Hiatal hernia repair in the era of robotic surgery: lessons learned from a single-center experience

Abstract

Aim: Robotic-assisted surgery has been successfully introduced in hiatal hernia repair; however, clear advantages over laparoscopy remain limited, with small series and contradictory results. This study aims to evaluate the outcomes of robotic hiatal hernia repair in non-selected patients.

Methods: All patients presenting with symptomatic hiatal hernia were included. The DaVinci® robotic platform was used, and a strict standardized operative technique was performed. Preoperative and postoperative data were prospectively collected and retrospectively analyzed.

Results: A total of 103 consecutive, unselected patients underwent surgery. Median total operating time was 72 min [range 46-168 min]. The 30-day complication rate was 12% (12/103). After a median follow-up of 29 months [range 1-64 months], the late complication rate was 5% and the recurrence rate was 5%.

Conclusion: Robotic surgery is a valuable option for hiatal hernia repair, especially in difficult cases or emergency operations. Whether this translates to better long-term outcomes needs to be further investigated in series with longer follow-up.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

Laparoscopic surgery is considered as the standard approach for hiatal hernia repair[1]. However, it remains challenging in some situations, due to problematic exposure in narrow spaces near vital structures, the need for nerve-sparing dissection, handling of fragile tissues (especially in emergency situations) and difficult suture skills. This results in a high rate of conversion to open surgery, early complications, late failures, and an associated learning curve, particularly during the initial stages[2,3]. Despite this, laparoscopic surgery is considered safe and has better short- and long-term outcomes compared to open surgery[4,5]. Robotic-assisted surgery has been successfully introduced into clinical routine during the past ten years, claiming to overcome the aforementioned challenges of hiatal hernia repair[6,7]. This superiority, compared with laparoscopy, is likely due to more stable visualization, better retraction capabilities, and the versatility of the articulated instruments, which allow precise angling at the instrument tip - a point particularly important during suturing tasks. However, it remains unclear whether this translates into true clinical benefits, as the existing literature comprises limited studies with sometimes contradictory results[8,9].

Robotic approach has shown superiority in terms of conversion rate to open surgery[6], occurrence of severe complications and even better quality of life outcomes in some reports[10]. A lower rate of recurrence has also been demonstrated in several series. These individual results are, however, challenged in a larger meta-analysis[11]. On the other hand, higher costs[10] and longer operating time have been highlighted in most of the reported experiences[11,12]. As is often the case in robotic surgical research, most series involve highly selected patients and surgeons with extensive skill and experience. As a result, the actual guidelines of the Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons (SAGES), one of the leading societies in this field, claim that the robotic approach is a valuable option but cannot be recommended systematically[1]. In our view, the true advantage of this high-end platform should be evaluated in clinical scenarios where laparoscopy reaches the limits of its capabilities, rather than in highly selected, straightforward cases.

The aim of this study was then to evaluate the short- and long-term outcomes of robotic hiatal hernia repair in non-selected and consecutive patients, including emergency surgery.

PATIENTS & METHODS

Since May 2012, our institution has implemented a multidisciplinary robotic surgery program - including digestive surgery, urology, and gynecology - using the DaVinci® system (Intuitive Surgical Inc., Sunnyvale, USA), transitioning from the Si model to the Xi model in 2017. From 2012, a mean of 407 procedures/year were performed in the institutions. The digestive surgery team comprised six experienced consultant surgeons, three of whom - including both authors - specialized in Upper GastroIntestinal (upper-GI) surgery. No teaching interventions were performed. We started the program with colorectal and bariatric surgery on a weekly basis. After accumulating approximately 500 bariatric surgery cases, hiatal hernia repairs have been performed systematically with the robot since February 2020, and laparoscopy was abandoned, even in emergency cases.

All patients underwent an extensive preoperative work-up, including upper endoscopy, Gastrografin esogastric series, and high-resolution manometry. Thoraco-abdominal computed tomography (CT) scanning was performed for hernias > 8 cm to assess esophageal length, and pH-impedance testing was performed in patients with non-erosive reflux symptoms. Hernia size was defined as the maximal transverse diameter of the sac (cm), measured on contrast series or CT scan. The preoperative work-up was reviewed in a multidisciplinary digestive board, and the decision to operate was made after discussion. Pertinent demographic, perioperative, and postoperative variables, as well as long-term follow-up data, were prospectively collected. All patients provided written consent for both the intervention and data collection, which were supervised by Clinique La Source, Lausanne, Switzerland. According to the institution’s regulations, this type of retrospective observational study did not require ethical approval.

Operative technique

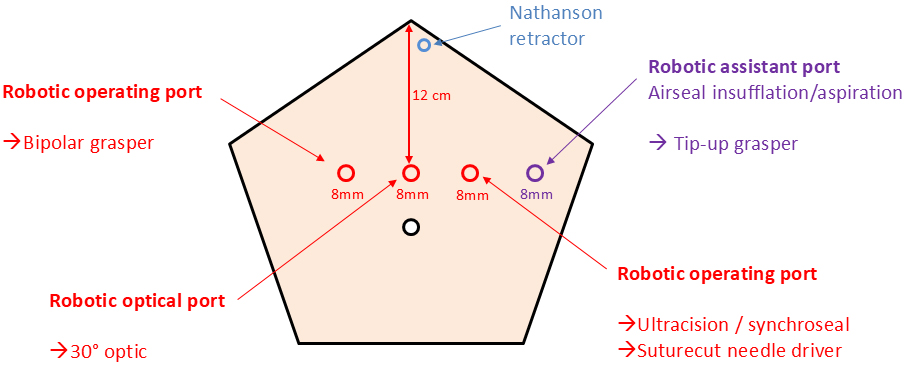

Patients were placed in the anti-Trendelenburg position with arms apart. After sterile draping, pneumoperitoneum was established using a Veress needle and a “water drop test.” A pressure of 12 mmHg was used at the start of the procedure and reduced to 9 mmHg after full installation, maintained with an AirSeal® insufflator (ConMed Inc., Florida, USA). Four 8 mm DaVinci ports were placed in a horizontal line, 12 cm below the xiphoid process [Figure 1]; no additional assistant port was used. AirSeal® valves dedicated to DaVinci trocars were employed. Under direct vision, a Nathanson retractor was placed to retract the left liver lobe and secured to the table with a locking arm. The robot was deployed in the “upper abdomen” setting, positioned on the patient’s right side, and docked in place. A standardized instrument set was used, including bipolar forceps (operating arm No. 2), Tip-up forceps (assistant arm), DaVinci irrigation/suction device (assistant arm), and suture-cut needle driver (operating arm No. 1). The main dissecting tool was a robotic Ultracision® for the first 65 cases and a SynchroSeal® fusion device for the last 38 cases, both placed in operating arm No. 1.

A standardized operative technique was applied in all patients, following this sequence: (1) dissection of the hiatus up to the lower pulmonary veins; (2) reintegration of the stomach into the abdominal cavity; (3) sac resection; (4) mobilization of the lesser curvature up to the second short gastric vessel; (5) closure of the hiatus with two running non-absorbable barbed sutures (V-Lock® 3.0) posteriorly and anteriorly; and (6) creation of a 180° posterior Toupet valve, secured on both sides of the esophagus with non-absorbable barbed sutures (V-Lock® 3.0) and fixed to the diaphragm with non-absorbable braided sutures. A 42 Fr (French gauge) calibrating tube was used in every patient.

Mesh repairs were performed in highly selected patients when tissue quality prevented a tension-free hiatus closure. If the gap was small and the diaphragmatic pillars could be reapproximated under tension, an absorbable Phasix® round-shaped mesh was placed around the esophagus and secured with absorbable interrupted sutures. For gaps too large to allow pillar reapproximation, a technique using a displaced Progrip® polyester mesh combined with a diaphragmatic relaxing counter-incision was employed, as described by Demeester et al. in 2013. A Collis gastroplasty was performed if, after full mobilization, the gastroesophageal junction could not be positioned intra-abdominally without traction, due to a short esophagus[13].

Study design & statistics

This study was a retrospective analysis of a prospectively maintained database, including all patients consecutively operated on with the robotic system at a single institution. The primary endpoint was the 30-day complication rate, classified according to the Clavien-Dindo system. Secondary endpoints included mortality, operative time, conversion to open or laparoscopic surgery, length of hospital stay, late complications (defined as gas bloat syndrome, late dysphagia, gastroparesis, or any other symptom requiring reoperation ≥ 3 months postoperatively), and recurrence rate (assessed by clinical examination with selective radiological work-up).

Physical follow-up was performed at 2 weeks, 2 months, 6 months, and 1 year postoperatively. After 1 year, follow-up was maintained via email or phone contact for 5 years.

Data were analyzed using Stata software (version 13.0; StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA). Categorical data are presented as percentages, and continuous data as median (range). As this was purely descriptive, no further statistical analysis was performed.

RESULTS

From February 2020 to June 2025, 103 patients were operated on for sliding hernia (91 cases), paraesophageal hernia (9 cases), and post-esophagectomy diaphragmatic hernia (3 cases). The median hernia size was 6 cm. Three patients (3%) underwent emergency surgery: two for acute post-esophagectomy hernia and one for gastric volvulus. Demographic and preoperative data are presented in Table 1.

Patient demographics and preoperative data

| Total | N = 103 |

| Hernia type (n, %) Type I (sliding) Type II, III, IV (paraesophageal) Post-oesophagectomy | 91 (88%) 9 (9%) 3 (3%) |

| Hernia size (median [range] | 6 cm [range 4-16] |

| Symptoms (n, %) Reflux disease Dysphagia Extra-digestive (ENT, pulmonary) | 76 (74%) 54 (52%) 22 (21%) |

| Age, years (median [range]) | 57 [25-84] |

| BMI (median [range]) | 24 kg/m2 [19-32] |

| ASA score (%) 1 2 3 4 | 36% 53% 11% 0% |

| Surgical anteriority (n, %) Primary repair Redo operation 1st Redo operation 2nd | 79 (77%) 21 (20%) 3 (3%) |

Perioperative data are presented in Table 2. Median total operating time was 72 min, median console time was 70 min, and median docking time was 3 min. A mesh was used in 5 patients (5%: 2 with Phasix® ST mesh and 3 with Progrip® mesh plus relaxing incision). Collis gastroplasty was performed in 4 patients (4%).

Perioperative data

| Total | N = 103 |

| Operative time (median [range]) Total OR time Docking time Robotic time | 72 min [46-168] 3 min [2-6] 70 min [43-163] |

| Mesh placement (n, %) Phasix® ST Progrip® + Relaxing incision | 2 (2%) 3 (3%) |

| Collis gastroplasty (n, %) | 4 (4%) |

Postoperative outcomes (early and late) are presented in Table 3. The 30-day complication rate was 12%, with no severe complications (Clavien-Dindo Grade III or higher). Regarding other secondary endpoints, there were no conversions to open or laparoscopic surgery, and the median length of hospital stay was 2 days. After a median follow-up of 29 months, the late complication rate was 5%, and the recurrence rate was 5%.

Postoperative outcomes

| Total | N = 103 |

| 30-day complications, type (n, %) Total complications Peripheral phlebitis Pneumonia Atelectasis Pulmonary embolism Surgical site infection (incisions) | 12 (12%) 2 (2%) 3 (3%) 2 (2%) 1 (1%) 2 (2%) 2 (2%) |

| 30-day complications, classification (n, %) * Grade I Grade II Grade III Grade IV Grade V | 2 (2%) 10 (10%) 0 0 0 |

| Length of Hospital stay (median [range]) | 2 days [2-12] |

| Follow-up (median [range]) | 29 months [1-64] |

| Late complications, type (n, %) Total complications Gas bloat syndrome Gastroparesis Late dysphagia | 5 (5%) 2 (2%) 2 (2%) 1 (1%) |

| Recurrence (n, %) | 5 (5%) |

| Recurrence timing and symptoms 6 months (Dysphagia) 8 months (Recurrent reflux) 11 months (Recurrent reflux) 14 months (Recurrent reflux) 36 months (Dysphagia) |

DISCUSSION

This retrospective cohort study suggests that robotic surgery for hiatal hernia repair is a valuable approach, achieving both early and late outcomes comparable to laparoscopic surgery, even in unselected patients or emergency interventions.

Longer operating time of robotic interventions has frequently been highlighted in the past[11,12], when compared to laparoscopy. However, several recent studies did not confirm such disadvantages. O’connor et al. reported similar results (175 vs. 179 min, P = 0.68) in a series of 114 robotic patients[13]. A large meta-analysis of 10 studies, including an impressive 186,259 patients and published by Elissavet et al. in 2023, confirms the absence of a statistical difference (t = 1.41, df = 5; 95% CI, -0.15 to 0.52; P = 0.22), compared to laparoscopy[10]. Unfortunately, all the studies included in this meta-analysis were retrospective and none of them were randomized, limiting the power of their conclusion. Our experience is objectively similar, resulting in a very short median operating time (72 min). This is completely comparable to the mean operating time in Europe in 2024 (96 min), data provided by Intuitive Surgical, based on the report of all the machines installed on the continent. This good result may be explained by different local factors. First of all, our surgical team was experienced in both robotics and upper GI surgery. There were no teaching interventions. Moreover, the operating room (OR) setting was optimal, as a fully dedicated scrub-nurse team had been built over the years (resulting in short docking time and fast instrument-exchange time). We also had a fair experience in bariatric robotic surgery before starting our hiatal hernia program and the first five cases were done with a proctor provided by Intuitive, resulting in an absence of a learning curve in our case. This positive effect of proctorship programs has been demonstrated by Straatman et al. in a recent study, concluding that such organized learning pathways may shorten learning curves, ensuring patient safety, preventing adverse outcomes, and accelerating adoption and integration of robotic surgery[14].

Our perioperative complication rate was 12%, as presented in Table 2. We had no severe complications (Clavien-Dindo III or higher) and no reoperation. This was equivalent to those reported in the literature, ranging from 5 to 15%[10,11,15-17]. The type of early complications that we encountered is also comparable to those most frequently reported in the literature, as described in the large meta-analysis by Elissavet et al.[10], including dysphagia, pleural effusion, pneumonia, venous thromboembolism, cardiac failure, atrial fibrillation, atelectasis, delayed gastric emptying, wound infections, thoracic or abdominal infections, and mediastinitis. When compared to laparoscopy, the early complication rate varies greatly, depending on the cohorts studied and contradictory conclusions were reported. Some single-center series suggest a benefit, while large national databases show an increased risk in robotics, possibly linked to the learning curve and case selection.

Minimally invasive approaches have invariably been associated with a shorter length of hospital stay in surgery. This effect is also observed in the present setting. Soliman et al. reported shorter stay for robotic hernia repair (1.9 vs. 2.5 days, P < 0,01)[16]. Similar results were observed by Gerull et al. (1.8 days vs. 3.1 days; P < 0.001)[17]. These findings were very similar to ours (2 days, range 2-12). This outcome may, however, be influenced by local policies, introducing bias. In our experience, several patients could have been discharged the day after the operation, or even on the same day for very selected cases, as also reported by other teams. However, the reimbursement system (DRG, Diagnosis-Related Groups) in Switzerland strongly discourages early discharge, as a minimum stay of two days is required for full cost coverage after hiatal hernia repair (data from SwissDRG, https://www.swissdrg.org/fr/somatique-aigue/systeme-swissdrg-1402025/regles-et-definitions). We assume that similar situations have been encountered by other teams, without systematic reporting, inducing a clear bias on this particular topic. Finally, scrutinizing the literature, a step back is necessary, as statistically significant results are not always clinically relevant; many teams reported rather small absolute differences (sometimes fractions of a day) in length of stay, despite very small P-values.

Late outcomes are of primary importance when introducing a new approach in surgery, especially for functional pathologies, where error margin is critical. From this point of view, our late complication rate (5%) and recurrence rate (5%) seem promising, despite a median follow-up limited to 29 months. Only twenty of our patients reached the long-term follow-up of 5 years. This limitation is unfortunately frequent in the literature also[10,12,16]. If no differences were often observed with the robotic approach regarding late complications, the quality of the studies (mainly retrospective) and the inconsistency in both complication definitions and screening limit the strength of the conclusions. Better visualization, more versatile instrument movements, and enhanced precision for suturing have all been claimed as clear advantages of robotic surgery, potentially improving the quality of repair and translating into a lower recurrence rate. An effective reduction of this outcome has been reported recently by O’Connor et al. (13.3% vs. 32.8%, P = 0,008), but the short periods of follow-up (1 year only) clearly challenge these enthusiastic results[15]. Soliman et al. also reported lower complication rates (6.3% vs. 19.2%, P = 0.001) in a series of 142 patients[16]. Several other series have at least reported similar results for robotic surgery, for longer periods of surveillance. On the other hand, Klock et al. described in their nationwide database higher overall complication rates for robotic surgery (9.2% vs. 6.8%, odds ratio [OR]: 1.4, 95% CI: 1.3-1.5, P < .001), but a trend was observed, toward similar complication rates across years. This effect was correlated with the annual procedural volume increase[18].

After almost 10 years of laparoscopic practice, our transition to robotic hiatal hernia repair subjectively improved our technique through enhanced visualization, increased dexterity, and better ergonomics. Our impression was that the procedure was enhanced mainly during the mediastinal and posterior dissection, due to improved exposure provided by the wristed instruments (particularly the tip-up grasper). Suturing tasks may also be simplified, especially for laparoscopic surgeons at the beginning of the learning curve. This was particularly true in difficult cases, such as hiatal hernias larger than 10 cm (25 cases, 24% of the cohort), redo operations (23% of our cohort, including 3 patients with more than two previous interventions), post-esophagectomy hernias (3 patients), and emergency surgery (3 patients), where laparoscopic approaches would have been clearly challenging. As our study had no control group, this aspect remains subjective but may be supported by our low early complication rate and relatively short operating time. Several comparative studies have included so-called “advanced cases”, but no clear conclusions can be drawn, as most were not specifically designed for this endpoint[15,16,19,20]. For example, in the study by Soliman et al., 70% of the cases involved repair of either type III or type IV hiatal hernias, a rate higher than in our cohort[16].

Another challenge for robotics is cost efficiency. This issue has long been raised across nearly all surgical fields, often based on early experiences and immature programs. In most reports, the cost difference was statistically significant - unfavorable to the robotic approach - although the absolute difference was sometimes small (1,500 to 2,500 USD)[21]. However, some reports showed similar costs between the two approaches[22]. Numbers may drastically change as teams improve their experience, decrease operative time, and refine the use of costly instruments. Moreover, institutional costs vary greatly between countries and types of institutions. Finally, the pricing of both robots and instruments varies over time, slowly decreasing with increased competition between companies, which has only been effective for one or two years. In our opinion, all these arguments have led to biased conclusions, assigned to a young and evolving technology. In our institution and local setting (instrument pricing, reimbursement, cost of personnel), there were no significant additional costs for robotics, provided that machine use was optimized in terms of OR occupation (more than 400 cases/year). Finally, a distinction between costs and institutional profitability should be made, as they may be very different. Such analysis has been done by Lekarczyk et al.[22], concluding that despite higher supply costs and charges, hospital profits were similar. Institutions should therefore handle their own analysis to understand the real economic effect of such a new implementation. Another important aspect is the marketing effect of “having a robot” in an institution, in a setting of strong competition between centers. Although it should definitely not drive such a program, institutions cannot overlook this effect. This is particularly true in urology in Europe, where laparoscopic or open approaches for radical prostatectomy have almost disappeared and where centralization has been driven by patients toward centers offering robotic resection. This could ultimately influence the hospital’s income in the future by increasing the case load, but also by improving productivity itself, as discussed in the analysis by Horn et al. in the Journal of Health Economics in 2022[23].

Several limitations must be highlighted in the current study. Because we chose to optimize robotic use for cost-efficiency, we completely abandoned classic laparoscopy; therefore, we could not design a comparative study between the two techniques. We also emphasize that all cases were performed by well-trained surgeons in both robotics and upper GI surgery, which may limit the generalizability of our results to early-stage clinical settings. However, the proctoring system offered by the industry should help overcome this difficulty, as previously explained. On the other hand, we chose to include all our cases, including challenging ones, as noted above. In our opinion, this reflects the versatility of robotic surgery in real clinical practice.

The design of our follow-up after one year (email or phone call) could also be criticized. According to our local policy, we would not reoperate on an asymptomatic patient. Therefore, we limited follow-up to a clinical evaluation, providing additional examinations (radiology or endoscopy) only if dysphagia or recurrent reflux was reported. As a result, the true recurrence rate may have been underestimated. However, exposing patients to the risks of unnecessary examinations (that would not change the clinical pathway) seems unethical to us.

In conclusion, the results of this cohort study suggest that robotic surgery is a valuable option for hiatal hernia repair, especially in complex cases. Whether this translates into better long-term outcomes needs to be further investigated in series with longer follow-up.

DECLARATIONS

Authors’ contributions

Made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the study, critical manuscript review and corrections, and study interpretation: Pierre A, Jean-Marie C

Performed data acquisition, as well as technical and material support: Pierre A

Availability of data and materials

All data and materials used in this study, including the anonymized dataset, are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Financial support and sponsorship

None.

Conflicts of interest

All authors declared that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

This study is a purely observational retrospective study with no additional procedures or changes to the clinical protocol. According to the regulations of Clinique La Source, ethical approval was not required. All patients provided written informed consent for the intervention and data collection.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026.

REFERENCES

1. Daly S, Kumar SS, Collings AT, et al. SAGES guidelines for the surgical treatment of hiatal hernias. Surg Endosc. 2024;38:4765-75.

2. Leeder PC, Smith G, Dehn TC. Laparoscopic management of large paraesophageal hiatal hernia. Surg Endosc. 2003;17:1372-5.

3. Okrainec A, Ferri LE, Feldman LS, Fried GM. Defining the learning curve in laparoscopic paraesophageal hernia repair: a CUSUM analysis. Surg Endosc. 2011;25:1083-7.

4. Fullum TM, Oyetunji TA, Ortega G, et al. Open versus laparoscopic hiatal hernia repair. JSLS. 2013;17:23-9.

5. Zehetner J, Demeester SR, Ayazi S, et al. Laparoscopic versus open repair of paraesophageal hernia: the second decade. J Am Coll Surg. 2011;212:813-20.

6. Tolboom RC, Broeders IA, Draaisma WA. Robot-assisted laparoscopic hiatal hernia and antireflux surgery. J Surg Oncol. 2015;112:266-70.

7. Brenkman HJ, Parry K, van Hillegersberg R, Ruurda JP. Robot-assisted laparoscopic hiatal hernia repair: promising anatomical and functional results. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2016;26:465-9.

8. Ma L, Luo H, Kou S, et al. Robotic versus laparoscopic surgery for hiatal hernia repair: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis. J Robot Surg. 2023;17:1879-90.

9. Karikis I, Pachos N, Mela E, et al. Comparative analysis of robotic and laparoscopic techniques in hiatal hernia and crural repair: a review of current evidence and outcomes. Hernia. 2024;28:1559-69.

10. Elissavet S, Ioannis G, Panagiotis P, Konstantinos M, Apostolos K. Robotic-assisted versus laparoscopic paraesophageal hernia repair: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Minim Invasive Surg. 2023;26:134-45.

11. Bhatt H, Wei B. Comparison of laparoscopic vs. robotic paraesophageal hernia repair: a systematic review. J Thorac Dis. 2023;15:1494-502.

12. Giovannetti A, Craigg D, Castro M, Ross S, Sucandy I, Rosemurgy A. Laparoendoscopic single-site (LESS) versus robotic “Redo” hiatal hernia repair with fundoplication: which approach is better? Am Surg. 2019;85:978-84.

13. Greene CL, DeMeester SR, Zehetner J, Worrell SG, Oh DS, Hagen JA. Diaphragmatic relaxing incisions during laparoscopic paraesophageal hernia repair. Surg Endosc. 2013;27:4532-8.

14. Straatman J, Rahman SA, Carter NC, et al. Proctored adoption of robotic hiatus hernia surgery: outcomes and learning curves in a high-volume UK centre. Surg Endosc. 2023;37:7608-15.

15. O’Connor SC, Mallard M, Desai SS, et al. Robotic versus laparoscopic approach to hiatal hernia repair: results after 7 years of robotic experience. Am Surg. 2020;86:1083-7.

16. Soliman BG, Nguyen DT, Chan EY, et al. Robot-assisted hiatal hernia repair demonstrates favorable short-term outcomes compared to laparoscopic hiatal hernia repair. Surg Endosc. 2020;34:2495-502.

17. Gerull WD, Cho D, Arefanian S, Kushner BS, Awad MM. Favorable peri-operative outcomes observed in paraesophageal hernia repair with robotic approach. Surg Endosc. 2021;35:3085-9.

18. Klock JA, Walters RW, Nandipati KC. Robotic hiatal hernia repair associated with higher morbidity and readmission rates compared to laparoscopic repair: 10-year analysis from the national readmissions database (NRD). J Gastrointest Surg. 2023;27:489-97.

19. Anyomih TTK, Mehta A, Sackey D, et al. Robotic versus laparoscopic general surgery in the emergency setting: a systematic review. J Robot Surg. 2024;18:281.

20. Rodier S, Henning J, Kukreja J, Mohammedi T, Shah P, Damani T. Robotic primary and revisional hiatal hernia repair is safe and associated with favorable perioperative outcomes: a single institution experience. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2023;33:932-6.

21. Gonçalves-Costa D, Barbosa JP, Quesado R, Lopes V, Barbosa J. Robotic surgery versus Laparoscopic surgery for anti-reflux and hiatal hernia surgery: a short-term outcomes and cost systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Langenbeck's Arch Surg. 2024;409:175.

22. Lekarczyk A, Sinha H, Dvir D, Goyert J, Airhart A, Reddy RM. Similar hospital profits with robotic-assisted paraesophageal hiatal hernia repair, despite higher or supply costs. Surg Endosc. 2023;37:3952-5.

Cite This Article

How to Cite

Download Citation

Export Citation File:

Type of Import

Tips on Downloading Citation

Citation Manager File Format

Type of Import

Direct Import: When the Direct Import option is selected (the default state), a dialogue box will give you the option to Save or Open the downloaded citation data. Choosing Open will either launch your citation manager or give you a choice of applications with which to use the metadata. The Save option saves the file locally for later use.

Indirect Import: When the Indirect Import option is selected, the metadata is displayed and may be copied and pasted as needed.

About This Article

Special Topic

Copyright

Data & Comments

Data

Comments

Comments must be written in English. Spam, offensive content, impersonation, and private information will not be permitted. If any comment is reported and identified as inappropriate content by OAE staff, the comment will be removed without notice. If you have any queries or need any help, please contact us at support@oaepublish.com.