Research progress on cognitive frailty in elderly patients with prostate cancer

Abstract

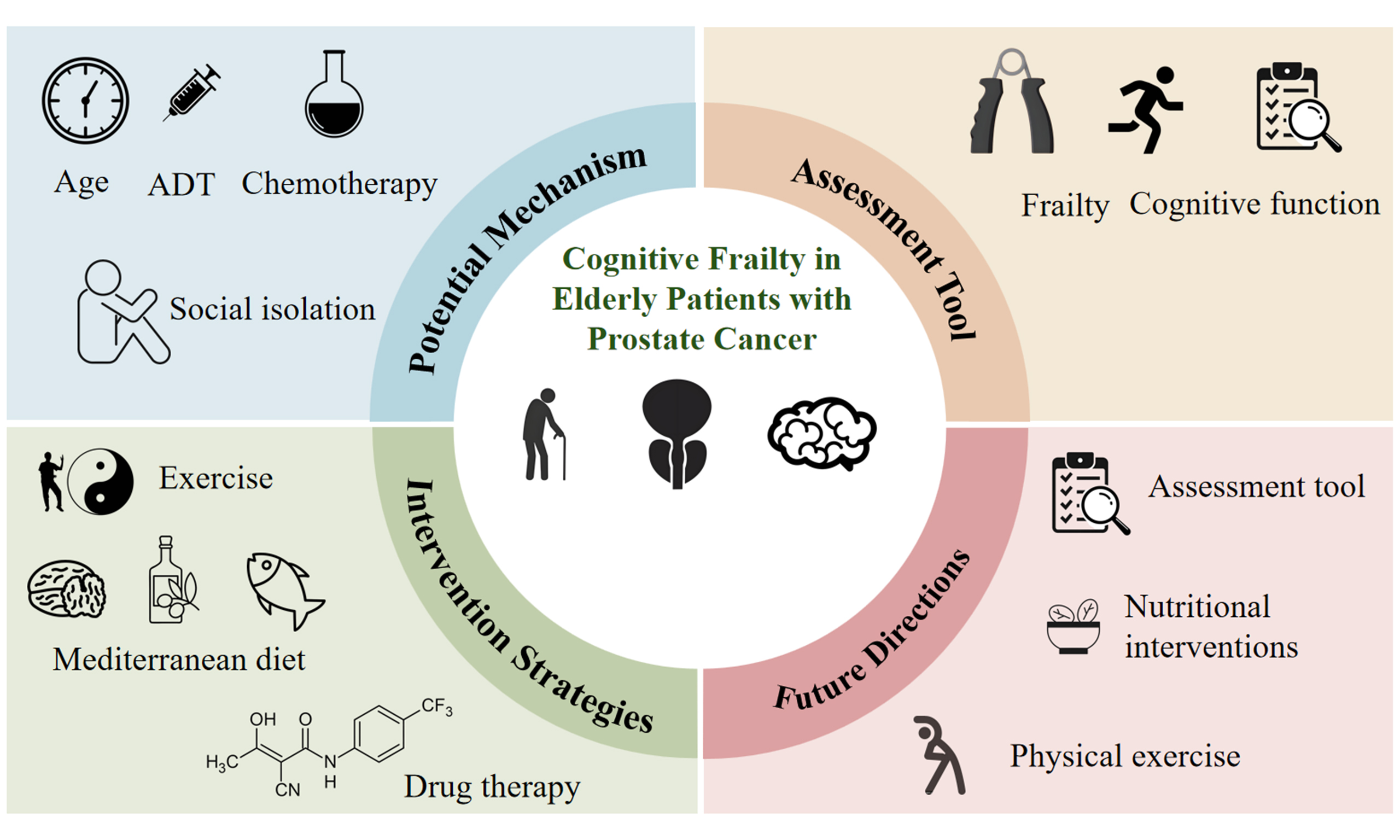

Against the backdrop of global population aging, prostate cancer (PCa), as one of the most common malignant tumors in elderly men, has an association with cognitive frailty (CF) that has garnered increasing attention. CF significantly elevates the risk of adverse health outcomes such as dementia, falls, disability, and mortality in elderly PCa patients. This review systematically summarizes the existing evidence regarding assessment tools, underlying mechanisms, and intervention strategies for CF in elderly PCa patients. Currently, there is no gold standard for PCa-specific CF assessment. The pathogenesis of CF involves complex interactions among multiple pathways: age-related physiological decline, chronic systemic inflammation induced by PCa and its treatments, neuroendocrine dysregulation, oxidative stress, blood-brain barrier impairment, and psychosocial factors. Interventions for CF encompass non-pharmacological strategies and emerging pharmacological treatments. However, these approaches face challenges, including undefined optimal protocols, poor long-term adherence, and insufficient clinical validation. Future research should focus on: developing and validating integrated CF assessment tools tailored for PCa patients; elucidating the molecular mechanisms of CF in the context of PCa; designing and validating personalized, multimodal intervention regimens; bridging the digital divide to advance clinical translation of digital health technologies; rigorously evaluating the benefit-risk profiles of pharmacological interventions through large-scale, long-term clinical trials. Addressing CF in elderly PCa patients is crucial for optimizing disease management, improving quality of life, and guiding targeted clinical interventions.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

The global aging population is facing an increasing array of health challenges, which have become a major focus of medical research. Prostate cancer (PCa), one of the most prevalent cancers in men, is particularly prominent in the elderly male demographic. Epidemiological data indicate that PCa accounts for 13.5% of all cancers and ranks among the most common malignancies in men worldwide. It is also the second leading cause of cancer-related deaths in men, after lung cancer[1]. According to a 2020 report, approximately 1.4 million new cases of PCa are diagnosed annually, resulting in approximately 375,000 deaths[2]. Research suggests that PCa predominantly affects older men, with the risk of onset significantly increasing after the age of 50. At the time of diagnosis, patients are typically older, with a median age of 67[3]. Consequently, research targeting this high-risk cohort is of substantial importance.

Frailty is a clinical syndrome strongly associated with aging, resulting from the accumulation of declines in multiple physiological systems, leading to decreased physiological reserves and reduced resistance to stressors[4]. Mild cognitive impairment (MCI) is an early stage of dementia, serving as a transitional phase between normal aging and dementia, with the potential to progress to various forms of dementia[5]. Cognitive frailty (CF) is defined as the coexistence of physical frailty and MCI, whose interaction contributes to an accelerated decline in functional capacity. Studies indicate that CF increases the risk of dementia, falls, disability, reduced quality of life, and mortality in the elderly[3]. Compared to physical frailty or cognitive impairment alone, CF serves as a stronger predictor of adverse health outcomes.

In PCa, the biological characteristics of the disease, together with the heterogeneity of treatment modalities (including surgery, radiotherapy, chemotherapy, and hormone therapy), particularly the widespread application of androgen deprivation therapy (ADT), are associated with a substantially higher incidence of CF compared with that observed in the general elderly population. This elevated risk subsequently influences patients’ treatment responses, quality of life, and functional independence. Despite the clinical importance of this issue, research on CF among elderly patients with PCa remains limited. Addressing CF in this population not only facilitates the optimization of disease management strategies but also provides a theoretical foundation for the development of targeted clinical interventions. Accordingly, this review aims to systematically synthesize the current evidence in this field, with the goal of informing clinical practice and guiding future research on elderly patients with PCa.

ASSESSMENT TOOLS OF CF

Currently, there is no standardized assessment tool for diagnosing CF in elderly patients with PCa. Existing research primarily evaluates CF from two perspectives: physical frailty and cognitive function. Common tools used to assess physical frailty include the Fried frailty phenotype scale, the G8 screening scale, the Fatigue, Resistance, Ambulation, Illnesses, and Loss of Weight (FRAIL) scale, and the Vulnerable Elders Survey-13 (VES-13) scale. Cognitive function is typically evaluated using the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE), the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA), and the Mini-Cog scale. A systematic comparison of assessment tools for frailty and cognitive function is presented in Table 1.

Systematic comparison of frailty tools and cognitive tools

| Tool | Advantages | Limitations | Applicability to elderly PCa patients | Tumor validation status |

| Fried FP Scale | Gold standard for physical frailty assessment; strong predictive ability for outcomes such as mortality and disability; widely used in PCa research | Requires specialized equipment (e.g., dynamometer); time-consuming (15-20 min); does not account for tumor-specific factors (e.g., chemotherapy effects); limited validation in cancer populations | Suitable for research environments, predicts surgical risks; limited for large-scale clinical use due to time and equipment requirements | Limited in advanced cancer |

| G8 Screening Tool | High sensitivity and specificity; simple and quick to administer; shows strong association with quality of life in PCa research | Inadequate for evaluating complex health conditions (e.g., multimorbidity); lack of systematic validation in cancer populations | Ideal for initial screening, especially for quick outpatient assessments; validated for differences in localized and metastatic PCa patients | Stage-specific validation |

| FRAIL Scale | Concise and efficient (< 5 min); suitable for large-scale screening; associated with depression and sleep quality in PCa research | Lacks depth of evaluation, needs to be combined with other tools; not optimized for tumor-related frailty | Valuable for preoperative assessments; weaker applicability for cognitive components; recommended for risk stratification | Limited in metastatic PCa |

| VES-13 | High reliability and ease of use; performs well in advanced PCa patients; easy to understand and score | Focuses on overall frailty rather than specific cognitive frailty; limited tumor validation for specific subtypes | Suitable for advanced or frail PCa patients; highly operational in clinical settings but requires cognitive assessment supplementation | Needs early-stage data |

| MMSE | Widely used and simple; quick to score; low cost | Low sensitivity in elderly with high education; cannot detect mild cognitive changes; sparse tumor population validation | Feasible as a baseline screening tool, but may miss PCa-related cognitive impairments; not recommended as a standalone tool | No (validated in dementia) |

| MoCA | Highly accurate for mild cognitive impairment (MCI); more sensitive than MMSE; covers multiple cognitive domains | Longer test time (10-15 min); not specifically validated in oncology; influenced by cultural factors | Recommended for detailed cognitive assessments; better captures chemotherapy-related changes; requires more PCa research support | Not in geriatric oncology (although use considered feasible); Has been used in older adults with cancer |

| Mini-Cog | Very brief (around 3 min); less affected by language/education; recommended by SIOG for elderly cancer patients | May not detect specific deficits such as executive function; incomplete validation in diverse cancer populations | Best initial screening tool for elderly PCa patients; validated in some studies; suitable for busy clinical environments | No (validated in dementia) |

Frailty assessment

The Fried Frailty Phenotype Scale

The Fried Frailty Phenotype (FP) Scale was initially proposed by Fried et al. in 2001[4]. Due to its high validity in assessment, it is internationally recognized as the gold standard for evaluating physical frailty and has been extensively applied worldwide. The scale includes five indicators: unintentional weight loss, fatigue, low physical activity, slow gait, and weak grip strength. Individuals who meet 1-2 criteria are classified as pre-frail, while those who meet 3 or more criteria are diagnosed as frail. This scale is commonly used to evaluate physical frailty in elderly populations and demonstrates strong predictive capacity, particularly in forecasting outcomes such as mortality, disability, falls, hospitalization, and surgical risk in older adults. The FP scale is currently the most frequently employed tool for assessing frailty in PCa patients[6]. However, the implementation of the FP scale presents certain limitations: it requires specialized tools such as a grip dynamometer and a timer for standardized measurements, and a complete assessment typically takes 15-20 min. These factors may pose challenges for large-scale clinical application. Additionally, the FP scale primarily evaluates physical frailty based on signs and symptoms associated with energy decline, without considering specific comorbidities or psychosocial factors.

The G8 Screening Tool

The G8 Screening Tool was developed by Bellera et al. in 2012[7]. Its assessment framework integrates seven components from the Mini Nutritional Assessment scale (including appetite loss, weight loss, reduced activity, psychological issues, body mass index, number of medications, and self-rated health) along with age-related factors. The scoring range is from 0 to 17 points, with a score of ≤ 14 indicating frailty. This tool demonstrates good sensitivity, specificity, and applicability, facilitating rapid frailty assessment in elderly patients. Due to its simplicity and efficiency, it has become a commonly used initial screening tool in comprehensive geriatric assessments. A study by Hamaya et al., which employed the G8 Screening Tool to evaluate frailty in 409 patients with PCa, demonstrated significant differences in baseline frailty scores between those with localized and metastatic disease (14.5 vs. 12.5)[8]. Furthermore, baseline frailty was significantly associated with poorer health-related quality of life among patients with PCa.

The FRAIL Scale

The FRAIL Scale, proposed by the International Association of Nutrition and Aging (IANA) in 2008, evaluates five components: fatigue, gait, endurance, weight loss, and physical activity. The total score ranges from 0 to 5, with a score of 0 indicating no frailty, 1-2 indicating pre-frailty, and 3-5 indicating frailty. The FRAIL scale is straightforward and time-efficient, making it suitable for large-scale screening. However, its evaluation of complex health conditions lacks comprehensiveness, necessitating its combination with other assessment methods. Liang et al. employed the FRAIL scale to assess 277 elderly PCa patients undergoing radical prostatectomy. The results demonstrated that elderly PCa patients who underwent surgery had a higher risk of depression[9]. Frailty, acting as a dual-pathway predictor, not only directly exacerbated depressive symptoms in PCa patients but also indirectly influenced depression through a decline in sleep quality.

The Vulnerable Elders Survey-13

The VES-13, developed by Saliba et al. in 2001, is a widely used frailty assessment tool. It includes four dimensions: age, self-rated health, physical function, and activities of daily living, with a total of 13 items. A higher score signifies greater frailty and an increased risk of injury[10]. Feng et al. utilized the VES-13 scale to assess frailty in 150 elderly patients with advanced castration-resistant PCa[11]. The scale is characterized by high reliability and operability, ease of understanding and use, making it an effective tool for assessing frailty in advanced PCa patients.

Cognitive function assessment

The Mini-Mental State Examination

The MMSE, developed by Folstein et al. in 1975, is a widely used and simple cognitive assessment tool[12]. It evaluates six dimensions of cognitive function: orientation, memory, attention, calculation, recall, and language ability. The total score ranges from 0 to 30, with a score of < 27 indicating cognitive impairment. However, the MMSE has certain limitations in detecting cognitive impairment in specific patient subgroups, particularly in elderly individuals with higher levels of education[13].

The Montreal Cognitive Assessment

The MoCA, developed by Nasreddine et al. in 2005, is a highly accurate tool for screening MCI[14]. The assessment includes eight domains: visuospatial and executive functions, naming, memory, attention, language, abstraction, delayed recall, and orientation, with a total score of 30 points. A score of < 21 points is indicative of cognitive impairment. Compared to the MMSE, the MoCA offers superior sensitivity and rigor in detecting cognitive deficits[13].

The Mini-Cog scale

The Mini-Cog scale, introduced by Borson et al. in 2000, comprises a clock drawing test (CDT) and a delayed recall task[15]. It demonstrates high sensitivity across diverse age groups. A score of 3 signifies the ability to recall all three words, suggesting the absence of cognitive impairment. A score of 1-2 indicates recall of only one or two words, with further evaluation based on the CDT result. A completely accurate CDT suggests normal cognitive function, while an incorrect CDT indicates cognitive dysfunction. A score of 0 denotes failure to recall any of the three words, which is typically indicative of dementia. This scale is brief to administer (approximately 3 min), minimally affected by language and education level, and is recommended by the International Society of Geriatric Oncology (SIOG) as a primary screening tool for assessing cognitive health in elderly PCa patients[16].

POTENTIAL MECHANISM

Currently, research on the relationship between PCa and CF is limited. Most studies focus on the relationship between PCa and frailty, as well as PCa and cognitive dysfunction.

Age and physiological decline

Age is a significant risk factor for both PCa and CF. More than 75% of PCa patients are over 65 years of age at the time of diagnosis. As individuals age, males experience degenerative changes in multiple systems, including gonadal dysfunction, reduced testosterone levels, and a loss of muscle mass. These physiological changes result in a decline in physiological reserve, making older individuals more susceptible to physical frailty[17]. Moreover, the decrease in testosterone levels not only affects male physiological functions but may also negatively influence brain function. Studies have shown that testosterone plays an important neuroprotective role in the brain, enhancing neuroplasticity and improving cognitive function. As testosterone levels decline, male cognitive performance may deteriorate, exacerbating CF symptoms. In PCa patients, aging further amplifies the dual risks of frailty and cognitive decline. Existing research on CF in PCa patients has notable limitations, such as the lack of age stratification, inadequate control of comorbidities, and treatment heterogeneity. Future studies should employ rigorous designs to isolate confounding factors[18].

Chronic systemic inflammation

PCa cells and the tumor microenvironment activate the NLRP3 (nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain (NOD)-, leucine-rich repeat (LRR)- and pyrin domain-containing protein 3) inflammasome, triggering caspase-1-dependent maturation and release of interleukin (IL)-1β/IL-18, promoting tumor progression[19,20]. In systemic inflammation of PCa, IL-1β driven by the NLRP3 inflammasome crosses the blood-brain barrier, activating the microglial Toll-like receptor (TLR4)/nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) pathway. This inflammatory signal activates NF-κB via TLR4, leading to the release of neurotoxic factors and impairing neuronal synaptic plasticity. ADT therapy and chemotherapy drugs [such as docetaxel (DOC)] can further activate the NLRP3 inflammasome, forming a malignant cycle. However, the specific molecular mechanisms and biological functions of the NLRP3 inflammasome in PCa remain to be fully elucidated. Moreover, the differential effects of various therapeutic strategies on inflammasome activation warrant validation through further clinical cohort studies[21].

Androgen deprivation therapy

As a cornerstone treatment for PCa, approximately 50% of PCa patients undergo ADT following diagnosis. However, ADT reduces testosterone levels, leading to a series of physiological and psychological effects. By maintaining testosterone at castrate levels, ADT may cause sarcopenia, decreased bone mineral density, increased risk of falls, and exacerbated fatigue, all of which contribute to the worsening of the patient’s frailty[17]. In recent years, the impact of ADT on cognitive function has become a research focus. Nevertheless, there is currently no consensus on the cognitive impairments induced by hormone therapy in PCa. A systematic literature review on the cognitive effects of ADT highlighted that the heterogeneity in the definitions and measurement tools used has led to considerable variability in the reported incidence and severity of cognitive impairments across studies[18]. Furthermore, differences in patient populations, such as age range, education level, comorbidities, and the choice of ADT regimen, may influence the tendency for cognitive decline in patients undergoing ADT[13,17]. The specific mechanisms by which ADT affects cognitive function in patients remain to be fully elucidated. Potential mechanisms include the following:

Neuroendocrine and metabolic disorders

ADT is a cornerstone of PCa treatment, but it leads to a sharp decline in serum testosterone levels. The androgen receptor (AR) is expressed in various brain regions, including the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex, where it plays a role in regulating synaptic plasticity, neurogenesis, and neuroprotection. Inhibition of AR signaling directly affects the expression of genes related to neuronal function and survival, such as brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF). ADT may also downregulate the expression of key neurotrophic factors such as BDNF and insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1), impairing the maintenance and repair capacity of neurons[22]. Both cancer and ADT can lead to excessive activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, resulting in persistently elevated cortisol levels. High cortisol levels exert direct toxic effects on hippocampal neurons, damaging synaptic plasticity and exacerbating neuroinflammation[23]. A study by Buskbjerg et al., involving cognitive assessments, structural magnetic resonance imaging, and blood samples before and six months after ADT treatment in 37 PCa patients, reported that 27 age- and education-matched healthy controls received the same assessments[24]. The findings indicated that PCa patients undergoing ADT might experience cognitive decline. However, no changes were observed in brain connectivity or in the role of testosterone levels as potential mechanisms. Future studies need to further assess the role of the dynamic imbalance of the HPA axis related to ADT[24]. A deeper understanding of these mechanisms is of great significance for the future development of new targets and strategies for the prevention and treatment of CF in elderly PCa patients.

Oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction

Androgen deficiency reduces the activity of mitochondrial antioxidants, such as superoxide dismutase (SOD) and glutathione peroxidase (GPX), leading to the accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS). This causes oxidative stress, resulting in neuronal DNA damage and accelerating cell aging and death. The downregulation of antioxidant genes such as superoxide dismutase 2 (SOD2) and glutathione peroxidase 1 (GPX1) further accelerates neuronal apoptosis. Excessive ROS attacks the mitochondria, causing mitochondrial DNA damage, a decrease in membrane potential, and reduced adenosine triphosphate (ATP) synthesis. Neurons are highly dependent on mitochondrial energy supply, and mitochondrial dysfunction directly affects synaptic transmission, neurotransmitter synthesis, and neuronal survival[25]. Based on this mechanism, preclinical studies and clinical trials have reported the beneficial effects of antioxidant-rich diets in reducing PCa risk. However, not all studies support a clear association between these dietary patterns and the risk of PCa[26]. Therefore, future studies are needed to assess the molecular links, to better elucidate the potential role of these dietary patterns in the prevention and treatment of PCa.

Blood-brain barrier damage

Studies have shown that the low-testosterone state induced by ADT, along with potential hypogonadism, can activate the monocyte/macrophage system, leading to increased circulating pro-inflammatory factors such as IL-6 and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α). These inflammatory factors and ROS may disrupt the tight junction proteins between endothelial cells in the blood-brain barrier (BBB), including occludin, claudin-5, and Zonula Occludens-1 (ZO-1), resulting in a reduction in their expression and an increase in BBB permeability. PCa cells can secrete matrix metalloproteinases (MMP-2, MMP-9), which further degrade components of the basement membrane[27]. Research in mice indicates that ADT may compromise the integrity of the BBB, facilitating immune cell infiltration into the brain, thereby exacerbating neuroinflammation and glial cell proliferation, impairing neuronal function, and synaptic plasticity, which negatively impacts brain function. The AR inhibitor darolutamide has shown significantly lower BBB permeability in male mouse models compared to AR inhibitors enzalutamide and apalutamide, which is consistent with its lower risk of CNS-related (CNS = Central Nervous System) adverse events in clinical settings[28]. However, these conclusions are based on animal models, and directly proving that BBB damage is a key driver of cognitive dysfunction in humans remains a challenge. Further clinical studies are needed to validate this hypothesis.

Sarcopenia

ADT is a major contributing factor to the development of sarcopenia in patients with PCa. Low testosterone levels directly inhibit muscle protein synthesis while promoting catabolism, leading to a rapid decline in skeletal muscle mass and strength. Sarcopenia results in reduced secretion of beneficial myokines, such as Irisin, and an increase in pro-inflammatory myokines, including myostatin and IL-6. These dysregulated myokines may affect the brain via the circulatory system, inhibiting the production of neurotrophic factors, exacerbating neuroinflammation, and elevating oxidative stress[29]. Sarcopenia significantly reduces physical activity, further decreasing cerebral blood flow and neurotrophic factor levels, creating a vicious cycle. A meta-analysis showed that ADT significantly alters body composition: the reduction in skeletal muscle density (SMD) has a strong effect [95% confidence interval (CI): -0.69 to -0.24], the reduction in skeletal muscle index (SMI) has a moderate effect (95%CI: -0.57 to -0.19), and the subcutaneous adipose tissue index (SATI) significantly increases (95%CI: 0.13-0.51), contributing to the development of sarcopenia[30]. However, the precise mechanisms by which ADT affects muscle health remain unclear and require further investigation.

Chemotherapy-related neurotoxicity

When PCa becomes resistant to ADT, chemotherapy is commonly employed for the management of advanced or metastatic PCa. Chemotherapy drugs such as DOC primarily induce DNA damage and promote apoptosis to disrupt cancer cell division. These therapies significantly elevate the production of ROS, including hydroxyl radicals (OH-), superoxide anions (O2-), and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2). ROS can cause damage to lipids, proteins, and DNA in neurons. Concurrently, the antioxidant defense system, which includes glutathione (GSH), catalase, and SOD, becomes impaired, exacerbating neuronal damage[25] and potentially compromising cognitive function. Additionally, chemotherapy-induced side effects, including fatigue, sleep disturbances, and malnutrition, further exacerbate physical frailty[31]. Studies have shown that frailty significantly affects chemotherapy treatment in PCa, often resulting in the premature discontinuation of DOC, a first-line chemotherapy agent for metastatic PCa, after fewer than three cycles[32]. Therefore, identifying frail patients and carefully selecting appropriate medications and dosages is essential for minimizing treatment toxicity, enhancing treatment tolerance, and ensuring patient safety. However, a study by Alibhai et al. reported that most elderly men undergoing chemotherapy for advanced PCa did not exhibit significant cognitive decline in attention, executive function, or overall cognition[33]. Future research is required to further explore the specific effects of chemotherapy on cognitive function in PCa patients[33].

Social psychological factors

In addition to biological and treatment factors, social psychological factors play an important role in CF in elderly PCa patients. Studies have shown that chemotherapy and ADT can lead to alterations in body image, a loss of masculinity due to sexual dysfunction, and low self-esteem accompanied by stigma[34]. Several review studies have indicated that ADT increases the risk of depression, which, in turn, exacerbates the impact of ADT-related side effects on PCa identity and psychological distress[35]. The risk of depression in PCa patients undergoing ADT is 41% higher than that in the general population, while the risk of dementia is 47% higher[36]. The mechanism by which anxiety triggers CF in PCa patients may involve anxiety-induced dysregulation of histone deacetylase (HDAC) expression, particularly enhanced activity, which leads to impairments in acetylation and deacetylation processes, thereby suppressing neuroprotective genes such as SIRT1 (SIRT1 = sirtuin1)[37]. Based on this mechanism, antidepressants are currently being investigated as potential interventions for cognitive improvement in PCa patients. However, research on the relationship between psychosocial factors, frailty, and cognitive function in PCa patients undergoing ADT remains limited and is still in early stages. Further research is required to validate the effects of psychosocial factors on cognitive function in ADT-treated PCa patients[38]. Future studies should delve deeper into the impact of psychosocial factors on CF in PCa patients and explore effective interventions to improve patients’ social support systems and mental health.

INTERVENTION

Cognitive intervention

Lifestyle intervention is a crucial component of managing CF. Zhang et al. proposed that combining patient and family education with psychological counseling can effectively promote self-management and enhance coping strategies. Expanding the social support network is vital for assisting patients to manage both basic and instrumental daily activities (such as financial management and medication management), thereby enhancing their ability to live independently. In addition, lifestyle interventions encompass cognitive training and goal-oriented compensatory approaches, including the use of memory aids, structured daily goal setting, and regular medical evaluations[27]. These interventions have been empirically shown to delay cognitive decline effectively[27]. In recent years, the proliferation of digital health technologies in geriatric care - particularly remote monitoring systems, wearable sensors, and intelligent health platforms - has provided effective tools for the continuous tracking of patients’ physiological and cognitive status. Combined with artificial intelligence-driven data analysis, they can assist healthcare professionals in early identification of CF signs and timely intervention to mitigate disease progression. Several meta-analyses have highlighted the potential of digital health technologies in remote monitoring of CF in PCa patients, especially in the areas of lifestyle management, symptom self-management, and treatment side effects[39-41]. However, existing studies remain predominantly in their preliminary stages, characterized by small sample sizes, short intervention durations, and insufficient long-term outcome data or rigorous efficacy validation for elderly PCa patients with CF, which limits the generalizability of the research. Despite the promising outlook, the widespread application of digital health technologies for managing CF in elderly PCa patients encounters significant challenges[42]: (1) Digital divide: Many elderly patients may lack the necessary digital literacy, access to devices, or stable internet connectivity, which constrains technological accessibility and patient compliance[43]; (2) Multimorbidity and cognitive impairment: The coexistence of multiple chronic conditions and cognitive decline may hinder patients’ ability to effectively navigate or comprehend these technological interfaces, while comorbidities further restrict their active participation; (3) Data security and privacy: Elderly patients often express concerns regarding privacy and data protection within remote healthcare systems; (4) Cost-effectiveness: The development, implementation, and maintenance expenses of these technologies - as well as their comparative cost-effectiveness relative to conventional care models - require further systematic evaluation. Therefore, achieving the clinical translation of digital health technologies for managing CF in elderly PCa patients not only requires continuous technological optimization but also addressing the aforementioned evidence gaps and implementation barriers. This process entails the design of targeted randomized controlled trials (RCTs), development of user-friendly geriatric interfaces, reinforcement of data security frameworks, provision of comprehensive training programs, and rigorous cost-effectiveness evaluations.

Exercise intervention

Exercise intervention plays a pivotal role in the non-pharmacological management of CF in older adults. A comprehensive review revealed that exercise interventions have positive effects on frailty, cognitive function, nutritional status, and depressive symptoms in older adults with CF[44]. Existing evidence[45], derived from a systematic review of 18 RCTs, supports the use of exercise as a non-pharmacological intervention to enhance disease-specific quality of life, walking ability, and frailty status in PCa patients receiving ADT. Specifically, a meta-analysis by Kempin showed significant effects from interventions combining strength training and aerobic exercise[46]. A meta-analysis by Fang et al., which included 10 RCTs, indicated that exercise interventions during and after cancer treatment led to small to moderate improvements in self-reported cognitive function in PCa patients, with an effect size ranging from 0.12 to 0.58[47]. However, these exercise intervention trials have several limitations and face unique challenges when applied to elderly PCa patients: (1) Uncertainty about the optimal exercise regimen: There is currently a lack of RCTs comparing the effects of aerobic exercise and resistance training in PCa patients with CF; (2) Challenges with long-term adherence: The side effects of ADT and CF itself may reduce adherence to exercise prescriptions in elderly PCa patients, such as forgetting to exercise, difficulty following complex instructions, or lack of motivation. A meta-analysis showed that adherence to home-based exercises is the lowest, at just 49%[48]. Exercise instructions should be simplified, and additional reminders and supervision support should be provided; (3) Safety monitoring: Common issues such as multimorbidity, ADT-related fatigue, sarcopenia, and reduced physical reserve may significantly limit the ability of elderly PCa patients to tolerate moderate to high-intensity exercise, thus increasing the risk of injury. Some studies did not report adverse events, while those that did report adverse events indicated that PCa patients experienced musculoskeletal injuries, pain, fractures, and non-fatal myocardial infarctions after exercise[47,48]. The statistical power of the existing trials is inadequate to assess the impact of exercise interventions on adverse events, and larger sample sizes, as well as longer follow-up periods, may be required to verify the impact of exercise therapy on safety. Future exercise prescriptions must be highly individualized, taking into account the effects of these comorbidities. Elderly frail patients require more intensive monitoring during exercise to prevent adverse events, posing greater challenges for exercise interventions in home or community settings. Therefore, although exercise therapy holds significant promise, high-quality clinical evidence on its effectiveness in managing CF in elderly, comorbid PCa patients is still limited. Future research urgently needs to confirm the benefit-risk ratio through large-scale, long-term RCTs in this population. Before widespread implementation, key barriers such as patient factors (e.g., digital literacy, comorbidities), technology integration, and healthcare system adaptability must be overcome. Future research should focus on: identifying individualized, safe, and effective exercise prescriptions for different degrees of CF and comorbidity profiles (considering comorbidities, functional limitations, treatment side effects, and patient preferences); developing strategies to improve adherence; and evaluating feasible and effective models for implementation in resource-limited settings (e.g., home-based exercise, remote guidance).

Nutritional support

Malnutrition represents a significant risk factor for the development of CF. Nutritional interventions play a key role in improving both cognitive function and frailty status in elderly individuals. A systematic review encompassing 19 RCTs has demonstrated that nutritional support is the most effective non-pharmacological intervention for improving both physical frailty and cognitive decline in CF patients[49]. The Mediterranean diet (MD), rich in monounsaturated fatty acids, polyunsaturated fatty acids, and DHA (DHA = docosahexaenoic acid), has been shown to have a positive effect on both physical and cognitive functions. A RCT involving 23 men with PCa undergoing ADT revealed that a 12-week MD regimen could alleviate cancer-related fatigue and improve quality of life[50]. However, there is currently a lack of RCTs specifically focused on CF in the context of PCa. While multifactorial lifestyle interventions have shown positive effects on weight, body composition, and quality of life, the effects of dietary interventions in isolation remain challenging to quantify[51,52]. Furthermore, medium-quality evidence from Inglis et al. (RCT, n = 59) reported that a 24-week high-dose vitamin D (50,000 IU/week + 600 IU/day) intervention significantly reduced frailty compared to the control group (placebo/week+600 IU/day)[6]. Additionally, elderly PCa patients face numerous challenges in implementing nutritional interventions, including treatment-related anorexia, swallowing difficulties, socioeconomic barriers to food access, and the difficulty of maintaining dietary adjustments due to cognitive decline. Elderly patients frequently suffer from comorbid conditions and are prescribed multiple medications, necessitating that dietary plans account for these factors and be coordinated with pharmacological treatments. Moreover, their ability to chew, swallow, and digest food may decline, requiring adjustments to the texture of food. Consequently, conducting research to determine the most effective nutritional interventions for men undergoing ADT is of critical importance.

Pharmacological treatment

Preclinical studies suggest that antidepressants such as Vortioxetine may reverse hippocampal alterations and visuospatial cognitive deficits by restoring the neuroplasticity mechanisms disrupted by ADT at both molecular and neural circuit levels. In animal models, this has shown potential in alleviating ADT-related cognitive decline[53]. However, Vortioxetine remains in the preliminary phase of investigation as a treatment for ADT-related CF. Therefore, there is an urgent need to design RCTs specifically for elderly PCa patients to evaluate its clinical efficacy, safety, tolerability, and applicability within the context of multiple comorbidities and polypharmacy. The protective mechanism of mefenamic acid showed insufficient statistical power in a 6-month RCT (N = 28) and lacked long-term safety data, with the long-term use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) potentially increasing gastrointestinal risks[54]. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved natalizumab (NAT), which reduces immune cell infiltration into the brain by inhibiting the adhesion of immune cells to endothelial cells, has shown effects in reducing neuroinflammation in murine models. However, the current evidence primarily derives from preclinical studies, necessitating further clinical validation[27]. The evidence base for pharmacological interventions targeting ADT-related CF remains limited, with notable limitations, including (1) polypharmacy risks: elderly PCa patients often require the concurrent use of multiple medications, which may increase the risk of drug interactions and adverse effects, thus necessitating a careful balance between therapeutic benefits and medication burden; (2) Body tolerance: elderly patients may be more sensitive to drug side effects, potentially exacerbating their frailty or increasing fall risk, highlighting the challenge of balancing tolerance and efficacy; (3) Cognitive impairment: CF may affect patients’ medication adherence and their ability to manage complex drug regimens. Pharmacological treatment of CF in elderly PCa patients remains an exploratory research area. Current clinical evidence suggests that its potential may outweigh the empirical benefits, underscoring the need for large-scale, long-term RCTs targeting this patient population.

FUTURE RESEARCH DIRECTIONS

This review summarizes the latest research on the assessment tools, mechanisms, and intervention strategies for CF in elderly PCa patients. With population aging, their management faces increasingly complex challenges. Studies have shown that the biological characteristics of PCa, treatment regimens (such as ADT and chemotherapy), along with frailty and cognitive dysfunction, are interconnected and significantly heighten the risk of CF in elderly PCa patients. Currently, the absence of a standardized CF assessment tool limits the comparability of research findings. Establishing a unified assessment system would enhance diagnostic accuracy and ensure consistent outcomes. Furthermore, the mechanistic studies of CF remain in the early stages, particularly within the PCa patient population, with specific mechanisms, including physiological decline, chronic inflammation, and ADT therapy, warranting further exploration. While intervention strategies for CF have made progress, particularly in non-pharmacological approaches such as lifestyle changes, exercise, and nutritional support, their application in elderly PCa patients still faces numerous challenges. Regarding pharmacological interventions, although certain antidepressants and neuroprotective agents have shown promise in preventing or alleviating CF, clinical studies remain limited, and larger sample sizes and longer follow-up periods in RCTs are necessary to verify their efficacy and safety.

Future Research Directions: (1) Optimization of Assessment Tools: Future studies should prioritize the development of specialized assessment tools for CF in elderly PCa patients. These tools should integrate frailty, cognitive function, and psychological factors, enabling a more comprehensive evaluation. Furthermore, to effectively incorporate CF screening tools into routine oncological care, these tools must be simple, highly sensitive, and practical for everyday clinical use; (2) In-depth Exploration of Mechanisms: Current research on the mechanisms of CF remains unclear, especially regarding the specific mechanisms in PCa patients. Future studies should explore how factors such as chronic inflammation, ADT, and oxidative stress influence the development of CF through molecular pathways, particularly the profound impacts on the nervous system; (3) Personalized Intervention Strategies: The management of CF in elderly PCa patients should account for individual differences, including age, comorbidities, and lifestyle factors. Future studies should emphasize the development of personalized intervention strategies, incorporating exercise, nutrition, and psychological support. This should focus on assessing the effectiveness of different interventions for patients with varying levels of CF; (4) Application of Digital Health Technologies: The potential of digital health technologies in CF management is substantial, although significant challenges persist. Future studies should aim to enhance digital literacy among elderly PCa patients and develop age-appropriate, user-friendly digital health platforms. Moreover, studies should evaluate the long-term effects and cost-effectiveness of these technologies in managing CF, to facilitate their broader clinical application; (5) Clinical Validation of Pharmacological Interventions: Although pharmacological interventions show potential in improving CF, existing evidence is insufficient. Future research should design large-scale, long-term RCTs to validate the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of pharmacological interventions in elderly PCa patients, particularly those with comorbidities and polypharmacy, while balancing the benefits and adverse effects of these medications.

CONCLUSION

The management of CF in elderly PCa patients remains a complex and evolving challenge that requires ongoing multidisciplinary collaboration and long-term clinical validation. By enhancing assessment tools, deeply exploring underlying mechanisms, implementing personalized interventions, and leveraging digital health technologies, it is anticipated that more effective management strategies will be developed for elderly PCa patients in the future, thereby improving their quality of life and delaying disease progression.

DECLARATIONS

Authors’ contributions

Writing and drafting: Jiang Y, Lu J

Editing: Li J

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Financial support and sponsorship

None.

Conflicts of interest

All authors declared that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2025.

REFERENCES

1. Almeeri MNE, Awies M, Constantinou C. Prostate cancer, pathophysiology and recent developments in management: a narrative review. Curr Oncol Rep. 2024;26:1511-9.

2. Zhang H, Qi L, Cai Y, Gao X. Gastrin-releasing peptide receptor (GRPR) as a novel biomarker and therapeutic target in prostate cancer. Ann Med. 2024;56:2320301.

3. Zhang XM, Wu XJ, Cao J, Jiao J, Chen W. Association between cognitive frailty and adverse outcomes among older adults: a meta-analysis. J Nutr Health Aging. 2022;26:817-25.

4. Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, et al.; Cardiovascular Health Study Collaborative Research Group. Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56:M146-56.

6. Park J, Ryu GW, Lee H, Choi YD, Kim Y. Frailty of prostate cancer patients receiving androgen deprivation therapy: a scoping review. World J Mens Health. 2024;42:347-62.

7. Bellera CA, Rainfray M, Mathoulin-Pélissier S, et al. Screening older cancer patients: first evaluation of the G-8 geriatric screening tool. Ann Oncol. 2012;23:2166-72.

8. Hamaya T, Hatakeyama S, Momota M, et al. Association between the baseline frailty and quality of life in patients with prostate cancer (FRAQ-PC study). Int J Clin Oncol. 2021;26:199-206.

9. Liang W, Chen X, Zeng C, Zhang H, Qin H, Jiang M. The relationship between frailty and depression in Chinese elderly prostate cancer patients following radical surgery: the mediating effect of sleep disturbances. Support Care Cancer. 2025;33:315.

10. Saliba D, Elliott M, Rubenstein LZ, et al. The Vulnerable Elders Survey: a tool for identifying vulnerable older people in the community. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001;49:1691-9.

11. Feng J, Sun Q, Li J, Li TT. Reliability and validity test of VES-13 and analysis of influencing factors for the vulnerable condition of patients with advanced castration-resistant prostate cancer. Pak J Med Sci. 2021;37:137-41.

12. Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189-98.

13. Wefel JS, Ryan CJ, Van J, Jackson JC, Morgans AK. Assessment and management of cognitive function in patients with prostate cancer treated with second-generation androgen receptor pathway inhibitors. CNS Drugs. 2022;36:419-49.

14. Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bédirian V, et al. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:695-9.

15. Borson S, Scanlan J, Brush M, Vitaliano P, Dokmak A. The Mini-Cog: a cognitive ‘vital signs’ measure for dementia screening in multi-lingual elderly. Int J Geriat Psychiatry. 2000;15:1021-7.

16. Droz JP, Albrand G, Gillessen S, et al. Management of prostate cancer in elderly patients: recommendations of a task force of the international society of geriatric oncology. Eur Urol. 2017;72:521-31.

17. Pathak N, Papadopoulos E, Kumar V, Alibhai S. Frailty in older adults with prostate cancer. Eur Urol Oncol. 2025;8:14-20.

18. Boué A, Joly F, Lequesne J, Lange M. Does hormone therapy impact cognition in patients with prostate cancer? Cancer. 2024;130:2120-38.

19. Zhao AN, Yang Z, Wang DD, et al. Disturbing NLRP3 acetylation and inflammasome assembly inhibits androgen receptor-promoted inflammatory responses and prostate cancer progression. FASEB J. 2022;36:e22602.

20. Alsaadi M, Tezcan G, Garanina EE, et al. Doxycycline attenuates cancer cell growth by suppressing NLRP3-mediated inflammation. Pharmaceuticals. 2021;14:852.

21. Xu Z, Wang H, Qin Z, et al. NLRP3 inflammasome promoted the malignant progression of prostate cancer via the activation of caspase-1. Cell Death Discov. 2021;7:399.

22. Ravi P, Wang V, Fichorova RN, et al. IGF-1 axis changes with ADT and docetaxel in metastatic prostate cancer. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2023;30:e230241.

23. Ajdžanović V, Ćosić P, Trifunović S, et al. Structure and hormonal output of the adrenal gland after experimental estrogenization of male rats. Histol Histopathol. 2025;40:1377-96.

24. Buskbjerg CR, Amidi A, Buus S, Gravholt CH, Hadi Hosseini SM, Zachariae R. Androgen deprivation therapy and cognitive decline-associations with brain connectomes, endocrine status, and risk genotypes. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2022;25:208-18.

25. Philips TJ, N’guessan BB, Dotse E, Abankwah JK, Appiah-Opong R. Riboceine and N-acetylcysteine protect normal prostate cells from chemotherapy-induced oxidative stress while selectively modulating the cytotoxicity of methotrexate and docetaxel in prostate (PC-3) and breast cancer (MCF-7) cells. Biomed Pharmacother. 2025;190:118355.

26. Tan BL, Norhaizan ME. Oxidative stress, diet and prostate cancer. World J Mens Health. 2021;39:195-207.

27. Zhang C, Aida M, Saggu S, et al. Androgen deprivation therapy exacerbates Alzheimer’s-associated cognitive decline via increased brain immune cell infiltration. Sci Adv. 2024;10:eadn8709.

28. Williams SCR, Mazibuko N, O’Daly O, et al. Comparison of cerebral blood flow in regions relevant to cognition after enzalutamide, darolutamide, and placebo in healthy volunteers: a randomized crossover trial. Target Oncol. 2023;18:403-13.

29. Arosio B, Calvani R, Ferri E, et al. Sarcopenia and cognitive decline in older adults: targeting the muscle-brain axis. Nutrients. 2023;15:1853.

30. Stelmach-Mardas M, Warchoł W, Garczyk A, et al. Influence of androgen deprivation therapy on the development of sarcopenia in patients with prostate cancer: a systematic review. Nutrients. 2024;16:656.

31. Zheng F, Zhao Y, Ren X, Lan X, Peng W. Prevalence and associated factors of cognitive frailty in older patients with lung cancer undergoing chemotherapy: a cross-sectional study. Support Care Cancer. 2025;33:762.

32. Mafla-España MA, Torregrosa MD, Cauli O. Analysis of frailty syndrome in men with metastatic prostate cancer: a scoping review. J Pers Med. 2023;13:319.

33. Alibhai SMH, Breunis H, Feng G, et al. Association of chemotherapy, enzalutamide, abiraterone, and radium 223 with cognitive function in older men with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4:e2114694.

34. Pan S, Wang L, Zheng L, et al. Effects of stigma, anxiety and depression, and uncertainty in illness on quality of life in patients with prostate cancer: a cross-sectional analysis. BMC Psychol. 2023;11:129.

35. Siebert AL, Lapping-Carr L, Morgans AK. Neuropsychiatric impact of androgen deprivation therapy in patients with prostate cancer: current evidence and recommendations for the clinician. Eur Urol Focus. 2020;6:1170-9.

36. Izard JP, Siemens DR. Androgen deprivation therapy and mental health: impact on depression and cognition. Eur Urol Focus. 2020;6:1162-4.

37. Baek SY, Lee J, Kim T, et al. Development of a novel histone deacetylase inhibitor unveils the role of HDAC11 in alleviating depression by inhibition of microglial activation. Biomed Pharmacother. 2023;166:115312.

38. Pembroke L, Sherman KA, Francis H, Dhillon HM, Gurney H, Gillatt D. Psychosocial factors associated with cognitive function in prostate cancer survivors on hormonal treatments: a systematic review. Neuropsychol Rev. 2025;35:319-36.

39. Chen HS, He H, Lin HH, Zhang Y, Li N, Li YM. Effectiveness of mobile health in symptom management of prostate cancer patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Digit Health. 2025;7:1584764.

40. Raya Benítez J, Valenza Peña G, Martín Núñez J, et al. Effects on quality of life and self-efficacy of instant messaging services in self-management programs for prostate cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancers. 2025;17:465.

41. Gómez-Luque MÁ, Rivero-Belenchón I, Congregado-Ruiz CB, et al. The role of mhealth applications in uro-oncology: a systematic review and future directions. Cancers. 2025;17:2613.

42. Ogunsanya ME, Sifat M, Bamidele OO, et al. Mobile health (mHealth) interventions in prostate cancer survivorship: a scoping review. J Cancer Surviv. 2023;17:557-68.

43. Nabi J, Cone EB, Vasavada A, et al. Mobile health app for prostate cancer patients on androgen deprivation therapy: qualitative usability study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2020;8:e20224.

44. Li X, Zhang Y, Tian Y, Cheng Q, Gao Y, Gao M. Exercise interventions for older people with cognitive frailty-a scoping review. BMC Geriatr. 2022;22:721.

45. Ussing A, Mikkelsen MK, Villumsen BR, et al. Supervised exercise therapy compared with no exercise therapy to reverse debilitating effects of androgen deprivation therapy in patients with prostate cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2022;25:491-506.

46. Kempin S, Buchner A, Brose SF, et al. The effect of resistance and/or aerobic training on quality of life, fitness, and body composition in prostate cancer patients-a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancers. 2024;16:4286.

47. Fang YY, Lee YH, Chan JC, et al. Effects of exercise interventions on social and cognitive functioning of men with prostate cancer: a meta-analysis. Support Care Cancer. 2020;28:2043-57.

48. Toohey K, Hunter M, Paterson C, Mortazavi R, Singh B. Exercise adherence in men with prostate cancer undergoing androgen deprivation therapy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancers. 2022;14:2452.

49. Peng J, Chang R, Wei X, Yin Z, Liu Q. Effect of non-pharmacological interventions in people with cognitive frailty: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. BMC Public Health. 2024;24:2684.

50. Baguley BJ, Skinner TL, Jenkins DG, Wright ORL. Mediterranean-style dietary pattern improves cancer-related fatigue and quality of life in men with prostate cancer treated with androgen deprivation therapy: a pilot randomised control trial. Clin Nutr. 2021;40:245-54.

51. Dalla Via J, Owen PJ, Daly RM, et al. Musculoskeletal responses to exercise plus nutrition in men with prostate cancer on androgen deprivation: a 12-month RCT. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2021;53:2054-65.

52. Wilson RL, Taaffe DR, Newton RU, Hart NH, Lyons-Wall P, Galvão DA. Using exercise and nutrition to alter fat and lean mass in men with prostate cancer receiving androgen deprivation therapy: a narrative review. Nutrients. 2021;13:1664.

53. Vaiana AM, Asher AM, Tapia K, Morilak DA. Vortioxetine reverses impairment of visuospatial memory and cognitive flexibility induced by degarelix as a model of androgen deprivation therapy in rats. Neuroendocrinology. 2024;114:279-90.

Cite This Article

How to Cite

Download Citation

Export Citation File:

Type of Import

Tips on Downloading Citation

Citation Manager File Format

Type of Import

Direct Import: When the Direct Import option is selected (the default state), a dialogue box will give you the option to Save or Open the downloaded citation data. Choosing Open will either launch your citation manager or give you a choice of applications with which to use the metadata. The Save option saves the file locally for later use.

Indirect Import: When the Indirect Import option is selected, the metadata is displayed and may be copied and pasted as needed.

About This Article

Copyright

Data & Comments

Data

Comments

Comments must be written in English. Spam, offensive content, impersonation, and private information will not be permitted. If any comment is reported and identified as inappropriate content by OAE staff, the comment will be removed without notice. If you have any queries or need any help, please contact us at support@oaepublish.com.