Au particle size manipulated Au/ZnO interface and its performance in selective oxidation of glycerol

Abstract

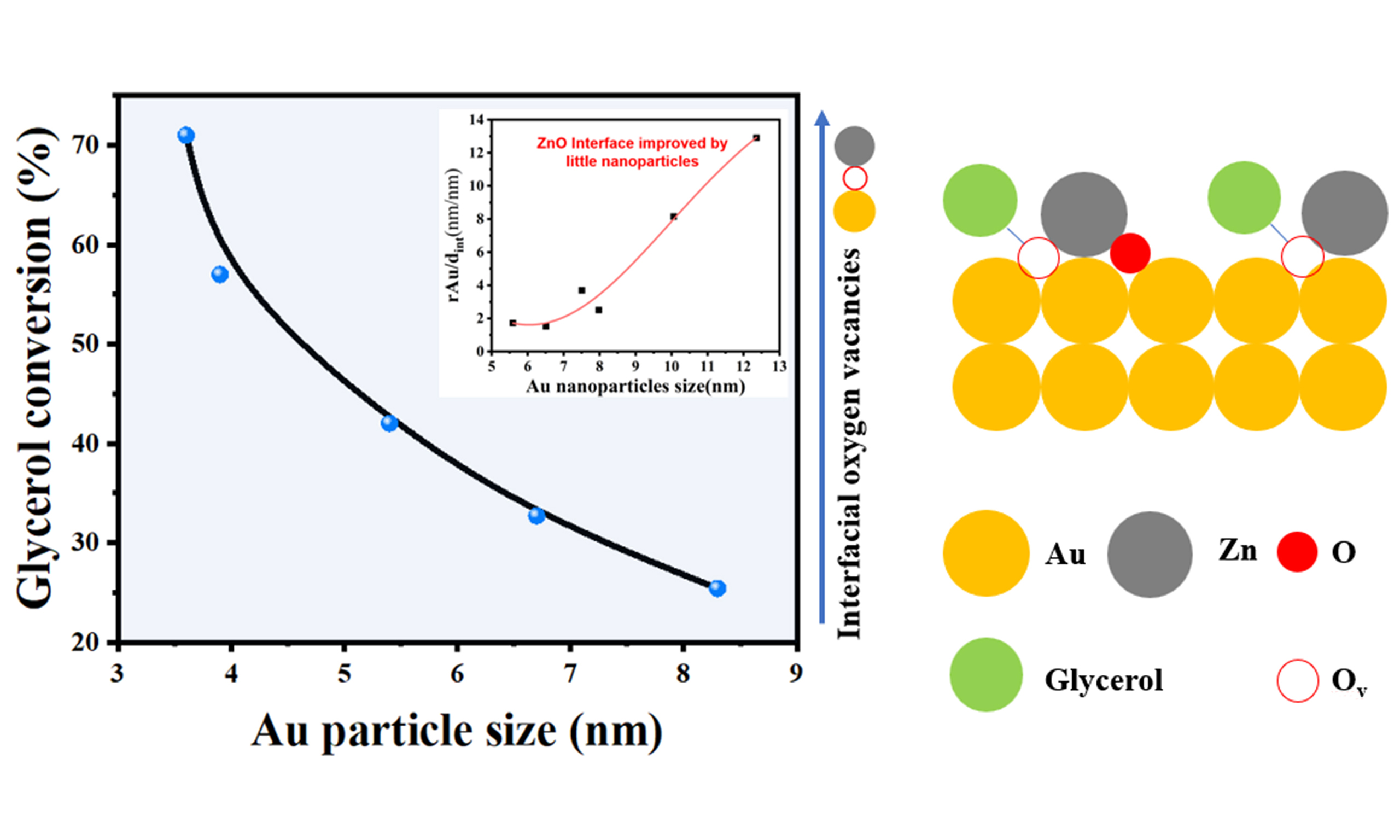

The gold (Au)/oxide interface has been shown to be an effective active site in many oxidation reactions due to its unique structural features. However, several issues arise in research on these active sites, such as the effective control of Au particle size, the correlation between Au particle size and the formation of interface sites, and the promoting effect of effective interface sites on the reaction. In this work, we achieved precise control of Au particle size through a series of methods, and using high-resolution transmission electron microscopy, we demonstrated the correlation between surface energy and the formation of the interface between Au particles and ZnO. Catalyst evaluation results showed that the Au/ZnO interface formed by Au particles of 3.5-4 nm can achieve an approximately 25%-30% increase in glycerol conversion while maintaining the same dihydroxyacetone (DHA) selectivity. We used O 1s X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) and in situ Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) to investigate the mechanism by which oxygen vacancies at the interface promote glycerol selective oxidation. Based on the above results, we conclude that the enhanced activity of the small Au nanoparticles (NPs) originates from the abundance of oxygen vacancies at the Au/ZnO interface. Our studies provide a new insight for the Au particle size manipulated Au/ZnO interface and the performance in hydroxyl oxidation.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

About a decade ago, it was discovered that highly dispersed gold (Au) on oxide supports exhibits significant chemical activity in various reactions[1,2]. As research on Au-based catalysts progressed, it became evident that using suitable oxides as supports in certain reactions can greatly enhance the catalytic activity of Au[3]. For instance, in CO oxidation reactions, the Au/TiO2 interface has been identified as an effective active site[4,5]. Additionally, evidence suggests that the Au perimeter or Au-support interface serves as an active site for other reactions, including the water-gas shift reaction[6], epoxidation of propylene with H2 and O2[7], epoxidation of propene and butene[8,9], and the selective oxidation of propane[10]. Overall, in these various oxidative reactions, Au/oxide systems have played a crucial role in enhancing catalyst performance.

Building on the success of Au/oxide catalysts in oxidative reactions, research has expanded to explore their potential in more complex transformations, such as the selective oxidation of glycerol, a critical process in converting biodiesel by-products into valuable compounds. Glycerol, a by-product of biodiesel production, is increasingly produced and represents an attractive potential precursor for the manufacture of various high-value-added compounds[11]. However, glycerol contains both primary and secondary alcohol groups, leading to the production of various products through its oxidation. Consequently, developing catalysts capable of selectively oxidizing glycerol to obtain specific target products is a considerable challenge[12]. One significant process in the selective oxidation of glycerol is the oxidation of the secondary hydroxyl group to produce dihydroxyacetone (DHA), which has wide applications in the cosmetics, food additives, and livestock industries[13]. In the study of the chemical oxidation of glycerol to DHA, oxide-supported metal catalysts are becoming a primary research focus[14]. Since the preparation of DHA only requires the direct oxidation of the secondary hydroxyl group, it is crucial to consider both the catalytic selectivity and the catalyst’s ability to inhibit further deep oxidation of the aldehyde group.

Among various studies, Au-based catalysts have demonstrated high selectivity in the oxidation of the secondary hydroxyl group. To address the relatively low catalytic activity of Au-based catalysts, various methods have been employed to enhance their catalytic efficiency[15-17]. However, the DHA selectivity decreases when applying Au metal alloys or finely tuning the support’s acid/base properties. Recent studies indicate that glycerol adsorbs onto the surface of oxides during the reaction process, achieving selective oxidation[18]. Therefore, utilizing the metal-support interaction to enhance the performance of Au-based catalysts is a promising approach. In our previous work, we found that the Au/ZnO catalyst obtained after air treatment can serve as an efficient catalyst for the oxidation of glycerol’s secondary hydroxyl group[19]. Based on reaction kinetics analysis and the steady-state approximation study, the results indicate that the oxygen vacancies at the Au/ZnO interface provide specific sites for the adsorption of glycerol’s secondary hydroxyl group. To further investigate the key factors affecting the construction of the Au/ZnO interface, we obtained ZnO supports with different work functions for the preparation of Au/ZnO catalysts[20]. The results show that ZnO supports with high work functions facilitate the formation of the Au/ZnO interface and impart higher positive charges to nanoparticles (NPs). These electron-deficient Au NPs promote the enrichment of OH* and OOH* during the O2 activation process, effectively enhancing the catalytic activity. However, current research still lacks investigation on how to control the content of oxygen vacancies at the Au/ZnO interface. Additionally, the correlation between the content of interface sites in Au/ZnO catalysts and the adsorption capacity of the secondary hydroxyl group of glycerol remains unclear.

In this study, we first established the correlation between Au particle size and ZnO coverage degree. The oxygen vacancy content at the Au/ZnO interface was then altered by controlling the surface energy of Au NPs. Furthermore, we demonstrated that the formation of the Au/ZnO interface is necessary for achieving the selective oxidation of the secondary hydroxyl group. In addition, in situ infrared spectroscopy of glycerol showed that the adsorption capacity of the catalyst for the secondary hydroxyl group is correlated with the oxygen vacancy content at the Au/ZnO interface. This research provides new theoretical support for the development of efficient catalysts for the oxidation of secondary hydroxyl groups.

EXPERIMENTAL

Materials

Chemicals including ZnO, urea, HAuCl4·3H2O, H2PtCl6·6H2O and sodium citrate (C6H5Na3O7) were all of analytical reagent (A.R.) grade and purchased from Aladdin. RuCl3·3H2O of analytical eagent grade was obtained from Macklin. Glycerol with a purity of 98.00 wt.%, sodium borohydride (NaBH4) with a purity of

Preparation of Au/ZnO catalysts

X-Au/ZnO (X = 1, 2, 4, 8)

Gold-loaded catalysts with a metal loading of 4 wt%, including Au/ZnO and AuX/ZnO, were prepared using the urea precipitation-deposition method. The detailed preparation process is as follows. For catalysts with varying deposition times, 1 g of commercial ZnO support was weighed and placed in a 200 mL beaker. Then, 0.3045 mol HAuCl4 and 10.95 g urea were added, followed by 100 mL deionized water. The mixture was ultrasonically dispersed for 3 min, and then magnetically stirred at 450 rpm for 5 min. The beaker was transferred to a water bath at 90 °C and stirred at 450 rpm for 1, 2, 4, and 8 h, respectively. After cooling, the precipitates were washed at least seven times with deionized water to remove Cl- (confirmed by the absence of a white precipitate after adding 50 mmol/L silver nitrate solution). The precipitates were dried in an oven at 60 °C for 8 h, followed by calcination in a muffle furnace at 300 °C for 3 h with a heating rate of 2 °C/min. The resulting catalysts were denoted as X-Au/ZnO (X = 1, 2, 4, 8). The calcination temperature of 300 °C was chosen based on prior studies showing that it promotes optimal interaction between Au and ZnO without excessive sintering.

AuY/ZnO (Y = Pt, Ru)

For catalysts doped with different elements (Y = Pd, Ru), the molar ratio of Au/Y was 10/1, with a urea/metal component ratio of 600/1. The remaining steps were unchanged. The precipitates were washed thoroughly, dried, and calcined as described above, resulting in catalysts denoted as AuY/ZnO (Y = Pd, Ru).

Au/ZnO-4.5

Additionally, an Au/ZnO catalyst was prepared by the sol-immobilization (Sol) method[19]. A 3.47 mL solution of HAuCl4·3H2O was added to 10 mL of PVA solution [PVA/metal (wt./wt.) = 0.8]. After stirring for 10 min, 5 mL of freshly prepared NaBH4 [NaBH4/metal (mol/mol) = 5] was added, forming a dark brown sol. After 30 min, the sol was immobilized on a ZnO support under vigorous stirring. The slurry was filtered after 1 h of immobilization, and the catalyst was washed thoroughly with alcohol and warm distilled water. The precipitate was dried at 60 °C for 8 h, and the Au NP size was confirmed by transmission electron microscopy (TEM), resulting in the Au/ZnO catalyst denoted as Au/ZnO-4.5.

Au/ZnO-21 and Au/ZnO-35

Another series of Au/ZnO catalysts were prepared by the sol-immobilization method using sodium citrate as a reducing agent[21]. A 45 mL aqueous gold salt solution was heated to 80 °C with vigorous stirring for

The catalytic oxidation of glycerol

Experiments were conducted in a glass round-bottomed reaction vessel with a total volume of approximately 50 mL. In a typical reaction, 5 mL of a 0.1 M glycerol solution and a specified amount of catalyst were added to the vessel. The vessel was then purged with O2 for 1 min and operated under 0.1 MPa pure O2. The glycerol/Au molar ratio was maintained at 100. The reaction vessel was placed on a preheated device at 80 °C and magnetically stirred at 800 rpm. For reaction time screening experiments, the reaction time was varied from 1 to 8 h, while for all other experiments it was fixed at 4 h. After completion, the reaction vessel was immediately quenched in cold water, and the solid catalyst was separated by centrifugation.

Product analysis was performed using a Shimadzu high-performance liquid chromatograph (HPLC) equipped with a Zorbax SAX column, ultraviolet (UV) detection at 220 nm, and refractive index detection. Separation was carried out at 31 °C using a 0.1 wt.% H3PO4 aqueous solution (flow rate of 0.2 mL/min) and pure acetonitrile (flow rate of 0.4 mL/min) as the eluent. Quantification was achieved using an external calibration method.

GL conversion (%) = M(converted GLY) / M(GLY in feed) × 100;

DHA selectivity (%) = M(DHA) / M(converted GLY) × 100;

where GLY stands for glycerol.

Catalysts characterization

The powder X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns of the Au/ZnO catalysts were recorded using a Shimadzu XRD-600 X-ray diffractometer (Shimadzu Corporation, Kyoto, Japan). High-resolution TEM (HRTEM) micrographs were obtained with a JEOL JEM-2100F microscope (JEOL Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) was recorded on a Thermo VG ESCALAB 250 spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) equipped with an Al Kα anode, using a C 1s peak at 284.6 eV for calibration. Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) was collected with a Bruker Vector 22 Fourier transform infrared spectrometer (Bruker Optics GmbH, Ettlingen, Germany). In situ FTIR spectra of CO were recorded using a Bruker Tensor 27 Fourier transform infrared spectrometer with a mercury-cadmium-telluride (MCT) detector. A 10 mm diameter disc containing 25 mg of Au/ZnO catalyst was loaded into a cell with a BaF2 window and pretreated in a helium atmosphere (flow rate of 30 mL/min, heating rate of 10 °C/min) at 120 °C for 60 min. At 20 °C, a background spectrum was collected at a resolution of 4 cm-1. Then, 99.9 vol.% CO was introduced for 30 min.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Catalysts preparation

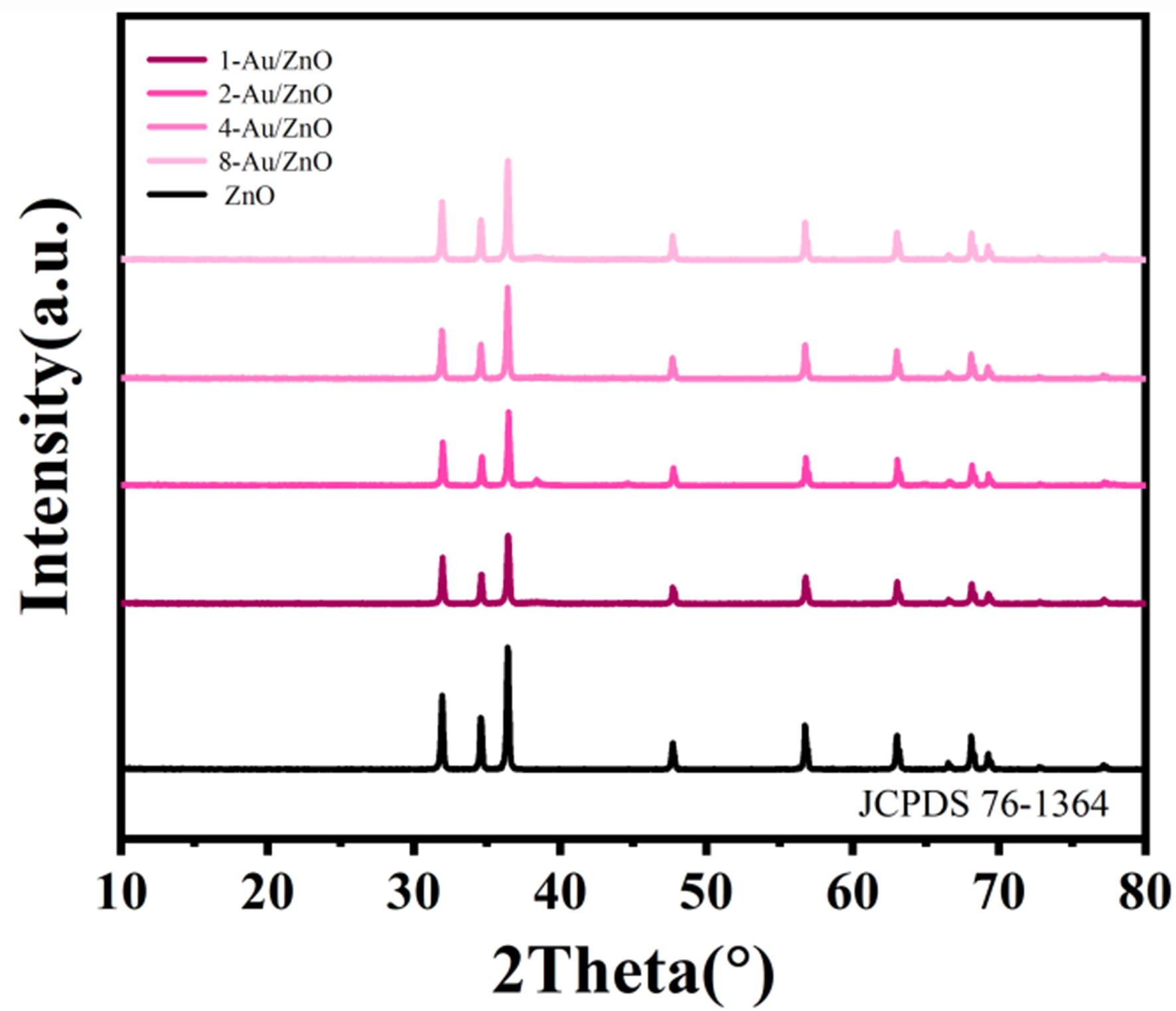

In numerous reactions, the particle size of Au catalysts significantly influences their performance. The deposition-precipitation method is an effective approach for obtaining Au particles with uniform size, where urea plays a crucial role as the precipitating agent in the preparation of Au catalysts. Zanella et al. demonstrated that the precipitation and deposition process of gold salt solution using urea (DPU) as a precipitant evolves similarly to a peptization process[22]. The deposition of Au species occurs through the formation of amorphous precipitates, resulting from the reaction between hydroxyl chloride-Au (III) and urea decomposition products. By leveraging the peptization phenomenon of Au salt on ZnO, a series of Au/ZnO catalysts were prepared by varying the Au deposition time. The powder XRD spectra of the prepared X-Au/ZnO catalyst are shown in Figure 1. According to the standard card (JCPDS 76-1364), ZnO is identified as a hexagonal wurtzite ZnO species with good crystallinity[23,24]. The crystallinity of ZnO decreased after Au deposition, indicating an emerging metal-support interaction in Au/ZnO[25]. Additionally, the standard XRD diffraction peak of Au (04-0784) was not observed in the range of 10°-80°, suggesting that high dispersion of Au species can be achieved using the DPU method.

Relationship between metal surface energy and overlayer content

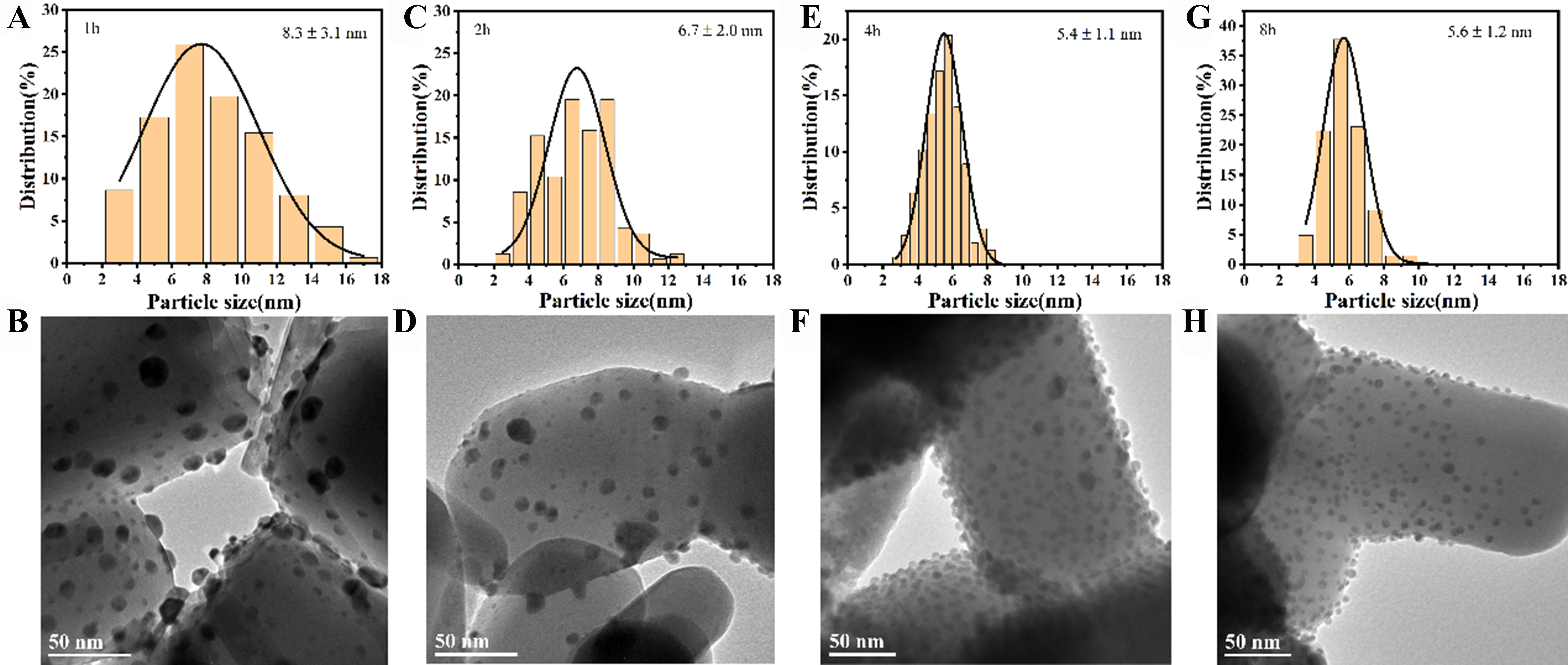

HRTEM was employed to investigate the size of Au NPs. As shown in Figure 2A and B, the size range of Au NPs in 1-Au/ZnO is 2-18 nm, with an average particle size of 8.3 ± 3.1 nm. For the 2-Au/ZnO catalyst

Figure 2. HRTEM pictures of Au/ZnO catalysts with different precipitation deposition times, (A and B) deposition 1 h; (C and D) deposition 2 h; (E and F) deposition 4 h; (G and H) deposition 8 h. HRTEM: High-resolution transmission electron microscopy.

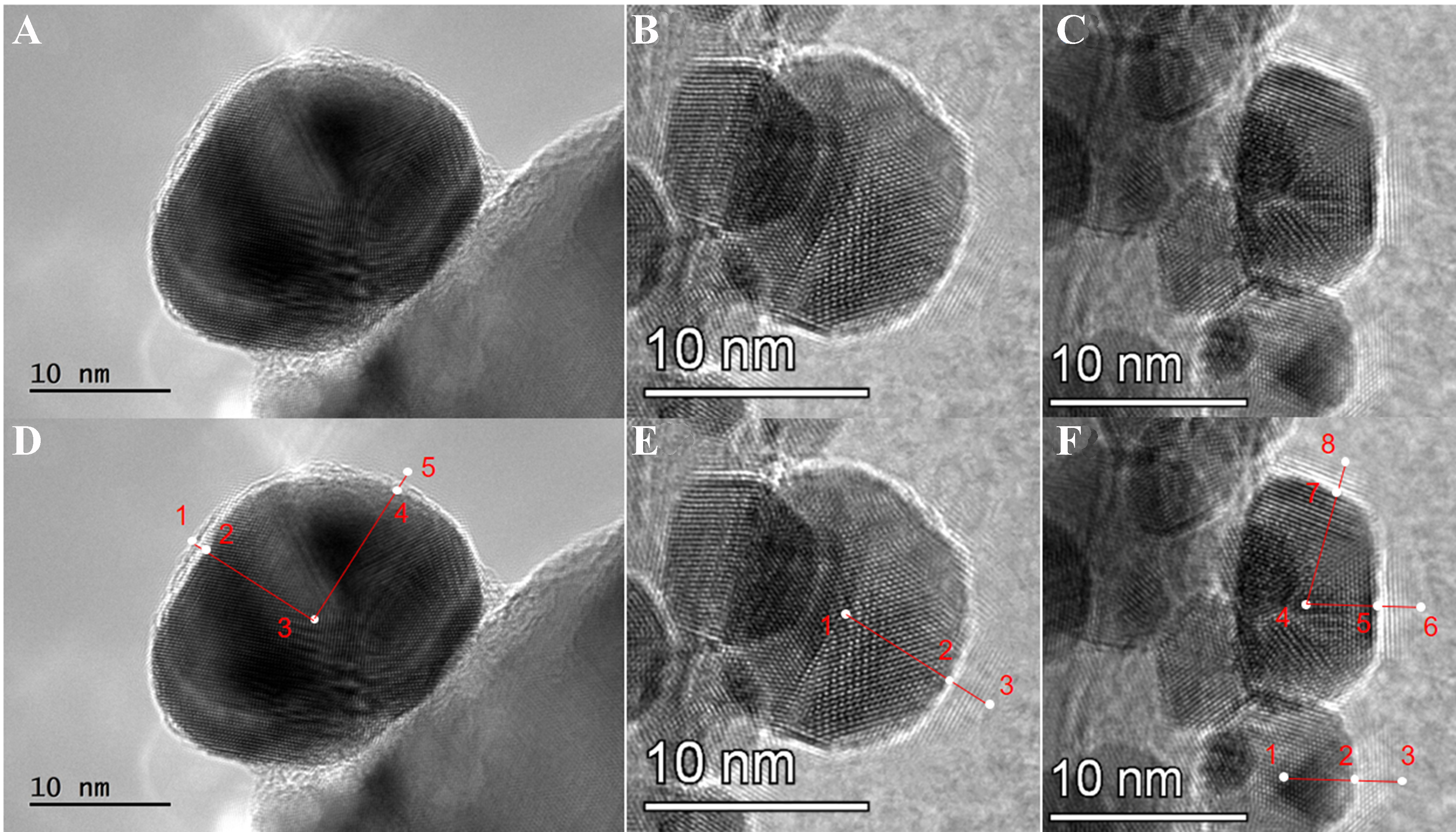

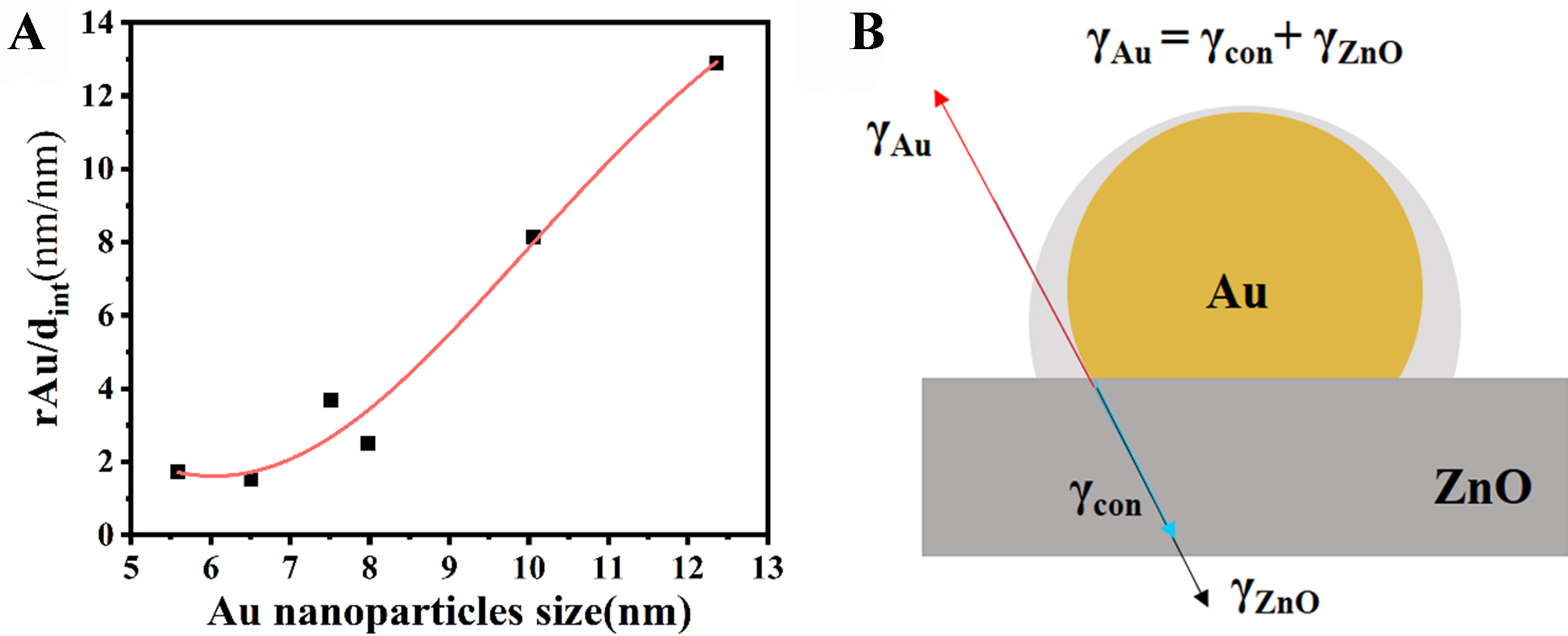

Further, the X-Au/ZnO catalysts were studied under high resolution. As shown in Figure 3A-C, Au NPs of various sizes were selected, revealing an overlayer with a specific interplanar spacing around the Au NPs. This interplanar spacing measures 0.269 nm and is comparable to that of ZnO (101)[26,27], indicating that the overlayer is composed of ZnO species. In Figure 3D, several key distances are defined: R13 represents the distance from the outermost interface layer to the center of the Au NP, while R12 and R23 denote the thickness of the interface layer and the radius of the Au NP, respectively. The values of these distances vary across different NPs; for example: R13 = 10.06 nm, R23/R12 = 8.145. The remaining Figure 3E and F was also analyzed using the same method. As shown in Figure 4A, the Au particle size increases as the thickness of the overlayer decreases, indicating that the thickness of the interface layer is influenced by the Au NP size. It has been reported that the coverage of active components by the formation of the support is primarily controlled by the surface energy of each component of the catalyst[28]. In this system, the process by which Au is coated with ZnO is similar to the process in which small solid particles are infiltrated by another substance. According to the balance formula of surface tension [Equation (1)][29], Figure 4B depicts the surface energy of Au (γAu) and the surface energy of the ZnO coating (γcon) in an Au/ZnO catalyst that has formed an interface structure, in equilibrium with the surface energy of ZnO (γZnO) at a specific point. Many researchers have studied in detail the relationship between nanoscale particle size and surface tension[30-34]. The gas-solid surface energy γsv (D) change corresponding to the size effect can be simplified and discussed using Equation (2)[29], where the diameter of the Au NP is defined as D, and the value of C varies in different models. It can be seen from the formula that when C is negative, the value of γsv (D) decreases as the particle size increases.

Figure 3. (A-C) HRTEM images of Au NPs with different sizes and interface sizes in Au/ZnO catalysts; (D-F) the measured distance of the particle and the overlayer. HRTEM: High-resolution transmission electron microscopy; NPs: nanoparticles.

Figure 4. (A) Relationship between Au NPs of different sizes and interface distance in Au/ZnO catalyst; (B) Mechanism of Au, ZnO interface and ZnO at a certain point of surface energy equilibrium. NPs: Nanoparticles.

In the Au/ZnO system, the results show that the overlayer thickness decreases as the size of Au NPs increases. Thus, smaller Au NPs increase surface tension, promoting the formation of a more substantial ZnO overlayer. During the air heat treatment of Au/ZnO, ZnO tends to cover the surface of the Au NPs to reduce the overall surface energy of the catalyst. This process is a potential driving force for the formation of the interface structure. Therefore, it can be inferred that increasing the overall surface energy of the active component can effectively promote the construction of the interface structure.

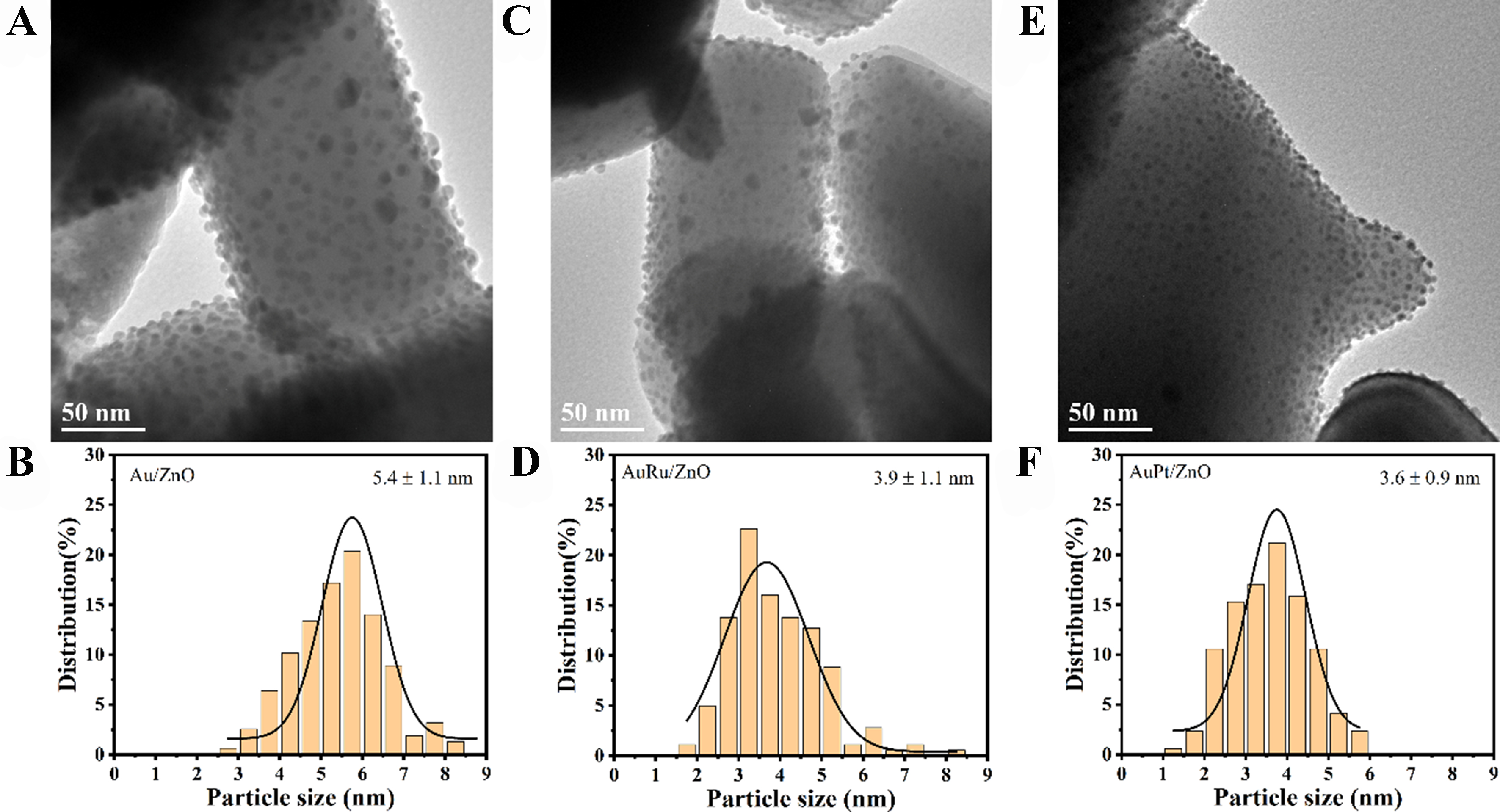

In Table 1, the theoretical surface energy of the Au (111) crystal plane is higher than the surface energy of ZnO, resulting in ZnO having a wetting effect on Au. Further experiments were conducted by introducing a small amount of another metal (Au:X = 10:1). As shown in Figure 5, introducing a small amount of metal with high surface energy (> 1.5 J/m2) during the precipitation deposition process reduced the size of Au NPs from 5.4 ± 1.1 nm (Au/ZnO, Figure 5A and B) to 3.9 ± 1.1 nm (AuRu/ZnO, Figure 5C and D) and 3.6 ±

Figure 5. HRTEM pictures and particle size distribution histograms of Au/ZnO catalysts with different metal compositions: (A and B) Au/ZnO, (C and D) AuRu/ZnO and (E and F) AuPt/ZnO. HRTEM: High-resolution transmission electron microscopy.

The surface energy of different metals and ZnO, J/m-2

| Element | γsvPa | γsvEb |

| Au (111) | 1.52 | 1.51 |

| Pd (111) | 1.85 | 2.00 |

| Ru (0001) | 1.70 | - |

| Pt (111) | 2.54 | 2.49 |

| Ag (111) | 1.20 | 1.25 |

| ZnO | 1.33 | - |

Glycerol oxidation

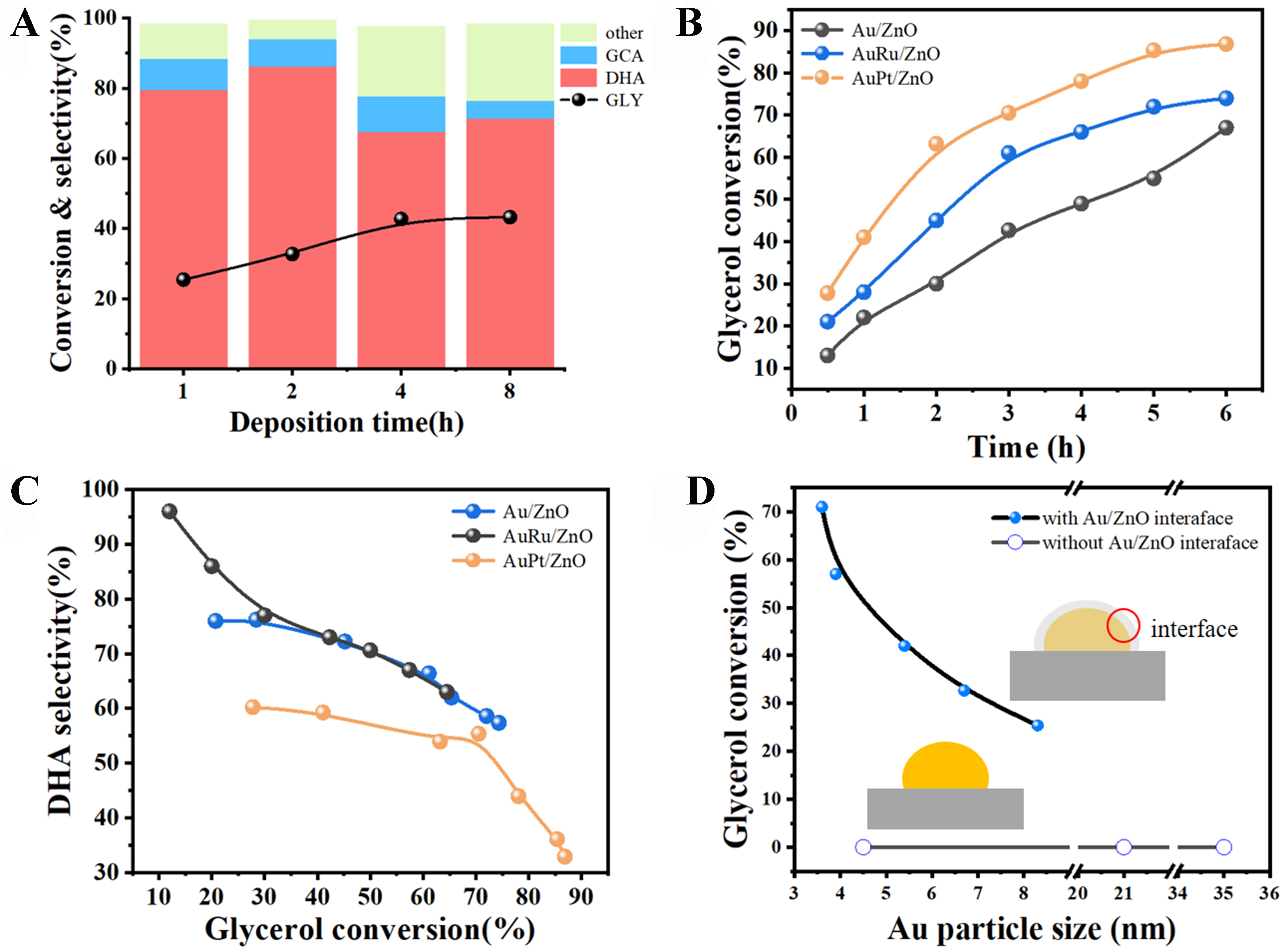

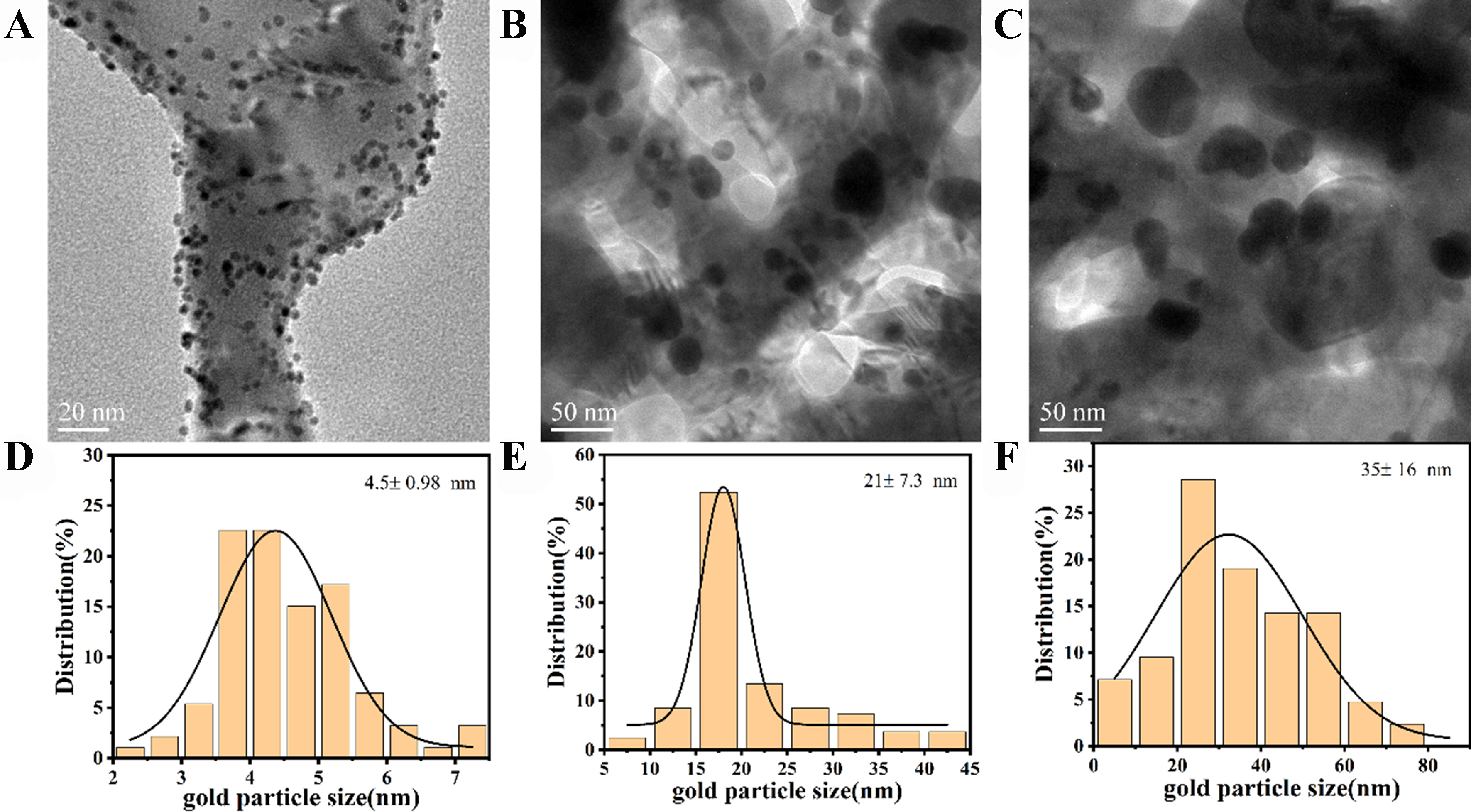

X-Au/ZnO catalysts with varying precipitation and deposition times, as well as AuX/ZnO catalysts doped with a second metal, were employed for the selective oxidation of glycerol. As illustrated in Figure 6A, the catalytic activity improves with increased precipitation and deposition time of the active components. Furthermore, introducing a second metal component to the Au catalyst significantly enhances its performance, as shown in Figure 6B. The order of catalyst activity is AuPt/ZnO > AuRu/ZnO > 4-Au/ZnO. In Figure 6C, both Au/ZnO and AuRu/ZnO exhibit similar changes in DHA selectivity with glycerol conversion. However, at the same conversion rate, the DHA selectivity of the AuPt/ZnO catalyst decreases to some extent, possibly due to excessive oxidation or strong adsorption of DHA on Pt species[39-41]. It has been reported that the catalytic activity of Au-based catalysts is often related to the size of Au NPs[42,43]. To further investigate the correlation between Au NP size and catalyst activity, Au/ZnO catalysts with different NP sizes and without a ZnO coating layer were prepared. The HRTEM results for the Au/ZnO catalyst are presented in Figure 7A-C, showing that these catalysts lack catalytic activity. The Au/ZnO catalysts of varying sizes [Figure 7D-F], prepared via the non-atmosphere reduction method, did not exhibit glycerol oxidation performance [Figure 6D]. This indicates that changes in Au NP size are not the primary factor affecting the performance of Au/ZnO catalysts. Instead, the significant correlation lies in the interface structure between the ZnO coating and the Au/ZnO catalyst.

Figure 6. (A) Catalytic performance of X-Au/ZnO with different deposition times; (B) Au/ZnO, AuRu/ZnO, AuPt/ZnO catalyst conversion rate vs. time; (C) Au/ZnO, AuRu/ZnO, AuPt/ZnO catalyst selectivity vs. time curve.

Electronic state of Au

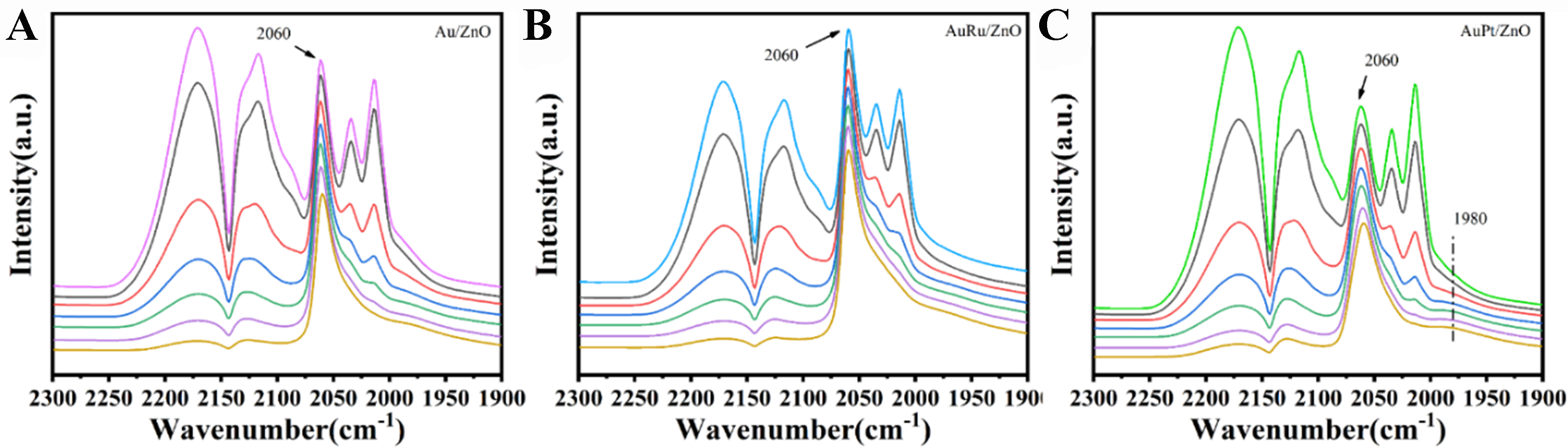

Using in situ FTIR spectroscopy of CO, the electronic structure and adsorption capacity of Au NPs were investigated [Figure 8]. Spectra for Au/ZnO, AuRu/ZnO, and AuPt/ZnO were recorded starting from the saturated CO adsorption peaks, with intervals of 15 s. All three catalysts exhibited CO gas-phase adsorption peaks in the range of 2,100-2,200 cm-1. Given that the CO used was of high purity (99.9 vol.%), the peaks observed at 2,015 and 2,030 cm-1, which disappeared upon inert gas purging, can also be attributed to physically adsorbed CO. Additionally, all three catalysts displayed a CO adsorption peak at 2,060 cm-1, corresponding to the linear adsorption of CO on the edge/step sites of Au NPs[44,45]. The absence of peak shifts with decreasing CO coverage indicates similar electronic environments for Au across the three catalysts. In AuPt/ZnO, a vibrational adsorption peak for the carbonyl species Au(CO)2 at 1,980 cm-1 was observed, corresponding to the νsym and νasym vibrations[46]. The alloyed AuPt/ZnO demonstrated enhanced adsorption capacity for carbonyl species, implying a similarly increased adsorption capacity for the C=O bond in DHA. During the reaction, the strong adsorption of DHA on AuPt/ZnO leads to its oxidation, resulting in lower DHA selectivity for AuPt/ZnO compared to Au/ZnO and AuRu/ZnO at the same conversion rate.

Figure 8. In situ FTIR spectra of CO adsorption on (A) Au/ZnO, (B) AuRu/ZnO, and (C) AuPt/ZnO catalysts. In each panel, the CO adsorption spectra were collected at 30 s intervals and are arranged from bottom to top; the topmost spectrum corresponds to saturated CO adsorption. FTIR: Fourier transform infrared.

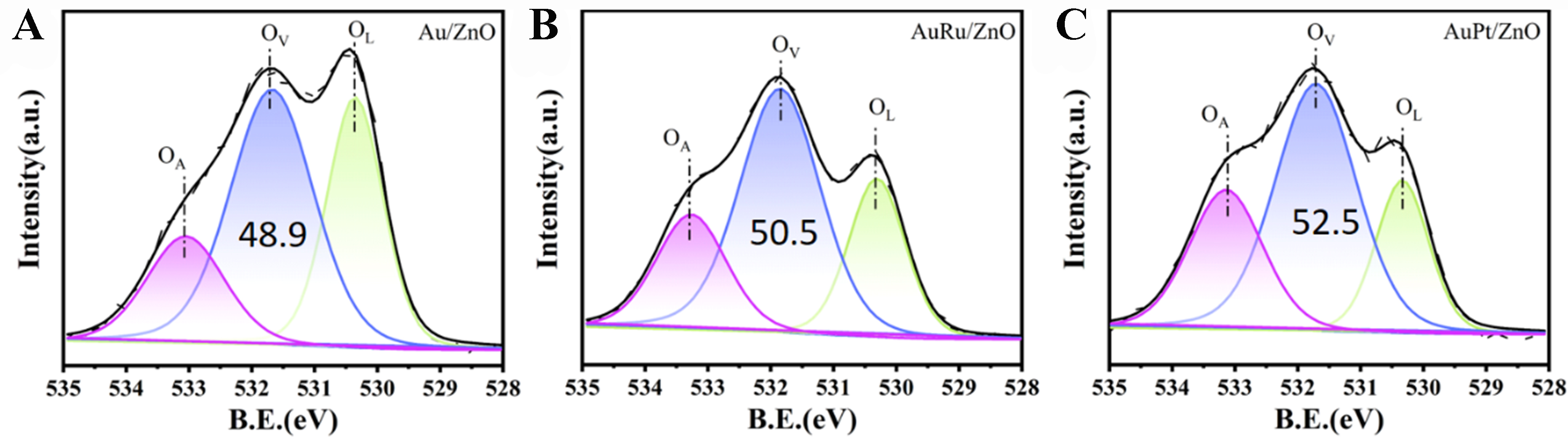

Oxygen defects

Figure 9A-C shows the O 1s XPS spectra of the catalysts. The peak at 533.5 eV (OA) can be attributed to the weak adsorption peak of chemically or dissociatively adsorbed O or OH species on the ZnO surface[47]. The peak at 531.8 eV (OV) is attributed to oxygen vacancy defects[48], and the peak in the lower electron binding energy region at 530.3 eV corresponds to the characteristic peak of ZnO lattice oxygen (OL)[49]. The O 1s spectra of the three catalysts were semi-quantitatively analyzed. The content of oxygen vacancies in the three catalysts is as follows: AuPt/ZnO (52.5%) > AuRu/ZnO (50.5%) > Au/ZnO (48.9%). This result indicates that the introduction of a second metal component into Au increases the oxygen vacancy content of the catalyst. Additionally, particle size analysis of the catalysts showed that AuPt/ZnO (3.6 nm) < AuRu/ZnO (3.9 nm) < Au/ZnO (5.4 nm). As observed in Figure 4A, the Au particle size is inversely proportional to the content of overlayers. Therefore, incorporating high-energy components (Pt, Ru) into Au can increase the ZnO overlayer content by reducing the size of Au NPs, leading to the formation of more oxygen defects.

In situ infrared spectroscopy of glycerol and reaction mechanism

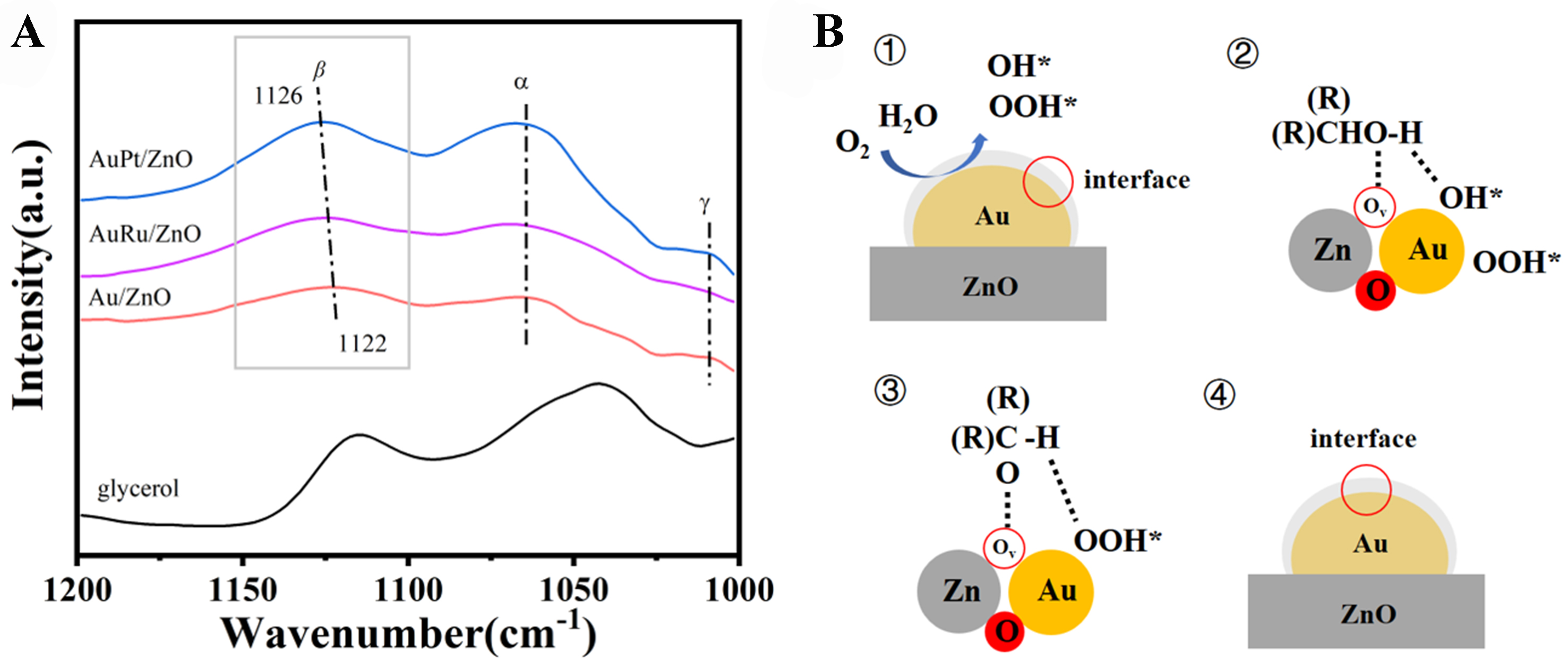

In situ infrared spectroscopy was utilized to investigate the adsorption state of glycerol on the catalyst surface. Initially, the spectrum of pure glycerol was measured, as depicted in Figure 10A, revealing characteristic peaks at 1,116 and 1,040 cm-1. Following the introduction of glycerol onto the catalyst, the final adsorption spectrum was obtained by removing physically adsorbed glycerol molecules through vacuum extraction. The adsorption peaks of glycerol on metal oxides can be classified into three types[18,50]. The peak at the highest wavenumber corresponds to the adsorption of secondary hydroxyl groups, while the intermediate and lower wavenumber peaks correspond to the adsorption of the two primary alcohol groups of glycerol on the catalyst. Given that the initial wavenumber for the 2-OH group in glycerol is 1,115 cm-1, the prominent peak shift suggests significant electronic interaction between the 2-OH group and the Au/ZnO interface. The adsorption peak of the secondary alcohol shifts from 1,122 to 1,126 cm-1 on Au/ZnO, AuRu/ZnO, and AuPt/ZnO, indicating stronger adsorption of the secondary alcohol on AuPt/ZnO and weaker adsorption on Au/ZnO. Meanwhile, the adsorption peaks of primary alcohol groups on Au/ZnO, AuRu/ZnO, and AuPt/ZnO catalysts remain consistent, suggesting that the introduction of Pt and Ru does not affect the adsorption behavior of primary alcohol groups on the catalyst. Therefore, introducing a second component with higher surface energy during the precipitation deposition process of Au species enables the controlled preparation of Au NPs in Au/ZnO catalysts with specific interfacial structures. The formation of small-sized Au NPs facilitates the creation of vacancy-rich ZnO overlayers, ultimately enhancing the catalytic activity by increasing the adsorption strength of glycerol’s secondary hydroxyl groups on the catalyst.

Figure 10. (A) In situ FTIR spectra of adsorbed glycerol of Au/ZnO, AuRu/ZnO and AuPt/ZnO catalysts; (B) possible reaction mechanism of Au/ZnO catalysts. FTIR: Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy.

In the Au/ZnO system, a plausible reaction mechanism is proposed. As illustrated in Figure 10B, molecular oxygen (O2) dissociates on the Au NPs, forming atomic oxygen (O*). This atomic oxygen then reacts with water (H2O) to create peroxide (OOH*) and hydroxyl (OH*) species. Concurrently, the secondary hydroxyl group of glycerol adsorbs onto the oxygen vacancies at the Au/ZnO interface. In the subsequent step, the hydroxyl (OH*) on Au reacts with the hydrogen in the secondary hydroxyl group of glycerol to produce water. The OOH* on Au then cleaves the β-hydrogen of glycerol, resulting in the formation of DHA and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), a rate-limiting step in the reaction. Finally, DHA and H2O2 desorb from the active site, returning the reaction sites to their initial state. The abundant surface oxygen vacancies significantly improve the activation of the secondary hydroxyl groups of glycerol. Consequently, Au/ZnO with small Au NPs and a high concentration of oxygen defects exhibits superior catalytic performance.

CONCLUSIONS

This work elucidates the intrinsic correlation between Au nanoparticle size and the extent of the ZnO overlayer. By doping Au with high–surface-energy elements, we achieved precise control over Au particle size, accompanied by a concomitant increase in ZnO overlayer coverage. The improved catalytic performance is ascribed to particle-size–induced modulation of the surface ZnO overlayer and its associated oxygen vacancies, which enhances the adsorption of secondary hydroxyl groups and facilitates their selective oxidation. Overall, this study demonstrates that the Au/ZnO interfacial structure can be rationally tailored via particle-size engineering, providing an effective strategy for designing high-performance, size-controlled Au-based catalysts for the selective oxidation of secondary hydroxyl groups in alcohols.

DECLARATIONS

Authors’ contributions

Conceived the idea and led the project: Han, Y.; He, Y.; Li, D.

Designed the samples and performed experiments: Han, Y.; Wu, G.; Jiang, Y.

Analyzed the data and wrote the paper: Han, Y.; Wu, G.; Jiang, Y.; Hu, Z. Y.; He, Y.; Li, D.

Gave the HRTEM support and advice: Hu, Z. Y.

Provided the experimental guidance and advice: He, Y.; Li, D.

All authors contributed to the general discussion.

Availability of data and materials

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Financial support and sponsorship

This work was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (No. 2022YFA1506200) and the Natural Science Foundation of China (U23B20164, 22078007, 52103285, 22408361).

Conflicts of interest

All authors declared that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026.

REFERENCES

1. Hvolbæk, B.; Janssens, T. V.; Clausen, B. S.; Falsig, H.; Christensen, C. H.; Nørskov, J. K. Catalytic activity of Au nanoparticles. Nano. Today. 2007, 2, 14-8.

2. Ishida, T.; Murayama, T.; Taketoshi, A.; Haruta, M. Importance of size and contact structure of gold nanoparticles for the genesis of unique catalytic processes. Chem. Rev. 2020, 120, 464-525.

3. Liu, X. Y.; Wang, A.; Zhang, T.; Mou, C. Catalysis by gold: new insights into the support effect. Nano. Today. 2013, 8, 403-16.

4. Yuan, W.; Zhu, B.; Fang, K.; et al. In situ manipulation of the active Au-TiO2 interface with atomic precision during CO oxidation. Science 2021, 371, 517-21.

5. Huang, J.; He, S.; Goodsell, J. L.; et al. Manipulating atomic structures at the Au/TiO2 interface for O2 activation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 6456-60.

6. Mendes, D.; Garcia, H.; Silva, V. B.; Mendes, A.; Madeira, L. M. Comparison of nanosized gold-based and copper-based catalysts for the low-temperature water-gas shift reaction. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2009, 48, 430-9.

7. Hayashi, T.; Tanaka, K.; Haruta, M. Selective vapor-phase epoxidation of propylene over Au/TiO2catalysts in the presence of oxygen and hydrogen. J. Catal. 1998, 178, 566-75.

8. Jiang, J.; Kung, H. H.; Kung, M. C.; Ma, J. Aqueous phase epoxidation of 1-butene catalyzed by suspension of Au/TiO2 + TS-1. Gold. Bull. 2009, 42, 280-7.

9. Jiang, J.; Oxford, S. M.; Fu, B.; Kung, M. C.; Kung, H. H.; Ma, J. Isotope labelling study of CO oxidation-assisted epoxidation of propene. Implications for oxygen activation on Au catalysts. Chem. Commun. 2010, 46, 3791-3.

10. Bravo-Suárez, J. J.; Bando, K. K.; Akita, T.; Fujitani, T.; Fuhrer, T. J.; Oyama, S. T. Propane reacts with O2 and H2 on gold supported TS-1 to form oxygenates with high selectivity. Chem. Commun. 2008, 3272-4.

11. Hu, X.; Lu, J.; Liu, Y.; Chen, L.; Zhang, X.; Wang, H. Sustainable catalytic oxidation of glycerol: a review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2023, 21, 2825-61.

12. Yang, L.; Li, X.; Chen, P.; Hou, Z. Selective oxidation of glycerol in a base-free aqueous solution: a short review. Chinese. J. Catal. 2019, 40, 1020-34.

13. Belfleur, L.; Sonavane, M.; Hernandez, A.; Gassman, N. R.; Migaud, M. E. Solution chemistry of dihydroxyacetone and synthesis of monomeric dihydroxyacetone. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2022, 35, 616-25.

14. Walgode, P. M.; Faria, R. P. V.; Rodrigues, A. E. A review of aerobic glycerol oxidation processes using heterogeneous catalysts: a sustainable pathway for the production of dihydroxyacetone. Catal. Rev. 2021, 63, 422-511.

15. Shen, Y.; Li, Y.; Liu, H. Base-free aerobic oxidation of glycerol on TiO2-supported bimetallic Au–Pt catalysts. J. Energy. Chem. 2015, 24, 669-73.

16. Jouve, A.; Nagy, G.; Somodi, F.; et al. Gold-silver catalysts: effect of catalyst structure on the selectivity of glycerol oxidation. J. Catal. 2018, 368, 324-35.

17. Wang, Y.; Pu, Y.; Yuan, D.; et al. Selective oxidation of glycerol to dihydroxyacetone over Au/CuxZr1-xOy catalysts in base-free conditions. ACS. Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2019, 11, 44058-68.

18. Copeland, J. R.; Shi, X. R.; Sholl, D. S.; Sievers, C. Surface interactions of C2 and C3 polyols with γ-Al2O3 and the role of coadsorbed water. Langmuir 2013, 29, 581-93.

19. Pan, Y.; Wu, G.; He, Y.; Feng, J.; Li, D. Identification of the Au/ZnO interface as the specific active site for the selective oxidation of the secondary alcohol group in glycerol. J. Catal. 2019, 369, 222-32.

20. Wu, G.; Zhao, G.; Sun, J.; et al. The effect of oxygen vacancies in ZnO at an Au/ZnO interface on its catalytic selective oxidation of glycerol. J. Catal. 2019, 377, 271-82.

21. Zhang, Z.; Chen, H.; Xing, C.; et al. Sodium citrate: a universal reducing agent for reduction/decoration of graphene oxide with Au nanoparticles. Nano. Res. 2011, 4, 599-611.

22. Zanella, R.; Delannoy, L.; Louis, C. Mechanism of deposition of gold precursors onto TiO2 during the preparation by cation adsorption and deposition–precipitation with NaOH and urea. Appl. Catal. A. Gen. 2005, 291, 62-72.

23. Singh, P.; Kumar, A.; Kaushal, A.; Kaur, D.; Pandey, A.; Goyal, R. N. In situ high temperature XRD studies of ZnO nanopowder prepared via cost effective ultrasonic mist chemical vapour deposition. Bull. Mater. Sci. 2008, 31, 573-7.

24. Ristić, M.; Musić, S.; Ivanda, M.; Popović, S. Sol–gel synthesis and characterization of nanocrystalline ZnO powders. J. Alloys. Compd. 2005, 397, L1-4.

25. Liu, M.; Chen, Y.; Liu, X.; Kuo, J.; Chu, M.; Mou, C. Defect-mediated gold substitution doping in ZnO mesocrystals and catalysis in CO oxidation. ACS. Catal. 2016, 6, 115-22.

26. Yurieva, T. M.; Plyasova, L. M.; Zaikovskii, V. I.; et al. In situ XRD and HRTEM studies on the evolution of the Cu/ZnO methanol synthesis catalyst during its reduction and re-oxidation. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2004, 6, 4522.

27. Wang, X.; Li, Q.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, J.; Liu, Z.; Wang, R. Low-temperature growth and properties of ZnO nanowires. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2004, 84, 4941-3.

28. Fu, Q.; Wagner, T.; Olliges, S.; Carstanjen, H. D. Metal-oxide interfacial reactions: encapsulation of Pd on TiO2 (110). J. Phys. Chem. B. 2005, 109, 944-51.

29. Du, X.; Huang, Y.; Pan, X.; et al. Size-dependent strong metal-support interaction in TiO2 supported Au nanocatalysts. Nat. Commum. 2020, 11, 5811.

30. Jiang, Q.; Lu, H. Size dependent interface energy and its applications. Surf. Sci. Rep. 2008, 63, 427-64.

31. Jiang, Q.; Lu, H. M.; Zhao, M. Modelling of surface energies of elemental crystals. J. Phys. Condens. Matter. 2004, 16, 521-30.

32. Xiong, S.; Qi, W.; Cheng, Y.; Huang, B.; Wang, M.; Li, Y. Modeling size effects on the surface free energy of metallic nanoparticles and nanocavities. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2011, 13, 10648-51.

33. Guenther, G.; Guillon, O. Models of size-dependent nanoparticle melting tested on gold. J. Mater. Sci. 2014, 49, 7915-32.

34. Samsonov, V. M.; Chernyshova, A. A.; Sdobnyakov, N. Y. Size dependence of the surface energy and surface tension of metal nanoparticles. Bull. Russ. Acad. Sci. Phys. 2016, 80, 698-701.

35. Chou, M. Y.; Chelikowsky, J. R. First-principles study of hydrogen adsorption on Ru(0001): possible occupation of subsurface sites. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1987, 59, 1737-40.

36. Xu, F.; Zhang, P.; Navrotsky, A.; et al. Hierarchically assembled porous ZnO nanoparticles: synthesis, surface energy, and photocatalytic activity. Chem. Mater. 2007, 19, 5680-6.

37. Tyson, W.; Miller, W. Surface free energies of solid metals: estimation from liquid surface tension measurements. Surf. Sci. 1977, 62, 267-76.

38. Aqra, F.; Ayyad, A. Surface energies of metals in both liquid and solid states. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2011, 257, 6372-9.

39. Kimura, H.; Tsuto, K.; Wakisaka, T.; Kazumi, Y.; Inaya, Y. Selective oxidation of glycerol on a platinum-bismuth catalyst. Appl. Catal. A. Gen. 1993, 96, 217-28.

40. Garcia, R.; Besson, M.; Gallezot, P. Chemoselective catalytic oxidation of glycerol with air on platinum metals. Appl. Catal. A. Gen. 1995, 127, 165-76.

41. Katryniok, B.; Kimura, H.; Skrzyńska, E.; et al. Selective catalytic oxidation of glycerol: perspectives for high value chemicals. Green. Chem. 2011, 13, 1960.

42. D’Agostino, C.; Brett, G.; Divitini, G.; et al. Increased affinity of small gold particles for glycerol oxidation over Au/TiO2 probed by NMR relaxation methods. ACS. Catal. 2017, 7, 4235-41.

43. D’agostino, C.; Armstrong, R. D.; Hutchings, G. J.; Gladden, L. F. Product inhibition in glycerol oxidation over Au/TiO2 catalysts quantified by NMR relaxation. ACS. Catal. 2018, 8, 7334-9.

44. Bailie, J. E.; Abdullah, H. A.; Anderson, J. A.; et al. Hydrogenation of but-2-enal over supported Au/ZnO catalysts. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2001, 3, 4113-21.

45. Luo, J.; Liu, Y.; Niu, Y.; et al. Insight into the chemical adsorption properties of CO molecules supported on Au or Cu and hybridized Au-CuO nanoparticles. Nanoscale 2017, 9, 15033-43.

46. Rogers, S. M.; Catlow, C. R. A.; Chan-Thaw, C. E.; et al. Tailoring gold nanoparticle characteristics and the impact on aqueous-phase oxidation of glycerol. ACS. Catal. 2015, 5, 4377-84.

47. Al-Gaashani, R.; Radiman, S.; Daud, A.; Tabet, N.; Al-Douri, Y. XPS and optical studies of different morphologies of ZnO nanostructures prepared by microwave methods. Ceram. Int. 2013, 39, 2283-92.

48. Tabet, N.; Faiz, M.; Al-oteibi, A. XPS study of nitrogen-implanted ZnO thin films obtained by DC-Magnetron reactive plasma. J. Electron. Spectrosc. Relat. Phenom. 2008, 163, 15-8.

49. Velu, S.; Suzuki, K.; Gopinath, C. S.; Yoshida, H.; Hattori, T. XPS, XANES and EXAFS investigations of CuO/ZnO/Al2O3/ZrO2 mixed oxide catalysts. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2002, 4, 1990-9.

Cite This Article

How to Cite

Download Citation

Export Citation File:

Type of Import

Tips on Downloading Citation

Citation Manager File Format

Type of Import

Direct Import: When the Direct Import option is selected (the default state), a dialogue box will give you the option to Save or Open the downloaded citation data. Choosing Open will either launch your citation manager or give you a choice of applications with which to use the metadata. The Save option saves the file locally for later use.

Indirect Import: When the Indirect Import option is selected, the metadata is displayed and may be copied and pasted as needed.

About This Article

Copyright

Data & Comments

Data

Comments

Comments must be written in English. Spam, offensive content, impersonation, and private information will not be permitted. If any comment is reported and identified as inappropriate content by OAE staff, the comment will be removed without notice. If you have any queries or need any help, please contact us at support@oaepublish.com.