-1.

56. Flinker, M.; Yin, H.; Juhl, R. W.; et al. Efficient water reduction with sp3-sp3 Diboron(4) compounds: application to hydrogenations, H-D exchange reactions, and carbonyl reductions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2017, 56, 15910-5.

57. Mokhtar, M. M.; Andersen, J. M.; Kister, E. A.; et al. A mechanistic perspective on the mechanochemical method to reduce carbonyl groups with stainless steel and water. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2023, 26, e202300149.

58. Zhu, N.; Su, M.; Wan, W. M.; Li, Y.; Bao, H. Practical method for reductive deuteration of ketones with magnesium and D2O. Org. Lett. 2020, 22, 991-6.

59. Bach, T.; Hehn, J. P. Photochemical reactions as key steps in natural product synthesis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2011, 50, 1000-45.

60. Lang, X.; Chen, X.; Zhao, J. Heterogeneous visible light photocatalysis for selective organic transformations. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2014, 43, 473-86.

61. Buzzetti, L.; Crisenza, G. E. M.; Melchiorre, P. Mechanistic studies in photocatalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2019, 58, 3730-47.

62. Zhao, E.; Zhang, W.; Dong, L.; Zbořil, R.; Chen, Z. Photocatalytic transfer hydrogenation reactions using water as the proton source. ACS. Catal. 2023, 13, 7557-67.

63. Russo, C.; Brunelli, F.; Tron, G. C.; Giustiniano, M. Visible-light photoredox catalysis in water. J. Org. Chem. 2023, 88, 6284-93.

64. Warren, J. J.; Tronic, T. A.; Mayer, J. M. Thermochemistry of proton-coupled electron transfer reagents and its implications. Chem. Rev. 2010, 110, 6961-7001.

65. Agarwal, R. G.; Coste, S. C.; Groff, B. D.; et al. Free energies of proton-coupled electron transfer reagents and their applications. Chem. Rev. 2022, 122, 1-49.

66. Chciuk, T. V.; Anderson, W. R. J.; Flowers, R. A. Proton-coupled electron transfer in the reduction of carbonyls by samarium diiodide-water complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 8738-41.

67. Chciuk, T. V.; Anderson, W. R. J.; Flowers, R. A. Interplay between substrate and proton donor coordination in reductions of carbonyls by SmI2-water through proton-coupled electron-transfer. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 15342-52.

68. Bartulovich, C. O.; Flowers, R. A. Coordination-induced O-H bond weakening in Sm(II)-water complexes. Dalton. Trans. 2019, 48, 16142-7.

69. Boyd, E. A.; Peters, J. C. Sm(II)-mediated proton-coupled electron transfer: quantifying very weak N-H and O-H homolytic bond strengths and factors controlling them. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 21337-46.

70. Cuerva, J. M.; Campaña, A. G.; Justicia, J.; et al. Water: the ideal hydrogen-atom source in free-radical chemistry mediated by Ti(III) and other single-electron-transfer metals? Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2006, 45, 5522-6.

71. Gansäuer, A.; Behlendorf, M.; Cangönül, A.; et al. H2O activation for hydrogen-atom transfer: correct structures and revised mechanisms. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2012, 51, 3266-70.

72. Tantawy, W.; Zipse, H. Hydroxylic solvents as hydrogen atom donors in radical reactions. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2007, 2007, 5817-20.

73. Pandey, G.; Pooranchand, D.; Bhalerao, U. Photoinduced single electron transfer activation of organophosphines: nucleophilic trapping of phosphine radical cation. Tetrahedron 1991, 47, 1745-52.

74. Chen, S.; Xi, C. Photoinduced catalytical reduction of carbonyl compounds using water as a hydrogen source. Org. Chem. Front. 2024, 11, 5415-21.

75. Xie, Z.; Zheng, Y.; Liao, Z.; et al. Photoredox-catalyzed hydrogenation of alkenes assisted by an in situ generated PPh3(OH) radical and acetic acid. Org. Chem. Front. 2024, 11, 4187-93.

76. Kang, W. J.; Pan, Y.; Ding, A.; Guo, H. Organophotocatalytic alkene reduction using water as a hydrogen donor. Org. Lett. 2023, 25, 7633-8.

77. Kang, W.; Li, B.; Zhao, Z.; et al. Generation of thioxanthone hydrogen anion by double photoreduction and uses for catalytic photoreductions. ACS. Catal. 2023, 13, 13588-96.

78. Wertjes, W. C.; Southgate, E. H.; Sarlah, D. Recent advances in chemical dearomatization of nonactivated arenes. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2018, 47, 7996-8017.

79. Hook, J. M.; Mander, L. N. Recent developments in the Birch reduction of aromatic compounds: applications to the synthesis of natural products. Nat. Prod. Rep. 1986, 3, 35.

81. Zimmerman, H. E. A mechanistic analysis of the Birch Reduction. Acc. Chem. Res. 2012, 45, 164-70.

82. Burrows, J.; Kamo, S.; Koide, K. Scalable Birch reduction with lithium and ethylenediamine in tetrahydrofuran. Science 2021, 374, 741-6.

83. Benkeser, R. A.; Robinson, R. E.; Sauve, D. M.; Thomas, O. H. Reduction of organic compounds by lithium in low molecular weight amines. I. selective reduction of aromatic hydrocarbons to monoölefins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1955, 77, 3230-3.

84. Nandi, P.; Dye, J. L.; Jackson, J. E. Birch reductions at room temperature with alkali metals in silica gel (Na2K-SG(I)). J. Org. Chem. 2009, 74, 5790-2.

85. Costanzo, M. J.; Patel, M. N.; Petersen, K. A.; Vogt, P. F. Ammonia-free Birch reductions with sodium stabilized in silica gel, Na–SG(I). Tetrahedron. Lett. 2009, 50, 5463-6.

86. Szostak, M.; Spain, M.; Procter, D. J. Determination of the effective redox potentials of SmI2, SmBr2, SmCl2, and their complexes with water by reduction of aromatic hydrocarbons. Reduction of anthracene and stilbene by samarium(II) iodide-water complex. J. Org. Chem. 2014, 79, 2522-37.

87. Donohoe, T. J.; Thomas, R. E. The partial reduction of electron-deficient pyrroles: procedures describing both Birch (Li/NH3) and ammonia-free (Li/DBB) conditions. Nat. Protoc. 2007, 2, 1888-95.

88. Lei, P.; Ding, Y.; Zhang, X.; et al. A practical and chemoselective ammonia-free Birch reduction. Org. Lett. 2018, 20, 3439-42.

89. Yoo, B. I.; Kim, Y. J.; You, Y.; Yang, J. W.; Kim, S. W. Birch reduction of aromatic compounds by inorganic electride [Ca2N]+·e- in an alcoholic solvent: an analogue of solvated electrons. J. Org. Chem. 2018, 83, 13847-53.

90. Urban, S.; Beiring, B.; Ortega, N.; Paul, D.; Glorius, F. Asymmetric hydrogenation of thiophenes and benzothiophenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 15241-4.

91. Zhang, J.; Chen, F.; He, Y. M.; Fan, Q. H. Asymmetric ruthenium-catalyzed hydrogenation of 2,6-disubstituted 1,5-naphthyridines: access to chiral 1,5-diaza-cis-decalins. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2015, 54, 4622-5.

92. Kuwano, R.; Sato, K.; Kurokawa, T.; Karube, D.; Ito, Y. Catalytic asymmetric hydrogenation of heteroaromatic compounds, indoles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000, 122, 7614-5.

93. Feiertag, P.; Albert, M.; Nettekoven, U.; Spindler, F. Asymmetric homogeneous hydrogenation of 2,5-disubstituted furans. Org. Lett. 2006, 8, 4133-5.

94. Duan, Y.; Li, L.; Chen, M. W.; Yu, C. B.; Fan, H. J.; Zhou, Y. G. Homogenous Pd-catalyzed asymmetric hydrogenation of unprotected indoles: scope and mechanistic studies. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 7688-700.

95. Chen, Z. P.; Chen, M. W.; Shi, L.; Yu, C. B.; Zhou, Y. G. Pd-catalyzed asymmetric hydrogenation of fluorinated aromatic pyrazol-5-ols via capture of active tautomers. Chem. Sci. 2015, 6, 3415-9.

96. Kuwano, R.; Hashiguchi, Y.; Ikeda, R.; Ishizuka, K. Catalytic asymmetric hydrogenation of pyrimidines. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2015, 54, 2393-6.

97. Chang, M.; Huang, Y.; Liu, S.; et al. Asymmetric hydrogenation of pyridinium salts with an iridium phosphole catalyst. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2014, 53, 12761-4.

98. Masuda, Y.; Tsuda, H.; Murakami, M. Photoinduced dearomatizing three-component coupling of arylphosphines, alkenes, and water. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2021, 60, 3551-5.

99. Meng, Y.; Jian, Y.; Li, J.; et al. Surface-active site engineering: synergy of photo- and supermolecular catalysis in hydrogen transfer enables biomass upgrading and H2 evolution. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 452, 139477.

100. Jian, Y.; Meng, Y.; Li, J.; Wu, H.; Saravanamurugan, S.; Li, H. Engineering oxygen vacancy and crystal surfaces for TiO2-based photocatalysts for enhanced photocatalytic hydrogenation of bio-based carbonyls to biofuels. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2022, 10, 108837.

101. Schwinghammer, K.; Tuffy, B.; Mesch, M. B.; et al. Triazine-based carbon nitrides for visible-light-driven hydrogen evolution. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2013, 52, 2435-9.

102. Sun, Z.; Fujitsuka, M.; Shi, C.; Zhu, M.; Wang, A.; Majima, T. Efficient visible-light-driven hydrogen generation on g-C3N4 coupled with iron phosphide. ChemPhotoChem 2019, 3, 540-4.

103. Zhang, G.; Ling, X.; Liu, G.; et al. Construction of defective zinc-cadmium-sulfur nanorods for visible-light-driven hydrogen evolution without the use of sacrificial agents or cocatalysts. ChemSusChem 2020, 13, 756-62.

104. Teng, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Yang, H.; et al. Atomically dispersed antimony on carbon nitride for the artificial photosynthesis of hydrogen peroxide. Nat. Catal. 2021, 4, 374-84.

105. Sharma, P.; Sasson, Y. A photoactive catalyst Ru–g-C3N4 for hydrogen transfer reaction of aldehydes and ketones. Green. Chem. 2017, 19, 844-52.

106. Yu, J.; Liu, Q.; Qiao, W.; et al. Catalytic role of metal nanoparticles in selectivity control over photodehydrogenative coupling of primary amines to imines and secondary amines. ACS. Catal. 2021, 11, 6656-61.

107. Zhang, D.; Ren, P.; Liu, W.; et al. Photocatalytic abstraction of hydrogen atoms from water using hydroxylated graphitic carbon nitride for hydrogenative coupling reactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2022, 61, e202204256.

108. Han, C.; Han, G.; Yao, S.; et al. Defective ultrathin ZnIn2S4 for photoreductive deuteration of carbonyls using D2O as the deuterium source. Adv. Sci. 2022, 9, e2103408.

109. Yuan, T.; Sun, L.; Wu, Z.; et al. Mild and metal-free Birch-type hydrogenation of (hetero)arenes with boron carbonitride in water. Nat. Catal. 2022, 5, 1157-68.

110. Call, A.; Casadevall, C.; Acuña-Parés, F.; Casitas, A.; Lloret-Fillol, J. Dual cobalt-copper light-driven catalytic reduction of aldehydes and aromatic ketones in aqueous media. Chem. Sci. 2017, 8, 4739-49.

111. Chen, S.; Xi, C. CO2 promoted photoredox/Ni-catalyzed semi-reduction of alkynes with H2O. Green. Chem. 2023, 25, 7978-82.

112. Zhang, M.; Yuan, X. A.; Zhu, C.; Xie, J. Deoxygenative deuteration of carboxylic acids with D2O. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2019, 58, 312-6.

113. Ramirez, N. P.; Gonzalez-Gomez, J. C. Decarboxylative giese-type reaction of carboxylic acids promoted by visible light: a sustainable and photoredox-neutral protocol. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2017, 2017, 2154-63.

114. Zhang, M.; Xie, J.; Zhu, C. A general deoxygenation approach for synthesis of ketones from aromatic carboxylic acids and alkenes. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 3517.

115. Guo, H. M.; Wu, X. Selective deoxygenative alkylation of alcohols via photocatalytic domino radical fragmentations. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 5365.

116. Hasegawa, E.; Seida, T.; Chiba, N.; Takahashi, T.; Ikeda, H. Contrastive photoreduction pathways of benzophenones governed by regiospecific deprotonation of imidazoline radical cations and additive effects. J. Org. Chem. 2005, 70, 9632-5.

117. Naumann, R.; Goez, M. How the sustainable solvent water unleashes the photoredox catalytic potential of ruthenium polypyridyl complexes for pinacol couplings. Green. Chem. 2019, 21, 4470-4.

118. Okumura, S.; Hattori, S.; Fang, L.; Uozumi, Y. Multielectron reduction of esters by a diazabenzacenaphthenium photoredox catalyst. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2024, 146, 16990-5.

119. Flynn, A. R.; McDaniel, K. A.; Hughes, M. E.; Vogt, D. B.; Jui, N. T. Hydroarylation of arenes via reductive radical-polar crossover. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 9163-8.

120. McDaniel, K. A.; Blood, A. R.; Smith, G. C.; Jui, N. T. Dearomatization of unactivated arenes via catalytic hydroalkylation. ACS. Catal. 2021, 11, 4968-72.

121. Geyer, R.; Jambeck, J. R.; Law, K. L. Production, use, and fate of all plastics ever made. Sci. Adv. 2017, 3, e1700782.

122. Borodziński, A.; Bond, G. C. Selective hydrogenation of ethyne in ethene-rich streams on palladium catalysts. Part 1. Effect of changes to the catalyst during reaction. Catal. Rev. 2006, 48, 91-144.

123. Arcudi, F.; Ðorđević, L.; Schweitzer, N.; Stupp, S. I.; Weiss, E. A. Selective visible-light photocatalysis of acetylene to ethylene using a cobalt molecular catalyst and water as a proton source. Nat. Chem. 2022, 14, 1007-12.

124. Nakamura, K.; Nishigaki, H.; Sato, Y. Dual photoredox/cobalt-catalyzed reductive cyclization of alkynals. ACS. Catal. 2024, 14, 3369-75.

125. Huo, H.; Harms, K.; Meggers, E. Catalytic, enantioselective addition of alkyl radicals to alkenes via visible-light-activated photoredox catalysis with a chiral rhodium complex. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 6936-9.

126. Zhong, J. J.; Liu, Q.; Wu, C. J.; et al. Combining visible light catalysis and transfer hydrogenation for in situ efficient and selective semihydrogenation of alkynes under ambient conditions. Chem. Commun. 2016, 52, 1800-3.

127. Zhang, X.; Chen, J.; Gao, Y.; et al. Photocatalyzed transfer hydrogenation and deuteriation of cyclic N-sulfonylimines. Org. Chem. Front. 2019, 6, 2410-4.

128. Liu, P.; Zhao, Y.; Qin, R.; et al. Photochemical route for synthesizing atomically dispersed palladium catalysts. Science 2016, 352, 797-801.

129. Li, T.; Liu, F.; Tang, Y.; et al. Maximizing the number of interfacial sites in single-atom catalysts for the highly selective, solvent-free oxidation of primary alcohols. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2018, 57, 7795-9.

130. Zhang, L.; Long, R.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Direct observation of dynamic bond evolution in single-atom Pt/C3N4 catalysts. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2020, 59, 6224-9.

131. Zhao, Q.; Ni, W.; Tan, X.; et al. A “Trojan horse” strategy towards robust Co–N4 active sites accommodated in micropore defect-rich carbon nanosheets for boosting selective hydrogenation of nitroarenes. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2022, 10, 9435-44.

132. Zhao, E.; Li, M.; Xu, B.; et al. Transfer hydrogenation with a carbon-nitride-supported palladium single-atom photocatalyst and water as a proton source. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2022, 61, e202207410.

133. Jia, T.; Meng, D.; Ji, H.; et al. Visible-light-driven semihydrogenation of alkynes via proton reduction over carbon nitride supported nickel. Appl. Catal. B. Environ. 2022, 304, 121004.

Cite This Article

How to Cite

Download Citation

Export Citation File:

Type of Import

Tips on Downloading Citation

Citation Manager File Format

Type of Import

Direct Import: When the Direct Import option is selected (the default state), a dialogue box will give you the option to Save or Open the downloaded citation data. Choosing Open will either launch your citation manager or give you a choice of applications with which to use the metadata. The Save option saves the file locally for later use.

Indirect Import: When the Indirect Import option is selected, the metadata is displayed and may be copied and pasted as needed.

About This Article

Copyright

Data & Comments

Data

Comments

Comments must be written in English. Spam, offensive content, impersonation, and private information will not be permitted. If any comment is reported and identified as inappropriate content by OAE staff, the comment will be removed without notice. If you have any queries or need any help, please contact us at support@oaepublish.com.